Abstract

In workplace settings, skilled participants cooperate on the basis of shared routines in smooth and often implicit ways. Our study shows how interactional histories provide the basis for routine coordination. We draw on theater rehearsals as a perspicuous setting for tracking interactional histories. In theater rehearsals, the process of building performing routines is in focus. Our study builds on collections of consecutive performances of the same instructional task coming from a corpus of video-recordings of 30 h of theater rehearsals of professional actors in German. Over time, instructions and their implementations are routinely coordinated by virtue of accumulated shared interactional experience: Instructions become shorter, the timing of responses becomes increasingly compacted and long negotiations are reduced to a two-part sequence of instruction and implementation. Overall, a routine of how to perform the scene emerges. Over interactional histories, patterns of projection of next actions emanating from instructions become reliable and can be used by respondents as sources for anticipating and performing relevant next actions. The study contributes to our understanding of how shared knowledge and routines accumulate over shared interactional experiences in publicly performed and reciprocally perceived ways and how this impinges on the efficiency of joint action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Especially in workplace settings, such as theater rehearsals, skilled participants cooperate smoothly (Luff et al., 2000; Mondada, 2014a) on the basis of routines that make their joint work efficient and reliable (Becker, 2005; Feldmann et al., 2016). Well established routines rely on implicit knowledge (Ryle, 1949), they are often discursively not available (Giddens, 1984), and they are embodied (Polanyi, 1966). A prerequisite for routine interaction is the accumulation of shared knowledge over a joint interactional history. One indicator for participants’ reliance on shared knowledge is early responses: a response starts while the sequence-initiating turn is still underway. Early responses rest on anticipations which require shared knowledge about what an ongoing turn is to accomplish and which response is expected (Deppermann et al., 2021). Stable patterns of mutual expectations of action in particular situations constitute routines that enable participants to anticipate next steps and the typical course of the overall activity (Schegloff, 1986).

In this paper, we are interested in how routines emerge. Our question is: How do smooth cooperation and the ability to respond early emerge in social interaction? We focus on a type of knowledge whose emergence can be traced over an interactional history. In contrast to shared cultural knowledge (Clark, 1992, 1996) about interaction types and responses which are likely to be expected to a certain type of first action (as in sales encounters, Mondada & Sorjonen, 2016), knowledge based on shared interactional histories relies on prior joint performances of the same interactional task (Clark & Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986; Deppermann, 2018; Deppermann & Schmidt, 2021b). While the emergence of shared cultural knowledge that covers long periods of time is diffuse, hardly traceable, and extremely dispersed, routines based on shared interactional histories are restricted in terms of relevant situations, time-span of emergence, and social distribution. We trace the emergence of routines by investigating how knowledge is accumulated in consecutive performances of the same instructional task in the context of developing a scene in theater rehearsals.

A methodological prerequisite for tracking longitudinal processes of knowledge accumulation is comparable instances of exchanges by the same participants concerning similar interactional activities and tasks (Pekarek Doehler et al., 2018; Pekarek Doehler & Deppermann, 2021). We draw on theater rehearsals as a “perspicuous setting” (Garfinkel & Wieder, 1992: 184) for tracing (micro-)longitudinal processes of knowledge accumulation in interactional histories (Deppermann & Schmidt, 2021b; Hazel, 2018; Norrthon, 2019). In rehearsals, scenes are repeated multiple times, involving mainly pairs of instructions and instructed actions. Over the rehearsal process, participants, task, and kind of activity remain stable. What has been rehearsed earlier is assumed to be shared knowledge, on which later instructional activities can build. These features of rehearsing create perfect conditions for studying how deployed resources, instructions, and responses to them change over time. Since knowledge-building processes are the declared goal of rehearsals, they are institutions and–methodologically speaking–‘laboratories’ for generating routines.

Our starting point is an episode in which an instructed action is produced ‘early,’ i.e., before the instructed action has reached completion. Chronologically speaking, it is, however, the last episode. We show how the ability to respond ‘early’ rests on shared knowledge which has emerged over an interactional history of the participants. Interactional histories can be tracked over years (Wottoon, 1997) or they can comprise shorter time periods (see Pekarek Doehler et al., 2018; Pekarek Doehler & Deppermann, 2021). In our case, we track only about seven minutes, therefore we speak of ‘micro-histories’. By ‘micro-histories,’ we understand a collection of chronologically ordered instances of executions of the same activity or task by (roughly) the same participants. Our focus is not on the acquisition of individual competence but on the emergence of a coordinative routine and how it affects interactional exchanges. In our case, there are three active participants (one director instructing two actors). The exact number of participants is not crucial; what matters is that a stable group of participants produces shared knowledge together which they can build on in the future as a “community of practice” (Wenger, 2008). We are thus interested in how change happens and what consequences it has.

In the following, we introduce the notion of ‘routines’ (2.1) and its significance for theater rehearsals (2.2). After an overview of the data used and the context of the play (3), we analyze an interactional history of rehearsing a scene based on three consecutive Extracts (4). Finally, we summarize our findings and draw a conclusion (5).

Routines and Varieties of Common Ground

‘Routines’ are considered a key concept in the social sciences because they link structure and action (Pentland & Rueter, 1994: 484). Routines are socially shared (in a community) and, therefore, allow for mutual anticipation of future behavior as well as whole activities in certain situations (Becker, 2005). In socio-phenomenological approaches (Schütz & Luckmann, 1979; Berger & Luckmann, 1969), routines are conceptualized as typified knowledge (e.g., ‘greetings are done with handshakes’) or as habitualized bodily enactments (e.g., the skill of ‘shaking somebody’s hand’). According to this view, routines provide a solution to recurring social problems. Due to their habitualization, routines are seen as ‘cost-saving’ procedures, since less cognitive effort is needed to cope with typical situations. As shared knowledge, they are handed down through generations. In contrast to understanding routines as mechanically followed habits, in the theory of Routine Dynamics within Organizational Studies, they are seen as “situated action” (Suchmann, 1987) that must be continuously and variably adapted in situ to contingencies of the situation (see already Ryle, 1949). Routines always have two aspects: An “ostensive aspect,” which captures the verbal/cognitive representation of a routine, and a “performative aspect,” which refers to the actual and contingent execution of ‘a routine’ in its situational context (Feldman et al., 2016: 506; Lopez-Cotarelo i.pr.). In contrast to Social Phenomenology, EMCA emphasizes that ‘common understanding’ is not a type of knowledge shared between participants but a ‘tacit agreement’ on how things are to be done which can be modified at any time. “The appropriate image of a common understanding is therefore an operation rather than a common intersection of overlapping sets” (Garfinkel, 1967: 30). According to Garfinkel, the routine status of an action is ‘seen but unnoticed’ and makes actions mutually understandable and accountable (Garfinkel, 1967, Heritage, 1984, Yamauchi & Hiramoto, 2016). In this sense, social actions have “routine grounds” (Garfinkel, 1964), and routine is both a condition and an outcome of interaction (Rawls, 2006).

Although routine is a key concept in EMCA (Garfinkel, 1964, 2006), it is rarely defined. The notion of ‘routine’ remains relatively vague, referring to an expectable trajectory of joint activities known (at least in part) by most members of a (usually not further specified) community. Almost all approaches emphasize the tension between stability and flexibility in routines, which makes it difficult to treat different actions as following ‘the same’ routine. Specifically, it remains unclear to what extent routine ways to do things

-

consist of a set of necessary elements (particular embodied actions, turns, TCUs, artifacts etc.);

-

have stable patterns (e.g., sequential structure, ordering of actions etc.);

-

have to be carried out frequently;

-

have to treat the same kind of problems;

-

have to be triggered by the same/similar situations;

-

can be varied without losing the character as ‘the same routine’.

Routines are inextricably linked to progressivity and normativity: They enable expected next actions to be produced without negotiations, delays, repairs, or accounts. Smooth progress without disruptions reflexively indexes that ‘things’ get done in mutual tacit agreement in affiliative ways. According to Schegloff (1986), routines are actively achieved by participants reflexively indicating to each other their choice of a routinized way, thus pre-empting non-routinized variants. Using conversational openings as an example, Schegloff emphasizes: “‘routine’ openings in which ‘nothing happens’ need (..), to be understood as achievements arrived at out of a welter of possibilities for preemptive moves or claims, rather than a mechanical or automatic playings out of pre-scripted routines” (1986: 117). The “impression of routineness” (Schegloff, 1986: 113) created by an “‘uneventful’ joint production” (1986: 148) is based on behavioral features such as latching, terminal overlap, a prosody indexing perfunctoriness (or: superficiality), expectable turn-design and sequence organization that both accomplish and indicate a routine way to conduct exchanges.

One important indicator Schegloff (1986: 114) mentions is “slightly early responses” (latched or overlapping talk). Studies on multimodal interaction have shown that responses to actions are often not only organized sequentially but also partly simultaneously (e.g., Goodwin, 1979; Mondada, 2018a; Stukenbrock, 2018). In particular, bodily conduct can start while an action it responds to is still in the course of its production. Mondada (2014a, 2017, 2018b) has shown that the temporal relationships between instructing first actions and responding bodily second actions can be quite diverse. In contrast to verbal responses, the response can start when the verbal first action is still underway without interruption or overlap. This results in quick and smooth exchanges (Deppermann & Schmidt, 2021a), a strong indicator that participants follow routines.

Projection is a key mechanism for the organization of interaction (Auer, 2005; Streeck, 1995; Streeck & Jordan, 2009; see Deppermann et al., 2021 for an overview). Early responses can build on local projections which emanate from the action they respond to. Projections for next actions before turn-completion can rest on recognition points (Jefferson, 1973; Vatanen, 2018), grammatical formats (Levinson, 2013), gestures and body movement (Deppermann & Schmidt, 2021a; Mondada, 2021) as well as laughter (Jefferson, 1985).

For anticipating next actions, participants also draw on shared knowledge or common ground. Clark (1992, 1996: 92 ff.) defines ‘common ground’ as assumptions about shared knowledge, which participants use to coordinate with each other. Clark (1996) understands routines as part of common ground: “Much of what people take as common ground may be represented in the form of procedures for joint activities. There are the routine actions, such as shaking hands and offering thanks–when, with whom, and how” (1996: 109). Routines can rely on either ‘communal common ground’ or ‘personal common ground’ (Clark, 1992, 1996). The former includes what everybody presumably knows in a certain community, however, with various degrees of certainty and sometime depending on culture, region, class, and age. In EMCA, knowledge of this type can include (1) the overall structural organization of interaction in general or specific activities (Robinson, 2013); (2) interactional (such as Schegloff’s (1986) openings) or occupational standard procedures (Heath et al., 2018; Mondada, 2014a); (3) interaction types and actions which are likely to be expected, like in many institutional interaction settings (Drew & Heritage, 1992).

In addition to local projection and communal common ground, there is a third resource, namely, the common ground which has been accumulated over participants’ shared interactional history.

An adequate understanding of routines that build on shared experience is often only available to members; researchers have to adopt a longitudinal or ethnographic research design to access this group-specific knowledge (Deppermann, 2000, 2013; Deppermann & Schmidt, 2021b). In our study, we focus on a micro-history (see Pekarek Doehler et al., 2018: 16: “micro-genetic”) of rehearsing a scene, in the course of which a routine is developed on how to play the scene. We thus aim to show how the production of early responses and routine cooperation relies on more remote shared experiences in addition to projections provided by the action responded to.

Theater Rehearsals as Institutions of Professional Routine Building

The primary goal of participants in theater rehearsals is to develop a theater production by transforming written texts and abstract aesthetic concepts into an embodied performance. As performances are fluid events (Fischer-Lichte, 2008), acting ensembles aim at developing what we will call ‘performing routines’ enabling them to reproduce a performance in reliable ways. ‘Performing routines’ include agreements on who speaks how and to whom, where people stand, how certain movements are executed, or how transitions between scenes are accomplished (see Norrthon this issue). In contrast to most studies on routine in EMCA (Kelly, 1999), in theater rehearsals, there is no pre-existing routine for how to play the scene which the participants could build on. Instead, the search for a not-yet-existing bodily routine is the focus of the interaction (Lefebvre, 2018). Developing ‘performing routines’ requires the accumulation of new shared knowledge that can be derived neither from community knowledge nor from the script. Their development is guided by professional procedures that ensure the reliable repeatability of routines. The following eight aspects are crucial:

First, routines in (theater) rehearsals are deliberately created by instructing, executing, and discussing the performance (Weeks, 1996, Löfgren & Hofstetter, 2021, Reed & Szczepek Reed, 2014, Schmidt, 2018). Rehearsals are designed to establish “precedents” (Clark, 1996: 81), knowledge of which is presupposed by all participants in the ensemble for the performance.

Second, routines are not already present before the rehearsals in professional theater but are first developed in instructional sequences between directors and actors. In contrast to learning settings, in which students’ implementations are produced and evaluated on the basis of a canonical knowledge (Amerine & Bilmes, 1988, Hsu et al., 2021, Keevallik, 2010, 2015, Szczepek Reed, 2021, Weeks, 1996, Zemel & Koschman, 2014), implementations in creative settings like ours are to be understood as ‘proposals’ (Löfgren & Hofstetter, 2021) that contribute significantly to the development of a (performing) routine that does not yet exist.

Third, performing routines are never just discussed verbally but always exhibited in embodied ways. In contrast to meetings, typically seen as ‘institutions’ to discuss and develop routines explicitly (Feldman et al., 2016: 510; Aroles & McLean, 2016), in theater rehearsals candidates of bodily conduct to become a routine are implemented and tested in situ.

Fourth, developing a routine in theater means that certain courses of action are repeated very often. Training is a resource for practicing and codifying routines (Danner-Schröder & Geiger, 2016). While frequent repetition in learning settings serves to convey existing knowledge (Hsu et al., 2021; Piirainen-Marsh & Alanen, 2012), in our case it is the basis for developing and stabilizing new ideas. Though the script is often a starting point, it falls far short of covering the knowledge that is acquired through repetitive performances.

Fifth, routines in rehearsals are more or less explicitly agreed on.Footnote 1 Usually key features of agreements are written down and made available to all participants.Footnote 2 Rehearsals are designed to minimize the “paradox of mutual knowledge” (Clark, 1992: 14)–people can never know what others know, therefore shared knowledge can only be assumed. This problem is solved by routines since their sharedness is based on joint practice. Because the constitution of routines takes place in the presence of all participants and is considered as agreed upon, the routines created in rehearsals are evident to all and normatively validated.

Sixth, routines are often ‘(pre-)labeled’ (Norrthon, 2021). A key resource for labeling is the script, which provides ways to label a scene. Over the course of rehearsals, (pre-)established labels (the ‘ostensive aspect’), and their implementation (the ‘performative aspect’) are mutually developed.

Seventh, routines are created in theater rehearsals within a comparatively short period of time (usually eight weeks). This allows researchers to record the whole process of the development of the routine, which is impossible for most kinds of routines.

Finally, routines developed in theater rehearsals become visible in particular ways: firstly, through corrective instructions that treat performances as needing improvement on the basis of what was agreed upon previously, and secondly, through their execution in performance, which is the ‘official’ version of a ‘performance routine’.

In contrast to highly formal routines (such as the ‘etcetera-rule,’ ‘let it pass-rule,’ Garfinkel, 1967), which are understood as tacit, universal methods to accomplish interaction, our focus is on normatively obligatory routines that are the focus of a joint professional, task-oriented exchange.

In sum, rehearsals are social encounters designed for building routines. Methodologically, they can be perceived as ‘laboratories’ for an efficient and reliable production of ‘performing routines’.

Data and Methods

Our study draws on longitudinal Conversation Analysis (Pekarek Doehler et al., 2018; Pekarek Doehler & Deppermann, 2021). Theater rehearsals are a ‘perspicuous setting’ (Garfinkel & Wieder, 1992) for investigating change and the accumulation of shared knowledge (Hazel, 2018; Deppermann & Schmidt, 2021b; Norrthon/Schmidt in this issue). In our case the emerging ‘performing routine’ is labeled by phrases that refer to the scene to be performed (‘jumping into his arms’; ‘clinging to his heart’; see Sect. 4). In order to show how a routine emerges, we have analyzed all trial runs of the same scene. The result is a micro-history of the development of a stable ‘performing routine’. In addition, we show how the emerging routine impacts instructional sequences: developing stable ‘performing routines’ allows participants to use shortcuts, and to perform a task faster and without negotiation.

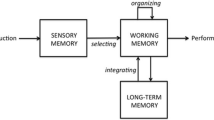

Our study draws on a corpus of 30 h of theater rehearsals of professional actors in German. The data come from a play called Angst.Ich (Fear.I; Fig. 1), which is modeled upon the movie Nosferatu (1922) by the German film director Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. The play tells the classic vampire story in an alienating, postmodern way, reflecting on possible meanings of ‘fear’.

The ensemble includes a director, five actors and two musicians. The play is an independent production of professional theater-makers. In addition to the characters of the Nosferatu film, the main character Hutter, his wife Ellen and the vampire himself, Nosferatu (Duke Orlock), there is a ‘director in the play’ (abbrev. as CoD for co-director in the transcripts), who makes comments and guides the other characters. This creates a meta-level in the play. In addition, Hutter (Ac2) is only allowed to pantomime (i.e., may not speak during the entire performance), while the voice of Nosferatu (Ac1) comes from a tape recorder. Most of the spoken text comes from the subtitles of the 1922 silent movie Nosferatu.

In the scene we focus on, Hutter (H) meets Nosferatu (N) for the first time. For this scene, the script outlines the following directives (see Table 1).

As the second row of the table shows, the choreography gives a rough temporal order of actions to be performed: (1) N addresses H from a distance, (2) N approaches H and jumps into his arms, (3) H holds N in his arms while N is talking, and (4) N climbs back down and moves away from H. In addition, in this scene the tape-recorded voice of N (third row) and the ‘director in the play’ (fourth row) have to produce text lines; some of them serve as cues for the transition between parts of the scene (fifth row). Our analysis concerns the part in which N jumps into H’s arms and H holds N (later labeled by the director as ‘jumping into his arms’). We will refer to this part of the scene as “the heart-figure” (echoing CoD’s nomination at the rehearsal; see Extract 1).

Rehearsing the scene and constructing the heart-figure takes seven minutes, during which it is rehearsed six times (see Table 2).

We selected three extracts, representing four out of the six trial runs:

-

1.

Extract 2 shows how the figure is roughly constructed in two initial trial runs;

-

2.

Extract 3, taken from the middle, shows how the static part of the figure is refined;

-

3.

Extract 1 represents the terminal implementation, in which the figure is built one last time before moving on to the next scene.

Analyses

Terminal Implementation: Building the Figure

We start with the last trial, in which the heart-figure is built by way of an early response. The ‘co-director in play’(CoD; out of frame) instructs two actors on stageFootnote 3; the director (D) does not intervene (Fig. 2).Footnote 4 CoD asks actor 1 (Ac1) to cling to actor 2’s heart (line 02). Actor 1 starts to move towards actor 2 (Ac2) before the instruction is complete.

Extract 1 : you are clinging to his heart (Angst-2b-02:22–02:42) Footnote 5

In line 01, CoD first refers with ‘there’ to the space that the two actors inhabit. By the end of his turn-constructional unit (TCU; Sacks/Schegloff/Jefferson 1974), Ac1 turns his body already towards Ac2 and looks at him (Fig. 3). The declarative reference to the place of both actors by local deictics (‘so you are there’) is enough for Ac1 to expect an instruction concerning his acting with Ac2.

CoD continues his turn in line 02 with ‘and you,' referring to the agent of the instructed action. Ac1 starts to move towards Ac2, who reciprocally turns towards Ac1 and gazes at him (Fig. 4). Although the agent is only referred to pronominally and the type of the instructed action is neither syntactically nor lexically projected yet, Ac1 starts a complying action by approaching his play partner.

Immediately after the verb ‘cling,’ Ac1 starts to lift his arm. In CoD’s turn, the dative object ‘him,' referring to Ac2, follows. Ac2 thus is specified as recipient. He responds with a symmetrical action, lifting his arm as well (Fig. 5). Although the location of where to ‘cling’ to has not been mentioned yet, both actors begin with mutually coordinated movements which–drawing on knowledge accumulated in their interactional history–are recognizable as building ‘the heart-figure’.

After CoD completes his turn by naming the location (‘to his heart’), Ac1 and Ac2 touch each other (Fig. 6) and finally build the figure of ‘Ac1 clinging to Ac2’s heart’ (Fig. 7).

The formulation ‘you are clinging to his heart’ is not a description of how the figure is to be built but a metaphorical label for the accomplished figure. It does not specify who is to perform which action in order to build the figure–CoD’s instruction refers to the figure and not to individual actions.

Both actors cooperate in a straightforward and smooth way. They obviously follow a routine. What is the basis for cooperating this way? Obviously, it is not local projection, salience, or conventional community knowledge that the participants rely on. Rather, they draw on knowledge that has been accumulated over the previous trials. Therefore, we will go back at the participants’ shared interactional history to show how this routine emerged.

Initial Implementation: Constructing the Figure

In Extract 2, the scene containing the ‘heart-figure is rehearsed for the first time. The extract starts with an announcement of the director (D), specifying the next step in the rehearsal as prescribed by the script (‘and now he already jumps into his arms right’):

Extract 2: ‘jumps into his arms’ (Angst-2a-40:45–41:09)

The formulation ‘and now he already jumps into his arms’ (line 12) refers to the scene to be rehearsed next; it builds on shared knowledge of the script. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how the figure is to be physically executed in detail, as no routine can yet be drawn on. It takes 14 s (lines 13 to 26), until the actors produce the first attempt of implementing the figure. In contrast to Extract 1, in which the instruction (‘you are there and you are clinging to his heart,’ lines 01–02) is implemented immediately, the actors’ response in Extract 2 consists of three phases: preparing, negotiating and only bodily (‘technically’) implementing D's instruction. There is obviously no routine yet on how to implement the figure.

First, the actors confirm D’s announcement (lines 14/16). They bodily orient alternately to D and to one another (their play partner), until they establish mutual gaze (Fig. 8).

It follows a verbal negotiation between the two actors about preconditions for building the figure. Ac1’s question ‘will we manage to do that’ (line 20) raises the issue of possible obstacles. Ac2’s response (‘then we just try technically,’ ‘it’s very narrow here,’ lines 25/27) proposes a first try framed as a ‘technical test’ to check the bodily feasibility of the scene, without attending to aesthetic properties. The scene is not yet played in full – among other things, the recorded voice of Ac1 has not yet been played (this only occurs in Extract 3).

Finally, the figure is built by focusing on how the ‘arm-jumping-movement’ can be implemented (Figs. 9, 10: preparations, Fig. 11: completed figure).

While Ac1 and Ac2 hold the figure (Fig. 11), the director proposes an aesthetic improvement (line 29: ‘you can do a bit girlish, David’) beyond the technical realization of the figure. In contrast to the first try, the figure is now built up in two steps, with Ac1 first placing his feet on the seat (Fig. 12) and afterward Ac2 putting his arm under Ac1’s legs (Fig. 14). The resulting modified figure of ‘Ac2 holding Ac1 in his arms’ (Fig. 14) is made salient by Ac1 looking at his stretched and lifted legs to draw Ac2’s attention to them (Fig. 13). Ac1 explicitly proposes this posture as a ‘possibility’ for Ac2 to build the figure (line 39: ‘you just only have to like you can play it like that’). Ac2 complies early by putting his arm through Ac1’s legs and confirms the proposal (line 40). In this way, a possible common solution (a proto-routine) for implementing the figure is developed together. In this second try (lines 31–39), the two actors develop a more complex implementation, which addresses both the technical aspects of building the figure and D’s aesthetic constraint ‘girlish’ (fulfilled by a posture reminiscent of newlyweds; Fig. 14).

Extract 2 exhibits a more complex organization of the instructional activity, including a corrective instruction aiming to improve the performance (lines 13–43). D’s instruction is responded to in several steps, which zoom in on specific aspects (feasibility; spatial conditions, relationship-design (girlish), facial expression). Extract 2 shows how the search for a solution on how to play a scene becomes refined step by step. As Ac2's trouble-implicative question ‘can we do that’ indexes, the way in which the instruction ‘jumping into his arms’ is to be implemented, is not yet fixed and must be developed by trial and error. In this first try, basic behavioral details (“the technical test”) take precedence, while other aspects (such as the spoken lines of CoD or the taped voice of Ac1) are disregarded and come in only incrementally (e.g., the relationship-design of the figure). Yet, technical aspects also feed into the development of aesthetic forms–the ‘girlish’ implementation of the figure leads to an improved solution for how to realize the figure technically. This raises the question of which aspects of the situated implementation are constitutive of the routine to be developed (e.g., the way in which Ac2 holds Ac1’s legs, Fig. 14) vs. which are optional (e.g., Ac2’s strained face, Fig. 14).

In the next three minutes, the figure is refined in several ways (data not shown here):

-

They discuss how the heart-scene should start and end; this involves separating the figure into a dynamic part (how to build it) and a static part (how to hold it); in the transition between building and holding the figure, Ac1 activates his tape voice.

-

The building process of the figure is further refined. Spatial distances between the actors and the keywords that cue building the figure are determined; the way Ac1 approaches Ac2 is rehearsed separately.

Medial Implementation: Refining the Figure

Extract 3 occurs 3 min after Extract 2 (see Table 2). We join the action when the actors have adopted the figure and D produces corrective instructions concerning its shape. Most importantly, the expression ‘heart’ is now introduced.

Extract 3: ‘heart is nice’ (Angst-2b-00:00–01:05)

D’s corrective instruction (line 01: ‘there then more love’) refers to the figure which is enacted. The actors modify their ongoing play accordingly: Ac1 puts his head on Ac2’s chest; Ac2 replies with a disgusted face (line 03; Fig. 15). In contrast to the first instruction in Extract 2, neither preparations nor negotiations precede the implementation in Extract 3. A basic routine for how to build the figure technically has already been established. Moreover, the scene is now performed more completely; the figure is held while the recorded voice of Ac1 (OFF) is played (lines 03, 07, 09). Ac1 waits with his implementation (pause in line 02) until his off-voice has started (line 03: ‘I sleep’). In this way, increasingly more details are incorporated into the routine.

The instruction in line 01 (‘more love’) reinvokes D’s proposal ‘girlish’ from Extract 2. It does not specify a concrete action but refers to an abstract concept, which is to be embodied by the actors. Ac1 (line 03: head on chest) selects one option from a wide range of possibilities of enacting ‘more love’ in this context.

D produces two follow-up instructions: ‘and pull him to you (too)’ (line 06) and ‘not always vex’ (line 11). Both elaborate on category-bound activities (Sacks, 1972) of ‘being in love’. In contrast to D’s prior instruction (‘more love’), she does not just name an abstract concept (‘love’) but specifies how to implement it (e.g., getting closer by touching/pulling on the other’s cloth).

Whereas the positive instruction is immediately implemented by Ac1 grasping und pulling the shirt of Ac2 (line 07; Fig. 16), the negative one (‘not always vexing’) provokes a jocular insertion sequence (lines 12–16). ‘Love’ does not yet seem to be established as a consensual framework for the actors’ relationship; moreover, Ac2’s feelings are only implicitly indexed when D refers to 'playing love' as 'disgusting' (line 40). The routine is still underspecified and negotiable in this respect.

Ac1 then complies with D’s instruction by re-establishing the head-on-shoulder posture (Fig. 17). Ac2 joins in by patting Ac1’s back (line 15). The figure is positively evaluated by D (‘your new flat mate,’ line 17), reinforcing her previous instructions to ‘play love’. She explicitly assesses the performance positively (line 18: ‘this way it’s nice’; line 20: ‘tiloFootnote 6 is good’). D’s instructions, the actors’ implementations and D’s subsequent ratifications represent a typical routine building sequence in rehearsals, in which implementations of instructions are treated as successful and thus as elements of the routine in fieri.

Ac1 and CoD move on to the next scene. After another positive evaluation (line 40: ‘this is also disgusting look how he’), Ac1 introduces a new, uninstructed element by putting his hand on Ac2’s chest (line 40; Fig. 18).

D’s following assessment (line 42: ‘heart is nice davidFootnote 7’) focuses on the new feature and counts as an instruction to retain it in future performances.

At the end of Extract 3 the activity ‘creating the figure’ is replaced by ‘using the figure as a starting point for the next scene’. According to the script, the next scene starts when the ‘director in the play’ (CoD) speaks his lines (line 46: orlock; see Table 2). While in Extract 2, the focus was on establishing the routine, the ‘heart-figure’ now has become a routine and serves to intiate a transition between scenes. However, adopting the figure for moving on to the next scene leads to further ‘depictive proposals’ by the actors (line 40: hand on chest) and evaluations by D (lines 40, 42, 44). Even though the participants are about to move on to the next scene, they are still developing the current scene. Routines in theater are always open to being extended to some degree by new elements. The ‘heart-gesture’ (line 40) emerges when the rehearsal of the figure is actually treated as complete, yet it refines the implementation of the overall aesthetic concept (‘playing love’). In contrast to the basic form of the figure (‘Ac2 holding Ac1 into his arms’), these components are somewhat optional, which becomes clear when these components are sometimes played and sometimes not in later executions. Some of them are instructed, while others are offered without instruction. This gives evidence of the joint creative nature of routine-building in this setting.

The ‘heart figure’ finally is taken as a starting point for the rehearsal of the next scene in Extract 1, which we reproduced here as Extract 4:

Extract 4 : you are clinging to his heart (Angst-2b-02:22–02:42)

In contrast to the previous formulations using verbs of motion (jump, pull, etc.), CoD here uses static verbs (are; cling) that refer to an already established state (‘the heart figure’), whose production is now instructed in one go. Consequently, the figure is not accurately played. At this point, the figure is not rehearsed anymore but taken as given.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have tracked the emergence of a joint bodily routine for performing a scene in a play over a series of trials. The first implementation requires preparations and negotiations and involves a series of instructions, evaluations and corrections. In consecutive trials further specifications, modifications and additions are established. The basic technical infrastructure of the routine is increasingly refined according to aesthetic considerations. During this shared interactional history, the routine emerges and stabilizes. This finally enables the actors to understand what is meant by “clinging to his heart” and to enact the figure early, before the instruction is complete. In our case, the ostensive aspect is modified as well over time. Whereas in the beginning, the description of the script is used (‘jump into his arms’), the final description captures what has been developed together (‘cling to his heart’). This more indexical label indexes a history of a shared routine.

Routine-building in theater rehearsals usually builds on a script. The task in rehearsing a scene is to find a suitable transformation of the text into an embodied play. This transformation is constrained by aesthetic concepts, which may be presupposed or emerge during the rehearsal, such as the concept ‘love’ in our data. Emerging performing-routines are concrete, technical embodiments of both specifications of the script and abstract, aesthetic concepts, without being determined by them. Often, practical implementations and aesthetic concepts are developed by a mutual elaboration, practical implementations being the starting point for conceptual refinements. The concept ‘love’ develops gradually through corrective instructions responding to embodied realizations.

In contrast to other settings (e.g., the routine of ‘hiring a car’), in theater rehearsals the details of the physical execution of the routine are crucial and in focus. They are not important in an instrumental sense, as in cooking lessons (see Mondada, 2014b) or medical training (Zemel & Koschman, 2014, Mondada, 2014a), but in terms of aesthetics. This is because bodily implementations serve to embody visual and auditory aesthetic concepts. They do not serve as means to an end (like a car being hired or a meal being cooked), but the kinesic-visual (or vocal-auditory) routine itself is the goal of rehearsing. Finding and developing an aesthetic solution for how to perform a scene requires establishing a routine for how to play the scene in a repeatable and sustainable way. Repetitions are both a source for creating solutions and for stabilizing a routine in the execution of the solution. By stabilizing routines mainly through embodied repetitions (and not through verbal descriptions), routines are kept flexible, consisting of constitutive core elements (e.g., ‘N. being in H’s arm,’ N. playing ‘love,’ H. being disgusted) and situatively adaptable or optional features (e.g., the degree of H’s strained face, how N. moves in H’s arm).

Routines in theater do not emerge through unsupervised practical experience (as in mundane interaction), nor are they instructed on the basis of prescribed standard procedures (as in school or in formal rituals). Rather, they are creative solutions that are explicitly co-constructed through an interactive process leading to overt agreements. Instructions from directors are often ‘responsive’ (Schmidt & Deppermann, 2020, 2021), as positive instructions confirm and build on actors’ proposals (Löfgren & Hofstetter, 2021), while corrective instructions suppress them (e.g., ‘more love’ vs. ‘not vexing’ in Extract 3). Core elements of the bodily performance may be introduced by actors (e.g., ‘hand to heart’), which can affect the broader aesthetical concept as well (e.g., ‘love’).

Our study shows how routine coordination of actions is an effect of the accumulation of shared knowledge over joint interactional histories. The emergence of behavioral routines and stable mutual expectations lead to shorter instruction sequences. Accounts and negotiations concerning the instruction are means to establish the routine but disappear finally. The timing of responses becomes increasingly compacted: Whereas in initial task performances, delays are usual, in later task performances responses follow more quickly. The history of shared experiences thus is crucial for action-formation and for the temporal organization of sequences (Deppermann, 2018). Over interactional histories, projections of next actions become reliable. This allows participants to anticipate and perform next actions early. In the last instance, the instruction sequence boils down to an adjacency pair of instruction and (early) compliance. The first and the last trial thus differ significantly in terms of progression. Routine is not just a stable behavioral pattern; rather, routine-status is indexed by the design of the actions themselves (e.g., by definite phrases, modal can in early trials but not in later ones).

Data availability

Data are not publicly available.

Notes

German actors call this ‘Verabredungen,’ translatable as ‘agreements’.

In theater, the copy of the script, which includes all cues and notes is known as ‘the book’ or ‘the prompt copy’. It is not to be equated with the routine itself but rather serves as a mnemonic device.

CoD is a ‘co-director in play’. He has an important (speaking) part in this scene, he occasionally also instructs other actors outside his role. If he speaks in role it is italicized in the transcripts.

Both the co-director and the director are also barely visible to the actors on stage, as they stand far away in a dark part of the rehearsal room. Therefore, both actors have to rely on what is conveyed verbally.

Tilo is Ac2.

David is Ac1.

References

Amerine, R., & Bilmes, J. (1988). Following instructions. Human Studies, 11(2), 327–339.

Aroles, J., & McLean, C. (2016). Rethinking stability and change in the study of organizational routines: Difference and repetition in a newspaper-printing factory. Organization. Science., 27(3), 535–550.

Auer, P. (2005). Projection in interaction and projection in grammar. Text, 25(1), 7–36.

Becker, M. C. (2005). Organizational routines: A review of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change, 13(4), 643–677.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1969). Die gesellschaftliche Konstruktion der Wirklichkeit. Eine Theorie der Wissenssoziologie. Frankfurt M Fischer.

Clark, H. H. (1992). Arenas of language use. Univ. of Chicago Press.

Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cabridge Univ. Press.

Clark, H. H., & Wilkes-Gibbs, D. (1986). Referring as a collaborative process. Cognition, 22, 1–39.

Danner-Schröder, A., & Geiger, D. (2016). Unravelling the motor of patterning work: Toward an understanding of the microlevel dynamics of standardization and flexibility. Organization Science, 27(3), 633–658.

Deppermann, A. (2000). Ethnographische Gesprächsanalyse: Zum Nutzen einer Ethnographischen Erweiterung für die Konversationsanalyse. Gesprächsforschung, 1, 96–124.

Deppermann, A. (2013). Analytikerwissen, Teilnehmerwissen und soziale Wirklichkeit in der ethnographischen Gesprächsanalyse. In M. Hartung & A. Deppermann (Eds.), Gesprochenes und Geschriebenes im Wandel der Zeit (pp. 32–59). Verlag für Gesprächsforschung.

Deppermann, A. (2015). Retrospection and understanding in interaction. In A. Deppermann & S. Günthner (Eds.), Temporality in interaction (pp. 57–94). John Benjamins.

Deppermann, A. (2018). Changes in turn-design over interactional histories—The case of instructions in driving school lessons. In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in Embodied Interaction. Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resource (pp. 293–324). John Benjamins.

Deppermann, A., & Gubina, A. (2021). When the body belies the words: Embodied agency With darf/kann ich? (“May/Can I?”) in German. Frontiers in Communication. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.661800

Deppermann, A., & Günthner, S. (2015). Introduction—Temporality in interaction. In A. Deppermann & S. Günthner (Eds.), Temporality in Interaction (pp. 1–23). John Benjamins.

Deppermann, A., Mondada, L., & Pekarek-Doehler, S. (Eds.). (2021). Special issue: Early responses (= Discourse Processes). Taylor & Francis.

Deppermann, A., & Schmidt, A. (2021a). Micro-sequential coordination in early responses. Discourse Processes. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1842630

Deppermann, A., & Schmidt, A. (2021b). How shared meanings and uses emerge over an interactional history: Wabi Sabi in a series of theater rehearsals. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2021.1899714

Drew, P., & Heritage, J. (1992). Analyzing talk at work: an introduction. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at work. Interaction in institutional settings. Cambridge University Press.

Edwards, D. (1997). Discourse and cognition. Sage.

Feldman, M. S., Pentland, B. T., D’Adderio, L., & Lazaric, N. (2016). Beyond routines as things: Introduction to the special issue on routine dynamics. Organization Science, 27(3), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1070

Fetzer, A., & Fischer, K. (2007). Lexical markers of common ground. Elsevier.

Fischer-Lichte, E. (2008). The transformative power of performance: A new aesthetics. Routledge.

Garfinkel, H. (1964). Studies of the routine grounds of everyday activities. Social Problems, 11(3), 225–250.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall.

Garfinkel, H. (2006). Seeing sociologically: The routine grounds of social action. Paradigm Publ.

Garfinkel, H., & Wieder, L. (1992). Two incommensurable, asymmetrically alternate technologies for social analysis. In G. Watson & R. M. Seiler (Eds.), Text in context. Contributions to ethnomethodology (pp. 175–206). SAGE.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press.

Goodwin, C. (1979). The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language (pp. 97–121). Irvington.

Hazel, S. (2018). Discovering interactional authenticity: Tracking theatre practitioners across rehearsals. In S. PekarekDoehler, J. Wagner, & E. González Martínez (Eds.), Longitudinal studies on the organization of social interaction (pp. 255–283). Palgrave, Macmillan.

Heath, C., Luff, P., Sanchez-Svensson, M., & Nicholls, M. (2018). Exchanging implements: The micro-materialities of multidisciplinary work in the operating theatre. Sociology of Health & Illness, 40(2), 297–313.

Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Polity Press.

Hsu, H.-C., Brône, G., & Feyaerts, K. (2021). In other gestures: Multimodal iteration in cello master classes. Linguistics Vanguard. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2020-0086

Jefferson, G. (1973). A case of precision timing in ordinary conversation: Overlapped tag-positioned address terms in closing sequences. Semiotica, 9(1), 47–96.

Jefferson, G. (1985). An exercise in the transcription and analysis of laughter. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 25–34). Academic Press.

Keevallik, L. (2010). Bodily quoting in dance correction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(4), 401–426.

Keevallik, L. (2015). Coordinating the temporalities of talk and dance. In A. Deppermann & S. Günthner (Eds.), Temporality in interaction (pp. 309–366). John Benjamins.

Kelly, R. (1999). Goings on in a CCU: An ethnomethodological account of things that go on in a routine hand-over. Nursing in critical care, 4(2), 85–89.

Lefebvre, A. (2018). Reading and embodying the script during the theatrical rehearsal. Language and Dialogue, 8(2), 261–288.

Levinson, S. C. (2013). Action formation and ascription. In T. Stivers & J. Sidnell (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 103–130). Wiley Blackwell.

Löfgren, A., & Hofstetter, E. (2021). Introversive semiosis in action: Depictions in opera rehearsals. Social Semiotics. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2021.1907180

López-Cotarelo, J., et al. (2021). Ethnomethodology and routine dynamics. In M. S. Feldman (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of routine dynamics. Cambridge Univ Press.

Luff, P., Hindmarsh, J., & Heath, C. (2000). Workplace studies: Recovering work practice and informing system design. Cambridge University Press.

Mondada, L. (2019). Conventions for multimodal transcription. https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription

Mondada, L. (2014a). Instructions in the operating room: How the surgeon directs their assistant’s hands. Discourse Studies, 16(2), 131–161.

Mondada, L. (2014b). Cooking instructions and the shaping of cooking in the kitchen. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, & M. Rauniomaa (Eds.), Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 199–226). John Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2017). Precision timing and timed embeddedness of imperatives in embodied courses of interaction. In M. L. Sorjonen, L. Raevaara, & E. C. Kuhlen (Eds.), Imperative turns at talk (pp. 65–101). John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Mondada, L. (2018a). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction. Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Reseach on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106.

Mondada, L. (2018b). Driving instruction at high speed on a race circuit: Issues in action formation and sequence organization. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 304–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12202

Mondada, L. (2021). How early can embodied responses be? Issues in time and sequentiality. Discourse Processes. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1871561

Mondada, L., & Sorjonen, M. (2016). Making multiple requests in French and Finnish convenience stores. Language in Society, 45, 733–765.

Norrthon, S., & Schmidt, A. (this issue). Knowledge accumulation in theatre rehearsals: The emergence of a gesture as a solution for embodying a certain aesthetic concept.

Norrthon, S. (2019). To stage an overlap-The longitudinal, collaborative and embodied process of staging eight lines in a professional theatre rehearsal process. Journal of Pragmatics, 142, 171–184.

Norrthon, S. (2021). Framing in theater rehearsals: A longitudinal study following one line from page to stage. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, 15(2), 187–214. https://doi.org/10.1558/jalpp.20370

PekarekDoehler, S., & Deppermann, A. (2021). Special Issue: Longitudinal CA: How interactional practices change over time. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(2), 127–240.

PekarekDoehler, S., Wagner, J., & González Martínez, E. (2018). Longitudinal studies on the organization of social interaction. Palgrave Macmillan.

Pentland, B. T., & Rueter, H. H. (1994). Organizational routines as grammars of action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(3), 484–510. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393300

Piirainen-Marsh, A., & Alanen, R. (2012). Repetition and imitation: Opportunities for learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 2825–2828). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_657

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. Doubleday.

Rawls, A. W. (2006). Respecifying the study of social order: Garfinkel’s transition from theoretical conceptualization to practices in details. In H. Garfinkel (Ed.), Seeing sociologically: The routine grounds of social action (pp. 1–97). Paradigm Publ.

Reed, D., & Szczepek Reed, B. (2014). The emergence of learnables in music masterclasses. Social Semiotics, 24(4), 446–467.

Robinson, J. D. (2013). Overall structural organization. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 257–280). Wiley-Blackwell.

Ryle, G. (1949). The concept of mind. Penguin.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735.

Schegloff, E. A. (1986). The routine as achievement. Human Studies, 9, 111–151.

Schmidt, A. (2018). Prefiguring the future: Projections and preparations within theatrical rehearsal. In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 231–260). John Benjamins.

Schmidt, A., & Deppermann, A. (2020). Interaktive emergenz und stabilisierung—Zur Entstehung kollektiver Kreativität in Theaterproben. In J. Reichertz (Ed.), Grenzen der Kommunikation—Kommunikation an den Grenzen (pp. 182–201). Weilerswist.

Schmidt, A., & Deppermann, A. (2021). Instruieren in kreativen Settings—wie Vorgaben der Regie durch Schauspielende ausgestaltet werden. Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift Zur Verbalen Interaktion, 22, 237–271.

Schütz, A., & Luckmann, T. (1979). Strukturen der Lebenswelt (Vol. 1). Suhrkamp.

Selting, M., et al. (2011). A system for transcribing talk-in-interaction: GAT 2. Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift Zur Verbalen Interaktion, 12, 1–51.

Streeck, J. (1995). On projection. In E. N. Goody (Ed.), Social intelligence and interaction: Expressions and implications of the social bias in human intelligence (pp. 87–110). Cambridge Univ. Press.

Streeck, J., & Jordan, S. J. (2009). Projection and anticipation: The forward-looking nature of embodied interaction. Discourse Processes, 46(2–3), 93–102.

Stukenbrock, A. (2018). Forward-looking: where do we go with multimodal projections? In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction. Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 31–68). John Benjamins.

Suchman, L. A. (1987). Plans and situated actions: The problem of human-machine communication. Cambridge Univ. Press.

Szczepek Reed, B. (2021). Singing and the body: Body-focused and concept-focused vocal instruction. Linguistics Vanguard, 7(4), 20200071. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2020-0071

Vatanen, A. (2018). Responding in early overlap: Recognitional onsets in assertion sequences. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(2), 107–126.

Weeks, P. A. D. (1996). A rehearsal of a Beethoven passage. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 29(3), 247–290.

Wenger, E. (2008). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge Univ. Press.

Wootton, A. J. (1997). Interaction and the Development of Mind. Cambridge Univ. Press.

Yamauchi, Y., & Hiramoto, T. (2016). Reflexivity of Routines. Organization Studies, 37(10), 1473–1499.

Zemel, A., & Koschmann, T. (2014). “Put your fingers right in here”: Learnability and instructed experience. Discourse Studies, 16(2), 163–183.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the theatre initiative “sechzig90 Rüsselsheim” and all those involved in the production “Angst.Ich” for their consent to be filmed as well as Farina Stock for the transcriptions.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author 1 has recorded the data, both authors have performed data-analyses and have written the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest..

Consent to participate

Subjects have provided written informed consent to take part in the study.

Consent for publication

Subjects have provided written informed consent for publication of study findings including anonymized data-extracts.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmidt, A., Deppermann, A. On the Emergence of Routines: An Interactional Micro-history of Rehearsing a Scene. Hum Stud 46, 273–302 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-022-09655-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-022-09655-1