Abstract

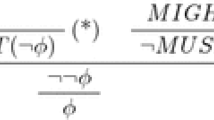

I provide an objection to an argument targeting the claim that epistemic modality concerns what is possible or necessary given what is known. The argument centers around uses of epistemic modals that co-occur with adjuncts of the form ‘according to X’, those in which the content of some reported information is at issue. I argue that such contexts do not license us to reach the sort of conclusion that the argument aims to reach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See section 2 of Faller (2017) for a recent overview of the controversy.

Although I stand by this judgment, see Lassiter (2014) for analogous examples in which the negative judgment is disputed.

This is an oversimplification in several respects. For one thing, we might question whether mere consistency or entailment with a body of knowledge is enough. Perhaps there needs to be some positive evidence, or some non-zero probability, in favor of the prejacent in order for it to count as a possibility. For another, we might question whose knowledge is relevant. Do other conversational participants beside the speaker matter? Does all of the speaker’s knowledge count, or only knowledge that is “shared”? For a recent discussion of the first question, see Hawthorne (2012) and Colgrove and Dougherty (2016). A good deal has been written about the second sort of question, especially in connection with data about disagreement. See Anderson (2014) for a useful overview of this literature.

Kratzer does not formally state an argument in favor of the conclusion that epistemic modals do not have any necessary connection to knowledge. She states the conclusion as though it had been established earlier in the text, but it is not completely obvious which considerations Kratzer has in mind. However, Lisa Matthewson (2015), in presenting the argument that I focus on here, cites “Kratzer (2010),” which is an unpublished manuscript that was eventually revised into “Kratzer (2012).” Matthewson’s presentation of the argument, which I follow below, concerns the data on pages 34–35 of Kratzer (2012), which involves the German reportative sollen and the S

á

á imcets reportative ku7. The data I consider below, which comes from Matthewson (2015), is in English, though this should not matter for the point that I aim to make.

imcets reportative ku7. The data I consider below, which comes from Matthewson (2015), is in English, though this should not matter for the point that I aim to make.Although the focus of this paper is on the Kratzer-Matthewson argument, it is worth noting that the argument’s conclusion—that epistemic modals should not be characterized in terms of knowledge—is shared by semantic theories according to which epistemic modals are interpreted relative to an information state (i.e., a body—any body—of information), such as the theories in Veltman (1996), Yalcin (2007), and Willer (2013).

In the interest of space, I presuppose familiarity with Kratzer’s modal semantic framework. The key aspect of the framework for what follows is that a conversational background is a set of propositions relative to which a given proposition is possible or necessary, where possibility and necessity are treated in terms of consistency with and entailment by the conversational background.

The sentences are used, with different numbers, by Matthewson (2015:156) in presenting the argument. In what follows, I limit the discussion to necessity modals, but the considerations I advance hold mutatis mutandis for modals of any force.

One might object that there is, or may be, a covert epistemic necessity modal operating on the main clause inside the scope of the ‘according to’ phrase in (7). If so, then it might turn out that all uses of ‘according to’ phrases are backgrounding. However, my objection to the Kratzer-Matthewson argument does not depend on whether there are any attributive uses of ‘according to’ phrases.

In the next section, I briefly consider additional data in support of this skepticism.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for pointing out this example and its connection to my arguments in this paper.

The recent popularity of the view, at least among philosophers, originates with its defense in Williamson (2000).

Thanks to Elaine Chun for discussion. I am extremely grateful to five anonymous referees for numerous thoughtful comments that significantly improved this paper.

References

AnderBois, Scott. 2014. On the exceptional status of reportative evidentials. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT), 24, 234–254.

Anderson, Charity. 2014. Fallibilism and the flexibility of epistemic modals. Philosophical Studies 167(3): 597–606.

Colgrove, Nick, and Trent Dougherty. 2016. Hawthorne’s might-y failure: A reply to “Knowledge and epistemic necessity”. Philosophical Studies 173(5): 1165–1177.

Faller, Martina. 2002. Semantics and pragmatics of evidentials in Cuzco Quechua. PhD diss., Stanford University.

Faller, Martina. 2017. Reportative evidentials and modal subordination. Lingua 186–187: 55–67.

von Fintel, Kai, and Anthony Gillies. 2010. Must …stay …strong! Natural Language Semantics 18(4): 351–383.

Hawthorne, John. 2012. Knowledge and epistemic necessity. Philosophical Studies 158(3): 493–501.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2010. Collected papers on modals and conditionals. Published as Kratzer (2012).

Kratzer, Angelika. 2012. Modals and conditionals. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lassiter, Daniel. 2014. The weakness of must: In defense of a Mantra. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT), 24, 597–618.

Matthewson, Lisa. 2015. Evidential restrictions on epistemic modals. In Epistemic indefinites, eds. Luis Alonso-Ovalle and Paula Menéndez-Benito, 141–160. New York: Oxford University Press.

Veltman, Frank. 1996. Defaults in update semantics. Journal of Philosophical Logic 25(3): 221–261.

Willer, Malte. 2013. Dynamics of epistemic modality. Philosophical Review 122(1): 45–92.

Williamson, Timothy. 2000. Knowledge and its limits. New York: Oxford University Press.

Yalcin, Seth. 2007. Epistemic modals. Mind 116(464): 983–1026.

Yalcin, Seth. 2016. Modalities of normality. In Deontic modality, eds. Nate Charlow and Matthew Chrisman, 230–255. New York: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sherman, B. ‘According to’ phrases and epistemic modals. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 36, 627–636 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9376-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9376-x

á

á imcets reportative ku7. The data I consider below, which comes from Matthewson (

imcets reportative ku7. The data I consider below, which comes from Matthewson (