Abstract

This paper develops and defends the view that substantively normative uses of words like “good”, “right” and “ought” (e.g. moral uses) are irresolvably indeterminate: any single case of application is like a borderline case for a vague or indeterminate term, in that the meaning-fixing facts (use, intentions, conventions, causal connections, reference magnets, etc.), together with the non-linguistic facts, fail to determine a truth-value for the target sentence in context. Normative claims, like vague or indeterminate borderline claims, are not meaningless, though. By making them, the speaker communicates information about the precisifications that s/he accepts. The analogy with vague/indeterminate language, I argue, lays out a new and interesting foundation for a subjectivist approach to normativity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See McGee and McLaughlin (1995) for this way of characterizing vagueness/indeterminacy. Here, and in what follows, I will assume that epistemicism—i.e. the view that vagueness and indeterminacy are a kind of ignorance—is false. Later on, I will spell out this assumption in more detail.

Throughout I will focus exclusively on thin normativity, i.e. the one associated with terms like “good”, “ought”, “is a reason for”, etc. Note that some authors use “normative” a bit more narrowly than this, perhaps in contrast with “evaluative”. This is just a lexical choice and nothing should hang on this.

I borrow this distinction from Shaw (2014).

I borrow this liberal use of “indeterminacy” from Eklund (2008). I’m aware that the alleged indeterminacy of “gavagai” may be quite different from that of “bald”. In choosing “indeterminacy” over “vagueness” my primary aim is to not restrict our attention to soritical vagueness.

The example comes from Dougherty (2013, p. 3).

The example comes from Shafer-Landau (1994).

In the case of garden-variety vagueness, the two competing theories would concern the “cut-off” point. In the case of multidimensionality, the two competing theories would be the two competing rankings of the dimensions of a term that pull in opposite directions.

For the distinction between formal and substantive (or robust or full-blooded) normativity see, e.g., McPherson (2011), Baker (2016) and Woods (2018). Roughly, the idea is this. Morality and grammar are both normative, in a sense: both set standards of correctness and incorrectness. But morality, like epistemology and unlike grammar, etiquette, and legality, is also authoritative. This feature is often captured by saying that substantively normative standards, unlike merely formal ones, are not only “rule-involving”, but also “reason-involving”. To illustrate: it seems conceptually puzzling to say that eating fish is (morally or all-things-considered) wrong, but there is no reason not to do it, or that cancer conspiracy theories are epistemically unjustified, but there is no reason not to believe them. There is nothing equally puzzling about saying that etiquette, the law, or grammar requires Jim to , but Jim has no reason to .

It might be helpful to clarify that in saying that the relevant indeterminacy is “irresolvable” I do not mean to imply that it is something like “immutable”, as if no change in meaning-fixing facts could make the term less indeterminate (by shrinking the borderline area, so to speak). Rather, the claim is that the target indeterminacy is one that, unlike the ordinary one, can’t be safely or innocuously ignored (that is, resolved) on some occasions.

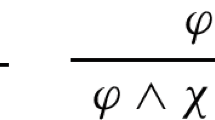

The most popular semantic view on vagueness, supervaluationism (cf. Fine 1975), employs a definition of truth simpliciter (and falsity simpliciter) in terms of supertruth (superfalsity), i.e. truth/falsity relative to all admissible precisifications. This results in some sentences having truth-value gaps. I will make use of no such post-semantic definition of truth here.

For a nice inquiry into the metasemantics of indeterminacy see Eklund (2001).

For an in-depth investigation and assessment of (some of) these moves, see Rohrs (2016) to which the current presentation is especially indebted.

A relativist semantics for vague sentences is sketched and defended by Kölbel (2010). As the reader shall see later on, though, I depart from Kölbel’s supervaluationist pragmatics for vague assertions. See also Rohrs (2016) who claims that supervaluationists should introduce vague propositions if they want a coherent account of the metalanguage of vague statements.

This is not a standard feature of the of the Stalnaker-Lewis view; I’m adding it to cope with indeterminacy.

This follows Hintikka’s well-known account of belief-ascription in his (1969).

I use “implication” as a neutral term to refer to information that is not asserted/said.

This way of framing the explananda draws from MacFarlane (2014). For reasons of space, I leave out the speech act of rejection (basically, the intrapersonal counterpart of rejection) and its respective norms.

I will mainly focus on morality, but I’m inclined to think that my account can be naturally extended to aesthetics, epistemology, and other reason-involving standards. To my knowledge, the view that moral/normative predicates are irresolvably vague/indeterminate was first floated by Aqvist (1964) in a largely unknown paper titled “Vagueness and Value”. Unfortunately, Aqvist’s view is developed in the context of an old-fashioned theory of vagueness according to which borderline predications are meaningless. More recently, Schiffer (1987) and (2003) has advocated a view in the same ballpark. Schiffer’s view, though, is difficult to assess since it is framed in the context of his psychological (contrast: semantic) characterisation of vagueness/indeterminacy. The idea that normative terms are “maximally vague” has recently been advanced and defended in a more elaborate form by Bedke (2018).

In principle, there are various ways of fine-graining my first gloss of “precisification” in the normative context. For instance, one might think of a precisification as a set of very general propositions that encode a normative view (propositions like that killing is wrong, that harming innocents is wrong, etc.), as a “bridge principle” (a folk theory, if you wish) connecting normative terms to non-normative ones by means of conditionals or biconditionals (e.g. x is wrong iff x is D, where “D” stands for a simple or complex descriptive predicate), as a set of propositions describing an ideal world (propositions like that nobody dies, that no innocent is harmed, etc.) as in Lewis-Kratzer style “ordering semantics” (se Kratzer 1981), or yet as a set of conditional rules (“Do/don’t do X in context C”). While there may be reasons to prefer one/some of these approaches over the others, we don’t need to take a stand on this in the present context.

Alternatively, we could picture the disagreement as being not about what precisification to accept for one and the same concept, but rather as a suggestion to jettison the irresolvably indeterminate concept and adopt a different one, i.e. one more determinate.

See Boghossian (1997) for the distinction between metaphysical and epistemological analyticity.

See Williamson (2007).

Some philosophers, like Balaguer (2011) and Cuneo and Shafer-Landau (2014), disagree. Rather than insisting on the correctness of my (and other people’s) intuitions, I will offer a more accommodating response. The starting datum is that seemingly competent speakers have divergent intuitions on the semantic correctness conditions of “wrong” and other normative terms. A possible approach could be to say that this clash of intuitions should be represented by our theory, for example by saying that our linguistic conventions don’t settle things one way or the other—i.e. it is indeterminate whether eccentric uses are linguistically incoherent or not. Although this would require a weakening of the original claim, it wouldn’t really affect the overall import of the foregoing considerations. Indeed, eccentric claims would still fail to be incoherent simpliciter. For an even more accommodating response, though one that I’m less inclined to concede, see fn. 33.

This is a more liberal version of Foot’s (1978) conceptual constraint, which is restricted to humans.

Trivial Descriptivism is a radical view. Someone attracted to a broadly descriptivist approach could adopt a weaker version of my proposal. Instead of saying that substantively normative uses of “ought”, “wrong”, “good” etc. are irresolvably indeterminate, she could say that they are wildly indeterminate, meaning that they have very few clear cases of application. For instance, she could say that torturing innocents for fun or engaging in the recreational slaughter of a fellow person are clear cases of “being wrong”. And she could explain this either in metaphysical terms, or in conceptual terms—in the latter case, by arguing that some substantive moral propositions are conceptual truths (Cuneo and Shafer-Landau 2014), or that accepting some moral sentences is constitutive of being competent with the relevant moral terms (Balaguer 2011).

See the discussion in Sorensen (1990).

Bedke (2018) makes a similar point in fn. 14.

See Gallie (1956) for this notion. Among the conditions defining the essential contestability of a concept, Gallie listed the presence of an authoritative exemplar. An essentially contested concept, thus, unlike an irresolvably indeterminate one, seems to allow for at least one sufficient condition, viz. a feature F such that if x has that feature F, then the application of the concept is mandatory.

One interesting worry, which I’m only going to flag here, is that once we have listed everything that has to go into the semantic core of a normative term (i.e. scope, acceptance of principles, etc.), the resulting semantics looks much more complex than what could be provided by the irresolvable-indeterminacy model alone. This, I think, is true. But it is not something worrisome as long as we acknowledge two points. The first is that any respectable theory of vagueness needs to postulate more machinery than one might initially think (consider, for instance, so called penumbral connection principles). The second, admittedly more radical, is a new perspective on the analogy between vagueness and normativity which we might draw. We could put it this way: perhaps, it’s not so much that normativity is an extreme/special case of vagueness. It’s the other way around: it is vagueness that is a special case of normativity. Thanks to an anonymous referee for drawing me out on this point. I plan to explore these issues in future work.

Someone might not find attractive an analysis on which ordinary vague disagreements (about, say, tallness, baldness, etc.) are handled by positing sameness of content, thereby keeping the precisification information external to what is believed/asserted. I think this worry relates to the difficulty of making sense of relativistic propositions/contents. In this context, let me just note, though, that supervaluationists tend to elude the problem of what vague sentences express, and (to me at least) it’s not clear whether they really keep the precisification information out of the propositional content. The discussion in Rohrs (2016) is especially helpful.

Externalists, like Brink (1989), have long brought attention to amoralists, immoralists, and other psychologically anomalous subjects that are not motivated to act in accordance with the standards they hold. Finlay (2005) and Woods (2014) offer linguistic evidence that the connection between normative assertions and conative attitudes is, in fact, cancellable.

An anonymous referee makes the interesting observation that this sentence doesn’t sound that strange, especially if one replaces the final bit with “even though he’s not actually gay”. To the extent I share this intuition, I think this is due to the nuances of some pejoratives’ meaning. I’m confident that intuitions about the second example in the text are more uniform.

This way of setting things up was inspired by a reading of Bedke (2012b), who identifies the possibility of “reverse open questions” or “ought-is gaps” as the hallmark of thin normativity.

Cf. also Schroeder (2015).

Motivational internalism is, roughly, the view that is an internal and necessary connection between moral judgment and motivation. Of course, my view does entail some sort of internal and necessary relation between making a more judgment and having some sort of pro/con attitude. What I’ve tried to convey is that this need not force us to consider amoralists and immoralists as linguistically incompetent or some such thing.

Karl Pettersson provided me with an illuminating example. Think of an epidemiological statement like the following: (C) “According to the official Swedish statistics, x was the most common cause of death in Sweden in 2012”. In the official statistics, each death is assigned one out of several thousands of codes from the WHO classification (ICD-10) for its main (“underlying”) cause. If x is the most common cause of death, it has to be so relative to certain list, based on a (perhaps only partial) equivalence relation, which partitions the ICD codes in a certain way. However, there are very many such relations. Even if we place a restriction on “admissible relations”, such that the relations should not be completely arbitrary from a medical standpoint, it is safe to say that there is no x such that x is the most common cause of death relative to all admissible relations (e.g. it will vary depending on whether we base the list on ICD chapters or subchapters, or whether we divide certain chapters, such as the large chapter of circulatory disorders, into subchapters).

This line of thought is defended by Silk (2016, pp. 31–32) against the orthodoxy. Silk convincingly argues, in my view, that all parties to the debate can capture their views in the standard Kratzerian framework where modal verbs are context-sensitive in the sense that the context fixes the type/flavour of the reading.

Bibliography

Aqvist, L. (1964). Vagueness and value. Ratio, 6, 121–127.

Baker, D. C. (2016). The varieties of normativity. In T. McPherson & D. Plunkett (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaethics (pp. 567–581). Routledge: Taylor and Francis.

Balaguer, M. (2011). Bare bones moral realism and the objections from relativism. In S. Hales (Ed.), A companion to relativism (pp. 368–390). New York: Wiley.

Bedke, M. (2012a). Against normative naturalism. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 90, 111–129.

Bedke, M. (2012b). The ought-is gap: Trouble for hybrid semantics. Philosophical Quarterly, 62, 657–670.

Bedke, M. (2018). Non-descriptive relativism: Adding options to the expressivist marketplace. Oxford Studies in Metaethics, 13, (pp. 48–70). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blackburn, S. (1993). Essays in quasi-realism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boghossian, P. (1997). Analyticity. In B. Hale & C. Wright (Eds.), A companion to the philosophy of language (pp. 331–368). Oxford: Blackwell.

Brink, D. O. (1989). Moral realism and the foundations of ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Constantinescu, C. (2013). Moral vagueness: A dilemma for non-naturalism. Oxford Studies in Metaethics, 9, 152–185.

Copp, D. (1995). Morality, normativity, and society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cuneo, T., & Shafer-Landau, R. (2014). The moral fixed points: New directions for moral nonnaturalism. Philosophical Studies, 171, 399–443.

Dougherty, T. (2013). Vague value. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 89, 352–372.

Dowell, J. (2013). Flexible contextualism about deontic modals: A puzzle about information-sensitivity. Inquiry, 56, 149–178.

Dreier, J. (1990). Internalism and speaker relativism. Ethics, 101, 6–26.

Dunaway, B. (2016). Ethical vagueness and practical reasoning. The Philosophical Quarterly, 67, 38–60.

Eklund, M. (2001). Supervaluationism, vagueifiers, and semantic overdetermination. Dialectica, 55, 363–378.

Eklund, M. (2007). Characterizing vagueness. Philosophy Compass, 2, 896–909.

Eklund, M. (2008). Deconstructing ontological vagueness. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 38, 117–140.

Field, H. (1973). Theory change and the indeterminacy of reference. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 462–481.

Fine, K. (1975). Vagueness, truth and logic. Synthese, 30, 265–300.

Finlay, S. (2005). Value and implicature. Philosophers’ Imprint, 5, 1–20.

Finlay, S. (2009). Oughts and ends. Philosophical Studies, 143, 315–340.

Finlay, S. (2014). Confusion of tongues: A theory of normative language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Foot, P. (1978). Virtues and vices and other essays in moral philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gallie, W. B. (1956). Essentially contested concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 56, 167–198.

Gibbard, A. (1990). Wise choices, apt feelings. Cambridge, MA: Oxford University Press.

Gibbard, A. (2003). Thinking how to live. Cambridge, MA: Oxford University Press.

Grice, P. (1989). Studies in the ways of words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hare, R. M. (1952). The language of morals. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Harman, G. (1975). Moral relativism defended. Philosophical Review, 84, 3–22.

Harman, G. (2015). Moral relativism is moral realism. Philosophical Studies, 172, 855–863.

Hintikka, J. (1969). Semantics for propositional attitudes. In J. W. Davis, D. J. Hockney, & W. K. Wilson (Eds.), Philosophical logic (pp. 21–45). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Horgan, T., & Timmons, M. (1991). New wave moral realism meets moral twin earth. Journal of Philosophical Research, 16, 447–465.

Horgan, T., & Timmons, M. (1992a). Troubles for new wave moral semantics: The ‘Open Question Argument’ revived. Philosophical Papers, 21, 153–175.

Horgan, T., & Timmons, M. (1992b). Troubles on moral twin earth: Moral queerness revived. Synthese, 92, 221–260.

Horgan, T., & Timmons, M. (2009). Analytic moral functionalism meets moral twin earth. In I. Ravenscroft (Ed.), Minds, Ethics, and Conditionals: Themes From the Philosophy of Frank Jackson (pp. 221–236). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyde, D. (2008). Vagueness, logic and ontology. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Jackson, F. (1998). From metaphysics to ethics: A defence of conceptual analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kölbel, M. (2001). Two dogmas of Davidsonian semantics. Journal of Philosophy, 98, 613–635.

Kölbel, M. (2004). Faultless disagreement. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 104, 53–73.

Kölbel, M. (2008). Truth in semantics. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 32, 242–257.

Kölbel, M. (2010). Vagueness as semantic. In R. Dietz & S. Moruzzi (Eds.), Cuts and clouds (pp. 304–326). Oxford Scholarship Online.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H. J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts: New approaches in word semantics (pp. 38–74). Berlin: Springer.

Lewis, D. (1969). Convention. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1979). Scorekeeping in a language game. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 8, 339–359.

Lewis, D. (1986). On the plurality of worlds. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Lewis, D. (1993). Many, but almost one. In K. Cambell, J. Bacon, & L. Reinhardt (Eds.), Ontology, causality, and mind: Essays on the philosophy of D. M. Armstrong (pp. 23–38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. (1997). Naming the colours. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 75, 325–342.

MacFarlane, J. (2007). Relativism and disagreement. Philosophical Studies, 132, 17–31.

MacFarlane, J. (2014). Assessment sensitivity: Relative truth and its applications. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2016). Vagueness as indecision. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 90, 255–283.

Marconi, D. (2009). Being and being called: Paradigm case arguments and natural words. Journal of Philosophy, 106, 113–136.

McGee, V., & McLaughlin, B. (1995). Distinctions without a difference. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 33, 203–251.

McPherson, T. (2011). Against quietist normative realism. Philosophical Studies, 154, 223–240.

Phillips, D. (1997). How to be a moral relativist. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 35, 393–417.

Plunkett, D., & Sundell, T. (2013). Disagreement and the semantics of normative and evaluative terms. Philosophers’ Imprint, 13, 1–37.

Quine, W. V. O. (1960). Word and object. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Rayo, A. (2010). A metasemantic account of vagueness. In R. Dietz, & S. Moruzzi (Eds.), Cuts and clouds, pp. 23–45.

Ridge, M. (2014). Impassioned belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rohrs, B. (2016). Supervaluational propositional content. Synthese, 194, 2185–2201.

Sainsbury, M. (1990). Concepts without boundaries. In R. Keefe & P. Smith (Eds.), Vagueness. A reader (pp. 251–264). Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

Schiffer, S. (1987). The remnants of meaning. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Schiffer, S. (2003). The things we mean. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schroeder, M. (2013). Tempered expressivism. Oxford Studies in Metaethics, 8, 283–314.

Schroeder, M. (2015). Expressing our attitudes: Explanation and expression in ethics (Vol. 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shafer-Landau, R. (1994). Ethical disagreement, ethical objectivism, and moral indeterminacy. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 54, 331–344.

Shafer-Landau, R. (1995). Vagueness, borderline cases and moral realism. American Philosophical Quarterly, 32, 83–96.

Shapiro, S. (2006). Vagueness in context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shaw, J. R. (2014). What is a truth-value gap? Linguistics and Philosophy, 37, 503–534.

Sider, T. (2001). Criteria of personal identity and the limits of conceptual analysis. Philosophical Perspectives, 15, 189–209.

Sider, T. (2011). Writing the book of the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Silk, A. (2013). Truth conditions and the meanings of ethical terms. Oxford Studies in Metaethics, 8, 195–222.

Silk, A. (2016). Discourse contextualism. A framework for contextualist semantics and pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sorensen, R. A. (1990). Vagueness implies cognitivism. The American Philosophical Quarterly, 27, 1–14.

Stalnaker, R. (1978). Assertion. Syntax and Semantics (New York Academic Press), 9, 315–332.

Toppinen, T. (2013). Believing in expressivism. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford Studies in Metaethics 8 (pp. 252–282) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, R. (2008). Ontic vagueness and metaphysical indeterminacy. Philosophy Compass, 3, 763–788.

Williamson, T. (1994). Vagueness. London: Routledge.

Williamson, T. (2007). The philosophy of philosophy. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wong, D. (1984). Moral relativity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Woods, J. (2014). Expressivism and Moore’s paradox. Philosophers’ Imprint, 14, 1–12.

Woods, J. (2018). The authority of formality. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaethics (pp. 207–229). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Wright, C. (2001). On being in a quandary. Mind, 110, 45–98.

Wright, C. (2006). Intuitionism, realism, relativism and rhubarb. In P. Greenough & M. Lynch (Eds.), Truth and realism (pp. 77–99). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Yablo, S. (2000) “Red, Bitter, Best” critical notice of F. Jackson, from metaphysics to ethics. In Philosophical books, 41, 13–23.

Acknowledgements

I’m especially grateful to Matt Bedke, Renée Bolinger, Aurélien Darbellay, Matti Eklund, Steve Finlay, Andrea Iacona, Manuel García-Carpintero, Max Kölbel, Diego Marconi, Sebastiano Moruzzi, Luigi Perissinotto, Caleb Perl, Giovanni Merlo, Karl Pettersson, Benjamin Rohrs, Henrik Rydéhn, Jack Woods, Jonathan Wright, and three anonymous referees for their helpful comments and criticism.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pravato, G. Indeterminacy and Normativity. Erkenn 87, 2119–2141 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-020-00293-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-020-00293-6