Abstract

Policy-makers involved in cybersecurity governance should pay close attention to the ‘generative metaphors’ they use to describe and understand new technologies. Generative metaphors structure our understanding of policy problems by imposing mental models of both the problem and possible solutions. As a result, they can also constrain ethical reasoning about new technologies, by uncritically carrying over assumptions about moral roles and obligations from an existing domain. The discussion of global governance of cybersecurity problems has to date been dominated by the metaphor of ‘cyber war’. In this paper, I argue that this metaphor diminishes possibilities for international collaboration in this area by limiting states to reactive policies of naming and shaming rather than proactive actions to address systemic features of cyberspace. We suggest that alternative metaphors—such as health, ecosystem, and architecture—can help expose the dominance of the war metaphor and provide a more collaborative and conceptually accurate frame for negotiations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The debate on the regulation of international ‘cyber warfare’ is a negotiation over the assignment of moral obligations. Consider the example of the WannaCry ransomware attack, which affected more than 200,000 computers across 150 countries, with total damages estimated at billions of dollars (Berr 2017). In this case, a hacking group—attributed by the US and UK governments to North Korea—targeted a vulnerability in the Microsoft Windows operating system. The vulnerability had been discovered by the US National Security Agency (NSA) but not disclosed to the public (Collier 2018). A hacking group named the Shadow Brokers stole the vulnerability from the NSA and released it online, making the WannaCry attack possible.

In this complex web of actors and cyber intrusions, whom do we blame for the billions of dollars of damage and impaired functionality in crucial services like hospitals? Is it just the hacking group behind the attack? or the US government, which did not disclose a potentially dangerous vulnerability? or Microsoft, for creating software with vulnerabilities? or the hundreds of organisations—including hospitals—and users who did not update their systems with the patch that Microsoft released to address the problem? These are pressing questions, as their answers point to which actors carry the responsibility for ensuring global cybersecurity. Existing attempts to address them by developing norms of conduct for cyber conflict—such as the United Nations Governmental Group of Experts (UN GGE) or the Tallinn Manual—have largely stalled and left them unresolved (Grigsby 2017).

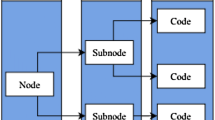

Imagine a new group of national negotiators coming together to address risks posed by information and communication technologies (ICTs).Footnote 1 Such a group would need to make several critical decisions before formal negotiations began. These might include the venue (UN GGE or elsewhere?), number of states (small circle of like-minded states or broad inclusiveness?) and the nature of stakeholders (private sectors and or NGOs representatives?). However, this group should also consider an underlying and often overlooked question: which metaphors will structure the negotiating process? In this paper, I focus on the generative power of metaphors and their impact in policy-making. ‘Generative metaphors’ prescribe new solutions to policy problems through a process of reconceptualisation (Schön 1979). In particular, I address the case of cybersecurity and analyse the impact, limits and advantages of four metaphors in this area, namely: war, health, ecosystem and infrastructure.

Metaphors constrain ethical reasoning, leaving us to assume, sometimes uncritically, a certain framework to define the moral scenario and ascribe responsibilities (Thibodeau and Boroditsky 2011). When this happens, applying an alternative metaphor can open up space for new thinking. To date, efforts to create norms for international cybersecurity have been dominated by the metaphor of war. While this metaphor may be useful for addressing some malicious uses of ICTs, it is not optimal to frame and understand them in all circumstances. As I argue in this paper, the metaphor diminishes possibilities for international collaboration in this area by limiting states to reactive policies of naming and shaming rather than proactive actions to address systemic features of cyberspace.

In this paper, I distinguish between ‘metaphors’ and ‘analogies’ and outline relevant existing literature on their role in cognition and ethical reasoning. I then analyse extant literature on metaphors in cybersecurity policy and argue that they fail to incorporate insights from cognitive linguistics. Lastly, I compare four metaphors in this policy area and adapt Lukes’ (2010) technique for exploring clashing metaphors to foster innovative thinking on policy problems posed by ICTs.

2 Metaphors and Analogies

Metaphors are often defined as either describing or understanding one thing in terms of another. This difference hints at a complex debate regarding the role of metaphor in thought. Until the 1970s, metaphors were commonly seen as a matter of poetry or rhetoric (Lakoff and Johnson 1980). In this view, metaphors are essentially epiphenomenal: they merely describe beliefs that exist prior to the speaker’s use of metaphor but do not influence the speaker’s thinking. In contrast, proponents of conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) argue that metaphors are central to human cognition and have a causal role in partially determining an agent’s judgements or choice behaviour (Lakoff and Johnson 1980).

According to CMT, metaphorical expressions are ‘surface realisations’ of underlying cognitive processes in which the source domain ‘structures’ the target domain. For example, Lakoff and Johnson posit that our understanding of ideas (target) is metaphorically structured by food (source). As evidence for this structure, they provide dozens of ‘linguistic’ metaphors, such as ‘He’s a voracious reader’ or ‘We don’t need to spoon-feed our students’ (Lakoff and Johnson 1980, pp. 47–48).

The extent to which linguistic metaphors reflect underlying conceptual structures is still disputed. As Black (1993) points out, this disagreement is exacerbated by the fact that opponents tend to pick relatively trivial metaphors. Following Black, I focus on metaphors that are commonly in use, ‘rich’ in background implication, and ‘strong’ in the sense that they create a more powerful link than a mere comparison. In Black’s account, strong metaphors lead us to ‘see’ A as B; for example asserting seriously that ‘The Internet is a drug!’ is (at least) to think of the Internet as a drug. Strong metaphors are therefore constitutive, as they create mental models for what they describe.

This understanding informs our proposed distinction between metaphor and analogy. An analogy is a comparison between two objects, concepts or phenomena. As an ideal type, an analogy is carefully elaborated to note both similarities and dissimilarities between source and target to further understanding. Metaphors are based on analogies, but they go further by asserting that A is B.

Constitutive metaphors are useful to understand new phenomena, like cyber conflicts. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) argue that to name and make sense of intangible or unprecedented experiences, I categorise the world through metaphors. Johnson (1993) maintains that a similar process of ‘moral imagination’ underlies moral reasoning: we use metaphors to apply existing ethics to new situations. Because of their constitutive power, metaphors carry over associations and assumptions about roles and obligations from one realm to another.

The same process occurs when considering legal approaches to new technologies, as legal precedent works through analogy (Gill 2017). For example, the legal metaphors of text, speech and machine for computer code each suggest a different legal regime for regulating code (Vee 2012). When faced with problems posed by new technologies, the first response is to ‘explain why the new technology can be treated identically to an earlier technology’ (Froomkin 1995, cited in Wolff 2014, p. 2). Consequently, Wolff (2014) argues that the field of Internet law is particularly adept at assessing metaphors and understanding their deterministic role.

3 Metaphors in Cybersecurity Policy

In contrast, existing research on cybersecurity metaphors tends to approach metaphors disparagingly: they often identify cybersecurity metaphors, analyse their strengths and limitations, and then implore the reader to use metaphors carefully, if at all. Lapointe (2011, p. 18) identifies ‘ecosystem’, ‘public health’, ‘battlefield’, ‘global commons’ and ‘domain’ and then states: ‘substantive discussion of the way ahead depends on our ability to leaven our literal discourse with a dash of metaphor rather than the other way around’. Betz and Stevens (2013, p. 14) ‘interrogate’ metaphors of ‘space’ and ‘health’, which ‘channel us into a winner-takes-all modality’ and suggest that we should avoid the dominant metaphors and seek out ‘positive-sum formulations’. Wolff discusses the metaphors of the ‘burglar’, ‘war’ and health and concludes that it is ‘far too late … to try to rein in the metaphorical language surrounding computer security issues’; however it is ‘possible that the most productive ways of discussing them are [ …] those most resistant to metaphoric thinking’.

These approaches share three limitations. They pick illustrative examples of metaphors in political speech or suggest hypothetical ones, but do not systematically assess actual policies or policy proposals. They warn against metaphors and call for more literal language, without offering any suggestions for language which might replace the metaphors that they complain of. Sauter’s (2017) analysis offers a partial exception, as she considers policy documents on Internet regulation and suggests an alternative metaphor of ‘global commons’, although she does not elaborate the implications of using this metaphor in Internet regulation. All these analyses are further limited by the lack of a precise explanation of metaphors. This ambiguity can lead theorists to understate their importance. For example, Shimko’s (1994, p. 665) paper on metaphor in foreign policy decision-making states that analogies ‘offer concrete policy guidance’ while metaphors ‘provide an underlying intellectual construct for framing the situation’ but do not have ‘direct implications in terms of formulating and selecting foreign policies’.

In contrast, Schön’s (1979) work on generative metaphors highlights the interdependence between framing and formulating policy. Such metaphors generate new solutions to problems through reconceptualising them. Schön uses the memorable example of a group of engineers attempting to design a synthetic brush who are flummoxed by the uneven, ‘gloppy’ strokes of their designs. Suddenly, one of them exclaims ‘You know, a paintbrush is a kind of pump!’ This metaphor calls the engineers’ attention to the spaces in between the bristles, through which paint flows, resulting in a far more successful design.

Schön (1979) argues that metaphors play a similar role in prescribing policy. Policy analysis is often understood as a form of problem-solving, where the problems themselves are assumed to be given. However, problems are not given, but ‘constructed by human beings in their attempts to make sense of complex and troubling situations’. For example, understanding low-income neighbourhoods as a ‘disease’ vs. a ‘natural’ community has direct implications for policy choice in the issue of housing, as each of these metaphors carry a normative judgement about what is ‘wrong’ and what needs fixing (Schön 1979).

Schön proposes that policy is better understood as a matter of ‘problem-setting’. Many conflicting policy solutions are traceable to this process of problem-setting, which encompasses the metaphors underpinning the problem framing. These metaphors are generative and define a mental model of the problem that makes certain policy solutions appear natural or appropriate.

With this expanded conceptual toolkit, we can now return to the subject of cybersecurity. The rise of ‘cyber’ neologisms stems from the need to find words to describe new socio-technical phenomena. Most, if not all, cyber-words have a metaphorical element, as they assign new phenomena to existing conceptual categories. This is a crucial aspect to consider in discussions of ‘cyber war’. For the choice of the topics to debate, the trades-off to define, the space of possible solutions, and the posture of the actors involved in the discussion are determined by the war metaphor.

4 Cyber War: Description or Mere Metaphor?

One of the most prominent articles on cyber war denies its existence:

‘Cyber war has never happened in the past. Cyber war does not take place in the present. And it is highly unlikely that cyber war will occur in the future’. (Rid 2012)

Referencing military theorist von Clausewitz, Rid (2012, p. 8) suggests that for an offensive act to qualify as an act of war, it must meet three necessary conditions: ‘it has to have the potential to be lethal; it has to be instrumental; and it has to be political’. Following an analysis of offensive acts that are sometimes described as cyber war—like the 2007 DDoS attacks on Estonia or the 2010 Stuxnet attack on Iranian centrifuges—Rid (2012, p. 9) argues that no cyber attacks to date have fulfilled these conditions. He concludes that the “‘war’ in ‘cyber war’ has more in common with the ‘war’ on obesity than with World War II—it has more metaphoric than descriptive value”.

Rid proposes a ‘more nuanced terminology’ as an alternative (Rid 2012). Past and present cyber attacks are ‘merely sophisticated versions of three activities that are as old as warfare itself’, namely: subversion, espionage, and sabotage. He argues that using these terms will allow policy makers and theorists to gain greater clarity in discussions of cyber attacks.

However, the distinction that Rid makes between ‘descriptive’ and ‘merely metaphorical’ is confusing, as metaphors are descriptive. As I outlined in Sect. 1, (strong) metaphors generate mental models that carry over associations from one domain to another. Discussions of cyber war also include cyber weapons, bot armies and virtual arsenals. In describing cyber conflicts as a war, these metaphors extend the conceptual category of war to encompass meaningfully cyber operations and define a set of ‘obvious’ solutions (Schön 1979). Indeed, to date, the conceptual framework of war has shaped almost all initiatives seeking to create international cybersecurity policy.

The UN Governmental Group of Experts (GGE) process, which lasted from 2005 to 2016, started as a ‘cyber arms control’ treaty within the UN General Assembly ‘First Committee’ for disarmament and ‘politico-military’ security (Maurer 2011). Although the arms control approach was never realised, the later stage of negotiations sought to apply solutions from another branch of the laws of war, namely international humanitarian law (IHL), which sets out ‘taboo’ targets such as non-combatants or prisoners of war (Grigsby 2017; J. Nye 2017). In the same vein, The Tallinn Manual—commissioned by the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence—explicitly applies existing laws of war to cyber conflict by interpreting the legal thresholds of ‘use of force’ and ‘armed attack’ used in the UN Charter (Dev 2015). All these solutions draw on regulatory frameworks developed for conventional kinetic (i.e. violent) war, because cyber conflict is conceptualised as a kind of war.

Rid’s paper seeks to counter cyber war’s constitutive effect through criteria and precise language. Yet, conceptual categories are rarely defined by the kind of rigid criteria that Rid imposes on the concept of war. Studies in cognitive linguistics show that categories operate by prototypes rather than necessary and sufficient criteria (see Lakoff 1991 for a review). When categorising a phenomenon, we assess its similarity to the prototype through gradations of ‘fit’ rather than clear criteria. The prototypical war—in the Western imagination—is a lethal confrontation between armies directed by nation states, complete with explosions, blood, and guts.Footnote 2 The war on obesity is far removed from the prototypical war as it involves neither clashing nation-states nor armies; while World War II fits the concept of war perfectly. It is only by ignoring wars like the Cold War, the War on Terror, or trade wars that Rid’s paper manages to present war as a category with clear boundaries.

As I explained in the previous section, cyber-words have a metaphorical element, as they assign new phenomena to existing conceptual categories. Dismissing the use of cyber war as ‘merely metaphorical’ is also dismissing the ubiquity and necessity of this categorisation. For example, the nuanced terminology, like ‘cyber espionage’, that Rid suggests as an alternative to cyber war is also arguably metaphorical.

In his history of the terminology used by US intelligence officials for state-sponsored hacking, Jones (2017) points out that the doctrinal category of Computer Network Exploitation (CNE) only emerged in 1996:

“With this new category, ‘enabling’ was hived off from offensive warfare, to clarify that exploiting a machine—hacking in and stealing data—was not an attack […]. The new category of CNE subdued the protean activity of hacking and put it into an older legal box—that of espionage’. (Jones 2017, p. 15)

Espionage, unlike warfare, is necessary, ubiquitous, and—crucially—entirely unregulated by international law. Therefore the unregulated legal status of government hacking relies on the metaphor of espionage. Jones criticises this ‘disanalogy with espionage’: state-sponsored hacking is significantly different from traditional espionage due to the extreme ease and scale of information exfiltration, as well as the fact that the techniques of cyber espionage and cyber attack are often identical (Brown and Metcalf 1998, p. 117, cited in Jones 2017, p. 15). Jones argues:

“‘Enabling’ is the key moment where the analogy between traditional espionage and hacking into computers breaks down … The enabling function of an implant placed on a computer, router, or printer is the preparation of the space of future battle: it’s as if every time a spy entered a locked room to plant a bug, that bug contained a nearly unlimited capacity to materialize a bomb or other device should distant masters so desire.” (Jones 2017, p. 20)

The fact that state-sponsored hacking does not fit easily within the conceptual category of espionage suggests that Rid’s suggested use of cyber espionage can also be understood as metaphorical. The disanalogy of cyber espionage also illustrates a critical point: conceptual categories are not ‘fixed’ but socially constructed, sometimes with strategic intent.

One way in which these categories are constructed is when foreign policy analysts assert the relevance of a certain metaphor because it is in the same ‘general realm of experience’—to use Shimko’s (1994) phrase. A powerful example is an edited volume titled Understanding Cyber Conflict: 14 Analogies. The volume ‘explores how lessons from several wars since the early nineteenth century, including the World Wars, could apply—or not—to cyber conflict in the twenty-first century’ in 14 chapters grouped around questions like: ‘What Are Cyber Weapons Like?’ and ‘What Might Cyber Wars Be Like?’. Following the distinction I made in Sect. 2, these chapters use analogies as explicit comparisons between the domain of cyber conflict and the domain of kinetic warfare. However, none of the 14 chapters looks to conflicts outside the realm of war, ignoring, for example, conflictual dynamics existing in trade or environmental negotiations. This both stems from and reinforced the underlying constitutive metaphor which leads researchers and policy-maker to see cyber conflict as a kind of war.

Consequently, although Rid’s article clearly articulates the inaccuracies of describing cyber conflict as a war, his proposed solution has two problems. Firstly, it understates, and therefore underestimates, the constitutive effect metaphors have in generating entire mental models. Secondly, it fails to consider that the proposed, supposedly clean and analytical language, is also metaphorical, and therefore carries over its own assumptions about roles, responsibilities, and regulatory models. The question of whether we can ever escape metaphorical language is hotly contested in the philosophy of language (see Eco and Paci 1983) and largely outside of the scope of this paper.

However, as Gill (2017) and others point out, as information is formless, metaphorical language is particularly common in law and policy related to the digital environment. Therefore, precise language is insufficient to address metaphorical reasoning, particularly as it is likely that new expressions will also be metaphorical. New concepts—such as Kello’s (2017) use of ‘unpeace’ to describe the ambiguous, constant conflict below the threshold of war—offer one way to address this conceptual puzzle. However, if we use ‘unpeace’ instead of war, but still think in terms of arms control, armies, and laws of war, the underlying war metaphor will still structure our thinking. Instead, we should seek out ways to expose how deeply our thinking on cyber conflict is entrenched in the conceptual category of war. This in turn will allow us to identify more constructive metaphors for analysing cyber conflict.

In the following section, I elaborate a method for policy-makers and researchers to critically assess policy metaphors: first, identify metaphors which structure the regulation of new technologies, particularly cases where this structure is problematic; second, seek out other metaphors which might be applied to the same policy area; third, by contrasting these competing metaphors, generate a wider variety of potentially useful policies and regulatory approaches.Footnote 3

5 Comparing Metaphors

To illustrate how metaphors shape ethical reasoning, the following sections will discuss the roles and obligations suggested by four metaphors in cybersecurity governance, these are the metaphors of war, health, ecosystem and infrastructure.

5.1 War

As I outlined in the previous section, most existing norm initiatives—including the UN GGE, the Tallinn Manual, and the Digital Geneva Convention—have relied on the conceptual framework of war. The war metaphor is appealing both because the laws of war are one of the most developed and well respected international regulatory regimes and because cyber conflict holds many similarities to war (Schmitt and Vihul 2014). However, the inevitable focus on attributing attacks and punishing wrong-doers steers foreign policy on a reactive cycle of ‘naming and shaming’, which is further complicated by the politics and uncertainties of attribution. War also implies a zero-sum politics in which states are solely responsible to their own citizens, which ignores systemic and structural causes of cyber conflict, such as the worldwide spread of insecure ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT) devices which can be co-opted for DDoS attacks.

Problems with the regulatory model of war can be divided into conceptual and practical ones. The conceptual difficulties have been described in depth elsewhere (Rid 2012; Taddeo 2016, 2017), and so they will be only briefly summarised here. The existing laws of war are built on the tenet of ‘war as a last resort’. In contrast, cyber attacks are ubiquitous and (mostly) non-violent (non-kinetic). Most cyber operations, such as DDoS attacks, cause temporary losses of functionality rather than permanent destruction. Therefore, approaches to the regulation of state-run cyber attacks that rely on International Humanitarian Laws (IHL)—for example, the Tallinn Manual’s—leaves unaddressed the vast majority of existing and potential incidents which do not cause physical destruction (Taddeo 2016).

Furthermore, cyber conflicts involve a variety of state and non-state actors in often ambiguous relationships of dependency and antagonism. This poses a problem as the conceptual framework of war relies on clearly defined state antagonists. Ambiguity around actors and motives involved in cyber attacks complicates the problems of attribution and proportionality (Taddeo 2017; Taddeo and Floridi 2018). Even in cases where an attack is traced to a particular national territory, the precise nature of a state’s involvement—whether it coordinated, facilitated, or merely turned a blind eye to an attack by “patriotic hackers—often remains obscure. This makes it difficult to calculate what a ‘proportional’” response should be.

These conceptual shortcomings underlie a set of practical problems created using the metaphor of war. The adversarial framing has complicated international negotiations. This is evident in the break-down of the UN GGE negotiations, the longest running effort to create norms for cyber conflict. The widely acknowledged cause for this rupture was the opposition by Russia, China, and Cuba to the US/UK insistence on confirming the applicability of the right to self-defence and IHL to cyberspace (Grigsby 2017; Korzak 2017; Lotrionte 2017). The opposing nations argued the right to self-defence would link cyber conflict to kinetic conflict in a way that favours the stronger military powers. As the Cuban expert declaration explains, the application of IHL ‘would legitimize a scenario of war and military actions in the context of ICT’ (Rodríguez 2017).

The language of war, which continually reintroduces the largely incompatible understandings of ‘information warfare’, likely exacerbated this worry. In the Anglosphere, both ‘cybersecurity’ and ‘information security’ are technical terms referring to the ‘preservation of the confidentiality, availability and integrity of information in cyberspace’ (Giles and Hagestad II 2013). However, within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), China and Russia among others have solidified a contrasting regional understanding based on the notion of an ‘information space’, which includes information in human minds. Intrusions such as psychological operations or ‘information weapons’ aimed at ‘mass psychologic brainwashing to destabilise society and the state’ may threaten a state’s information security (SCO 2009, p. 209). This is evident in Cuba’s GGE submissions, which repeatedly denounce the ‘aggressive escalation’ of the USA’s ‘radio and television war against Cuba’ alongside other hostile uses of telecommunications (UNGA 2015, 2016, 2017).

This contrasting use of spatial metaphors—global ‘cyberspace’ vs. national ‘information space’—lies at the heart of the UN GGE disagreement. Western states wished to focus on information architecture rather than content, and feared that Russia’s new treaty could be used to limit free speech under the guise of increasing information security (Maurer 2011; McKune 2015).

The Tallinn Manual and the UN GGE limited themselves by approaching cybersecurity as a matter of war—both explicitly, in trying to apply IHL, and implicitly, by negotiating within fora for arms control and focusing on taboos for targets. Underlying both the conceptual and practical difficulties outlined in this section is a set of ethical assumptions reinforced by the war metaphor. War implies a zero-sum mentality for states, in which their primary responsibility is to punish attackers and defend their own security and that of their own citizens. Wider or more cooperative notions of responsibility are easily overshadowed.

Debates about the concept of cyber war have gone on for several years now, to the extent that it may seem gratuitous to catalogue the problems with this metaphor now. However, despite many criticisms of the concept—including but not limited to Rid (2012); Betz and Stevens (2013); Wolff (2014); Taddeo (2016)—many contemporary policy framings continue to rely on this underlying metaphor. For example, the more recent ‘Digital Geneva Convention’ suggested by Microsoft adopts IHL principles and proposes a neutral verification body similar to the ‘role played by the International Atomic Energy Agency in the field of nuclear non-proliferation’ (Smith 2017a).

In the blog proposing the DGC, Brad Smith—Microsoft’s president and chief legal officer—uses the metaphor of a new battle (battleground, plane of battle) four times and ‘nation-state attack’ fifteen times. The solution to this new battleground threat is found in an analogy:

‘Just as the Fourth Geneva Convention has long protected civilians in times of war, we now need a Digital Geneva Convention that will commit governments to protecting civilians from nation-state attacks in times of peace’. (Smith 2017a)

The analogy emphasises a new role for Microsoft:

‘And just as the Fourth Geneva Convention recognized that the protection of civilians required the active involvement of the Red Cross, protection against nation-state cyber attacks requires the active assistance of technology companies’. (Smith 2017a)

In protecting civilians from cyber attacks, Microsoft is presented as a neutral ‘first responder’ akin to the Red Cross. Other realities—such as the fact that Microsoft had recently won a $927 million contract to provide tech support to the US Department of Defense—are obscured in this analogy (Weinberger 2016).

Conflict in the cyber domain is also like kinetic conflicts in many ways, and I am not arguing that borrowing concepts or thinking in terms of conventional war will never be useful for regulating cyber conflict. Rather, by compiling these shortcomings I seek to highlight that this metaphorical framing should not be the only, or even the primary, framework for negotiating international cybersecurity. Metaphors based on the health of systems offer, for example, an alternative to the one of war.

5.2 Public Health

The CyberGreen Institute—a non-profit stemming from the Asia Pacific Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) community—works to improve cybersecurity through monitoring what they describe as the ‘health of the global cyber ecosystem’ (CyberGreen 2014). CyberGreen argues that ‘traditional approaches to cybersecurity from a national security or law enforcement perspective’ are limited because they rely on the decision-making of nation states rather than the ‘variety of key stakeholders comprising the cyber ecosystem’. These approaches also take a reactive posture to threats and often overlook proactive measures to improve underlying conditions:

‘Such approaches are analogous to treating a case of malaria through medicine, while leaving the nearby mosquito swamp untouched or developing cancer treatment technology while paying little attention to the population’s tobacco use’ (CyberGreen 2014)

In contrast, CyberGreen takes direct inspiration from the ‘public health model’ for cybersecurity, and particularly organisations such as the World Health Organisation (WHO). This is a clear example of a generative metaphor, which is often alluded to in CyberGreen’s website, blog, and training materials (see Fig. 1).

Screenshot from ‘Improving Global Cyber Health’ infographic (CyberGreen 2016b)

The metaphor is not limited to a general approach, as the public health model generates specific policies such as producing global statistics on health risk factors akin to the WHO’s Indicator and Measurement Registry (IMR). CyberGreen treats the IMR as a blueprint for statistical methods and data collection techniques to ensure harmonised ‘cross-comparable’ statistics which can be used by national CERTs (CyberGreen 2014). Like public health officials tracking obesity, CyberGreen runs its own proprietary Internet scans to detect the use of services such as Open recursive DNS or Open NTP, which can be vulnerable to amplifying distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks.Footnote 4 Due to the massive traffic volume that can be produced by large-scale DNS amplification-based DDoS attacks, there is often little that the victim can do to counter such an attack once it has started. Although these attacks—and other DDoS attacks more broadly—can be mitigated, it is often expensive or complex, particularly for smaller organisations. However, at the level of server operators like Google or national governments that regulate servers, it is possible to reduce the number of servers or botnets that can be used to increase traffic volume (US-CERT 2016). CyberGreen publishes metrics about insecure servers and compiles them into persuasive visualisations (see Fig. 2).

These metrics help CyberGreen to convince and motivate national stakeholders to ‘clean up their own cyber environments’ without ‘naming and shaming’(CyberGreen 2014). Recent studies show that metrics collected by third parties, such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, are a powerful and increasingly common governance mechanism (Cooley and Snyder 2015). Such mechanisms regulate state behaviour indirectly, through the social pressure created by quantification and rankings.

Health metaphors can also be encoded into computational simulations. For example, a research paper from the US Army Laboratory argues that:

‘just as simulations in healthcare predict how an epidemic can spread and the ways in which it can be contained, such simulations may be used in the field of cybersecurity as a means of progress in the study of cyber-epidemiology’. (Veksler et al. 2018, p. 2).

Network modelling techniques developed for biological viruses have subsequently been adapted to map the spread of computer viruses (Cheng et al. 2011; Hu et al. 2009).

A similar set of norms—which are not explicitly endorsed by CyberGreen—encourage companies and individual users to practice good cybersecurity or ‘cyber hygiene’. This language has been particularly prominent in the UK National Cyber Security Centre’s (NCSC 2017) ‘Cyber Essentials’ scheme. For example, good cyber hygiene might involve patching software and changing passwords frequently. Although such practices are widely recommended by the cybersecurity community, the metaphor of hygiene may shift partial responsibility onto the user, implying they may be blamed for a cyber attack if they did not take the recommended cybersecurity measures. Negative obligations are noticeably absent within the conceptual framework of public health.

This is an interesting example of how metaphors shape ethical reasoning; as biological viruses do not have moral agency, they cannot be held responsible for their actions. Therefore, the public health model removes focus from banning bad behaviour.

5.3 Ecosystem

Cybersecurity practitioners use the phrase ‘cyber ecosystem’ frequently. For example, it appears 15 times in the new US Cybersecurity Strategy (DHS 2018). The metaphor of cyberspace as an ecosystem is particularly useful when considering the extent to which cyberspace has become a constitutive part of the reality in which we live. As Chehadé (2018) quips: ‘cyberspace as a distinct space is dead—all space is now cyber’. Floridi (2014) argues ICTs are creating ‘a new informational environment in which future generations will live most of their time’ and calls for an ‘e-environmental ethics’. The ecosystem metaphor reflects the interdependence of various interacting organisms and their informational environment—‘inforgs’ in the ‘infosphere’ in Floridi’s terms (Floridi 2014). Ecological metaphors also reflect the way interconnected systems support multiple (positive and negative) feedback loops; concepts from ecology have been applied to explain developments in offensive cyber policies (Fairclough 2018).

Norm entrepreneurs who took the metaphor of a cyber ecosystem seriously might aim for a Cyber Paris AgreementFootnote 5 rather than a Digital Geneva Convention. The 2016 Paris Agreement aims, in the long term, to hold global temperatures ‘well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels’ (Falkner 2016). Under the Paris Agreement states submit voluntary pledges called ‘nationally determined contributions’ (NDCs). State progress towards NDCs will be reviewed regularly against an international system for monitoring emissions and financial contributions (Peters et al. 2017). Unlike previous climate change agreements, which attempted to impose targets for states, the Paris Agreement relies on mobilising ‘bottom-up’ civil society and domestic pressure to stimulate more ambitious pledges and mitigation efforts (Falkner 2016).

Cybersecurity negotiators following an ecosystem model would start with the notion of a shared responsibility for a global ecosystem. Rather than defining an ‘armed attack’ or a taboo victim, negotiators would attempt to define the conditions necessary for a healthy ecosystem, akin to the 2 °C limit. They would then identify specific, measurable actions—for example, botnet reduction—which states can undertake to improve the cyber ecosystem. States could voluntarily set NDCs, and an international body and civil society could use data collection efforts such as CyberGreen’s metrics to verify compliance with NDCs. The notion of a ‘healthy ecosystem’ here indicates a concept of environmental health rather than public health. Although the metaphors of ‘cyber health’ and cyber ecosystem have a lot in common (such as a systemic approach to responsibility), they draw from different realms and carry slightly different implications for responsibility. Most importantly, while diseases such as malaria do not have human agency, problems like pollution are a direct result of human decisions.

A possible objection may point out that the notion of a healthy ecosystem implies a level of consensus that does not exist among states engaging in cyber conflict. Environmental pollution is generally a by-product of achieving other goals, such as prosperity. In environmental negotiations, states seek to limit these by-products because they recognise all states benefit from a healthy global ecosystem. Furthermore, state’s competing visions for the future of the Internet might make it challenging to define a healthy ecosystem: for example, some countries would prefer more government control, while others would see openness as a sign of health.

With these objections in mind, there are two important reasons why working within the environmental framework might be more constructive. First, discussions on defining a healthy cyberspace would help negotiators identify both high consensus areas, such as structural risk mitigation measures which would benefit all states, and which states agree on these issues. In contrast, international collaboration on structural risk mitigation simply was not prioritised in international initiatives following the war model. Focusing on structural risk mitigation may be useful as international collaboration to reduce botnets or take other actions that would make attacks less effective might help build trust before addressing more controversial issues.

Second, although climate change is now more widely accepted, environmental policy has decades of experience in addressing robust disagreement. Therefore, it provides mechanisms such as NDCs that prioritise flexibility: sceptical states can set low targets, while states that are more ambitious are rewarded for setting higher targets by comparison. This mechanism could be applied to a highly controversial aspect of cyber conflict: vulnerabilities disclosure.

Buchanan (2017) argues that one of the most effective actions states could take to mitigate mistrust and cyber conflict would be unilaterally disclosing zero-day vulnerabilities—i.e. vulnerabilities which have not yet been disclosed to the public or to software vendors. Nye (2015) similarly argues for the USA adopting a strategy of unilateral responsible disclosure. Like global warming, vulnerabilities are a threat to collective security. The counterargument to disclosure holds that governments which disclose zero-day vulnerabilities will lose valuable intelligence-collecting and strategic capabilities (Buchanan 2017). Yet, if a state wants to keep a vulnerability secret, it must accept that other threat actors may discover the vulnerability and target the state’s own citizens (as what happened in WannaCry). A state that discloses vulnerabilities may lose the ability to infiltrate certain systems, but it ensures that both domestic and global users are more secure from threat actors exploiting the vulnerability. Unilaterally disclosing vulnerabilities therefore also signals a state’s desire for stability.

This led Microsoft’s Brad Smith to call for vulnerabilities to be treated ‘like weapons in the physical world’ (Smith 2017b). However, as Buchanan (2017) points out, an arms control approach in which states promise not to stockpile vulnerabilities is hard to verify without intruding into a state’s networks. Positive acts (such as instances of disclosure) are easier to verify than the absence of negative acts (such as keeping vulnerabilities secret) because they are public and can be confirmed by the software vendor.

Existing processes for state disclosure of vulnerabilities, such as the US Vulnerability Equities Process, have been criticised for the low incentives states have to disclose vulnerabilities to the public (Ambastha 2019). Rather than relying solely on individual state’s desire for stability (which might easily be outweighed by their interests in intelligence gains), a Cyber Paris Agreement could create pressure for states to commit to measurable goals for responsibly disclosing more vulnerabilities. Due to the market for purchasing vulnerabilities, several mechanisms such as the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) exist for assessing the value of vulnerabilities (Ablon et al. 2014; Romanosky 2019). These scoring systems could be translated into a metric for state commitments. The mechanism of measurable commitments would enable flexibility (some states may not commit to any disclosures) while creating greater incentives for action.Footnote 6 In the words of Yurie Ito, CyberGreen’s founder, ‘what gets measured, gets done’ (CyberGreen 2016a).

The metaphor sceptic might object that policy-makers could adapt environmental policy mechanisms to cybersecurity without seeing cyberspace as an ecosystem. However, the notion of a shared ecosystem elicits the concept of shared responsibility. Environmental activists have been highly successful in convincing international audiences of the existence of a shared threat (Gough and Shackley 2001). Drawing on an environmental metaphor allows us to take advantage of the generative effect of the metaphor and transfer existing understandings about roles and responsibilities towards the global ecosystem to a new domain.

The ecosystem metaphor also allows for a far more holistic ethical approach than one of war, which reduces the complex dynamics of cyber conflict to a focus purely on adversarial states and therefore takes away attention from the roles and responsibilities of relevant actors like CERTs or companies. Rather than thinking simply in terms of protecting one’s own systems, the cyber ecosystem suggests a relational responsibility for a shared ecosystem. National actors—both CERTs and governments—should address the risks computers in their networks pose to others.

Even if aspects of the proposed environmental model fail—for example, if no amount of regulatory innovation or civil society activism convinces states to commit to specific numbers of disclosures—simply imagining how negotiators might apply the ecosystem framework to cybersecurity ipso facto is useful, as it exposes the constitutive effect of cyber war. This metaphor leads us to focus narrowly on conflict (and deterring conflict) in the first place, rather than more broadly on proactive, holistic international cybersecurity policy. This cannot be addressed merely by avoiding words like cyber war, as omissions do not provide an alternative framework. However, applying another strong metaphor to the same issues shows that the war framework is an option rather than an obvious consequence of the way things are.

5.4 Infrastructure

Cybersecurity can also be considered with respect to the stability of the cyberspace as an infrastructure. For example, the first major norm proposed by the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace (GCSC) states that:

‘Without prejudice to their rights and obligations, state and non-state actors should not conduct or knowingly allow activity that intentionally and substantially damages the general availability or integrity of the public core of the Internet, and therefore the stability of cyberspace’ (GCSC 2017, added emphasis).

The GCSC is an international, multi-stakeholder effort launched in 2017. It has consciously moved away from the language of cyber war and security, which is particularly evident in the GCSC’s motto: ‘Promoting stability in cyberspace to build peace and prosperity’. The concept of the ‘public core’, first introduced by Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy in 2015, stipulates that the Internet’s main protocols and infrastructure are a global public good and must be safeguarded against unwarranted intervention by states (Broeders 2017). The GCSC defines the public core to include packet routing and forwarding, naming and numbering systems, the cryptographic mechanisms of security and identity, and physical transmission media. Attacks on any of the activities, one could deduce, would be considered attacks to the public core of the infrastructure and, therefore, should be forbidden.

As Broeders (2017) notes, earlier proposals for what should be included in the concept of the public core include literal physical infrastructures, such as DNS servers and sea cables. However, the logical layers of protocols and standards (as well as cryptography following the GCSC norm), although they are not physical, territorial structures, can still be imagined as the core of a massive infrastructure. Therefore, the ban on attacking the public core draws on an intuitive spatial metaphor: if we all lived in a building with a shared foundation (i.e. the Internet), it would be immoral to attack the foundations of this building for personal gain.

Although the ban on attacking the public core norm follows a similar logic to the taboos set by IHL on certain targets, by banning attacks on certain kinds of infrastructure, the GCSC cleverly avoids many of the pitfalls of distinguishing between civilian and military targets. Unlike the metaphors of health and ecosystem, the metaphors of online infrastructure avoids naturalising cyberspace as something pre-existing or ‘God-made’, and therefore may be better for emphasising ethical design rather than conservation.,

To illustrate how this might shift the burden of responsibility, consider the example of WannaCry outlined at the beginning of this paper. Following the Digital Geneva Convention’s war framing, Smith’s (2017b) response to WannaCry suggests that ‘[an] equivalent scenario with conventional weapons would be the U.S. military having some of its Tomahawk missiles stolen’. Governments should treat WannaCry as a wake-up call and ‘adhere in cyberspace to the same rules applied to weapons in the physical world’ (Smith 2017b). According to this proposal, governments should protect civilians and tech companies from foreign attacks and disclose vulnerabilities which might make civilian infrastructure vulnerable to attack.

In contrast, in regulating a global architecture, the designers of digital environments have a strong obligation to build infrastructure carefully and safely (without the vulnerabilities which made WannaCry possible), and governments may have an additional obligation to regulate companies within their territory to ensure that they do so. Returning to the building metaphor, if a government knows of a structural (yet fixable) flaw in a building in which many of its own citizens (as well as international citizens) live, it would be unethical to keep that knowledge secret. Microsoft itself also relies at times on architectural metaphors, as when it acknowledges that as ‘builders of the digital world’, tech companies have the first responsibility to respond to attacks on the Internet (Smith 2017b).

The regulation of large-scale infrastructure may therefore be a generative source for policy. Humans have never previously built infrastructures so vast that they were shared by citizens from all over the planet. As large infrastructure projects are usually regulated nationally, it is not clear how framing the problem of cybersecurity in terms of infrastructure provides a framework for international governance. However, generative metaphors do not need to carry over fully formulated laws or regulatory frameworks from one area to another. Like ‘the paintbrush is a pump!’ example in Schön’s (1979) paper, the metaphor of infrastructure could be a thinking tool which opens up space for creative, collaborative policy-making.

6 Conclusion

When designing international governance for cybersecurity, should we negotiate over a war, public health, an ecosystem, or a global architecture? Each metaphor identifies a different problem to be solved and expresses a different set of arguments about responsibility. Therefore, theorists and policy-makers should evaluate the metaphorical framing of negotiations and regulatory approaches. Metaphors do not just suggest a general approach, as many policy analysts suggest. On the contrary, they can prescribe specific policies: policy-makers in a cyber war must protect their population, avoid attacks on taboo targets, and punish and deter wrong doers. In contrast, policy-makers in a cyber ecosystem must commit to mitigating systemic risks that threaten this shared environment.

Table 1 summarises the obligations suggested by the four metaphorical frameworks outlined in this essay.Footnote 7 How do we compare and evaluate between these approaches? Should we look for how developed and well-accepted various normative regimes are? Or should we instead prioritise analytical clarity or how well the metaphor ‘fits’? Or should we perhaps think instead of mundane and inescapable political realities, and ask which metaphor is the most persuasive? Which one will be accepted by the powers that be?

A full answer to this question would require another paper and may not in fact be possible, as there is no objective way to trade-off benefits and limitations of different metaphors. Perhaps a good starting point would be to ask instead: what kind of responsibility do we want in this new domain? Do we want the obligations to protect civilians to fall solely on the state, or the creators of digital infrastructures, or on individual technology users? Should states be responsible only for their own security, or should they recognise a wider shared responsibility?

In this paper, I have argued that assuming uncritically a certain metaphor bypasses explicit consideration of these problems, by matching the new problem of cyber conflict to an existing problem with set roles and responsibilities. In particular, the metaphor of war introduces a reductionist notion of state responsibility, which obscures the possibility for cooperation on improving structural features of cyber conflict. The interdependence of digital infrastructures—as illustrated by the complexity of campaigns like WannaCry—renders a focus on securing one’s border against outsiders seem outdated.

Through exploring these metaphors, I also elaborate a method for policy-makers and researchers to critically assess policy metaphors: first, identify metaphors which structure the regulation of new technologies, particularly cases where this structure is problematic; second, seek out other metaphors which might be applied to the same policy area; third, by contrasting these competing metaphors, generate a wider variety of potentially useful policies and regulatory approaches.

Problems posed by new technologies require both imagination and analytic rigour. No single metaphor will fully capture the nuances of cybersecurity governance. Different metaphors can be part of a conceptual toolkit in which policy-makers are reminded of each metaphors’ implicit associations and deficiencies as well as its useful contributions. Analysing policy at the level of metaphor allows both for more creative solutions and a more systematic analysis of the role of imagination in policy. It also serves as a useful reminder that war in new domains is not the inevitable result of geopolitics or technological development. We can and should construct a more collaborative system for international cyber-politics (Lukes 2010).

Notes

In fact, since the first draft of this paper, two fora for such discussions (United Nations Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation and the General Assembly Open-Ended Working Group) have been formed, making this statement more of a policy proposal than a thought experiment.

It is useful to note that the concept of war emerged later than we might think; ancient Romans spoke of ‘conquest’ rather than war (van der Dennen 1995).

This approach is inspired by Lukes’ (2010) guide to ‘metaphor hacking’.

In amplification attacks, attackers try to exhaust a victim’s bandwidth by abusing the fact that protocols such as DNS or NTP allow spoofing of sender IP addresses (see US-CERT 2016).

This is a hypothetical proposal, not to be confused with the recent ‘Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace’ a proposal brought forward by the French government in November 2018.

Of course, states might choose to only give up vulnerabilities in cases where they have a second vulnerability which guarantees their ability to exploit the same systems. However, even such seemingly useless disclosures will make most users safer, as third parties will be less able to exploit these vulnerabilities when they are disclosed.

This is an indicative list of proposed obligations for states within each conceptual framework—obligations for private actors are italicized. The norm initiatives do not necessarily advocate all of the norms in their category.

References

Ablon, L., Libicki, M. C., & Golay, A. A. (2014). Markets for cybercrime tools and stolen data: Hackers’ bazaar. Rand. https://doi.org/10.7249/j.ctt6wq7z6.

Ambastha, M. (2019). Taking a hard look at the vulnerabilities equities process and its national security implications. Berkeley Tech Law Journal. http://btlj.org/2019/04/taking-a-hard-look-at-the-vulnerableequities-process-in-national-security/.

Berr, J. (2017). ‘WannaCry’ Ransomware attack losses could reach $4 billion. CBS News.

Betz, D. J., & Stevens, T. (2013). Analogical reasoning and cyber security. Security Dialogue, 44(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010613478323.

Broeders, D. (2017). Aligning the international protection of ‘the public core of the Internet’ with state sovereignty and national security. Journal of Cyber Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/23738871.2017.1403640.

Brown, G., & Metcalf, A. O. (1998). Easier Said than Done: Legal Reviews of Cyber Weapons. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2643688.

Buchanan, B. (2017). The cybersecurity dilemma: Hacking, trust and fear between nations. Oxford Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof.

Chehadé, F.. (2018). Joseph Nye and Fadi Chehadé—norms to promote stability and avoid conflict in cyberspace | Blavatnik School of Government. Blavatnik School of Government. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/multimedia/video/joseph-nye-and-fadi-chehade-norms-promote-stability-and-avoid-conflictcyberspace. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Cheng, S. M., Ao, W. C., Chen, P. Y., & Chen, K. C. (2011). On modeling malware propagation in generalized social networks. IEEE Communications Letters. https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2010.01.100830.

Collier, J. (2018). Cyber security assemblages: A framework for understanding the dynamic and contested nature of Security provision. Politics and Governance, 6(2), 13–21 https://www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance/article/view/1324/1324. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Cooley, A., Snyder, J. (2015). Ranking the world: Grading states as a tool of global governance. Ranking the world: Grading states as a tool of global governance. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316161555.

CyberGreen. (2014). The Cyber Green Initiative: Concept paper improving health through measurement and mitigation.

CyberGreen. (2016a). Cyber security agency of singapore becomes cornerstone sponsor for CyberGreen. https://www.cybergreen.net/2016/10/11/Cyber-Security-Agency-of-Singapore-Becomes-Cornerstone-Sponsor-for-CyberGreen/. Accessed 10 May 2018.

CyberGreen. (2016b). Improving global cyber health. https://www.cybergreen.net/img/medialibrary/CGinfographic-2016-web.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Dev, P.. (2015). ‘Use of force’ and ‘armed attack’ thresholds in cyber conflict: The looming definitional gaps and the growing need for formal U.N. response. Texas International Law Journal.

DHS. (2018). U.S. department of homeland security cybersecurity strategy. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/DHS-Cybersecurity-Strategy_1.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Eco, U., & Paci, C. (1983). The scandal of metaphor: Metaphorology and semiotics. Poetics Today, 4(21) https://www.jstor.org/stable/1772287?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Fairclough, G. (2018). Offensive cyber, ecology and the competition for security in cyberspace: The UK’s approach. http://podcasts.ox.ac.uk/offensive-cyber-ecology-and-competition-security-cyberspace-uksapproach.

Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. International Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12708.

Floridi, L. (2014). The 4th revolution: How the Infosphere is reshaping human reality (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-fourth-revolution-9780199606726?cc=gb&lang=en&. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Froomkin, A. M, et al. (1995). “Anonymity and Its Enmities.” J. Online L. Art.

GCSC. (2017). Call to protect the public CORE of the Internet. New Delhi. https://cyberstability.org/news/global-commission-proposes-definition-of-the-public-core-of-the-internet/. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Giles, K., Hagestad, W. II. (2013). Divided by a common language: Cyber definitions in Chinese, Russian and English. 5th International Conference on Cyber Conflict, 1–17.

Gill, L. (2017). Law, metaphor and the encrypted machine. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 13(16) https://ssrn.com/abstract=3138684.

Gough, C., & Shackley, S. (2001). The respectable politics of climate change: The epistemic communities and NGOs. International Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00195.

Grigsby, A. (2017). The end of cyber norms. Survival, 59(6), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2017.1399730.

Hu, H., Myers, S., Colizza, V., & Vespignani, A. (2009). WiFi networks and malware epidemiology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0811973106.

Johnson, M. (1993). Moral imagination: Implications of cognitive science for ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jones, M. L. (2017). The spy who pawned me. Limn, no. 8. https://limn.it/issues/hacks-leaks-and-breaches/. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Kello, L. (2017). The Virtual Weapon and International Order. Yale University Press.

Korzak, E. (2017). UN GGE on cybersecurity: The end of an era? The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2017/07/un-gge-on-cybersecurity-have-china-and-russia-just-made-cyberspace-less-safe/. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G. (1991). Metaphor and war: The metaphor system used to justify war in the Gulf. Peace Research, 23(2), 25 https://sfx.unimelb.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/sfxlcl41?sid=google&auinit=G&aulast=Lakoff&atitle=Metaphor and war:The metaphor system used to justify war in the Gulf&title=Peaceresearch&date=1991&spage=25&issn=0008-4697.

Lapointe, A. (2011). When good metaphors go bad: The metaphoric ‘branding’ of cyberspace. Center for Strategic & International Studies. http://csis.org/publication/when-good-metaphors-go-bad-metaphoricbranding-cyberspace. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Lotrionte, C. (2017). Geopolitics eclipses international law at the UN. The Cipher Brief, August 6, 2017. https://www.thecipherbrief.com/geopolitics-eclipses-international-law-un-1092. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Lukes, D. (2010). Hacking a metaphor in five steps. Metaphor Hacker. http://metaphorhacker.net/2010/07/hacking-a-metaphor-in-five-steps/. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Maurer, T. (2011). Cyber norm emergence at the United Nations. International Relations, September, pp 1–69. http://belfercenter.hks.harvard.edu/files/maurer-cyber-norm-dp-2011-11-final.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2018.

McKune, S. (2015). An analysis of the International Code of Conduct for Information Security. https://citizenlab.ca/2015/09/international-code-of-conduct/. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Nye, J. (2017). A normative approach to preventing cyberwarfare. Project Syndicate. https://www.projectsyndicate.org/commentary/global-norms-to-prevent-cyberwarfare-by-joseph-s%2D%2Dnye-2017-03?barrier=accesspaylog. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Nye, J. S. (2015). The world needs new norms on Cyberwarfare. The Washington Post, 2015.

Peters, G. P., Andrew, R. M., Canadell, J. G., Fuss, S., Jackson, R. B., Korsbakken, J. I., Le Quéré, C., & Nakicenovic, N. (2017). Key indicators to track current progress and future ambition of the Paris Agreement. Nature Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3202.

Rid, T. (2012). Cyber war will not take place. Journal of Strategic Studies, 35(1), 5–32.

Rodríguez, M. (2017). Declaration by Miguel Rodríguez, representative of Cuba, at the final session of group of governmental experts on developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security.

Romanosky, S. (2019). Developing an objective, repeatable scoring system for a vulnerability equities process. Lawfare. https://www.lawfareblog.com/developing-objective-repeatable-scoring-system-vulnerabilityequities-process. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Sauter, M. (2017). “The Illicit Aura of Information.” Limn, no. 8

Schmitt, M. N., Vihul, L. (2014). The nature of international law cyber norms. The Tallinn Papers, No. 5, pp 1–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952804.

Schön, D. A. (1979). Generative metaphor: A perspective on problem-setting in social policy. Metaphor and Thought. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139173865.

SCO. (2009). Annex 1 to the Agreement Between the Governments of the Member States of the SCO in the Field of International Information Security.

Shimko, K. L. (1994). Metaphors and foreign policy decision making. Political Psychology, 15(4), 655. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791625.

Smith, B. (2017b). The need for urgent collective action to keep people safe online: Lessons from last week’s cyberattack. Microsoft on the issues. https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2017/05/14/need-urgentcollective-action-keep-people-safe-online-lessons-last-weeks-cyberattack/#sm.000bi5yyf12twdrz104kfp70qrzfk. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Smith, B. (2017a). The need for a digital Geneva convention. Microsoft on the issues. https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2017/02/14/need-digital-geneva-convention/. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Taddeo, M. (2016). On the risks of relying on analogies to understand cyber conflicts. Minds and Machines. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-016-9408-z.

Taddeo, M. (2017). The limits of deterrence theory in cyberspace. Philosophy & Technology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-017-0290-2.

Taddeo, M., & Luciano, F. (2018). Regulate Artificial Intelligence to Avert Cyber Arms Race Comment. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-04602-6.

Thibodeau, P. H., & Boroditsky, L. (2011). Metaphors we think with: The role of metaphor in reasoning. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016782.

UK National Cyber Security Centre. (2017). Cyber security small business guide. Cyber Essentials.

UNGA. (2015). Report of the secretary general: Developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security.

UNGA. (2016). Report of the secretary-general developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international Security.

UNGA. (2017). Report of the secretary-general developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security.

US-CERT. (2016). DNS amplification attacks | US-CERT. US-CERT. 2016. https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/alerts/TA13-088A.

van der Dennen, J.M.G. (1995). The origin of war. University of Groningen.

Vee, A. (2012). Text, speech, machine: Metaphors for computer code in the law. Computational Culture.

Veksler, V. D., Buchler, N., Hoffman, B. E., Cassenti, D. N., Sample, C., & Sugrim, S. (2018). Simulations in cyber-security: A review of cognitive modeling of network attackers, defenders, and users. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00691.

Weinberger, M. (2016). Microsoft wins $927 million contract with Department of Defense—business insider. Business Insider. http://uk.businessinsider.com/microsoft-wins-million-defense-contract-2016-12?r=US&IR=T.

Wolff, J. (2014). Cybersecurity as metaphor: Policy and defense implications of computer security metaphors. TPRC Conference Paper, 1–16. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Cybersecurity+as+Metaphor:+Policy+and+Defense+Implications+of+Computer+Security+Metaphors+Josephine#0. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Mariarosaria Taddeo, whose advice and feedback was invaluable to the completion of this project and who co-authoured an earlier version of this paper in the Yearbook of the Digital Ethics Lab 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Slupska, J. War, Health and Ecosystem: Generative Metaphors in Cybersecurity Governance. Philos. Technol. 34, 463–482 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00397-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00397-5