Abstract

This study participates in the discussion of the ethical culture of organizations by deepening the knowledge and understanding of the meaning of organizational ethical virtues in organizational innovativeness. The aim in this study was to explore how an organization’s ethical culture and, more specifically, organization’s ethical virtues support organizational innovativeness. The ethical culture of an organization is defined as the virtuousness of an organization. Organizational innovativeness is conceptualized as an organization’s behavioral propensity to produce innovative products and services. The empirical data consisted of a total of 39 interviews from specialist organizations. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze the data. The findings indicate that the organizational ethical virtues of feasibility, discussability, supportability, and congruency of management are those that support organizational innovativeness. The findings also show which specific elements of these virtues and related organizational practices are important to innovativeness. In addition, this study showed that the features of organizational innovativeness are not necessarily dichotomous but rather follow the ideas of virtues and are versatile in nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Innovativeness has an important role in organizations, as it has been found to be related to their performance, success, and continuity in the long term (e.g., Anderson et al. 2014; Calantone et al. 2002; Salavou 2004). In the current, quickly changing, business world organizations compete with new ideas that can eventually develop into innovations. The role of organizational culture for innovativeness has been shown to be important in previous studies (e.g., Büschgens et al. 2013; Martins and Terblanche 2003; Mumford 2000; Mumford et al. 2002; Naranjo-Valencia et al. 2011; Sarros et al. 2008). Organizational culture can either hold back or promote a creative atmosphere, providing the positive environment necessary for the invention of new ideas (Hult et al. 2004; Martins and Terblanche 2003). In particular, an extensive list of both antecedents and barriers to innovativeness has been recognized in prior research (cf. Anderson et al. 2014). These studies have mainly only listed a set of organizational features that are of relevance for innovativeness instead of discussing the nature, content, and context of these features (Anderson et al. 2014). It can thus be said that previous studies have often simplified the characteristics of innovativeness by both making a dichotomy between antecedents and barriers and listing factors affecting innovativeness without a deeper explanation and understanding of these factors. Instead of repeating this dichotomous view and only listing the affecting factors, we argue here that the link between organizational culture and innovativeness is more multifaceted. For example, specific features of organizational culture might be both enhancers and hinderers of innovativeness. In this article, we focus on the ethical dimension of organizational culture, and specifically a virtue-ethics framework (Kaptein 2008; Solomon 2004) is used to study the ethical culture of an organization (Kaptein 2008) and its meaning for organizational innovativeness.

The ethical culture of an organization builds on seven Corporate Ethical Virtues, namely clarity, congruency, feasibility, supportability, transparency, discussability, and sanctionability, which stimulate employees to ethical conduct (Kaptein 2008). The applied CEV model (Kaptein 1998, 2008) provides one of the most thoroughly developed set of virtues in an organizational setting (Kaptein 2015), which with its specified virtues has been defined, tested, and applied in prior research (De Bode et al. 2013; Huhtala et al. 2011, 2016; Kangas et al. 2014, 2015; Kaptein 2008, 2011, 2015); some research on its linkages to innovativeness exists (Pučėtaitė et al. 2016; Riivari et al. 2012; Riivari and Lämsä 2014). An ethical culture can foster organizational innovativeness in many ways, such as encouraging the formation of open, fair, and cooperative culture that might lead to increased sharing of ideas, and enhancing employees’ positive self-evaluation and identification with their organization. Riivari et al. (2012) and Riivari and Lämsä (2014) studied the link between ethical organizational culture and organizational innovativeness, and showed that the ethical virtues of congruency of management and supervisors can be particularly important features for the innovativeness of the organization, a result that was recently supported in another cultural context by Pučėtaitė et al. (2016). These preliminary findings on the role of an ethical culture in organizational innovativeness suggest that ethical virtues are meaningful in supporting organizational innovativeness.

However, since research has not yet systematically discussed how employees in organizations perceive the meaning of an organization’s ethical culture and ethical virtues in organizational innovativeness, more knowledge of the topic is needed (cf. Blok and Lemmens 2015). Therefore, this study aims to reply to the following research questions: What is the meaning of “ethical culture” in organizational innovativeness? And more specifically, which organizational ethical virtues support organizational innovativeness? Which elements of these virtues are important for supporting organizational innovativeness? Which organizational practices are essential for the virtues that support organizational innovativeness? This study participates in the discussion of the ethical culture of organizations by deepening the knowledge and understanding of the meaning of organizational ethical virtues in organizational innovativeness. In other words, we discuss how an organization’s ethical culture and specific organizational ethical virtues are meaningful for its innovativeness: What are the crucial elements of the virtues and those organizational practices that support innovativeness.

Adopting virtue-ethics theory (Kaptein 2008; Solomon 2004), this study offers a theoretical viewpoint to examine and increase our understanding of the ethical culture of organizations and organizational ethical virtues that take place in organizational practices. According to Collier (1998, p. 646), organizational culture is the medium by which organizational practices are understood and transferred, and ethicality in the organization can be found in these practices. In general, empirical examinations of virtue ethics in research on business ethics have been relatively limited, even though a gradual increase in interest in the topic has occurred (Ferrero and Sison 2014). In particular, there is an urgent need for a more extensive application of the theory in practical situations (Dawson 2015). From an organizational perspective, organizational ethical virtues are not only listings of characteristics or traits but they are also about constantly practicing, developing, and reformulating organizational ethical character (Chun 2005). This study discusses the practical and developmental nature of ethical culture and organizational ethical virtues.

In this study, the ethical culture of an organization, constituted by organizational ethical virtues, illustrates the ethics of an organization, which guides the ethical behavior of organizational members (Key 1999). In addition, ethical culture refers to an organization’s ability to encourage its members to act ethically and avoid committing unethical acts (Collier 1995, 1998; Kaptein 2008; Treviño 1990). Organizational innovativeness is defined as an organization’s behavioral tendency to produce innovative products and services for its customers (Baregheh et al. 2009; Wang and Ahmed 2004); it refers to an organization’s ability to find and develop new ideas that might develop into innovations (Baregheh et al. 2009; Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Wang and Ahmed 2004), and is, therefore, an outcome of the skills and behavior of organizational members. Consequently, it is assumed here that organizational culture, such as an organization’s ethical culture, has an impact on the attainment of outcomes in an organization, such as organizational innovativeness, which in turn may produce innovations. In general, previous studies point out that the organizational culture affects various outcomes from the performance of organizational members, such as their productivity and quality of work, work satisfaction, and organizational commitment (e.g., Brown 1992; Dobni 2008; Erdogan et al. 2006; Giorgi et al. 2015; Holtbrügge et al. 2015; Lemon and Sahota 2004; Martins and Terblanche 2003; Sarros et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2010).

This study makes the following contributions to research on ethical culture and innovativeness in organizations: First, the study aims to conceptualize the meaning of organizational ethical virtues in supporting organizational innovativeness. More specifically, the interest here is in employees’ perceptions of the organizational ethical virtues that they find meaningful for supporting innovativeness. In particular, it is shown that different virtues can be linked to innovativeness in various ways, some more significantly than others. So, from the viewpoint of the development of an ethical culture, this study makes it possible to understand which virtues are critical in that development. Second, the study examines innovativeness from the virtue-ethics perspective and criticizes the often-simplistic view of the features of innovativeness as enhancers or barriers. We add the virtue-ethics perspective to the discussion of organizational innovativeness, and therefore, provide a more comprehensive view of the topic compared to seeing organizational characteristics as only an enhancing or hindering factors of innovativeness. Finally, as earlier empirical studies examining ethical culture and innovativeness in the organization are still limited, this paper aims to study the topic empirically by adding a qualitative perspective. Even though some empirical, qualitative studies on virtue ethics in organizations do exist (e.g., Dawson 2009, 2015; Manz et al. 2011), very few of them have taken a stance that would shed light on the link between various organizational ethical virtues and innovativeness. One example, which is rather close to this idea, is the study by Manz et al. (2011) which examined the role of shared leadership in promoting the sustainable performance of a virtuous organization. According to their findings, the creative process and valuing every organizational member seem to moderate the relationship between leadership and sustainable performance.

Theoretical Framework

Ethical Culture of an Organization and Organizational Ethical Virtues

The ethical culture of an organization has been defined as an organization’s ability to encourage its members to act ethically and avoid committing unethical acts (Collier 1995; Kaptein 2008). It includes the conditions, traditions, and practices of organizational behavior that either promote an organization’s members’ morally sustainable behavior or hinder it (Kaptein 2008; Treviño and Weaver 2003). Drawing upon virtue-ethics theory, Kaptein (2008) states that the ethical culture of an organization builds on organizational ethical virtues that stimulate employees to ethical conduct. In this present article, the ethical culture of an organization is defined as the virtuousness of an organization (cf. Kaptein 2008). Kaptein’s (2008, 2009, 2010) normative and multidimensional CEV model is used to describe the ethical culture of organizations. This model is based on the virtue theory of business ethics (Solomon 2000, 2004), according to which organizations must have certain features or virtues to be ethical. These ethical virtues provide the framework for ethical behavior in the organization and they can also be developed by organizations, although virtues as elements of organizational culture are not easy to change (Kaptein 2009; Schein 2010).

The seven virtues of the CEV model are clarity, congruency, feasibility, supportability, transparency, discussability, and sanctionability (Kaptein 2008). According to Kaptein (2008, p. 924), the first two virtues “relate to the self-regulating capacity of the organization, the next two virtues to the self-providing capacity of the organization, and the last three virtues to the self-correcting or self-cleansing capacity of the organization.” This relates to the main idea of virtue ethics as being, doing, and becoming: First, virtues enhance an organization’s mechanisms to be ethical; second, they support the understanding of the importance of ethics in the organization; and third, they support developing and maintaining ethical organizational behavior in the future. Therefore, we suggest that Kaptein’s (2008) model of the ethical culture of an organization should also include an element of development and organizational learning since these themes are essential in virtue-ethics theory.

The first of the seven virtues, clarity, is related to official expectations concerning the ethical behavior of employees; these expectations should be clear and legitimate (Kaptein 2008). For example, the organization needs to make a clear distinction between ethical and unethical behavior. If there are no explicit rules concerning ethical conduct in the organization, there is a risk that unethical behavior will increase.

The second virtue refers to the congruency of supervisors and of management. This virtue underlines the importance of the supervisors’ and managers’ conduct in the organization, and the fact that they act as role models of ethical or unethical behavior. Congruency implies that supervisors and managers should ensure that their own behavior is in line with the formal requirements of the organization. At the same time, they show other employees that they too should respect the shared expectations of the organization (Kaptein 2008). Congruency is related to the value of integrity, which has been defined as one of the main virtues of business ethics (Solomon 1992a) and also noted as a precondition for trust development in an organization (Mayer et al. 1995).

Feasibility, the third virtue, includes the resources, such as time, money, supplies, tools, and information, that an organization provides for its employees to make it possible for them to meet the official requirements (Kaptein 2008). For example, a decent amount of money and other material resources has been found to be important for innovativeness (Amabile 1988; Amabile et al. 1996; Caniëls et al. 2014), which demonstrates the idea of modesty in virtue ethics, although this idea has not been emphasized in previous creativity and innovation literature.

Supportability is the fourth virtue. It refers to how the organization helps its employees to carry out normative expectations. It is important for the organization to encourage employees to identify and engage with its official expectations and to behave ethically. In practice, supportability means mutual respect, trust, and shared ambition toward the common good in the organization. For example, it has been noted in the previous literature that organizational support, such as feedback and evaluation, should be emphasized to enhance innovative behavior in the organization (Anderson et al. 2014).

The fifth virtue, transparency, is related to employee awareness of the consequences of everyone’s actions. It helps employees to understand what is expected of them in terms of ethical conduct and to take responsibility for their actions. For example, awareness and openness about the consequences of an employee’s behavior toward colleagues, supervisors, and subordinates are part of the virtue of transparency.

The sixth virtue, discussability, refers to employees’ opportunities to talk about ethical topics in the workplace. In practice, the organization should provide channels (e.g., team meetings, roundtable, and unofficial discussions) by which employees can also openly share their ideas about, and perceptions and experiences of ethically relevant topics. These discussion forums should allow individuals to discuss their moral concerns and consider possible mistakes as openings for learning and for providing constructive criticism and feedback.

Finally, the seventh virtue is sanctionability, which refers to the punishment meted out for unethical conduct and the rewards given for ethical conduct. Kaptein (2008) argues that unethical behavior should not be accepted in any form as it might lead to the further acceptance of such behavior, while ethical behavior should be fostered and rewarded. Defining an ethical organizational culture as the virtuousness of the organization has an explicit ethical element. Different virtues foster the importance of integrity when creating and maintaining an ethical culture in an organization.

When creating and developing an ethical culture in an organization, it should be kept in mind that both ethical structures, such as the characteristics and cultural environment of an organization, and ethical individuals are needed (Whetstone 2005). Seeing the organization as a moral agent assumes the presence of virtues or moral excellence, as well as, conversely, a lack of vice (Kaptein 2015; Whetstone 2005). According to Aristotle (2001), virtues are defined as characteristics that are intermediate between extremes and always belong in the mean. Hence, we propose that a reasonable “just right” level of certain organizational ethical virtues, such as feasibility (sufficient resources), support from colleagues and supervisors, and a good working atmosphere, is needed for a virtuous organization.

Organizational Innovativeness and Ethical Organizational Culture

In the current literature, organizational innovativeness has been defined as an organization’s willingness and ability to adopt and encourage new ideas, practices, and procedures that could develop into innovations (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; see also Wang and Ahmed 2004). Organizational innovativeness describes an organization’s tendency toward innovation (Salavou 2004). In general, innovativeness is a crucial factor in organizations (e.g., Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Salavou 2004; Wang and Ahmed 2004), but it should be noted here that having innovativeness in the organization does not necessarily always lead to new or sustainable innovations. For example, innovativeness does not solely assure new innovations or products (Garcia and Calantone 2002; Subramanian and Nilakanta 1996), and being innovative can require ethically dubious features, such as breaking the rules, creating conflict, and taking bad risks (Baucus et al. 2008).

Organizational innovativeness is closely linked to an organization’s objective of being successful, as ideas are developed into new products, services, or processes (Baregheh et al. 2009). Organizational innovativeness requires people who are able to collaborate, share, and integrate their knowledge and expertise (Belbin 1981; Roberts and Fusfeld 1981; Van de Ven 1986). In the present study, organizational innovativeness is defined as the ability to find and promote new ideas in the whole organization, and the atmosphere and conditions that are there before any actual innovations materialize (Baregheh et al. 2009; Wang and Ahmed 2004).

The word innovation derives from the Latin word novus, or new, and could also be defined as “a new idea, method or device” or “the process of introducing something new” (Gopalakrishnan and Damanpour 1994, p. 95). The first of these definitions views innovation as an outcome (e.g., Damanpour 1991) and the second as a process (Sarros et al. 2008). In this study, we view innovativeness as an outcome of organizational elements (cf. Sarros et al. 2008; Wolfe 1994), namely the ethical culture of an organization. This perspective is also supported by prior research where an organization’s culture has been viewed as an essential determinant of innovation (Ahmed 1998, p. 31; Damanpour 1991; Scott and Bruce 1994) and innovativeness (e.g., Brown 1992; Erdogan et al. 2006; Martins and Terblanche 2003; Schumacher and Wasieleski 2013).

In general, it has been noted in the previous literature that ethical aspects are seldom included in the innovation process (e.g., Blok and Lemmens 2015). However, ethical culture is related to organizational innovativeness in different ways: through socialization (e.g., Chatman and Jehn 1994), values (Tesluk et al. 1997) that guide an organization’s members’ behavior (Dobni 2008), positive emotions (Cameron et al. 2004), and management control (Büschgens et al. 2013). As an organization’s ethical culture is established by organizational ethical virtues, it can be argued that the association between an organization’s ethical culture and innovativeness is defined by the main properties of virtues, by their amplifying and buffering characteristics (Cameron et al. 2004). The amplifying characteristics elevate the possible positive effects of ethical virtues for innovativeness and the buffering characteristics can protect the organization from harmful innovativeness, such as taking too high risks or causing conflict or even damage (Cameron et al. 2004).

The ethical culture of an organization can foster organizational innovativeness by strengthening employee identification with the organization and fostering open communication and cooperative behavior among organizational members. Generally, organizational culture supports individuals in internalizing organizational values by influencing employees through different socialization and control processes (Bandura 1971; Büschgens et al. 2013). An ethical organizational culture fosters organizational members’ perceptions of safety, recognition, and appreciation for their work and their contribution to the organization. This can promote employee creativity, willingness to share information, and the ability to both work with others and on their own (Park 2005) and further lead to competence that enhances organizational innovativeness.

Organizational ethical virtues, which form the basis of ethical culture, have been associated with the formation of an organization’s social capital (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998), which is important for the flow of information and resources in the organization (Cameron et al. 2004). Social capital also improves communication, cooperation, and learning in the organization (Adler and Kwon 2002; Leana and Van Buren 1999; Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). These factors are also important for increasing organizational innovativeness (Anderson et al. 2014; Phelps et al. 2012; Phelps 2010). Anderson et al. (2014) discuss how an organization’s social embeddedness has an essential role in knowledge sharing, knowledge use, and knowledge network building, which are necessary features for innovativeness. Social relationships play an important role in the knowledge creation process, which is connected with innovativeness (Phelps et al. 2012). Therefore, it could be stated that ethical culture might influence innovativeness through a socialization process, providing an open and respectable type of culture that creates good opportunities for sharing ideas and learning, which are crucial for innovativeness.

When an organization sets innovativeness as its objective and aims for it through ethical values that are in line with employees’ own values, the employees relate to the organization with positive moral emotions, such as pride and respect toward the organization and its members (Malti and Latzko 2012). Positive emotions (Cameron et al. 2004; Dutton et al. 2010; Ellemers et al. 2013; Fredrickson 2003) can motivate employees to use their expertise and knowledge to achieve the best results for the organization and, also, to employ practices and processes that support innovativeness. As an ethical culture can enhance positive emotions among employees, it can also promote future virtuous behavior, which for their part can boost positive organizational outcomes (Seligman 2002; Staw et al. 1994) such as innovativeness (Akgün et al. 2007). For example, Cameron et al. (2004) found that virtuous behavior is positively related to organizational innovativeness through positive emotions and feelings so that ethical behavior in the organization maintains and develops positive emotions, which are positively linked with the organization’s ability to innovate.

Finally, control theory (Ouchi 1981) views organizational control as management activity that aims to motivate employees to act according to the organization’s objectives (Büschgens et al. 2013). Previous research has shown that both the formal and symbolic power of management has an essential role in innovation (Hansen 2011). Management can investigate the environment for new ideas and bring them into discussions in the organization. In this way, management is thus able to inspire organizational members to adopt new ideas, which is then followed by innovativeness. Managers can also act as role models and encourage employees to be innovative by their own example. Management can enhance a culture of learning and dialogue by giving feedback and using the experience and professional knowledge of specialists, and therefore, encourage innovativeness. As innovativeness is generally hard to measure and observe, social control is the most efficient way to manage innovative activities in an organization (Büschgens et al. 2013). As discussed above, social processes also have a crucial role in building, maintaining, and developing the organization’s culture and shared values. Thus, an ethical organizational culture can act as a control mechanism and provide specific organizational ethical virtues, namely congruency, that enhance innovativeness. Hence, we propose that congruency of supervisors and management can be perceived as an especially meaningful virtue for supporting organizational innovativeness.

Research Methodology

Research Context and Interviewees

In this study, we chose a qualitative approach to investigate the topic using open-ended, in-depth interviews conducted individually with each interviewee. In these interviews, the participants could share in detail their perceptions, ideas, and experiences concerning organizational innovativeness and various good and bad practices promoting or hindering innovativeness. The empirical material consists of altogether 39 semi-structured interviews from three Finnish specialist organizations. The organizations belong both to the public (Organization A) and the private sector (Organizations B and C). All the organizations operate in Finland, but Organization C’s business area also includes the Nordic countries and Eastern Europe. Organization A is a large public-sector organization, Organization B is a medium-sized private-sector organization, and Organization C is a large private-sector organization. Both Organizations B and C operate in industrial services.

The following criteria were used in the selection of sample organizations: First, they are all specialist organizations in their own field, having highly educated employees with specialized knowledge and expertise. All three organizations emphasize the importance of innovativeness, renewal, and creativity in their objectives and strategies. Their highly educated employees are expected to develop and update themselves. Second, all the organizations share similar values and strategic objectives: Themes like openness, equality, reliability, and fairness are emphasized in each organization. All three organizations declare the importance of fairness in their activities toward employees and other stakeholders. They also emphasize the importance and value of expertise and skilled employees, and they want to provide a motivating working atmosphere and good opportunities for their employees in terms of development and training. Consequently, all organizations shared publicly a common idea that ethical and moral values are essential to their operations. At the time of the research, none of the organizations had any official ethical standards or ethical codes; however, ethics as a theme was formulated as one of the principles in their organizational strategy. All these features presented above are generally viewed as a good starting point for building and maintaining an ethical culture and innovativeness in the organization, which makes these organizations interesting for this study.

The youngest interview participant was 27 years old and the oldest 63. Twenty of the interviewees were men, and 19 were women. Twenty-one of the interviewees were working in supervisory positions, and 18 worked in specialist positions. All interviewees were highly educated, with either a university (34/39) or a vocational (5/39) degree. Purposeful sampling was used as the criteria for selecting these interviewees, as is generally accepted in qualitative research (Eisenhardt 1989; Patton 2002). The main criterion for selection was that the interviewees represent their organizations’ personnel well in terms of gender, position in the organization, and education (cf. Riivari and Lämsä 2014). A contact person in each organization assisted us with the selection of interviewees. Anonymity was guaranteed for the interviewees and respondents are referred to using random numerical codes (1–39).

Interviews and Analysis

The interviews lasted from half an hour to nearly 2 h, amounting to over 43 h of material in total (468 pages of transcribed text). The contact person in each organization, having assisted us with potential interviewee selection, made it possible to visit each organization personally and inform the employees of the study and inquire about the possibility of their participation in the interviews. After these initial briefings, the contacts provided us with information about who had volunteered and how to contact them, and we then contacted the interviewees individually.

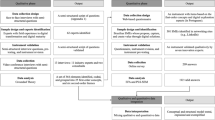

The interviews were carried out face to face, recorded, and later transcribed. The semi-structured interviews consisted of general open-ended questions that were followed by targeted questions about the studied topics to get in-depth and detailed information on interviewees’ perceptions and experiences of the phenomena. The interview was divided into three parts, the first of which consisted of questions about ethical organizational culture, the second of which concerned the interviewees’ ideas about organizational innovativeness, and the third of which consisted of questions related to the relationship between managers and employees. The analysis presented in this article focuses on those sections of the interviews that make reference to organizational innovativeness.

Qualitative content analysis was chosen as a method because it provides a systematic procedure for coding and classifying themes from the text content (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). Content analysis is a classical method of text analysis and is appropriate for categorizing and summarizing material (Krippendorff 2013; Weber 1990). In particular, we chose directed content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon 2005) that could be categorized as a deductive content analysis as it is typically used for retesting or developing existing theory or concepts (Elo and Kyngäs 2008; Marshall and Rossman 1995; Potter and Levine-Donnerstein 1999). We found this approach appropriate as we were interested in the meanings of existing theory, namely the ethical culture of an organization, for organizational innovativeness.

The ATLAS.ti software program was used to support the text analysis. First, we used theory to create analysis categories and chose Kaptein’s (2008) seven organizational ethical virtues as an initial framework to identify the virtues that are meaningful for innovativeness. Second, as our goal was to identify all instances of ethical virtues that make it possible to be innovative in the organization, we carefully read the interview transcripts several times, highlighting quotations (sentences and longer parts of texts) that represented ethical virtues, and next coded the data according to the predetermined categories (Elo and Kyngäs 2008; Hsieh and Shannon 2005). After that, we reviewed how well the quotations fitted to the coding categories and modified the coding if necessary. Simple quantification by counting the frequency of the ethical virtues was also carried out. Our analysis showed that four specific organizational ethical virtues were distinguished as important features for organizational innovativeness.

Findings

In this section, we focus on the four organizational ethical virtues that the interviewees perceived as meaningful for organizational innovativeness. These virtues—(1) feasibility (mentioned 56 times by 23 interviewees), (2) discussability (mentioned 15 times by 12 interviewees), (3) supportability (mentioned 20 times by 12 interviewees), and (4) congruency of supervisors and management (mentioned 26 times by 16 interviewees)—will now be discussed in order to present the findings of the study.

Feasibility

The interviewees indicated that resources for completing their tasks well, especially in their case, time, were essential elements to enhance organizational innovativeness. The interviewees reported that there has to be enough time to complete tasks responsibly and in a way that can be regarded as what was promised. Hurrying and busyness was understood not only as an unethical way of acting but also a barrier to innovative behavior and development of new solutions and working methods that could also refer to process innovativeness. An element that was perceived critical in this sense was that employees have the opportunity and a sense of sufficient time for her/his tasks. The interviewees emphasized that when specialists have a chance to be and feel responsible for their own timetables and schedules, they can find their own best ways to solve problems and find new solutions at work. Even if the work as a specialist usually includes elements like independence and autonomy, it was emphasized that, in particular, when innovativeness is set as an objective of an organization it is extremely significant that enough time to develop new ideas and solutions exists, as the following examples illustrate:

Of course, the tight use of time and other resources eat the innovation out. Even if we could innovate and therefore do things better and quicker and maybe with fewer resources but if we don’t have any chances to innovate, time, we struggle with the issue. Kind of a treadmill. (12)

Well of course, that we have enough time [to innovate]. That we wouldn’t have to choose the most important task, as we typically have to. Then we don’t have the time to be innovative. Or even if you would invent some idea, it would require time to implement that and that we don’t… Exactly that we would have enough time to implement this invention or new idea. (28)

The respondents showed some criticism toward the practices of time management in their organizations. Not all interviewees felt that there is always a chance to take as long as it takes to complete the tasks well and create new ideas, but instead there is a constant rush and a necessity in the organization to do things in a certain way that was not considered as the optimal solution. According to the interviewees, a crucial issue in time management is that continuous updating of new software and technical systems requires a lot of time, and usually that is taken away from other tasks and the development of current work. This was experienced as problematic in relation to the quality of work in general but especially for innovativeness.

A relatively broad job description, which refers to an individual employee’s opportunities to do the work independently, and allows flexibility in time arrangements (e.g., helps to sketch one’s own timetables for solving problems and thinking through new solutions properly as one feels the best), was found to be important in organizational practices to maintain the ethical virtue of feasibility, so that the self-providing capacity of the organization supports behavioral and process innovativeness and is constantly developing. The interviewees also indicated that in addition to having enough time and autonomy for completing the work well, other types of resources such as sufficient tools (e.g., technical systems, software, and programs), supplies, and information were meaningful resources for innovativeness. This is illustrated in the following example:

I think we have enough of all these tools and supplies. I mean all these different kinds of IT tools and programs. And that oneself can have an open mind and is able to think. Instead of being the one who holds things up. (35)

The interviewees reported that the right knowledge and information supports their professional competence (e.g., knowing official rules, instructions, and special characteristics and requirements related to the field), which improves innovative behavior and is a significant basis for professionalism in knowledge-intensive work. It was also noted that from the innovativeness point of view it is not always the best solution to accommodate old knowledge and related routines, but even more important for innovativeness is to be able to find new knowledge and try new working methods. The interviewees emphasized that it is important for employees, both from the innovativeness and value-laden point of view of professionalism, to have chances to develop competences and participate actively in human resource development and other organizational development practices (e.g., professional education) to maintain and expand professional knowledge.

Finally, the interviewees described that in knowledge-intensive organizations, where knowledge creation is crucial for success, professionalism and excellence at work requires from employees that they are ready not only for continuous learning but also open to new social contacts and networking that can act as valuable resources to promote organizational innovativeness. In particular, knowing one’s colleagues and subordinates was mentioned as a vital element in social networking in the organization that can enhance process innovativeness through collective sharing and creating new ideas. From the organization’s point of view, organizing various communication channels and providing forums for social networking and knowledge sharing could enhance innovativeness.

In sum, the findings showed that decent resources, particularly time, autonomy, and professional competence, seem to be meaningful elements of feasibility that support organizational innovativeness, especially process innovativeness related to new working methods and idea creation at work, in the studied specialist organizations. In addition, social networks and particularly opportunities for knowledge sharing between organizational members were perceived as an element that contributes to innovativeness. By “decent” the interviewees meant that there should be enough, not too little or too much, time and autonomy as well as adequate tools and supplies to promote innovativeness. Sufficient resources allow the employees to complete their tasks ethically and well, and furthermore, make it possible to create new ideas, methods and innovate. In professional competence, decency refers to the context and content of the competence, so that deeper knowledge and competences are required in the specialist area of individual employees, while more general knowledge and competence may be sufficient for handling general tasks. This is also in line with the one of the basic ideas of virtue-ethics theory that argues for the importance of the context where the virtues are actualized. Such organizational practices as organizational and human resource development and organizing different forums for knowledge sharing and social networking were found to be essential in supporting organizational innovativeness.

Discussability

The interviewees indicated that opportunities to discuss openly about all kinds of topics, including ethical issues, with colleagues in the organization, and obtain feedback and support from other members of the organization were essential features for innovativeness, especially innovative behavior and processes. The interview participants emphasized that open sharing of thoughts with other organizational members, such as colleagues, in a safe and trusting environment should be possible, so that one can participate in discussions and bring up new ideas in the organization. Even though the ethical virtue of feasibility stresses the role of social contacts and networking as important resources for innovativeness, the respondents put emphasis specifically on the importance of trust in the relationships and networking when the ethical virtue of discussability was discussed. In other words, in addition to various forums and opportunities for social contact and knowledge sharing, it is significant according to the interviewees that the conditions of the social contact and knowledge sharing include the atmosphere of trust, since in such an environment novel ideas can be discussed without fear. These ideas of open discussions and opportunities to share thoughts openly and honestly with other people refer to the organizational ethical virtue of discussability. The following quotes illustrate the role of open discussions in the organization to support information sharing and the freedom to present ideas without fear of being punished, which is perceived important to innovativeness.

These new ideas are accepted and that they are not rejected right away. At least in our team we have a really good team spirit and we can openly discuss if someone has an idea. And develop that idea. You can never know if the idea is good and successful or not, but we don’t have any punishments if the idea fails. If it did not turn into anything special. We have positive attitude at least in our team. (25)

You have to have sensitive antennae with all people. That you discuss with many different individuals, that you don’t get stuck with your own little talking group. And do not barricade yourself into this tower. (31)

I send a message to my people that now we have agreed about this [in the management group]. And many times we discuss these decisions with the teams because one message doesn’t explain everything. So that these decisions would be applied in practice, too. I don’t suddenly remember any case that would have been totally rejected. (24)

The interviewees indicated that discussions that emphasize open-mindedness, interest in new ideas and in developing them, seeking information in novel ways, and constantly improving the way things are done include the requisite elements in an organization to develop organizational innovativeness in a way that was regarded good and appropriate. It was emphasized that it is essential that organizations create conditions, situations, and an open atmosphere so that employees can try new things and share their ideas, as the following quotes illustrate:

Well it is kind of like flexible thinking, that you are ready to greet new ideas and produce them yourself and act in a new way, not rejecting them immediately, a kind of openness. (11)

I had team meetings with these little teams, five or six specialists in one team. I had a list of questions and these discussions were very productive. They gave me something to bring to the management group, such as these objectives and aims. Then we started to ideate that we could arrange this kind of a team-walking day. Since these teams have worked together for a very long time, we could mix up these teams so that they could compare and share their working methods. (29)

The interviewees brought forth that there should be sufficient opportunities to share ideas and discuss different topics. For example, too little openness and knowledge sharing might lead to getting stuck in a rut, and on the other hand, too much discussability might not provide any concrete ideas to address. However, according to the interviewees, not all employees in the organization are anxious to share their good working practices or to change their old habits, which can be seen as a challenge for both ethical behavior and innovativeness in the organization. Further, the respondents mentioned that having an open environment for all kinds of discussions does not self-evidently mean that new ideas, inventions, or processes are developed. It was brought out that in addition to discussing and sharing new ideas, innovativeness also requires open-minded, devoted, and industrious people to develop the ideas further and bring them into practice. The interviewees described that if employees are not open to new ideas, the expectation of creativity and innovativeness should not be too high either. The following quotes represent the challenges of being open to new ideas in the organization:

Of course openness and the flow of information in the whole organization is important. - - I think open discussion and bringing up issues are essential. If we don’t succeed in that then there is no point in expecting anything else. If the first answer is that we have already tried that in the 1960s, forget the whole idea, it doesn’t work. If that is said a few times it is useless to expect anything. (32)

When we discuss these things together, there is somebody that says: “No way are we doing this. We have never done it like this.” But we have quite many people who think that we should change our working methods now, to be different. And that should be the way we could make our impression more tangible. (31)

The above-mentioned elements of discussability, which the interviewees emphasized, refer to the self-correcting capacity of the organization. Therefore, the studied organizations can develop their activities so that innovativeness, specifically innovative behavior, can be possible in the future, when the elements that were experienced as crucial to discussability are included in organizational practices. For example, organizations could provide discussion channels and forums for employees to share their ideas and obtain feedback. In addition, supporting organizational learning both at the level of individual employees and among teams in the organization could promote organizational innovativeness.

In sum, the interviewees emphasized the role of mutual, honest, and reliable discussions, and interest in novel ideas and their continuous development as well as open knowledge sharing in the organization as meaningful elements of the ethical virtue of discussability that enhance innovativeness. From the organization’s point of view it seems to be essential for the ethical virtue of discussability that the organization provides opportunities for its members to share their ideas and develop them together in a safe and open environment where trusting relationships prevail. Organizational practices that were seen to support this virtue are various discussion and feedback forums as opportunities for organizational members to get together to share ideas and obtain feedback from others in the organization. Organizational learning is needed both in and among teams in the organization, and this could be promoted via different types of technical systems and processes in the organization, for example.

Supportability

The interviewees underscored that a good, fair, and encouraging work atmosphere is an essential element of the ethical virtue of supportability in promoting innovative behavior in the organization. The findings show that it is not enough that open discussion and related practices are made possible and used, but it is also important that a positive and honorable atmosphere, albeit with a constructively critical attitude in the workplace and productive cooperation and discussion among the organization members, prevails so that innovativeness can be achieved. The following quotes stress the importance of good and healthy working atmosphere for innovativeness:

I’ve always told to my colleagues that we are going to be here eight hours a day messing with each other. We need to live here in a way that we can be glad when we come to work in the morning, that we don’t feel awkward when we get here. (21)

Many times it feels like those good ideas are just a coincidence. You can’t decide that we use that day for innovating. It doesn’t work like that. It’s a lot about the culture and atmosphere. So that the culture allows that kind of horizontal thinking. (1)

Having congenial people working together was perceived as important so that employees could encourage each other and suggest new solutions and innovative ideas in the organization. For example, on the one hand, having an encouraging atmosphere so that people know that they are doing well and are inspired to try something new was found essential; on the other hand, the atmosphere should also allow missteps or oversights so that employees are not afraid of getting into trouble when creating new ideas. The following quote highlights this notion:

We have people, also very innovative people here, so that there are a lot of new ideas. Of course they also give us encouragement, they make good suggestions. It makes things work, so that people get into things and start developing them. (15)

The interviewees also indicated that it is not always important to be positive toward every new suggestion but rather being constructively positive toward new ideas is more meaningful for innovativeness. Being constructively positive toward new ideas means that the ideas can be both openly discussed and criticized. The interviewees described that an overly positive atmosphere and an “anything goes” attitude might not always be positive for innovativeness as that kind of critique-less atmosphere might not support the best possible ideas and results. On the other hand, the interviewees pointed out that if a good, positive, and open atmosphere is lacking, it might also hinder new ideas because of the general negative attitude that “nothing ever improves or gets better here.” Therefore, supportability and the element of having an open and positive, healthy working atmosphere follow the idea of decency or a golden mean in virtue ethics, as was highlighted by the following interviewee:

Support from colleagues is pretty important, too. Fortunately, we don’t have too much competitive spirit or something like that here. It would be something if your colleague would trip you up when you would be going forward or ideating something new, or that there would be a dispute. We don’t have anything like that. (37)

In addition, as was also highlighted when focusing on the ethical virtue of discussability, the participants indicated that trust among the organization’s members was a meaningful element of supportability that advances innovative behavior. The interviewees described that building trust in the organization takes time and effort. So, a trusting working atmosphere and also the opportunity to be critical were found to be essential in supporting innovativeness so that employees know that nobody will “trip you up or pull the rug from under your feet” (30). Finally, the interviewees described that there should be just the right amount of support, guidance, cooperation, and criticism among organizational members to promote innovativeness, especially innovative behavior and process innovativeness, in the organization. It does not have to be continuous guidance or monitoring but rather providing support when needed. The following quote illustrates the importance of having adequate, not too much or too little, support to be innovative:

The support [from colleagues and supervisors] doesn’t have to be daily or constant guidance but rather giving free rein and trust to do certain things. And when you need, you have the opportunity to ask and get detailed guidance. (13)

In summary, the interviewees underlined the importance of supportability and especially a positive, cooperative, trustful, and constructively critical working atmosphere as significant elements of supportability that promote innovativeness. According to the interviewees, the working atmosphere should be decently supportive, so that just the right amount of support in the organization exists. This will enhance innovativeness. In addition, the interviewees described that if people are not willing to try new things or leave existing routines, even if appropriate elements of supportability prevail in the organization, innovativeness might not occur. An organization can develop supportability by paying attention to such organizational practices as workplace development and building trust in the organization, which aim to enhance a positive and constructively critical, balanced work community to encourage innovativeness in the organization.

Congruency of Supervisors and Management

With regard to leadership, the interviewees indicated that support from the leader was a valuable element of the ethical virtue of congruency for organizational innovativeness. For example, if a specialist had a more challenging job that required more time than usual, it was found indispensable that the supervisor provided support, but also real factual help for completing the challenging task well and successfully. In addition, the interviewees indicated that such features as encouragement and trust from the leader are essential in innovative behavior, so that giving an employee free rein would provide the opportunity to be creative and do things in one’s own way. Shortly put, in general good leadership was found to be the “key to everything” (21).

The interviewees emphasized the meaning of a leader’s positive attitude regarding new ideas as a positive element of congruency in promoting organizational innovativeness. Even if the main operations of the organization were controlled by laws, official rules, and guidelines, the interviewees described the leader’s broadmindedness, inspiration, and encouragement of good behavior, development, and trying new things as crucial. Thus, the good example and ethical role modeling of leaders were found essential for innovative behavior. It was seen as a precondition that supervisors in the organization show by their own example how to act ethically, innovatively, and be creative, so that employees “get the impression that I have to do this too” (15).

Valuing support from the leader as an element of the ethical virtue of congruency, which supports innovativeness, might be related to the nature of the professional work they complete in the specialist organizations. The interviewees indicated that there are a lot of tasks that are dependent on individual employees’ way of solving problems and completing tasks, but on the other hand, there is always a supervisor who has the responsibility that the tasks are completed in a certain time frame and according to certain rules. The following comment depicts this well:

One thing is the attitude of my supervisor. How s/he responds to the ideas that I suggest – that the supervisor accepts my ideas. Listens and gives me the chance to act. (33)

In leadership, being honest, fair, encouraging, reliable, and trustworthy was emphasized as necessary elements of the ethical virtue of congruency for supporting innovativeness. The interviewees indicated that the leader should be able to give support, encourage, and treat her/his subordinates equally, but on the other hand, there should not be too much support or encouragement so that employees still feel that they have the autonomy to do their job. Again, this notion follows the idea of decency and virtues as golden means from Aristotelian ethics. The following example illustrates the potential that there might also be challenges related to the relationship between the leader and subordinate when it comes to ethics and innovativeness:

Is it from respect towards the leader, that people do not produce those new ideas or is it out of fear of leader? Or do people think that this is the leader’s job, we should not interfere. (29)

These leadership features mentioned above (e.g., encouragement, equality, fairness, supportiveness, motivating others) are typical characteristics of transformational leadership (e.g., Bass 1991; Bass and Steidlmeier 1999; Bass et al. 2003). Typically, transformational leadership (e.g., Avolio et al. 1999; Bass and Steidlmeier 1999) is characterized by four components: idealized influence (vision, confidence, high standards for emulation), inspirational motivation (providing followers challenges and meanings to engage in shared goals), intellectual stimulation (incorporating an open design and dynamic into processes of situation evaluation, vision formulation, and patterns of implementation), and individualized consideration (treating each follower as an individuals, providing coaching, mentoring, and growth opportunities) (cf. Bass 1985). As presented above, the interviewees perceived these elements of good leadership practices as crucial for supporting organizational innovativeness. Therefore, according to the interviewees, to be able to advance innovativeness, the ethical virtue of congruency of supervisors seems to require leadership behavior that has characteristics from transformational leadership.

The respondents suggested that sometimes a leader could also be a barrier to innovativeness in the organization. It is easy to speak about ethicality and innovativeness and emphasize these topics in speeches and official statements, but it is not an easy task for an individual supervisor to encourage one’s subordinates, who work as professionally very competent specialists in a certain field and specific topic, to be innovative. The interviewees noted that it is not possible to command anyone to be innovative. This notion brings up the challenge or even dilemma in the supervisor’s role in a specialist organization: On the one hand, supervisors are expected to show transformational leadership and behavior, but at the same time it is not self-evident that each supervisor might have all those skills and can use them well and wisely. For example, the interviewees described how the supervisor might have a lot of creative and new ideas for how to develop the organization or employee competences but she/he might lack the ability to instruct and guide others and view the general picture. These features could be developed in the organization through leadership development practices and training targeted specifically at supervisors.

In general, the idea of innovativeness and how it is created, maintained, and developed in the organization was perceived as quite traditional, top-down, in nature. Interviewees described how values, instructions, and feedback mainly come from the top-down in the organization. The following comment stresses this idea:

And one’s own management needs to act as role models. That it goes down from the top, for us to be able to trust. (34)

Trust in the management and their ethicality might support an innovative atmosphere, but on the other hand, the interviewees also described how the conformism and orthodoxy of the top management might sometimes hinder innovativeness in organizations. Or, there might be good and innovative ideas among the top management but applying them into practice and completing new projects might be the actual challenge, as the following comment illustrates:

The manager has had opportunities to be innovative but it feels as though completing the task at hand does not get that much attention. (28)

In addition, the interviewees indicated that well-articulated objectives and precise guidelines in the organization were essential for setting clear aims for the organization and for innovativeness. However, the interviewees indicated that strict rules set by the top management could also be a challenge regarding innovativeness. Clear rules and standards for good conduct help employees act in expected ways, but on the other hand, overly strict rules that bring everything into line may work against this. The following quotes illustrate this challenge:

Well yeah, this is maybe against the innovativeness this kind of, as efficient as possible, integration of processes and procedures. If there is a certain way to act in one unit, so then the same model is tried to adapt in every unit. “Let’s work like that so that we get the same operations model in everyplace”. Then it might kill the innovativeness a bit. (12)

In sum, the interviewees perceived the role of congruency, especially the elements of transformational leadership behavior in the supervisors and support from the top management, as essential in enhancing organizational innovativeness. As the interviewees described, the intensity of the support and encouragement for good behavior from a manager is significant. The ethical virtue of congruency should also be at an appropriate level, so that employees receive a reasonable level of support when they need it to promote their innovative behavior. The results show that completely free reins or overly strict monitoring might hinder innovativeness. Finally, the ethical behavior and role modeling of the management and executive group of the organization were perceived as requisites for developing and creating new ideas and innovativeness in a way that might finally end up as new innovations, work processes, or products, for example. From the congruency point of view, the capacity of managers to maintain and develop this ethical virtue in the organization is achieved through such organizational practices as management and leadership development and education that can raise the ethical awareness of the managers and provide guidelines for their ethical behavior.

Summary of the Results

Although interest in ethical culture and innovativeness has stirred recently, little research has addressed the meaning of the ethical culture of organizations for organizational innovativeness. Table 1 presents a summary of the results according to the research questions.

First, the findings of this study show that the organizational ethical virtues of feasibility, discussability, supportability, and congruency support organizational innovativeness. This is presented in the first column in Table 1. Specifically, these ethical virtues enhanced behavioral and process innovativeness that refer to creation of new ideas, working methods, and procedures. Second, this study examined the elements of these ethical virtues that are important in supporting organizational innovativeness (second column in Table 1). Adequate resources, such as time, autonomy, tools, supplies and information, and sufficient professional competence, were found to be essential elements of the ethical virtue of feasibility, which then enhances innovativeness. In regard to the ethical virtue of discussability, open discussions and sharing ideas among organizational members, and feedback from other organizational members, were found to be those elements that support organizational innovativeness. In regard to supportability, a cooperative, trustful, and constructively critical working atmosphere and trust among organizational members were those elements essential for innovativeness. Finally, transformational leadership behavior and support from the top management were found to be the crucial elements of the congruency of supervisors and management that enhances organizational innovativeness.

Finally, this study examined organizational practices that are essential for the ethical virtues that support organizational innovativeness. As the results in the third column in Table 1 show, time management, human resource development, organizing communication and feedback channels and providing discussion forums, accommodating organizational learning, building trust in the organization, and providing management and leadership development and training are those organizational practices that were found to be crucial for the ethical organizational virtues of feasibility, discussability, supportability, and congruency that support organizational innovativeness.

Discussion

In line with previous research findings (Huhtala et al. 2011, 2015; Huhtala 2013; Kangas et al. 2015; Kaptein 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011; Riivari and Lämsä 2014; Sinclair 1993; Treviño 1990; Treviño et al. 1998), our findings in this study show that the ethical culture of an organization can advance organizational outcomes, such as organizational innovativeness. In particular, the results of this study highlight that specific organizational virtues support organizational innovativeness. In the studied specialist organizations, which stress innovativeness, renewal, and development in their strategies, the ethical virtues of feasibility, discussability, supportability, and congruency of management seem to provide a fruitful environment for innovativeness. We suggest that encouraging and cultivating these ethical virtues and their central elements, as defined in this research, can be essential for advancing innovativeness, particularly innovative behavior and processes in the organization. In general, this result implies that different organizational ethical virtues can be useful to different organizational outcomes.

Solomon (2004) argues in favor of a sense of virtue in organizational ethics, which refers to cooperation, joint effort, and concern for organizational members. Virtues are not separate from their social environment; rather, they are the core elements that bind the members of an organization together into a virtuous community, and also organizations to society (Solomon 1992b). Therefore, organizations should be considered as communities where people, to be able to achieve excellence, work together toward commonly shared goals, such as organizational innovativeness—a significant goal in contemporary working life organizations. The achievement of this goal for its part serves the greater society’s demands and the public good for the renewal and development of society (Solomon 2004). This study lends support to the idea of Aristotelian virtue ethics that it is not possible to define virtues that would be applicable to all situations. Virtues are contextual and determined by specific roles and circumstances, where organizational behavior and practices are actualized (Collier 1998; Solomon 1992a, 1999).

In virtue ethics, the good characteristics of an actor are viewed as the key element of ethical behavior. These characteristics promote good practices and actions, which are defined as the main goal in creating and maintaining the well-being of individuals and the community at large (Dawson 2009). At the organizational level, virtue ethics is interested in an ethical culture, which takes place in organizational practices (e.g., Collier 1998). Further, virtues in the organizational context refer to constantly practicing, developing, and reformulating the organization’s ethical character (Chun 2005). According to Aristotelian ethics, acting well is the right way to strive to flourish (e.g., Collier 1998). In line with the virtue-based approach to business ethics (Solomon 2004), our findings indicate that it is not only important to have certain organizational ethical virtues manifested in organizational culture to promote innovativeness but the cultivation and development of these ethical virtues in the organization is also essential. Therefore, organizations should pay attention to such organizational practices that support the continuous development of ethical virtues, such as organizational learning, knowledge management, providing discussion and feedback forums and cultivating trust among organizational members to enhance innovativeness.

The findings denote that ethical virtues are not simply enhancers of or barriers to innovativeness that have been quite widely stressed in previous literature (cf. Anderson et al. 2014), but they can include both positive and negative aspects. The ideal situation is when the virtues are at an appropriate level according to the idea of a golden mean in virtue ethics (Kaptein 2015). As we have shown, the features of innovativeness seem to be more versatile and complex in nature than previous research has recognized (Anderson et al. 2014). We suggest that instead of being dichotomously good or bad, the features of innovativeness can hold the form and characteristics of virtues. Further, the findings denote that from the adopted virtue-based view (Solomon 2004; Kaptein 2008) the ideal ethical organizational environment for innovativeness would be an organization in which there is just the right amount of critical ethical virtues; the lack or oversupply of virtues (e.g., having too little or too much time, having too many technical systems, or having a colleague or supervisor constantly monitoring your work) may not be ideal as this might hinder innovativeness. This finding is supported by the theoretical analysis of Kaptein (2015), who explored the extremes of ethical organizational virtues and emphasized the nature of ethical organizational virtues as a means between vices (too much or too little).

It has been discussed in earlier studies that adequate resources (e.g., information, knowledge, expertise, money, time, and materials) are essential in providing employees with opportunities to be creative and innovate (e.g., Caniëls et al. 2014; Scott and Bruce 1994). Stemming from these studies, we found that the ethical virtue of feasibility is not critical only for ethical culture but is also meaningful for enhancing innovativeness in the organization. As our findings suggest, having an optimal amount of feasibility, and especially such elements as decent time and sufficient competence to complete current tasks, solve problems, and create new solutions in a good manner, is needed in the organization to enhance innovativeness. The flip side of feasibility is that there might be a lack or oversupply of resources, which is not an ideal situation for providing a nourishing environment for innovativeness.

Previous research has shown that good interpersonal relations between organizational members, the good quality of employee relationships, and trust are essential in supporting organizational innovativeness (Scott and Bruce 1994; Zakaria et al. 2004). In line with these studies, our results illustrate that the ethical organizational virtues of discussability and supportability seem to be relevant in enhancing organizational innovativeness. For example, such elements of supportability as having an open, trusting, and constructively critical work atmosphere benefit organizational innovativeness by providing a communicative and safe environment for employees to be innovative. This finding is supported by previous research that suggests that an organizational culture where employees can participate and take responsibility enhances organizational productivity (Whetstone 2005, p. 367). Our findings add the perspective of virtues to this previous discussion, and we emphasize that the elements of discussability and supportability (i.e., open discussions, feedback, good working atmosphere) maintain an organization’s ethical excellence but also promote organizational innovativeness.

Prior empirical research has proposed that the ethical virtue of congruency of management has a special role in organizational innovativeness (Riivari and Lämsä 2014). Managerial support and ethical behavior has also been noted as an important antecedent of a good working atmosphere, motivation of employees, creativity, and successful performance (Bassett-Jones 2005; Hansen 2011; Hosmer 1994, 1997; Martins and Terblanche 2003; Rose-Anderssen and Allen 2008). Previous research has noted the importance of the ethics of managers and leaders as they provide ethical guidance in the organization and encourage their followers to achieve organizational objectives (e.g., Brown et al. 2005; Ciulla 2004; Kanungo and Mendonca 1996; Mendonca 2001; Yukl 2006). In line with these prior discussions, our findings show that the ethical conduct and leadership of supervisors and top managers play an important part in the promotion of innovativeness in an organization. Further, our findings indicate that the role of supervisors and management as part of an innovative organization includes such elements as inspiring and stimulating employees and are typically viewed as features of transformational leadership (e.g., Bass 1991). As the original definition for organizational virtues of congruency of supervisors and management does not cover all these aspects of leadership behavior that our findings denote (cf. Kaptein 2008), we suggest that the definition and content of the virtues of congruency of supervisors and management should be extended to cover the inspirational, motivational, and supportive elements of leadership.

Research Limitations and Further Research

This study has some limitations. First, the interviews were conducted only in Finnish specialist organizations. Therefore, this study emphasizes ethical virtues and organizational innovativeness in this organizational and societal context. Since empirical, specifically qualitative, research about ethics and innovativeness is not so common in current research, even if ethics is often considered to be important for organizations (Collier 1998; Crane and Matten 2007; Huhtala et al. 2011; Kaptein 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011; Paine 1997; Pučėtaitė et al. 2010; Riivari et al. 2012; Sims and Brinkmann 2009; Sinclair 1993; Solomon 2004; Treviño 1990; Treviño et al. 1998), and is therefore relevant to investigate, we suggest that the topic would merit more research in other organizational and societal contexts. Additionally, cross-cultural comparisons would be interesting.

Second, the interviewees described their own experiences, views, and ideas about the meaning of ethical culture in supporting innovativeness in the organization. As both ethical culture and innovativeness are organizational level phenomena and made up of more than just the experiences and perceptions of organizational members, this qualitative interview study could capture only a limited perspective on the topic. Therefore, we suggest that an ethnographic study with various data gathering methods such as fieldwork, documentary data, diaries as well as interviews might be a fruitful alternative to obtain more knowledge and a deeper understanding of the topic. However, this study has answered the calls of previous researchers (Huhtala et al. 2011; Riivari and Lämsä 2014) that more qualitative methods are necessary in studies of ethical organizational culture, since these methods can bring out alternative, more detailed and richer, views on the topic. Finally, this study focused mainly on the positive aspects of ethics and innovativeness; however, the study also showed that there might be contradictory elements related to ethics and innovativeness in the organization. We suggest that it would be worth studying possible contradictions or tensions and even the “dark side” of these phenomena in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our aim in this study was to explore how ethical organizational culture and, more specifically, organizational ethical virtues support organizational innovativeness. This study fosters the idea that organizational innovativeness is promoted by the organization’s ethical virtues of feasibility, discussability, supportability, and congruency, which are characterized by specific elements, which make the virtues perceptible in the organization. Based on the findings and following the idea of a golden mean in virtue ethics (Solomon 1999), we suggest that a decent level of virtue is essential in supporting organizational innovativeness. Further, in line with the ideas of virtue ethics (Solomon 1992a, 2004), supporting and developing ethical virtues in the organization through different organizational practices maintains and enhances both the organization’s ethical excellence and organizational innovativeness. In addition, it was shown that the features of organizational innovativeness are not necessarily dichotomous but, rather, follow the ideas of virtues and are versatile in nature.

Change history

08 February 2019

The article Organizational Ethical Virtues of Innovativeness, written by Elina Riivari and Anna-Maija Lämsä, was originally published electronically on the publisher’s internet portal (currently SpringerLink) on 3 March 2017 without open access. With the author(s)’ decision to opt for Open Choice the copyright of the article changed on 7 February 2019 to © The Author(s) 2019 and the article is forthwith distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (<ExternalRef><RefSource>http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/</RefSource><RefTarget Address="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/" TargetType="URL"/></ExternalRef>), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

References

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40.

Ahmed, P. K. (1998). Culture and climate for innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 1(1), 30–43.

Akgün, A. E., Keskin, H., Byrne, J. C., & Aren, S. (2007). Emotional and learning capability and their impact on product innovativeness and firm performance. Technovation, 27(9), 501–513.

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 123–167.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. The Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154–1184.

Anderson, N., Potocnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. doi:10.1177/0149206314527128.

Aristotle. (2001). Nicomachean ethics (W. D. Ross Trans.). South Bend: Infomotions, Inc.

Avolio, B. J., Bass, B. M., & Jung, D. I. (1999). Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the multifactor leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(4), 441–462.

Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. New York, NY: General Learning Press.

Baregheh, A., Rowley, J., & Sambrook, S. (2009). Towards a multidisciplinary definition of innovation. Management Decision, 47(8), 1323–1339. doi:10.1108/00251740910984578.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.