Abstract

Kolodny and MacFarlane have made a pioneering contribution to our understanding of how the interpretation of deontic modals can be sensitive to evidence and information. But integrating the discussion of information-sensitivity into the standard Kratzerian framework for modals suggests ways of capturing the relevant data without treating deontic modals as “informational modals” in their sense. I show that though one such way of capturing the data within the standard semantics fails, an alternative does not. Nevertheless I argue that we have good reasons to adopt an information-sensitive semantics of the general type Kolodny and MacFarlane describe. Contrary to the standard semantics, relative deontic value between possibilities sometimes depends on which possibilities are live. I develop an ordering semantics for deontic modals that captures this point and addresses various complications introduced by integrating the discussion of information-sensitivity into the standard semantic framework. By attending to these complexities, we can also illuminate various roles that information and evidence play in logical arguments, discourse, and deliberation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A simple calculation of expected utility would explain the truth of (2) on its evidence-sensitive reading—using two states (clear, blocked), two acts (stay put, switch routes), and relevant assignments of probabilities to states and utilities to outcomes. However, I remain neutral here on what ultimately makes this normative conclusion correct; consequentialist, deontological, and virtue theories may all ratify it. Also, I bracket just whose evidence is relevant and remain neutral between contextualist and non-contextualist treatments, that is, neutral on whether the relevant evidential state is always supplied from the context or is sometimes supplied from a context of assessment or a parameter of the circumstance of evaluation (see, e.g., Stephenson [84], Yalcin [96], von Fintel and Gillies [23], Dowell [15], Macfarlane [56]; cf . Silk [79]).

Readers who deny that the correct deontic view is such that what we ought to do can be sensitive to features of our limited epistemic position may feel free to embed sentences under, e.g., “Given the truth of X’s beliefs about the correct deontic view.” My distinction between “circumstantial” and “evidence-sensitive” ‘ought’s closely mirrors the common distinction between “objective” and “subjective” senses of ‘ought’. I use ‘circumstantial’ instead of ‘objective’ because such interpretations simply need to be sensitive to certain contextually relevant circumstances; the objective ‘ought’ is a limiting case of this. I avoid calling the evidence-sensitive reading “subjective” for reasons that will become clear below. I use ‘circumstantial’ and ‘evidence-sensitive’ to map onto circumstantial and epistemic modal bases, respectively (see Section 3).

I use the term ‘hypothetical conditional’ in the sense of Iatridou [37].

One might say that we take (7) to be true because we reinterpret it as enthymematic for (8), implicitly assuming that we can learn whether the way is clear (see von Fintel [22]). But I take this suggestion to be something of a non-starter (see Carr [12] for further discussion). First, at least in cases with deontic ‘must’, there seems to be a contrast in acceptability between conditionals with ‘if ψ’ and ‘if we learn that ψ’ as their antecedents:

-

(i)

?If the way is clear, we must switch to the 1.

-

(ii)

If we learn that the way is clear, we must switch to the 1.

Judgments are subtle here. But informal polling suggests that, in the context as described, whereas (i) is dispreferred—we do not have an obligation to switch to the 1 conditional on how the world happens to be—(ii) is true. This suggests that the antecedent in (i) is not reinterpreted as in (ii). It would be odd if the antecedents of deontic ‘ought’ conditionals were reinterpreted in the proposed way but the antecedents of deontic ‘must’ conditionals were not. Second, the reinterpretation move is ad hoc. There is no independent mechanism I know of to motivate why this type of reinterpretation should occur in these examples. In any event, it will be instructive to examine the prospects for developing a semantics that captures how (7) as it stands, is true.

-

(i)

I make the following simplifying assumptions: I treat modal bases as mapping worlds to sets of worlds, rather than to sets of propositions (and use ‘modal base’ to refer sometimes to this function, sometimes to its value given a world of evaluation); I abstract away from details introduced by Kratzer’s ordering source; I make the Limit Assumption ([52, pp. 19–20]) and assume that our selection function is well-defined and non-empty; and I bracket differences in quantificational strength between weak and strong necessity modals. For semantics without the Limit Assumption, see Lewis [52, 54], Kratzer [46, 47], Swanson [88]. On the distinction between weak and strong necessity modals, I prefer the account in Silk [77, 78].

Thanks to Eric Swanson for this way of putting the point.

More formally: Suppose (2) is true in the world of evaluation w, and the way happens to be clear in w. Then \(\forall w' \in D(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w), \lesssim _{w}):\) we stay put in w′. Suppose the world of evaluation w is one such world \(w' \in D(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\); accordingly, we stay put in w. As noted above, \(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w') \subset f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\); and suppose that \(\forall w''' \in f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w): \forall u, v \in f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'''): u \lesssim _{w'''} v \Leftrightarrow v \lesssim _{w'''} u\). (Weaker assumptions would suffice for our purposes, but these make the problem more transparent.) Then \(w \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'), \lesssim _{w'})\). So, since the way is clear in w, \(\exists w' \in f^{+}_{\mathrm {epist}}(w): \exists w'' \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'), \lesssim _{w'}):\) we stay put (and thus don’t switch to the 1) in w″—namely, where w = w′ = w″. But (7) says that \(\forall w' \in f^{+}_{\mathrm {epist}}(w): \forall w'' \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'), \lesssim _{w'}):\) we switch to the 1 in w″. Contradiction.

This amounts to a denial of the assumption articulated in Stalnaker and Thomason [83, p. 29] and Stalnaker [82, p. 121] for the case of the similarity relation used in interpreting counterfactuals. Cf. Kolodny and MacFarlane’s treatment of deontic selection functions as “seriously information-dependent” [44, p. 133].

In the terminology from Kolodny and MacFarlane [44, p. 131], this semantics treats deontic ‘ought’ as an “informational modal.” See the Appendix for a concrete way of formalizing the largely theory-neutral analysis presented here within Discourse Representation Theory. For alternative, independently developed accounts, see Björnsson and Finlay [7], Cariani et al. [11], Charlow [13], and Lassiter [49], in addition to the seminal discussion in Kolodny and MacFarlane [44]; though I think there are good reasons for preferring an analysis along the lines presented here, for reasons of space I must reserve discussion for future work.

Examples involving claims about what some other agent ought to do in view of her evidence or claims about one ought to do in view of some other contextually salient body of information—where the agent’s evidence or the salient information differ from the evidence available in the conversational context—pose no special problems and may be treated analogously. In such cases the modal base and the information state to which the preorder is indexed is, intuitively, the one characterizing the agent’s epistemic state or the contextually salient body of information (though see footnote 5).

I am blurring the distinction between global contexts and the (epistemic) modal bases they determine. Given the sort of context-dependence we are interested in, no harm will come from this. For expository purposes I assume that the incrementing proceeds via set-intersection. The point about local interpretation might be put in terms of context change potentials; however, it is ultimately neutral between static implementations (à la Stalnaker) and dynamic implementations (à la Heim), yielding truth-conditions and context change potentials, respectively, as semantic values.

There are several ways of integrating ordering sources into our semantics from Section 5. One option would be to treat g as a function from worlds and information states to sets of propositions; g would be type \(\langle {s, \langle {st, \langle {st, t}\rangle \rangle \rangle }}\). An ordering on worlds could be generated as follows:

-

(i)

\(w' \lesssim _{g(w)(s)} w'' := \forall p \in g(w)(s): w'' \in p \Rightarrow w' \in p\)

-

(i)

For example: “on any setting for the modal base and ordering source standardly considered, the framework fails to predict the [evidence-sensitive] reading on which [(2)] is true”; “the… ordering source runs into a technical problem when it comes to the interaction with conditional antecedents” [11, pp. 14, 34; though see pp. 31–33]. “Standard quantificational semantics for deontic modals… are not able to capture these facts [about information-sensitivity]” [49, p. 136]. Cf. Kolodny and MacFarlane [44, p. 133] and Charlow [13, p. 9]. See also Dowell [16] and von Fintel [22] for discussion.

Cf. Kadmon and Landman [40], von Fintel [20, 21], Lepore and Ludwig [50, pp. 307–311]. More formally:

-

(i)

\(\alpha _{1},\dots , \alpha _{n} \models \beta \) iff for all contexts \(c: \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\alpha _{1}} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c} \cap \dots \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ \alpha _{n} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c} \subseteq \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ \beta \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}\)

It is worth noting that denying an information-sensitive semantics of the sort described in Section 5 won’t allow one to hold on to modus ponens for the indicative conditional—at least if one accepts a Kratzerian restrictor analysis for conditionals: such an analysis doesn’t validate modus ponens anyway (pace suggestions in Dowell [16]). Simple countermodels with and without the postulation of a covert higher modal:

Proof Overt modal restriction: Suppose w 1 is the world of evaluation, \(f(w_{1}) = \left \{w_{1}, w_{2}\right \}\), w 1 is a \((\phi \wedge \psi )\)-world, w 2 is a \((\neg \phi \wedge \neg \psi )\)-world, and \(w_{2} <_{w_{1}} w_{1}\). Then ‘ϕ’ is true (since w 1 is a ϕ-world), and ‘If ϕ, ought ψ’ is true (since w 1, the \(\lesssim _{w_{1}}\)-best ϕ-world in \(f(w_{1})\), is a ψ-world), but ‘Ought ψ’ is false (since w 2, the \(\lesssim _{w_{1}}\)-best world in \(f(w_{1})\), is a \(\neg \psi \)-world). □

Proof Covert modal restriction: Start with the same model as before, but where f (w 1) is the modal base of the covert higher modal. Assume that \( f^{\prime}(w_{1}) \), the modal base of the overt modal at w 1, is {w 1}. Then ‘ϕ’ is true and ‘Ought ψ’ is false for the same reasons as in the first proof; but ‘If ϕ, ought ψ’ is true since for all ϕ-worlds w′ in f (w 1)—namely, w 1—the \(\lesssim _{w'}\)-best worlds in \( f^{\prime}(w') \) is a ψ-world (since w 1 is the only such world w′). □

-

(i)

Compare the notion of a “reasonable inference” in Stalnaker [81], an important inspiration for much work in dynamic semantics. See Willer [95] for elaboration on the importance of a dynamic notion of logical consequence in logics and semantics for information-sensitive deontic modals. A related but importantly different notion is Kolodny and MacFarlane’s notion of “quasi-validity” [44, pp. 139–142]. Roughly, an argument is quasi-valid iff it is (neo)classically valid when its premises are epistemically necessary. As Kolodny and Macfarlane show, modus ponens is quasi-valid. However, as Willer observes (p. 11n.9), a notion of quasi-validity may have more limited importance since it does not apply in hypothetical reasoning and fails to capture certain intuitively valid forms of inference (see also Schulz [74]).

More formally (cf. von Fintel [21, pp. 141–142], Gillies [32, pp. 342–344]):

-

(i)

\(\alpha _{1} , \dots , \alpha _{n} \models _{\mathrm {dynamic}} \beta \) iff for all contexts \(c: \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ \alpha _{1} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c} \cap \dots \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ \alpha _{n} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c|\alpha _{1} | \dots |\alpha _{n-1}|} \subseteq \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ \beta \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c|\alpha _{1} | \dots |\alpha _{n}|}\)

I put this (contentiously) in terms of context change potentials merely for notational convenience. For discussion of various notions of dynamic entailment, see, e.g., Groenendijk and Stockhof [34], van Benthem [4, 5], Veltman [91], Muskens et al. [59].

-

(i)

Discourse referents can be understood as entities that can serve as antecedents for anaphora—introduced non-linguistically or linguistically by indefinite NPs—modeled as constraints on assignment functions. They needn’t correspond with referents in the model. See Karttunen [43] for classic discussion.

I assume a syntacticized version of Kratzer’s semantics for modals, though nothing here hinges on this. Also, our DRSs are merely partial representations, so not all conditions encoding our evidence or the relevant circumstances are given in the representations that follow.

References

Abusch, D. (2012). Circumstantial and temporal dependence in counterfactual modals. Natural Language Semantics.

Atlas, J.D. (1989). Philosophy without ambiguity: A logico-linguistic essay. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bentham, J. (1789/1961). An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Garden City: Doublesday.

van Benthem, J. (1995). Language in action: Categories, lambdas, and dynamic logic. Cambridge: MIT Press.

van Benthem, J. (1996). Exploring logical dynamics. CSLI: Stanford.

Bittner, M. (2001). Topical reference for individuals and possibilities. In R. Hastings, B. Jackson, Z. Zvolenszky (Eds.), Proceedings from SALT XI (pp. 36–55). Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Björnsson, G., & Finlay, S. (2010). Metaethical contextualism defended. Ethics, 121, 7–36.

Brandt, R. (1963). Toward a credible form of utilitarianism. In H.-N. Castañeda (Ed.), Morality and the language of conduct (pp. 107–143). Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Brasoveanu, A. (2007). Structured nominal and modal reference. Ph.D thesis, Rutgers University.

Brennan, V. (1993). Root and epistemic modal auxiliary verbs. Ph.D thesis, Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Cariani, F., Kaufmann, S., Schwager, M. (2011). Deliberative modality under epistemic uncertainty, MS.

Carr, J. (2012). Subjective. ought, MS, MIT.

Charlow, N. (2011). What we know and what to do. Synthese, 1–33.

Coates, J. (1983). The semantics of the modal auxiliaries. London: Croom Helm.

Dowell, J. (2011). A flexible contextualist account of epistemic modals. Philosophers’ Imprint, 11 1–25. http://www.philosophersimprint.org/011014/.

Dowell, J. (2012). Contextualist solutions to three puzzles about practical conditionals. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaethics (Vol. 7). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Eijck, J., & Kamp, H. (1997). Representing discourse in context. In J. van Bentham, & A. ter Meulen (Eds.), Handbook of logic and linguistics (pp. 179–237). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ewing, A. (1953). Ethics. New York: Macmillan.

Finlay, S. (2009). What ought probably means, and why you can’t detach it. Synthese, 177, 67–89.

von Fintel, K. (1999). NPI licensing, Strawson entailment, and context dependency. Journal of Semantics, 16, 97–148.

von Fintel, K. (2001). Counterfactuals in a dynamic context. In M. Kenstowicz (Ed.), Ken Hale: A life in language (pp. 123–152). Cambridge: MIT Press.

von Fintel, K. (2012). The best we can (expect to) get? Challenges to the classic semantics for deontic modals, paper presented at the 2012 Central APA. Symposium on Deontic Modals.

von Fintel, K., & Gillies, A.S. (2008). CIA leaks. The Philosophical Review, 117, 77–98.

von Fintel, K., & Iatridou, S. (2005). What to do if you want to go to Harlem. Anankastic conditionals and related matters, MS, MIT.

van Fraassen, B.C. (1973). Values and the heart’s command. The Journal of Philosophy, 70, 5–19.

Frank, A. (1996). Context dependence in modal constructions. Ph.D. thesis, University of Stuttgart.

Geurts, B. (1995). Presupposing. Ph.D. thesis, University of Stuttgart.

Geurts, B. (2004). On an ambiguity in quantified conditionals, MS. University of Nijmegen.

Gibbard, A. (1990). Utilitarianism and coordination. New York: Garland Publishing.

Gibbard, A. (1990). Wise choices, apt feelings. Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

Gibbard, A. (2005). Truth and correct belief. Philosophical Issues, 15, 338–350.

Gillies, A.S. (2009). On truth-conditions for if (but not quite only if). Philosophical Review, 118, 325–349.

Groefsema, M. (1995). Can, may, must, and should: A Relevance theoretic account. Journal of Linguistics, 31, 53–79.

Groenendijk, J., & Stockhof, M. (1991). Dynamic predicate logic. Linguistics and Philosophy, 14, 39–100.

Hare, R. (1981). Moral thinking: Its levels, method, and point. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Heim, I. (1990). On the projection problem for presuppositions. In S. Davies (Ed.), Pragmatics, (pp. 397–405). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Iatridou, S. (1991). Topics in conditionals. Ph.D thesis, Cambridge: MIT.

Jackson, F. (1986). A probabilistic approach to moral responsibility. In R.B. Marcus, G.J. Dorn, P. Weingartner (Eds.), Logic, methodology, and philosophy of science VII (pp. 351–365). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Jackson, F. (1991). Decision-theoretic consequentialism and the nearest and dearest objection. Ethics, 101, 461–482.

Kadmon, N., & Landman, F. (1993). Any. Linguistics and Philosophy, 16, 353–422.

Kamp, H., Genabith, J., Reyle, U. (2011). Discourse representation theory. In D.M. Gabbay & F. Guenthner (Eds.), Handbook of philosophical logic (Vol. 15, pp. 125–394). Springer.

Karttunen, L. (1974). Presupposition and linguistic context. Theoretical linguistics, 1, 181–194.

Karttunen, L. (1976). Discourse referents. In J. McCawley (Ed.), Syntax and semantics 7: Notes from the linguistic underground (pp. 363–386). New York: Academic Press.

Kolodny, N., & MacFarlane, J. (2010). Ifs and oughts. Journal of Philosophy, cv11(3), 115–143.

Kratzer, A. (1977). What ‘must’ and ‘can’ must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1, 337–355.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H.J. Eikmeyer, & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts. New approaches in word semantics (pp. 38–74). de Gruyter: Berlin.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality/Conditionals. In A. von Stechow, & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research (pp. 639–656). de Gruyter: Berlin.

Kratzer, A. (2012). Conditionals. In Modals and conditionals: New and revised perspectives (pp. 85–108). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lassiter, D. (2011). Measurement and modality: The scalar basis of modal semantics. Ph.D. thesis, New York University.

Lepore, E., & Ludwig, K. (2007). Donald Davidson’s truth-theoretic semantics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leslie, S.-J. (2009). If, unless, and quantification. In R.J. Stainton, & C. Viger (Eds.), Compositionality, context, and semantic values: Essays in honour of Ernie Lepore (pp. 3–30). Springer.

Lewis, D. (1973). Counterfactuals. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1975). Adverbs of quantification. In E. Keenan (Ed.), Semantics of Natural Language (pp. 3–15). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. (1981). Ordering semantics and premise semantics for counterfactuals. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 10, 217–234.

Lyons, J. (1977). Semantics. (Vol. 2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2011). Epistemic modals are assessment-sensitive. In B. Weatherson & A. Egan (Eds.), Epistemic modality (pp. 144–178). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mill, J.S. (1998). In R. Crisp (Ed.), Utilitarianism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moore, G. (1903). Principia ethica. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Muskens, R., van Benthem, J., Visser, A. (1997). Dynamics. In J. van Benthem, & A. ter Meulen (Eds.), Handbook of logic and language (pp. 587–648). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Palmer, F. (1990). Modality and the English modals, 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Palmer, F. (2001). Mood and modality, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Papafragou, A. (2000). Modality: Issues in the semantics-pragmatics interface. Oxford: Elsevier.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parfit, D. (1988). What we together do, MS. Oxford University.

Parfit, D. (2011). On what matters (Vol. I). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Portner, P. (1996). Modal discourse referents and the semantics-pragmatics boundary. In J.C. Castillo, V. Miglio, J. Musolino (Eds.), Maryland working papers in linguistics (Vol. 4, pp. 224–255).

Prichard, H. (1949). Duty and ignorance of fact. In W. Ross (Ed.), Moral obligation, (pp. 18–39). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., Svartvik, J. (1985). A comprehensive grammar of the English language. New York: Longman.

Railton, P. (1984). Alienation, consequentialism, and the demands of morality. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 13, 134–171.

Regan, D. (1980). Utilitarianism and cooperation. Oxford: Clarendon.

van Roojen, M. (2010). Moral rationalism and rational amoralism. Ethics, 120, 495–525.

van Rooy, R. (2001). Anaphoric relations across attitude contexts. In K. von Heusinger & U. Egli (Eds.), Reference and anaphoric relations (pp. 157–181). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Ross, W. (1939). Foundations of ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schulz, M. (2010). Epistemic modals and informational consequence. Synthese, 174, 385–395.

Sidgwick, H. (1907). The methods of ethics, 7th ed. Hackett: Indianapolis.

Silk, A. (2010). Anankastic conditionals in context, MS. University of Michigan.

Silk, A. (2012). Modality, weights, and inconsistent premise sets. In A. Chereches (Ed.), Proceedings of SALT 22 (pp. 43–64). Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Silk, A. (2013). Ought and must: Some philosophical therapy, MS. University of Michigan.

Silk, A. (2013). Truth-conditions and the meanings of ethical terms. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaethics (Vol. 8, pp. 195–222). New York: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1974). Pragmatic presuppositions. In Essays on intentionality in speech and thought (1999) (pp. 47–62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1975). Indicative conditionals. In Essays on intentionality in speech and thought (1999) (pp. 63–77). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1984). Inquiry. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Stalnaker, R., & Thomason, R.H. (1970). A semantic analysis of conditional logic. Theoria, 36, 23–42.

Stephenson, T. (2007). Judge dependence, epistemic modals, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30, 487–525.

Stone, M. (1997). The anaphoric parallel between modality and tense, IRCS TR 97-06, University of Pennsylvania.

Stone, M. (1999). Reference to possible worlds, ruCCS Report 49, Rutgers University.

Swanson, E. (2010). On scope relations between quantifiers and epistemic modals. Journal of Semantics, 27(4), 1–12.

Swanson, E. (2011). On the treatment of incomparability in ordering semantics and premise semantics. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 40, 693–713.

Thomson, J.J. (1986). Imposing risks. In W. Parent (Ed.), Rights, restitution, and risk: Essays in moral theory, (pp. 173–191). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Veltman, F. (1976). Prejudices, presuppositions, and the theory of conditionals. In J. Groenendijk & M. Stokhof (Eds.), Amsterdam papers in formal grammar (Vol. 1, pp. 248–281). Central Interfaculteit: University of Amsterdam.

Veltman, F. (1996). Defaults in update semantics. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 25, 221–261.

Wedgwood, R. (2007). The nature of normativity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wedgwood, R. (2012). Objective and subjective ought, MS. University of Southern California.

Wertheimer, R. (1972). The significance of sense: Meaning, modality, and morality. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Willer, M. (2012). A remark on iffy oughts. Journal of Philosophy, 109, 449–461.

Yalcin, S. (2007). Epistemic modals. Mind, 116, 983–102.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Fabrizio Cariani, Nate Charlow, Jan Dowell, Kai von Fintel, Allan Gibbard, Irene Heim, Angelika Kratzer, Rich Thomason, and audiences at MIT, the 2011 ESSLLI Student Session, and the 2012 Central APA deontic modals session for helpful discussion, and to anonymous reviewers from ESSLLI and the Journal of Philosophical Logic for their valuable comments. Thanks especially to Eric Swanson for extensive discussion and detailed comments on previous drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Evidence-Sensitivity in DRT

Appendix: Evidence-Sensitivity in DRT

I have argued that deontic preorders used in interpreting ‘ought’ can be sensitive to what the modal base is like and how it is updated locally. Since Discourse Representation Theory (DRT) has been enormously fruitful in its treatment of sentence-internal context updates, in this appendix I will formalize the more theory-neutral analysis of information-sensitivity from Section 5 using DRT. Of course there will be alternative implementations.

1.1 DRT: Some Background

A Discourse Representation Structure (DRS) represents the body of information accumulated in a discourse. A DRS consists of a universe of “discourse referents” (objects under discussion), depicted by a set of variables, and conditions that encode information gathered in the discourse.Footnote 28 Syntactically, algorithms map syntactic structures onto DRSs. Semantically, DRSs are interpreted model-theoretically by embedding functions—functions from discourse referents to individuals in a model such that for each discourse referent x, the individual that x is mapped onto has every property associated with the conditions on x. Truth is then defined at the discourse level rather than at the sentence level: roughly, a DRS K is true in a model \({\mathcal {M}}\) iff there is an embedding function for K in \(\mathcal {M}\) that verifies all the conditions in K. Different types of conditions have different verification clauses (see below).

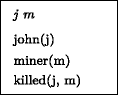

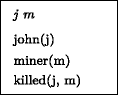

A simple example should clarify. Take the single-sentence discourse ‘John killed a miner’. The following DRS represents the information that there are two individuals—John and a miner—and that the first killed the second.

-

(26)

f verifies (26) in a model \(\mathcal {M}\) iff the domain of f includes j and m, and according to \(\mathcal {M}\), f (j) is John, f (m) is a miner, and f (j) killed f (m). Roughly, the DRS (26) is true in a model \(\mathcal {M}\) iff there is an embedding function in \(\mathcal {M}\) that verifies all its conditions—here, iff there is an embedding function in \(\mathcal {M}\) such that j can be mapped onto an individual in the model, John, and m can be mapped onto an individual which is a miner in the model, such that the individual corresponding to j killed the individual corresponding to m. The universe of this DRS is {j,m} and the condition set is {John(j), miner(m), killed(j,m). This DRS forms the background context against which subsequent utterances are interpreted.

Modally quantified sentences induce more complex DRSs. For concreteness, I will follow the DRT analysis of modals in Frank [26]. As contexts are often represented in dynamic theories of interpretation in terms of sets of states—sets of world-embedding function pairs \(\langle {w, e}\rangle \)—Frank, following Geurts [27], introduces context referents that denote such sets.Footnote 29 Update conditions \(G:: F + K'\), from an input context referent F with a DRS K′ to an output context referent G, are used to represent the dynamic meaning of sentences in a discourse. A bit of terminology:

Definition 9

A Discourse Representation Structure (DRS) K is an ordered pair \(\langle {U_{K} = U_{K_{\mathrm {ind}}} \cup U_{K_{\mathrm {cont}}}, Con_{K}}\rangle \), where \(U_{K_{\mathrm {ind}}}\) is a set of variables, \(U_{K_{\mathrm {cont}}}\) a set of context referents, \(U_{K}\) the universe of K, and \(Con_{K}\) a set of conditions.

Definition 10

An embedding function f for K in an intensional model \(\mathcal {M}\) is the union of an embedding function f 1 and an embedding function f 2, where:

-

1.

f 1 for K in \(\mathcal {M}\) is a (possibly partial) function from \(U_{K_{\mathrm {ind}}}\) into D.

-

2.

f 2 for K in \(\mathcal {M}\) is a (possibly partial) function from \(U_{K_{\mathrm {cont}}}\) into sets of states \(\langle {w, f_{1}}\rangle \).

For embedding functions f and g and DRS K, g extends f with respect to K—written ‘\(f[K]g\)’— iff \(Dom(g) = Dom(f) \cup U_{K}\) and \(f \subseteq g\).

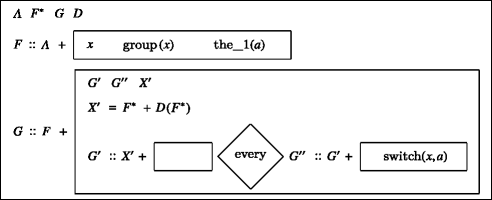

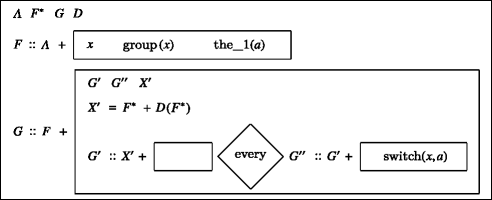

A modal’s nuclear scope—the DRS representing its prejacent—is treated as anaphoric to an antecedent context referent that is updated with the restrictor. (This is intended to capture, among other things, Kratzer’s notion of relative modality.) This anaphoric analysis yields the following general logical form for modals Q (depicted with a diamond) in (27), relative to an anaphoric context referent X′, restrictor DRS K′, scope DRS K″, and context referents G′ and G″.

-

(27)

There are a number of ways to render the computation of the modal’s domain of quantification information-reflecting. Here I will do so by treating the denotation of a deontic context referent D as a function from a set of worlds (an information state) to a set of states, those states consistent with what is deontically required in view of that information state. For ease of exposition I abstract away from details involving Kratzer’s ordering source and treat a deontic modal’s modal base as complex, consisting of a merged context R + D, where R is the relevant “realistic” (circumstantial, epistemic) context. Specifically, I assume that the complex modal base B is formed from the merge of a realistic context R and a deontic context D that takes R as argument: \(B = R + D(R)\). The denotation of B determines the set of worlds \(\sigma (e(B)) = \sigma (e(R)) \cap \sigma (e(D)(e(R)))\)—i.e., the set of worlds consistent with the relevant body of facts or evidence and what is deontically required relative to the information state determined by that body of facts or evidence. The set of worlds (“context set”) \(\sigma (\Gamma )\) determined by a set of states \(\Gamma \) is given as follows:

Definition 11

\(\sigma (\Gamma ) = \{w' : (\exists x')\langle w', x'\rangle \in \Gamma \}\), for a set of states \(\Gamma \)

Some relevant verification conditions (see, e.g., Frank [26], van Eijck and Kamp [17], Kamp et al. [41] for fuller treatments):

Definition 12

For all worlds w, (well-founded) embedding functions e, f, g, h with domains in U K , intensional models \(\mathcal {M}\), DRSs K, K′, K″, and sets of conditions Con:

-

1.

The truth-conditions of a DRS K in \(\mathcal {M}\):

-

(a)

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {K} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] _{\langle {w,f} \rangle } = \left \{\langle w, g\rangle : f[K] g\ \&\ \langle w, g\rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} K\right \}\)

-

(b)

A DRS K is true in \(\mathcal {M}\) iff \(\exists f : \langle w, f\rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} K\)

-

(a)

-

2.

The context change potential of a DRS K in \(\mathcal {M}\) w.r.t input and output states \(\langle {w, f}\rangle , \langle {w, g}\rangle :\)

\({_{\langle {w, f}\rangle }\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {K} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] _{\langle {w, g} \rangle }}\) iff \(f\left [K\right ]g\ \&\ \langle w, g \rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} K\)

-

3.

Verification of a DRS K in \(\mathcal {M}\) by embedding function e:

\(\langle w, e\rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} \langle K \rangle \) iff \(\exists f : e[K]f\ \&\ \forall c \in Con_{K} : \langle w, f\rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} c\)

-

(a)

\(\langle w, e\rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} P^{n}(x_{1},\dots ,x_{n})\) iff \(\langle e(x_{1}),\dots ,e(x_{n})\rangle \in I(P^{n})\)

-

(b)

\(\begin{array}{rll} \langle w', e\rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} G:: F + \langle K'\rangle \mbox { iff } e(G) = \{\langle w', g\rangle \,:\, \exists \langle w', f\rangle \in \\ e(F) \mbox { s.t.\ }{_{\langle {w', e \cup f} \rangle }\left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {K} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] _{\langle {w', g}\rangle }}\}\ \&\exists \langle w, g\rangle \in e(G) \end{array}\)

-

(c)

\(\langle w, e\rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} G:: X' + \langle K'\rangle\ \Diamond _{\mathrm {every}}\ H:: G + \langle K''\rangle \) iff

\(e(G) = \{\langle w', g\rangle : \exists \langle w', x'\rangle \in e(X') \mbox { s.t.\ } {_{\langle {w', e\cup x'} \rangle }\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {K} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] _{\langle {w', g} \rangle }}\}\ \&\)

\(e(H) = \{\langle w', h\rangle : \exists \langle {w', g}\rangle \in e(G) s.t.\ {_{\langle {w', e\cup g} \rangle }\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {K} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] _{\langle {w', h}\rangle }}\ \&\)

\(\qquad\qquad \forall \langle w', g\rangle : \langle w', g\rangle \in e(G) \to \exists \langle w', h\rangle \in e(H)\}\)

-

(d)

\(\langle w, e\rangle \models _{\mathcal {M}} G = F + D(F)\) iff

\(e(G) = \{\langle w', g\rangle{\kern2pt}\,:{\kern-2pt}\exists \langle w', f\rangle \in e(F)\ \exists \langle w', d\rangle \in e(D)(e(F))\) s.t.

\(\langle w', g\rangle = {\langle {w', f \cup d}\rangle }\}\)

-

(a)

1.2 The Data

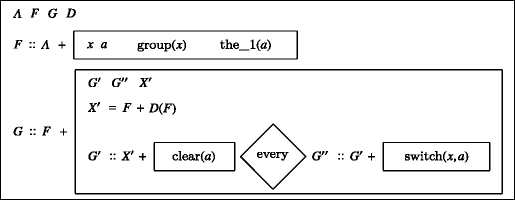

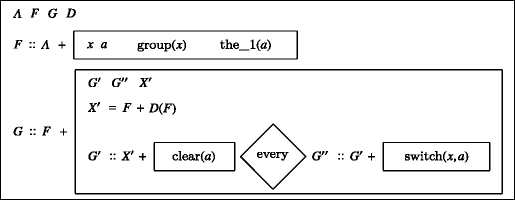

Turning to our data, first let’s analyze (2), our evidence-sensitive unembedded deontic ‘ought’. The (partial) DRS for (2) will be roughly as in (28). Let F be the context that encodes our evidence; D encode what is deontically required; and \(\Lambda \) be the empty context that begins the discourse, where \(e(\Lambda ) = \{\langle {w', \lambda }\rangle : w' \in W\}\) and \(\lambda \) is the empty function.Footnote 30

-

(28)

We ought to stay put.

The left-hand subordinate box is empty since the modal’s domain is already restricted by virtue of being anaphoric to the prior context F. Importantly, what is deontically required anaphorically depends on the realistic context F. The complex modal base \(X' = F + D(F)\) restricts the modal’s domain of quantification to worlds that are consistent with the available evidence and what is deontically required relative to this evidence—i.e., to worlds in \(\sigma (e(F)) \cap \sigma (e(D)(e(F)))\). Accordingly (28) is true iff in all of these worlds, we stay put. More generally, the modal condition in the DRS updating F is verified iff every state in the denotation of X′ can be extended to a state that verifies the scope DRS . Since the deontic context is sensitive to what the epistemic context is, this modal condition is indeed verified.

. Since the deontic context is sensitive to what the epistemic context is, this modal condition is indeed verified.

Now reconsider our circumstantial ‘ought’ in (4). The DRS for (4) will be much like that in (28); however, the modal’s restriction will be anaphoric, not to F, but to \(F^*\), a context referent that encodes the relevant facts about the situation.

-

(29)

We ought to switch to the 1.

So the context set of the denotation of \(F^*\) includes only worlds where the 1 is clear. Since the deontic context D is sensitive to this, the modal condition, evaluated with respect to the complex modal base \(X' = F^* + D(F^*)\), is verified. We switch to the 1 in all worlds in the context set of the denotation of X′—i.e., all worlds in \(\sigma (e(F^*)) \cap \sigma (e(D)(e(F^*)))\).

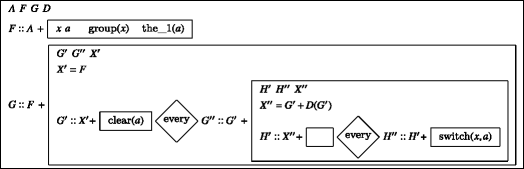

Turning to (7), in order to capture how the ‘ought’ is interpreted with respect to its local context, we need to ensure that the deontic context merges with the updated modal base that includes the condition encoded by the ‘if’-clause in forming the modal’s complex modal base. So, the DRS in (30) will not provide the correct representation of (7).

-

(30)

If the way is clear, we ought to switch to the 1.

The problem is that the complex modal base \(X' = F + D(F)\) is formed before the context is updated with the restrictor DRS .

.

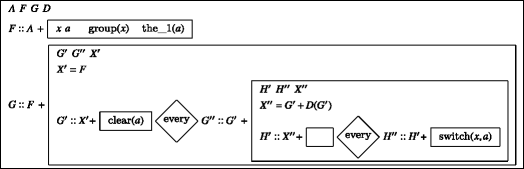

So, if we are to correctly represent the intended readings of deontic conditionals like (7) within our current semantic framework, we may need to posit a covert necessity modal that scopes over, and is restricted by, the ‘if’-clause. (Alternative frameworks may not require this move.) As briefly mentioned in Section 4, such a move has much independent support—e.g., in light of data with anankastic conditionals, nominally quantified ‘if’- and ‘unless’-sentences, and ‘might’-counterfactuals—though, for reasons of space, I will not rehearse those arguments here (see n. 14). Suffice it to say that this independently motivated element helps yield the accurate representation of (7) in (31).

-

(31)

If the way is clear, we ought to switch to the 1.

The modal base X′ of the covert modal is anaphoric to the context referent F that encodes the available evidence (see Sections 4–5). The complex modal base X″ of the overt deontic ‘ought’ is identified with the update of X′ with the DRS representing the ‘if’-clause merged with the deontic context—i.e., \(X'' = G' + D(G')\). Crucially, this allows the information-sensitive deontic context D to interact with the context referent G′ that encodes the condition that the way is clear, rather than with F, which does not. So the embedded ‘ought’ quantifies over worlds in which the way is clear that are consistent with the evidence and what is deontically required relative to this updated information state. Accordingly, the modal condition in G is verified; we switch to the 1 in all worlds in \(\sigma (e(X''))\).

Finally, a brief word about the ‘even if’ conditional in (9). Independent considerations from Frank [26] suggest that in modalized ‘even if’ conditionals, the embedded modal’s modal base is anaphoric to the non-updated context referent X′ = F, rather than to the updated context G′ as in (31)—in Kratzerian terms, to the higher modal’s modal base f (w) rather than to \(f^{+}(w)\). This is represented in (32).

-

(32)

Even if the way is clear, we ought to stay put.

If this view on ‘even if’ conditionals is right, we have an independently motivated way of predicting the appropriate truth-conditions for (9). As in (28), what is deontically required is calculated relative to the non-updated information state that encodes our actual evidence.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Silk, A. Evidence Sensitivity in Weak Necessity Deontic Modals. J Philos Logic 43, 691–723 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-013-9286-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-013-9286-2