Abstract

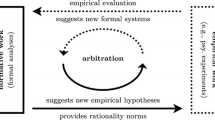

This position paper advocates combining formal epistemology and the new paradigm psychology of reasoning in the studies of conditionals and reasoning with uncertainty. The new paradigm psychology of reasoning is characterized by the use of probability theory as a rationality framework instead of classical logic, used by more traditional approaches to the psychology of reasoning. This paper presents a new interdisciplinary research program which involves both formal and experimental work. To illustrate the program, the paper discusses recent work on the paradoxes of the material conditional, nonmonotonic reasoning, and Adams’ Thesis. It also identifies the issue of updating on conditionals as an area which seems to call for a combined formal and empirical approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Thus, we do not accept Kauppinen’s negative experimentalism thesis—which allegedly is accepted by some experimental philosophers—according to which “armchair reflection and informal dialogue are not reliable sources of evidence for (philosophically relevant) claims about folk concepts” (Kauppinen 2007, p. 97).

As an anonymous referee noted, the logical empiricists may have believed their verification theory of meaning, according to which a sentence is meaningful only if it is verifiable, to eliminate the possibility that philosophers were really writing fiction. But that theory was soon found to be untenable, if only because it does not live up to its own standards of meaningfulness.

Callebaut (1993) gives an excellent overview of the naturalization program in philosophy up to the 1980s.

Specifically, a bit more than half of the participants interpret the conditional as a conditional probability and a sizable proportion of participants interpret it as a conjunction in the beginning of these experiments. This replicates a robust finding in traditional probabilistic truth table tasks (Evans et al. 2003; Oberauer and Wilhelm 2003). However, in the end of the experiment, more than 80 % of the responses were consistent with the conditional probability interpretation. In these tasks inter-individual differences do not imply different reasoning/interpretation strategies but rather reflect how fast participants are able to adopt the competence interpretation. Although we doubt that the iterative presentation of the same task will resolve all aspects related to the deep problem of individual differences, we believe that it helps resolve at least some of them.

An example of the latter kind is the distinction between reasoning to an interpretation and reasoning from an interpretation, where the former involves interpreting the meaning of the task material, while the latter begins only after the interpretation of the task material has been fixed by the participant and he or she starts to solve the task. We like to think that it is not coincidental that this distinction is due to recent joint work by a psychologist (or at least cognitive scientist) and a philosopher, to wit, Keith Stenning and Michiel van Lambalgen (Stenning and van Lambalgen 2008).

For more on what formal epistemology is and how it differs from mainstream epistemology as well as from the probabilist underground epistemology that van Fraassen refers to, see (Douven 2013c).

For an overview, see Bennett (2003).

“All” here includes the special case where Pr(B) = 1. Bonnefon and Politzer correctly point out that in this case “ ‘If x, y’ must also be certain, and the inference is valid” (Bonnefon and Politzer 2011, p. 154). This is true for the standard approach to probability, which defines the conditional probability Pr(B | A) by the fraction of the joint and the marginal probability, Pr(A ∧ B) / Pr(A) (provided Pr(A) > 0, otherwise Pr(B | A) is undefined). In the framework of coherence-based probability theory, however, Pr(B | A) is not necessarily certain if Pr(B) = 1. As Pr(A) may be equal to 0, it follows that Pr(B | A) may also be equal to 0, and therefore 0 ≤ Pr(B | A) ≤ 1 is coherent (Pfeifer 2013a).

An anonymous referee noted that it is not clear whether the observed response—that nothing follows—fully accounts for a “subjective feeling of oddity”, which emerges from some instantiations of the paradoxes of the material conditional. The tasks used in Pfeifer and Kleiter (2011) were formulated by neutral instantiations of A and B (i.e., in terms of colors and figures), which means that a feeling of oddity—if it occurred—was based on the formal structure of the paradoxes only.

An argument form is probabilistically non-informative iff the tightest coherent probability bounds on the conclusion are zero and one, respectively, under all possible probability values of the premises (Pfeifer and Kleiter 2009).

We observe that this argument form is a special case of the cautious monotonicity rule of System P. (Compare the probability propagation rules in Gilio (2002)).

From “If A, then B” and “If B, then C” infer “If A, then C”.

This argument form corresponds to the cut rule of System P (Gilio 2002). Moreover, it can be interpreted as a conditional version of modus ponens: each premise and the conclusion conditionalize on A, if A is dropped, the modus ponens remains.

If conditionals do not express propositions, they cannot occur in ordinary conjunctions. They can occur in what Adams calls “quasi-conjunctions” (Adams 1975, p. 46 f). By Adams’ own admission, however, quasi-conjunctions lack some important logical features of conjunctions.

Note that, in view of the experiments on the probabilities of conditionals mentioned in the text, Douven and Verbrugge’s results also show that the probability of a conditional is not the same as the degree of acceptability of a conditional, pace Adams.

An anonymous referee noticed that the fact that we seem to learn something in such cases puts pressure on Adams’ non-propositional view of conditionals. We agree, albeit only insofar as Adams’ view rules out the seemingly most straightforward type of proposal for modelling conditional updates, to wit, those proposals that model such updates as the accommodation, in some way, of the proposition (putatively) expressed by the conditional. But there are other forms that updating on a conditional might take; see Douven and Romeijn (2011) and Douven (2012).

For an important different approach to modelling updates on conditionals, see Hartmann and Rafiee Rad (2012).

References

Adams, E.W. 1965. The logic of conditionals. Inquiry 8: 166–197.

Adams, E.W.1975. The logic of conditionals. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Antoniou, G. 1997. Nonmonotonic reasoning. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Benferhat, S., Bonnefon, J.-F., and R. Da Silva Neves, 2005. An overview of possibilistic handling of default reasoning, with experimental studies. Synthese 146: 53–70.

Benferhat, S., D. Dubois, and H. Prade. 1997. Nonmonotonic reasoning, conditional objects and possibility theory. Artificial Intelligence 92: 259–276.

Bennett, J. 2003. A philosophical guide to conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bonnefon, J.-F., and G. Politzer. 2011. Pragmatics, mental models and one paradox of the material conditional. Mind & Language 26: 141–155.

Boutilier, C., and M. Goldszmidt 1995. On the revision of conditional belief sets. In Conditionals. From philosophy to computer science, eds. G. Crocco, L. Fariñas del Cerro, A. Herzig, 267–300, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bovens, L., and S. Hartmann. 2003. Bayesian epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Braine, M.D.S., and D.P. O’Brien. eds. 1998. Mental logic. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Brewka, G. 1991. Nonmonotonic reasoning: Logical foundations of commonsense. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brewka, G., V.W. Marek, and M. Truszczyéski. 2011. Nonmonotonic reasoning. Essays celebrating its 30th anniversary, of studies in logic, vol. 31. London: College Publications.

Byrne, R.M.J. 1989. Suppressing valid inferences with conditionals. Cognition 31: 61–83.

Callebaut, W. 1993. Taking the naturalistic turn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chater, N., and M. Oaksford. 1999. The probability heuristics model of syllogistic reasoning. Cognitive Psychology 38: 191–258.

Cohen, S. 1988. How to be a fallibilist. Philosophical Perspectives 2: 91–123.

Cullen, S. 2010. Survey-driven romanticism. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 1: 275–296.

Da Silva Neves, R., J.-F. Bonnefon, and E. Raufaste. 2002. An empirical test of patterns for nonmonotonic inference. Annals of Mathematics and Artificial Intelligence 34: 107–130.

Dancygier, B. ed. 1998. Conditionals and predictions: Time, knowledge and causation in conditional constructions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Declerck, R., and S. Reed. 2001. Conditionals: A comprehensive empirical analysis. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

DeRose, K. 1992. Contextualism and knowledge attributions. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 52: 913–929.

Douven, I. 2008. The evidential support theory of conditionals. Synthese 164: 19–44.

Douven, I. 2011. Abduction. In The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, ed. E.N. Zalta. Spring.

Douven, I. 2012. Learning conditional information. Mind & Language 27: 239–263.

Douven, I. 2013a. The epistemology of conditionals. Oxford Studies in Epistemology 4: 3–33.

Douven, I. 2013b. Inference to the best explanation, Dutch books, and inaccuracy minimisation. Philosophical Quarterly 63: 428–444.

Douven, I. 2013c. Formal epistemology. In Oxford handbooks online in philosophy, ed. S. Goldberg. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Forthcoming.

Douven, I., and R. Dietz. 2011. A puzzle about Stalnaker’s hypothesis. Topoi 30: 31–37.

Douven, I., and W. Meijs. 2007. Measuring coherence. Synthese 156: 405–425.

Douven, I., and J.-W. Romeijn. 2011. A new resolution of the Judy Benjamin problem. Mind 120: 637–670.

Douven, I., and S. Verbrugge. 2010. The Adams family. Cognition 11: 302–318.

Douven, I., and S. Verbrugge. 2013. The probabilities of conditionals revisited. Cognitive Science 37: 711–730.

Earman, J. 1992. Bayes or bust? A critical examination of Bayesian confirmation theory. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Edgington, D. 2003. What if? Questions about conditionals. Mind & Language 18: 380–401.

Evans, J.S.B.T. 2012. Questions and challenges to the new psychology of reasoning. Thinking & Reasoning 18: 5–31.

Evans, J.S.B.T., J.L. Allen, S. Newstead, and P. Pollard. 1994. Debiasing by instruction: The case of belief bias. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology 6: 263–285.

Evans, J.S.B.T., S.J. Handley, and D.E. Over. 2003. Conditionals and conditional probability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 29: 321–355.

Evans, J.S.B.T., and D.E. Over. 2004. If . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ford, M. 2004. System LS: A three-tiered nonmonotonic reasoning system. Computational Intelligence 20: 89–108.

Fugard, A.J.B., N. Pfeifer, and B. Mayerhofer. 2011a. Probabilistic theories of reasoning need pragmatics too: Modulating relevance in uncertain conditionals. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 2034–2042.

Fugard, A.J.B., N. Pfeifer, B. Mayerhofer, and G.D. Kleiter. 2011b. How people interpret conditionals: Shifts towards the conditional event. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 37: 635–648.

Gärdenfors, P. 1988. Knowledge in flux. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gendler, T.S. 2007. Philosophical thought experiments, intuitions, and cognitive equilibrium. Midwest Studies in Philosophy 31: 68–89.

Gilio, A. 2002. Probabilistic reasoning under coherence in System P. Annals of Mathematics and Artificial Intelligence 34: 5–34.

Grice, H.P.1975. Logic and conversation. In Syntax and semantics, Speech acts, vol. 3, eds. P. Cole, J.L. Morgan. New York: Seminar Press.

Hahn, U., and M. Oaksford. 2006. A Bayesian approach to informal argument fallacies. Synthese 152: 207–236.

Harris, A.J.L., and U. Hahn. 2009. Bayesian rationality in evaluating multiple testimonies: Incorporating the role of coherence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 35: 1366–1373.

Hartmann, S., and S. Rafiee Rad. 2012. Updating on conditionals = Kullback–Leibler + causal structure. Manuscript.

Hawthorne, J., and D. Makinson. 2007. The quantitative/qualitative watershed for rules of uncertain inference. Studia Logica 86: 247–297.

Howson, C., and P. Urbach. 2006. Scientific reasoning: The Bayesian approach, 3rd edn. Chicago: Open Court.

Jackson, F. ed. 1991. Conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jeffrey, R. 2004. Subjective probability: The real thing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson-Laird, P.N. 1983. Mental models: Towards a cognitive science of language, inference and consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson-Laird, P.N., and R.M.J. Byrne. 2002. Conditionals: A theory of meaning, pragmatics, and inference. Psychological Review 109: 646–678.

Kahneman, D., P. Slovic, and A. Tversky. eds. 1982. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kauppinen, A. 2007. The rise and fall of experimental philosophy. Philosophical Explorations 10: 95–118.

Kemp, C., N.D. Goodman, and J.B. Tenenbaum. 2010. Learning to learn causal models. Cognitive Science 34: 1185–1243.

Kern-Isberner, G. 1999. Postulates for conditional belief revision. In Proceedings of the 16th international joint conference on artificial intelligence, ed. T. Dean, 186–191. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

Koehler, D.J. 1991. Explanation, imagination, and confidence in judgment. Psychological Bulletin 110: 499–519.

Kraus, S., D. Lehmann, and M. Magidor. 1990. Nonmonotonic reasoning, preferential models and cumulative logics. Artificial Intelligence 44: 167–207.

Lewis, D. 1976. Probabilities of conditionals and conditional probabilities. Philosophical Review 85: 297–315.

Lindworsky, J. 1916. Das schlußfolgernde Denken. Experimentell-psychologische Untersuchungen. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herdersche Verlagshandlung.

Lipton, P. 2004. Inference to the best explanation, 2nd edn. London: Routledge.

Lombrozo, T. 2007. Simplicity and probability in causal explanation. Cognitive Psychology 55: 232–257.

May, J., W. Sinnott-Armstrong, J.G. Hull, and A. Zimmerman. 2010. Relevant alternatives, and knowledge attributions: An empirical study. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 1: 265–273.

McCarthy, J. 1977. Epistemological problems of artificial intelligence. In IJCAI’77: Proceedings of the 5th international joint conference on artificial intelligence, 1038–1044. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.

McGee, V. 1989. Conditional probabilities and compounds of conditionals. Philosophical Review 98: 485–541.

Oaksford, M., and N. Chater. 1991. Against logicist cognitive science. Mind & Language 6: 1–38.

Oaksford, M., and N. Chater. 1994. A rational analysis of the selection task as optimal data selection. Psychological Review 101: 608–631.

Oaksford, M., and N. Chater. 2007. Bayesian rationality: The probabilistic approach to human reasoning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oaksford, M., and N. Chater. 2009. Précis of Bayesian rationality: The probabilistic approach to human reasoning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 32: 69–120.

Oberauer, K., and O. Wilhelm. 2003. The meaning(s) of conditionals: Conditional probabilities, mental models and personal utilities. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 29: 680–693.

Over, D.E. 2009. New paradigm psychology of reasoning. Thinking and Reasoning 15: 431–438.

Over, D.E., I. Douven, and S. Verbrugge. 2013. Scope ambiguities and conditionals. Thinking and Reasoning. doi:10.1080/13546783.2013.810172.

Over, D.E., and J. St B.T. Evans. 2003. The probability of conditionals: The psychological evidence. Mind & Language 18: 340–358.

Over, D.E., C. Hadjichristidis, J. St B.T. Evans, S.J. Handley, and S. Sloman. 2007. The probability of causal conditionals. Cognitive Psychology 54: 62–97.

Pelletier, F.J., and R. Elio. 1997. What should default reasoning be, by default? Computational Intelligence 13: 165–187.

Pfeifer, N. 2012. Experiments on Aristotle’s thesis: Towards an experimental philosophy of conditionals. The Monist 95: 223–240.

Pfeifer, N. 2013a. Reasoning about uncertain conditionals. Studia Logica. In press. doi:10.1007/s11225-013-9505-4.

Pfeifer, N. 2013b. The new psychology of reasoning: A mental probability logical perspective. Thinking and Reasoning. In press doi:10.1080/13546783.2013.838189.

Pfeifer, N., and G.D. Kleiter 2003. Nonmonotonicity and human probabilistic reasoning. In Proceedings of the 6th workshop on uncertainty processing, 221–234. Hejnice. September 24–27th, 2003.

Pfeifer, N., and G.D. Kleiter. 2005. Coherence and nonmonotonicity in human reasoning. Synthese 146: 93–109.

Pfeifer, N., and G.D. Kleiter 2006. Is human reasoning about nonmonotonic conditionals probabilistically coherent? In: Proceedings of the 7th workshop on uncertainty processing, 138–150. Mikulov. September 16–20th, 2006.

Pfeifer, N., and G.D. Kleiter. 2009. Framing human inference by coherence based probability logic. Journal of Applied Logic 7: 206–217.

Pfeifer, N., and G.D. Kleiter 2010. The conditional in mental probability logic. In Cognition and conditionals: Probability and logic in human thought, eds. M. Oaksford, N. Chater, 153–173. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pfeifer, N., and G.D. Kleiter 2011. Uncertain deductive reasoning. In The science of reason: A Festschrift for Jonathan St. B.T. Evans, eds. K. Manktelow, D.E. Over, S. Elqayam, 145–166. Hove: Psychology Press.

Polanyi, M. 1976. The tacit dimension. New York: Anchor Books.

Politzer, G., and G. Bourmaud. 2002. Deductive reasoning from uncertain conditionals. British Journal of Psychology 93: 345–381.

Politzer, G. 2005. Uncertainty and the suppression of inferences. Thinking & Reasoning 11(1): 5–33.

Quine, W.VO. 1969. Epistemology naturalized. In Ontological relativity and other essays, ed. W.V.O. Quine, 69–90. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rips, L.J. 1994. The psychology of proof: Deductive reasoning in human thinking. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Schurz, G. 2005. Non-monotonic reasoning from an evolution-theoretic perspective: Ontic, logical and cognitive foundations. Synthese 146: 37–51.

Skyrms, B. 1980. Causal necessity. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sloman, S. 2005. Causal models: How people think about the world and its alternatives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stenning, K., and M. van Lambalgen. 2005. Semantic interpretation as computation in nonmonotonic logic: The real meaning of the suppression task. Cognitive Science 29: 919–960.

Stenning, K., and M. van Lambalgen. 2008. Human reasoning and cognitive science. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Störring, G. 1908. Experimentelle Untersuchungen zu einfachen Schlußprozessen. Archiv für die Gesamte Psychologie 11: 1–127.

van Fraassen, B.C. 1989. Laws and symmetry. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Waldmann, M., and Y. Hagmayer. 2005. Seeing versus doing: Two modes of accessing causal knowledge. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 31: 216–227.

Weisberg, J. 2009. Locating IBE in the Bayesian framework. Synthese 167: 125–143.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous reviewers and Paul Égré for useful comments. This work is supported by the FWF project P20209 and the DFG grant PF 740/2-1 (project leader: Niki Pfeifer; project within the DFG Priority Program SPP 1516 “New Frameworks of Rationality”). Niki Pfeifer is supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pfeifer, N., Douven, I. Formal Epistemology and the New Paradigm Psychology of Reasoning. Rev.Phil.Psych. 5, 199–221 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-013-0165-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-013-0165-0