Abstract

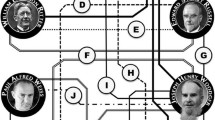

This article is a systematic critical survey of work done in the philosophy of biology within the logical empiricist tradition, beginning in the 1930s and until the end of the 1950s. It challenges a popular view that the logical empiricists either ignored biology altogether or produced analyses of little value. The earliest work on the philosophy of biology within the logical empiricist corpus was that of Philipp Frank, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, and Felix Mainx. Mainx, in particular, provided a detailed analysis of biology in the 1930s and 1940s in his contribution to the logical empiricists’ Encyclopedia of Unified Science. However, the most important contributions to the philosophy of biology were those of Joseph Henry Woodger and Ernest Nagel. Woodger is primarily remembered for deploying the axiomatic method in biology but he also used semiformal methods for the analysis of many biological problems. While Woodger’s axiomatic work was often derided by some later philosophers of biology (e.g., David Hull and Michael Ruse), this article defends both the biological and the philosophical significance of some of that work, for instance, those aspects that led to the recognition of the conceptual complexity of mereology and temporal identity in biological systems. Woodger’s semiformal analyses were even more important, for instance, his explication of the concepts of the Bauplan and of innateness. Nagel’s importance lies in his analyses of reduction and emergence in the context of all empirical sciences and his use of these analyses in a careful exploration of biological problems. While Nagel’s model of reduction was generally rejected by philosophers of science in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly for biological contexts, it has recently been sympathetically reconstructed by many commentators; this article defends its continued relevance for the philosophy of biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hull’s Hull (1974) explicit target was the logical empiricists’ account of reduction but it is clear from the discussions that his skepticism (as noted by Wolters 1999) was not limited to reduction alone. Hull (1973), which is a review of Ruse (1973), explicitly rejects the relevance of all logical empiricist analyses of biology.

In response, Uebel (personal communication, August 4, 2014) has pointed out that when the volume was first being planned around 1998 there was no extant literature documenting attention to biology on the part of the logical empiricists.

Byron (2007) documents the extent of this problem. Note, for instance, Ruse (1973, p. 9): “The author of a book on the philosophy of biology need offer no excuse for the subject he [sic] has chosen, since few areas of philosophy have been so neglected in the past 50 years”; or Hull (1974, p. 6): “The purpose of this book will be to take a closer look at that area of science [biology] which has been passed over in the rapid extrapolation from physics to the social sciences”; or Cohen and Wartofsky (1976, p. v): “The philosophy of biology should move to the center of the philosophy of science—a place it has not been accorded since the time of Mach”; or Rosenberg (1985, p. 13): “In the last few decades, many philosophers have turned their attention to biology to assess the adequacy of a philosophy of science that has been drawn from an almost exclusive examination and reconstruction of physics.” Nicholson and Gawne (2014) go even further by providing numerous self-serving quotations from Hull and, especially, Ruse, spanning decades, all designed to anoint themselves as the founders of the philosophy of biology. Many of these consist of ad hominem attacks on Woodger.

In fact, much of modern molecular biology was created by physicists and chemists with no formal training in biology (Olby 1974; Judson 1979; Sarkar 1989). It would be ironic if the successful practice of biology did not require formal training in biology but the practice of the philosophy of biology does.

This is a quite liberal translation by Woodger but sufficiently faithful to the content of the original not to be corrected here.

Biographical details on Woodger are from Floyd and Harris (1964).

For a critical discussion of this book, as well as Woodger (1929), see Nicholoson and Gawne (2014).

Biographical information on Nagel is from Suppes (1994).

Nagel to Morris, November 16, 1944. Quoted from Reisch (2005, p. 206).

See Hofer (2013) for details.

It is striking that Mainx used “rules” rather than “laws” in future concordance with many post–1970 debates in the philosophy of biology—see, for example, Sarkar (1998).

It is perhaps debatable as to how important it was to evolution. If we take the incorporation of classical genetics (in particular, the work emanating from the Morgan school as well as biochemical genetics) into evolutionary biology as being important, as Haldane (1932) and Wright (1934) clearly did, the issue of reductionism becomes important even in that context. If evolution is taken to be largely comprised of population genetics and systematics (before the molecular turn of the 1960s) the question of reductionism is largely irrelevant. But evolution is not the sole area of biology, and evolutionary biology since the 1950s has also had to engage with the material basis for heredity and diversification.

Thanks are due to Ken Schaffner for drawing my attention to Beckner’s case. There will be no detailed discussion of Beckner’s work because it does not fit well within the logical empiricist canon in spite of Nagel’s involvement.

Sarkar (2015) provides a critical review of this burgeoning literature and a partial defense of Nagel’s model of reduction.

As Nagel (1935, p. 48) observed: “Although chemistry may in some sense be reducible to contemporary physics, it is not the case that it is reducible to the physics of the early nineteenth century.”

On Carnap’s earlier exposition of this model, which is often not recognized (unlike the case of Hempel and Oppenheim), see Sarkar (2013).

The same point was later emphasized by Hempel (1969) within the logical empiricist canon.

Though Schaffner (1967a) is not cited, this point was emphasized by him. Given that Schaffner’s work formed part of a dissertation written under Nagel’s supervision at Columbia University, the former should receive at least some credit for this refinement of Nagel’s analysis.

By “life” Woodger meant “a single organism throughout its whole temporal extent” (1945, p. 96).

The same criticism can also be leveled against Beckner’s (1959) dissertation, written under Nagel’s supervision, which also ignores molecular biology altogether.

Schaffner’s original interest was in reduction in physics. Nagel explicitly required him to include genetics as a case study in his dissertation at Columbia University in the 1960s which was written under Nagel’s supervision (Ken Schaffner, personal communication, 1989).

Ruse (1975) pretends to engage with Woodger’s formal work but does not do so with any subtlety.

References

Abir-Am PG (1987) The biotheoretical gathering, trans-disciplinary authority and the incipient legitimation of molecular biology in the 1930s: new perspective on the historical sociology of science. Hist Sci 25:1–70

Allen GE (1975) Life science in the twentieth century. Wiley, New York

Allen GE (2005) Mechanism, vitalism and organicism in late nineteenth and twentieth-century biology: the importance of historical context. Stud Hist Philos Sci Part C: Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci 36:261–283

Beckner M (1959) The biological way of thought. Columbia University Press, New York

Brigandt I, Love AC (2012) Reductionism in biology. In: Zalta, E. N. Ed. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2012/entries/reduction--biology/

Byron JM (2007) Whence philosophy of biology? Br J Philos Sci 58:409–422

Callebaut W (ed) (1993) Taking the naturalistic turn: or how real philosophy of science is done. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Carnap R (1922) Der Raum. Ein Beitrag zur Wissenschaftslehre.von Reuther und Reichard, Berlin

Carnap R (1923) Über die aufgabe der physik und die anwendung des grundsatzes der einfachstheit. Kant-Studien 28:90–107

Carnap R (1928) Der logische aufbau der welt. Weltkreis-Verlag, Berlin

Carnap R (1934) The unity of science. Kegan Paul, London

Carnap R (1939) Foundations of logic and mathematics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Carnap R (1954) Einführung in die symbolische Logik. Springer, Vienna

Carnap R (1963) Replies and systematic expositions. In: Schilpp PA (ed) The philosophy of Rudolf Carnap. Open Court, La Salle, pp 859–1013

Cohen RS, Wartofsky MW (1976) Preface. In: Grene MG, Mendelsohn E (eds) Topics in the philosophy of biology. Reidel, Dordrecht, pp v–vi

Davidson EH (2010) The regulatory genome: gene regulatory networks in development and evolution. Academic Press, New York

Davidson M (1983) Uncommon sense: the life and thought of Ludwig von Bertalanffy, father of General Systems Theory. J. P, Tarcher, Los Angeles

Delbrück M (1949) A physicist looks at biology. Trans Conn Acad Arts Sci 38:173–190

Driesch H (1914) The history and theory of vitalism. Macmillan, London

Feigl H (1963) Physicalism, unity of science and the foundations of psychology. In: Schilpp PA (ed) The philosophy of Rudolf Carnap. Open Court, La Salle, IL, pp 227–267

Floyd WF, Harris FTC (1964) Joseph Henry Woodger, Curriculum vitae. In: Gregg JR, Harris FTC (eds) Form and strategy in science. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–6

Frank P (1908) Mechanismus oder vitalismus. Versuch einer präzisen Formulierung der Fragestellung. Ann Naturphilos 7:393–409

Frank P (1932) Das Kausalgesetz und seine Grenzen. Springer, Vienna

Gilbert SF, Sarkar S (2000) Embracing complexity: organicism for the 21st century. Dev Dyn 219:1–9

Griesemer JR, Wade MJ (2000) Populational heritability: extending Punnett square concepts to evolution at the metapopulation level. Biol Philos 15:1–17

Griffiths PE (2002) What is innateness? Monist 85:70–85

Haldane JBS (1932) The causes of evolution. Harper and Brothers, London

Haldane JBS (1938a) Biological positivism [review of The Axiomatic Method in Biology by JH Woodger]. Nature 141:265–266

Haldane JBS (1938b) Blood royal: a study of haemophilia in the royal families of Europe. Mod Q 1:129–139

Haldane JBS (1939) The Marxist philosophy and the sciences. Random House, New York

Haldane JBS (1955) A logical basis for genetics? Br J Philos Sci 6:245–248

Haldane JS (1931) The philosophical basis of biology. Hodder and Stoughton, London

Hall BK (1999) Evolutionary developmental biology, 2nd edn. Kluwer, Dordrecht

Hardcastle GL (2007) Logical empiricism and the philosophy of psychology. In: Uebel T, Richardson AW (eds) The Cambridge companion to logical empiricism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 228–249

Hempel CG (1969) Reduction: linguistic and ontological issues. In: Morgenbesser S, Suppes P, White M (eds) Philosophy, science, and method: essays in honor of Ernest Nagel. St. Martin’s Press, New York, pp 179–199

Hempel CG, Oppenheim P (1948) Studies in the logic of explanation. Philos Sci 15:135–175

Henderson LJ (1917) The order of nature: an essay. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Hennig W (1950) Grundzüge einer theorie der phylogenetischen systematik. Deutscher Zentralverlag, Berlin

Hofer V (2002) Philosophy of biology around the Vienna Circle: Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Joseph Henry Woodger and Philipp Frank. In: Heidelberger M, Stadler F (eds) History of philosophy and science. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 325–333

Hofer V (2013) Philosophy of biology in early logical empiricism. Andersen H, Dieks D, Gonzalez WJ, Uebel T, Wheeler, GE Eds New challenges to philosophy of science. Springer, Berlin, pp. 351-363

Hogben L (1930) The nature of living matter. Kegan Paul, Trench, and Trubner, London

Hogben L (1937) Mathematics for the million. Norton, New York

Hull DL (1972) Reduction in genetics-biology or philosophy? Philos Sci 39:491–499

Hull DL (1973) A logical empiricist looks at biology. Br J Philos Sci 28:181–194

Hull DL (1974) Philosophy of biological science. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Hull DL (1994) Ernst Mayr’s influence on the history and philosophy of biology: a personal memoir. Biol Philos 9:375–386

Huxley JS (1942) Evolution: the modern synthesis. Allen and Unwin, London

Judson HF (1979) The eighth day of creation: the makers of the revolution in biology. Simon and Schuster, New York

Kemeny JG, Oppenheim P (1956) On reduction. Philos Stud 7:6–19

Kerr B, Godfrey-Smith P (2002) On Price’s equation and average fitness. Biol Philos 17:551–565

Kitcher P (1984) 1953 and all that. A tale of two sciences. Philos Rev 93:335–373

Kuhn T (1962) The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Loeb J (1912) The mechanistic conception of life: biological essays. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Mainx F (1955) Foundations of biology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Mayr E (1988) Toward a new philosophy of biology: observations of an evolutionist. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Mayr E (2004) The autonomy of biology. Ludus Vital 12:15–27

Morris CW (1938) Foundations of the theory of signs. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Nagel E (1935) The logic of reduction in the sciences. Erkenntnis 5:46–52

Nagel E (1936a) Impressions and appraisals of analytic philosophy in Europe. J Philos 33:5–24

Nagel E (1936b) Impressions and appraisals of analytic philosophy in Europe. J Philos 33:29–53

Nagel E (1939) Principles of the theory of probability. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Nagel E (1949) The meaning of reduction in the natural sciences. In: Stauffe R (ed) Science and civilization. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 99–135

Nagel E (1951) Mechanistic explanation and organismic biology. Philos Phenomenol Res 11:327–338

Nagel E (1952) Wholes, sums, and organic unities. Philos Stud 3:17–32

Nagel E (1961) The structure of science: problems in the logic of scientific explanation. Harcourt, Brace, and World, New York

Nagel E (1970) Issues in the logic of reductive explanation. In: Kiefer HE, Munits MK (eds) Mind, science, and history. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp 117–137

Nagel E (1977) Teleology revisited: functional explanations in biology. J Philos 74:280–301

Nagel E (1977) Teleology revisited: goal-directed processes in biology. J Philos 74:261–279

Needham J (1936) Order and life. Yale University Press, New Haven

Neurath O (ed) (1938) Einheitswissenschaft/Unified science/science unitaire. van Stockun & Zoon, The Hague

Nicholson DJ, Gawne R (2014) Rethinking Woodger’s legacy in the philosophy of biology. J Hist Biol 47:243–292

Nicholson DJ, Gawne R (2015) Neither logical empiricism nor vitalism, but organicism: what the philosophy of biology was. Hist Philos Life Sci 37:345–381

Okasha S (2006) Evolution and the levels of selection. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Okasha S (2008) Fisher’s fundamental theorem of natural selection-a philosophical analysis. Br J Philos Sci 59:319–351

Olby RC (1974) The path to the double helix: the discovery of DNA. University of Washington Press, Seattle

Oppenheim P, Putnam H (1958) The unity of science as a working hypothesis. In: Feigl H, Scriven M, Maxwell G (eds) Concepts, theories, and the mind-body problem. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, pp 3–36

Plutynski A (2006) What was Fisher’s fundamental theorem of natural selection and what was it for? Stud Hist Philos Sci Part C Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci 37:59–82

Raff RA (1996) The shape of life: genes, development, and the evolution of animal form. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Railsback SF, Grimm V (2011) Agent-based and individual-based modeling: a practical introduction. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Reisch GA (2005) How the Cold War transformed philosophy of science. Cambridge University Press, New York

Rieppel, (2003) Semaphoronts, cladograms and the roots of total evidence. Biol J Linnean Soc 80:167–186

Rieppel O (2006) Willi Hennig on transformation series: metaphysics and epistemology. Taxon 55:377–385

Roll-Hansen N (1984) E. S. Russell and J. H. Woodger: the failure of two twentieth-century opponents of mechanistic biology. J Hist Biol 17:399–428

Rosenberg A (1985) The structure of biological science. Cambridge University Press, New York

Ruse M (1973) The philosophy of biology. Hutchinson University Library, London

Ruse M (1975) Woodger on genetics: a critical evaluation. Acta Biotheor 24:1–13

Ruse M (1984) [Review of Aristotle to zoos. Philosophical dictionary of biology by PB Medawar and JS Medawar]. Q Rev Biol 59:453–454

Russell ES (1916) Form and function: a contribution to the history of animal morphology. John Murray, London

Ryckman T (2007) Logical empiricism and the philosophy of physics. In: Uebel T and Richardson AW (eds) The Cambridge companion to logical empiricism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 193–227

Sarkar S (1989) Reductionism and molecular biology: a reappraisal. PhD dissertation. Department of Philosophy, University of Chicago

Sarkar S (1992) Models of reduction and categories of reductionism. Synthese 91:167–194

Sarkar S (1992) Science, philosophy, and politics in the work of J. B. S. Haldane, 1922–1937. Biol Philos 7:385–409

Sarkar S (1996) Lancelot Hogben, 1895–1975. Genetics 142:655–660

Sarkar S (1998) Genetics and reductionism. Cambridge University Press, New York

Sarkar S (2004) Evolutionary theory in the 1920s: the nature of the synthesis. Philos Sci 71:1215–1226

Sarkar S (2005) Biodiversity and environmental philosophy: an introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sarkar S (2008) A note on frequency-dependence and the levels/ units of selection. Biol Philos 23:217–228

Sarkar S (2013) Carnap and the compulsions of interpretation: reining in the liberalization of empiricism. Euro J Philos Sci 3:353–372

Sarkar S (2013) Erwin Schrödinger’s excursus on genetics. In: Harman O, Dietrich M (eds) Outsider scientists: routes to innovation in biology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 93–109

Sarkar S (2014) Does information provide a compelling framework for a theory of natural selection?: grounds for caution. Philos Sci 81:22–30

Sarkar S (2015) Nagel on reduction. Stud Hist Philos Sci Part A 53:43–56

Schaffner KF (1967) Antireductionism and molecular biology. Science 157:644–647

Schaffner KF (1967) Approaches to reduction. Philos Sci 34:137–147

Schaffner KF (1969) The Watson-Crick model and reductionism. Br J Philos Sci 20:325–348

Schaffner KF (2013) Ernest Nagel and reduction. J Philos 109:534–565

Schlick M (1925) Allgemeine Erkenntnislehre. Zweite Auflage, Springer, Berlin

Sober E, Wilson DS (1999) Unto others: the evolution and psychology of unselfish behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Spemann H (1943) Forschung und Leben. J. Engelhorn, Stuttgart

Stadler F (2001) The Vienna Circle: studies in the origin, development, and influence of logical empiricism. Springer, Vienna

Stegmann U (2009) DNA, inference, and information. Br J Philos Sci 60:1–17

Stent GS (1968) That was the molecular biology that was. Science 160:390–395

Suppe F (1974) The search for philosophic understanding of scientific theories. In: Suppe F (ed) The structure of scientific theories. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, pp 1–241

Suppe F (ed) (1974) The structure of scientific theories. University of Illinois Press, Urbana

Suppes P (1994) Ernest Nagel, 1901–1984. Biogr Memoirs Natl Acad Sci (USA) 65:257–272

Timofeeff-Ressovsky NW, Zimmer KG, Delbrück M (1935) Über die Natur der Genmutation und der Genstruktur. Nachrichten der gelehrten Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Mathematischphysikalische Klasse. Neue Folge. Fachgruppe VI 13:190–245

Uebel T (2007) Philosophy of social science in early logical empiricism. In: Uebel T, Richardson AW (eds) The Cambridge companion to logical empiricism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 250–277

Uebel T, Richardson AW (eds) (2007) The Cambridge companion to logical empiricism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

von Bertalanffy L (1928) Kritische theorie der Formbildung. Abhandlungen zur theoretischen Biologie, Gebrüder Borntraeger, Stuttgart

von Bertalanffy L (1930) Tatsachen und Theorien der Formbildung als Weg zum Lebensproblem. Erkenntnis 1:361–407

von Bertalanffy L (1932) Theoretischen biologie. Erster Band: allgemeine theorie, physikochemie, aufbau und entwicklung des organismus. Gebr¨uder Borntraeger, Stuttgart

von Bertalanffy L, Woodger JH (1933) Modern theories of development: an introduction to theoretical biology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Waters CK (1990) Why the anti-reductionist consensus won’t survive: the case of classical Mendelian genetics. In: Fine A, Forbes M, Wessels, L. (eds) PSA 1990: proceedings of the 1990 biennial meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association. Vol. 1. Philosophy of Science Association, East Lansing, pp 125-139

Wilson EB (1923) The physical basis of life. Yale University Press, New Haven

Wimsatt WC (1976) Reductive explanation: a functional account. In: Cohen RS, Hooker CA, Michalos AC (eds) PSA 1974: Proceedings of the 1974 meeting of the philosophy of science association. Reidel, Dordrecht, pp 671-710

Wolters G (1999) Wrongful life: Logico-empiricist philosophy of biology. In: Galavotti MC, Pagnini A (eds) Experience, reality, and scientific explanation. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 187–208

Wolters G (2018) “Wrongful life” reloaded: logical empiricism’s philosophy of biology 1934–1936 (Prague/ Paris/Copenhagen): with historical and political intermezzos. Philos Sci 22:233–255

Woodger JH (1924) Elementary morphology and physiology for medical students: a guide for the first year and a stepping-stone to the second. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Woodger JH (1929) Biological principles: a critical study. Kegan Paul, London

Woodger JH (1937) The axiomatic method in biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Woodger JH (1938) Unity through formalization. Unified Sci 6: 42

Woodger JH (1939) The technique of theory construction. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Woodger JH (1945) On biological transformations. In: Le Gros Clark WE, Medawar P (eds) Essays on growth and form presented to D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 95–120

Woodger JH (1952) Biology and language: an introduction to the methodology of the biological sciences including medicine. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Woodger JH (1953) What do we mean by inborn? Br J Philos Sci 3:319–326

Woodger JH (1956) A reply to Professor Haldane. Br J Philos Sci 7:149–15

Wright S (1934) Physiological and evolutionary theories of dominance. Am Nat 68:24–53

Acknowledgments

The title of this article obviously owes its origin to Stent (1968). This article was written during a summer 2014 visit to the Max-Planck-Insitut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte that was funded by the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD). Thanks are due to the DAAD for support. This article was presented at HOPOS 2014: Tenth International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science Congress in Ghent (Summer 2014) and to the International Philosophy of Biology Circle (Summer 2022); comments by members of both audiences were very helpful and have been incorporated into the text. For discussions and help, thanks are due to Veronika Hofer and Michael Stöltzner; for comments on an earlier draft, thanks are due to Dan Nicholson, Ken Schaffner, and Thomas Uebel.

Funding

There was no external funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interests or competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarkar, S. That was the Philosophy of Biology that was: Mainx, Woodger, Nagel, and Logical Empiricism, 1929–1961. Biol Theory 18, 153–174 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-023-00429-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-023-00429-1