Abstract

A prominent explanation of the evolution of altruism is ‘indirect reciprocity’ where the tracking of reputations in a population promotes altruistic outcomes. This paper investigates the conditions under which the meaning of reputation-tracking signals can co-evolve with altruistic behaviours. Previous work on this question suggests that such a co-evolution is unlikely. In our model, we introduce a mixture of direct and indirect information: individuals directly observe the actions and signals of others with some probability, rather than individuals always relying only upon information conveyed through signals. In this context, we see the co-evolution of altruism and the kind of ‘moral signals’ required for individuals to track reputation. Our interpretation of this model is that, although individuals can sometimes observe the behaviour of their fellows directly, they cannot always do so, and signals evolve to fill this gap. Although ‘can’ does not imply ‘must’—that our model can produce this co-evolution does not establish that we have found the only possible mechanism—we nonetheless consider this an interesting possibility result worthy of further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note the scare-quotes: this is not properly speaking biological altruism since the behaviour is fitness-enhancing in the long-run, so we see that Trivers dissolves the paradox by changing the domain to which ‘altruism’ refers.

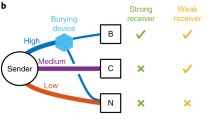

A system of signals where each signal uniquely refers to one and only act as opposed to pooling where a signal does not refer uniquely.

As in Roberts (2015), our main results still obtain even given an initial population of all defectors so this is an admissible simplification.

In order to avoid negative payoffs, each focal individual has their payoff incremented by 1.

We follow Smead in this convention. As Smead notes, this introduces a slight asymmetry into the model. In our case however the large number of interactions within each island in a given generation appears to drown out the effect of this asymmetry.

Smead considers both exogenous and endogenous extensions which attempt to increase the selective pressures toward a signalling system. The exogenous extensions work by increasing the external cost or reward to signalling a certain way. Although such exogenous additions to his basic model do lead to more cooperative populations, as Smead notes, these extensions are less interesting since they seem to push the question back: “[...] where do such exogenous payoffs come from and why should they apply to cases of indirect reciprocity?” (Smead 2010, p. 47).

Note again how our mechanism leverages the idea of direct observation (in this case, of signalling behaviour) and thus depends for its plausibility upon the size of a community. In Smead’s endogenous signal observation model, the idea is that “[...] sending signals in a manner different from others may elicit a form of signal-retaliation and the signaler herself may put her image at stake when making claims about others” (Smead 2010, p. 47). In other words, Smead’s mechanism has an effect on payoffs by potentially altering an individual’s image-score due to an observer disagreeing with how that individual signalled, and that altered image-score may cause the individual to be defected on. In contrast, our mechanism works by allowing discriminators some chance to observe the last signalling behaviour of a potential opponent and then to be ‘choosy’ on this basis. Since both these mechanisms attempt to formalise the idea that “[i]t is possible that signaling a certain way may be something that also elicits future cooperation (or defection)” (ibid., p. 48), they are both endogenous to indirect reciprocity.

These plots, along with all that follow, were generated in Mathematica.

References

Cavalli-Sforza LL, Menozzi P, Piazza P (1996) The history and geography of human genes. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Ghang W, Nowak MA (2015) Indirect reciprocity with optional interactions. J Theor Biol 365:1–11

Leimar O, Hammerstein P (2001) Evolution of cooperation through indirect reciprocity. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B 268:745–753

Nowak MA, Sigmund K (1998) Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature 393:573–577

Nowak MA, Sigmund K (2005) Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature 437:1291–1297

Roberts G (2015) Partner choice drives the evolution of cooperation via indirect reciprocity. PLoS ONE 10(6):1–11

Smead R (2010) Indirect reciprocity and the evolution of “moral signals”. Biol Philos 25(1):33–51

Tanaka H, Ohtsuki H, Ohtsubo Y (2016) The price of being seen to be just: an intention signalling strategy for indirect reciprocity. Proc R Soc Lond B 283:20160694

Trivers RL (1971) The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q Rev Biol 46:35–57

Weibull JW (1995) Evolutionary game theory. MIT Press, Cambridge

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robinson-Arnull, C. Moral talk and indirect reciprocity: direct observation enables the evolution of ‘moral signals’. Biol Philos 33, 42 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-018-9653-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-018-9653-z