Abstract

This article discusses some essential differences between the Cartesian and neo-Aristotelian conceptions of child development. It argues that we should prefer the neo-Aristotelian conception since it is capable of resolving the problems the Cartesian conception is confronted by. This is illustrated by discussing the neo-Aristotelian alternative to the Cartesian explanation of the development of volitional powers (the ideo-motor theory), and the neo-Aristotelian alternative to the Cartesian simulation theory and theory–theory account of the development of social cognition. The neo-Aristotelian conception is further elaborated by discussing how it differs from both behaviorism and cognitive neuroscience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Descartes distinguished the mental realm from the physical realm. He argued that only humans have a mind, that the mind is a separate immaterial substance (its essence is thinking), and that the mind is causally connected to (the pineal gland of) the brain. By distinguishing the mind from the body and brain, Descartes, in opposition to the Aristotelian tradition, sharply divided the study of nature from the study of human thought and consciousness.

Aristotle, the biologist of the mind, conceived of the psuchē (often translated as "soul," but since this term may be misleading, I use the term "psuchē") as the set of potentialities the exercise of which is characteristic of the organism. What is distinctive about the human psuchē is that it incorporates not only the vegetative powers of growth, nutrition, and reproduction, and the sensitive powers of perception, desire, and motion, but also the rational capacities of intellect and will. The psuchē is not, in contrast to what Descartes believed, an entity causally connected to the body, but is characterized as the "form" of the living body. Mental predicates such as "consciousness" or "emotion" are attributed to the organism as a whole (or the human being; De anima, 408b12–408b15). They are not attributes of the (immaterial) res cogitans, let alone of the brain.

Neo-Aristotelians add that the exercise of powers of an organism is visible in its behavior, for example, in behavioral manifestations of emotions and linguistic expressions of thoughts (see Kenny 1989, Chaps. 1–3; Hacker 2007, Chaps. 8–10; and Smit 2014, Chaps. 2, 4, 5). They argue that there is a logical or conceptual connection between "the internal, mental realm" and "the external, corporeal realm." By contrast: the mental characteristics mentioned by Descartes are logically unrelated to what individuals do, because the res cogitans is in Descartes’ conception unrelated to behavior. The Cartesian mind (the thinking substance) does not behave: minds think and are conscious (they feel, judge, will, perceive, and so forth) but these are not forms of (corporeal) behavior. They can cause the behavior of their bodies, for there is, according to Descartes, an external, causal interaction between mind and body. But the resulting bodily movements we see are not what neo-Aristotelians call behaviors (expressions or manifestations of their emotions or thoughts), but "mechanical movements," i.e., movements of a biological machine, because humans are, according to Descartes, conscious minds causally united to machines. The other animals are mere automata lacking a mind (the vegetative and sensitive psuchē were held by Descartes to be explicable in mechanical terms).

In this article I discuss how these two opposing views return in explanations of the development of the mind. Since minds can, according to Descartes, cause the behavior of their bodies, the Cartesian conception raises the question of how we can understand the development of mental acts or states causing behavioral changes in children. I shall discuss in the third, fourth, and fifth sections the Cartesian ideo-motor theory as an answer to this question and its neo-Aristotelian alternative. The complementary question is how children acquire an understanding of another mind if they can only observe movements of a biological machine. The Cartesian answer to this question is that children acquire an understanding by constructing a theory of mind. In the sixth section I discuss and criticize the concept of a theory of mind. The neo-Aristotelian conception of the development of (social) cognition and how it differs from behaviorism and cognitive neuroscience is discussed in the last two sections before the conclusion.

The Cartesian Conception: Some Characteristics

As an introduction to how differences between the Cartesian and neo-Aristotelian conceptions return in developmental science, I will start by briefly discussing some Cartesian ideas of Tomasello (1999).

According to Descartes humans have privileged access to the internal, mental realm (it does not belong to the public domain). How they know that others have pain, for example, or pursue a goal, is less clear, for they do not have access to the mental experiences of others (they cannot peer into another mind). Tomasello (1999, p. 70) makes a similar distinction and argues that it is a "key theoretical point" that "we have sources of information about the self and its working that are not available for any external entity of any type." For example, if we perform an act, we have available the internal experience of a goal and of striving for a goal, as well as the various forms of proprioception of our behavior if we act to attain the goal. Tomasello presupposes that, during the early stages of development, children learn voluntary, goal-directed movements through proprioception and experience and by attending to their experiences. Yet he does not pay further attention to how inner experiences are involved in the development of volitional, goal-directed behavior: they are treated by him as given. Tomasello’s investigations focus on the question of how children learn to understand mental acts, processes, states, and events of others. His proposed solution is (a variant of) the so-called simulation hypothesis: according to Tomasello, children gain an understanding of the mental acts, states, and so on of others by adopting the "like me"-stance (or the analogy to the self). For instance, because 9- to 12-month-old children (begin to) understand their own wants, goals, and intentions, they can simulate another person’s psychological functioning by analogy to their own, "which is most directly and intimately known to them" (Tomasello 1999, p. 71).

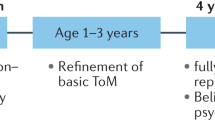

Tomasello distinguishes stages in the development of social behavior. He argues that there is a gradual distancing of the mental component from concrete action. Tomasello (1999, p. 179) distinguishes three levels: animacy, intentionality, and mentality. Animacy is only expressed in behavior; intentionality is also expressed in behavior but may be "somewhat divorced" from behavior since it may be unexpressed or expressed in different ways (there are different ways to pursue a goal); and mentality, concerning desires, plans, and beliefs, has no necessary behavioral reality at all. Tomasello suggests that the development of social cognition proceeds from understanding animacy during infancy (from early on, infants can discriminate between the animate and inanimate), to understanding intentional agents (1 year), to understanding mental agents (about 4 years). He emphasizes that understanding others as mental agents is difficult for children, for in contrast to animacy and intentionality, thoughts and beliefs lack any natural expression in behavior and are invisible (I shall discuss below why, although there are no natural, behavioral precursors of beliefs and thoughts, beliefs and thoughts are expressed in linguistic behavior. It is a moot question whether we call linguistic behavioral expressions natural or not). And because it is more difficult to understand the invisible mental states of others, it takes time to develop, clarifying why children begin to understand that others are mental agents when they are about 4 years old. Tomasello argues that, by engaging in interactions and discourses (after they have learnt the use of gestures like pointing and later language), children gradually acquire the understanding that others have thoughts and beliefs different from their own.

The Cartesian Account of the Development of the Will

Tomasello presupposes that children acquire volitional powers as the result of maturation of the brain, proprioception, and experiences. However, like many other researchers, he does not say much about how children acquire these powers. Candlish (1995) has argued that the current ideas of cognitive psychologists and cognitive neuroscientists on volitional behavior can be traced back to ideas proposed by William James and others in the 19th century.

The background for discussions of the will by psychologists is Hobbes’ refinement and extension of Descartes’ ideas (see Hacker 1996, Chap. 7). Hobbes added to Descartes’ ideas the concept that the imagination is the first internal beginning of all volitional motion, because voluntary movements are dependent upon an antecedent thought, i.e., a thought about what movement someone wants to perform, in which direction he or she wants to move, and in which way he or she wants to execute the movement. Thoughts, according to Hobbes, give rise to endeavors (later conceived as trying or making an effort): these are the beginnings of motion in the human body and are antecedent to actions such as walking or raising a hand. Hence, endeavors seem to explain how volitional movements are initiated by and proceed directly from the mind. However, Hobbes’ suggestion raises a problem, since a role for the imagination in the initiation of voluntary movements presupposes the availability in the imagination of thoughts or images of such movements. It was assumed that children acquired ideas or memory images of movements during the early stages of development. For example, Wernicke (1874) explained the voluntary movements involved in speech as the result of memory images in the cortex that children acquire from kinesthetic sensations coming from laryngeal movements and movements of the tongue, lips, and so on. James explained the origin of volitional behaviors in a similar way: since babies display instinctual behaviors (like suckling), have reflexes, and exhibit non-volitional movements, these involuntary movements leave a kinesthetic (or what nowadays is called "proprioceptive") image in the memory, and "then the movement can be desired again, proposed as an end, and deliberately willed" (James 1950[1890], vol. 2, p. 487). And like Wernicke, James argued that the acquired ideas or images are later involved in the production of voluntary movements. "For a million different voluntary movements, we should then need a million distinct processes in the brain-cortex (each corresponding to the idea or memory-image of one movement), and a million distinct paths of discharge" (James 1950[1890], vol. 2, pp. 497–498). Given the amount of neurons in the cortex and the connections between them, James believed that there is a sufficient number of areas in which the countless images can be stored.

When children have acquired a supply of ideas and know that it is within their power to obtain what they desire, according to James they have acquired the ability to act voluntarily. On the one hand this is linked to learning what appropriate objects of the will are; on the other hand it is learning how to obtain them as the result of bodily movements produced by a mental act or event that constitutes willing. How do these images, mysteriously stored in the brain, result in voluntary, goal-directed movements? It was assumed that there must be guiding afferent kinesthetic sensations for the successful carrying out of a concatenation of movements, otherwise the will could not know what it brings about. As James put it: we need to know for each movement just where we are in it, otherwise we are sure to get lost soon and go astray (James 1950[1890], vol. 2, p. 491). Yet Wundt, Bain, Mach, Helmholtz, and others argued that mere images of movements stored in our memory are not sufficient for performing volitional, goal-directed behavior. According to them, there must also be feelings of innervation, i.e., efferent sensations of volitional energy going out of the brain and linked to the nerves activating the muscles involved in the appropriate movements. These feelings are necessary, for otherwise we could not tell whether a particular electric current was the right one to innervate the appropriate muscles. James criticized the ideas of Wundt and others: there is, according to him, no empirical evidence of the presence of these feelings of innervation. James suggested that thoughts are themselves impulsive. There need be nothing more in the mind antecedent to the execution of a voluntary movement than the bare idea of the movement’s sensory, kinesthetic effects. The movement follows unhesitatingly the anticipatory image of it in the mind. "We think of the act, and it is done; and that is all introspection tells us of the matter" (James 1950[1890], vol. 2, p. 522). Hence, we do not add something dynamic to get a movement. However, in exceptional cases there are instances of inhibition by an antagonistic thought in our mind, which manifest conflicting desire. Other ideas (of prospective movements) inhibit then the impulsive power of a given motor image. When the blocking is released, "we feel as if an inward spring were let loose, and this is the additional impulse or fiat upon which the act effectively succeeds" (James 1950[1890], vol. 2, p. 527). Thus in these cases the act results from some "super-added will-force."

The Ideo-Motor Theory is Mistaken

There are several reasons why the ideas of Wundt, James, and others are mistaken (see Hacker 1996, Chap. 7; Bennett and Hacker 2003, Chap. 8; Nachev and Hacker 2014). I discuss three of them.

First, their conception distorts the distinction between action and reaction, and between voluntary and involuntary acts. There is a difference between something happening in my mind causing a movement and moving because I want to do or obtain something. When there occurs a mental image in my mind of a movement (or a thought of a movement, or a felt desire) and this image causes a bodily movement, then it is an example of a reaction (not of a voluntary action). A thought of something fearful may cause me to tremble, a comic image may cause me to smile, and the occurrence of erotic desire may have bodily reactions as well. But these are not things we do at will. Of course, because we know of these bodily reactions, we may bring them about at will by thinking appropriate thoughts. But this only shows that we can engage voluntarily in thinking and imagining and that we can bring about bodily reactions at will by trying. The point to notice is that bringing about bodily reactions by thinking and imagining are not paradigmatic examples of voluntary actions.

Secondly, their ideas about the "willing self" distort the concept of agency. We are the agents of our voluntary actions, not an alleged willing self in our skull (see further Bennett and Hacker 2003; Smit and Hacker 2014). Voluntary acts are acts that we decide and intend to perform, can perform on request, can learn to perform, can be done with care, and are acts we are responsible for. If our actions are merely bodily movements caused by desires, wishes, or impressions that occur to us, as Wundt, James, and others thought, then the agent drops out of the account. It is therefore more interesting to elucidate the differences between those actions of which we are the agent and those actions that are caused by mental events that occur in our minds, such as blushing with embarrassment or trembling with agitation (and other responses to thoughts and feelings we have). In these cases the cause of our "movements" is "within us." But our "movements" are then not voluntary: we do not say that voluntary actions were caused by our desires, but rather that we did them of our own volition, clarifying why we are responsible for our voluntary acts.

Thirdly, Wundt and James postulated that the motor images (the antecedents of voluntary behavior) originate in part in afferent kinesthetic sensations. They assumed that these sensations provide us with information. It is important to see why Wundt, James, and others were confused about the role of kinaesthetic sensations. This can be explained by discussing the (conceptual or logical) differences between seeing or perceiving something, feeling a sensation like a pain, and a kinesthetic sensation. When we see the color of a flower, we see that it is such-and-such a color, and when we smell what is cooking in the kitchen, we smell that such-and-such food is cooking. But if we feel a sensation (a pain), we do not perceive anything (having and feeling a sensation are logically not connected to that-nominalizations and Wh-clauses). When we feel a pain, we have a sensation. Kinesthetic sensations seem to be different from a sensation like a pain, for they seem to provide us with information. One can argue that they are for this reason more akin to a perception. Yet we do not have the information provided by kinesthetic sensations as the result of a perception (just as we do not perceive pain by an inner sense, for there are no inner sense organs with which we perceive sensations). How, then, should we characterize the information provided by these sensations? James argued that kinesthetic sensations provide us with information because they are always present (though they are most of the time subliminal), explaining why individuals are always able to judge the position and motion of their limbs. He had two arguments. First, malfunctioning of afferent nerves, and a local anesthetic leading to the absence of these sensations, deprive an individual of his or her ability to judge correctly where his or her limbs are or whether they are moved. Secondly, although under normal conditions we do not notice the sensations, we can intensify the sensation (for instance during an experiment), or, if we attend to our movements, can bring them to consciousness and feel them (notice that the alternative explanation, that they are created by attending to the movement, leads to absurdities). However, James’ arguments are misguided, for we do not have criteria to differentiate between a kinesthetic sensation of which we are unaware and no kinesthetic sensation. James’ insistence that we constantly have kinesthetic sensations providing us with information is not to state a remarkable fact, but to opt for a Cartesian form of description (i.e., a response to the demands of the Cartesian conception that there must be sensations providing us with information). The problem is that our knowledge of, for example, our hands raised is in normal circumstances not derived from the sensations (for there is no such thing as identifying them with an inner sense). Hence the kinesthetic sensations are not a source of knowledge (by contrast: perceiving a flower in the garden is a source of knowledge), but merely a condition of its possibility (see further Malcolm 1984; Hacker 1996, Chap. 7). Kinesthetic sensations, we can conclude, are a prerequisite for our ability to know how our limbs are disposed and move. The underived awareness of the disposition of our limbs is essential for the ability to engage in voluntary and purposive movements.

The neo-Aristotelian criticism leads to the conclusion that the Cartesian presupposition that volitional behavior is either caused by a mental act or event is for conceptual reasons misguided. Willing is not caused by an act of the mind, for if willing were voluntary, then it would have been caused by an antecedent volitional act, raising the question whether this act is caused by an antecedent volition, and so on (it leads to a regress). And the alternative that willing is an event is also not an explanation: if willing were an event that happens when it happens, then the behavior performed would not be voluntarily performed at all.

The Neo-Aristotelian Conception of Voluntary Behavior

If the conclusion that the Cartesian conception of voluntary acts is incoherent is correct, then we can ask how the alternative neo-Aristotelian conception characterizes the development of volitional behavior. Neo-Aristotelians emphasize that, if there are "acts of will" or "willpower" involved, they should not be conceived as acts of a Cartesian "I" self, or ego, but in terms of the actions or acts of the agent: his or her determination, persistence, and tenacity in pursuit of goals.

Basic human goal-directed actions, such as eating, drinking, walking, speaking, and so on, are volitional. These volitional powers develop during the first year. Reflexes and instinctual behavior displayed by newborns are not examples of volitional behavior, since they cannot yet refrain from action. But when infants mature and learn to crawl, to walk, and to play, they start to perform volitional behavior. Their minds do not bring about their movements through mental acts resulting in muscular innervation, nor are they brought about by conjuring up images of kinesthetic sensations they first learn to associate with involuntary movements. Their volitional, goal-directed actions are movements in certain surroundings in which an infant wants, for example, to grasp something, wants to crawl toward something, or tries to obtain something. If they succeed, they have performed a volitional goal-directed action. Hence, in contrast to what Cartesians suppose, infants do not acquire a (separate) mind, the acts of which are capable of bringing about bodily movements. They, as organisms, become self-moving agents able to (try to) perform actions in appropriate settings. Although trying is involved in learning volitional actions (or when doing a volitional act requires some effort), it is misguided to argue (as Hobbes did) that trying is always involved in any and every act.

Goal-directed behavior is an example of volitional behavior if the behavior is controlled by the agent: it exemplifies the power to do or to refrain from doing (this is called a two-way power). Hence if children (and other animals) display a relatively wide range of adaptive behaviors in response to circumstances in pursuit of their goals, we can call them volitional agents. The ability to exercise two-way powers stands in contrast to both involuntary behavior (when the agent does something that is not under his or her control) and non-voluntary behavior (when, for example, the agent does something under duress).

Volitional behavior of children (but also of other animals) is visible in their exploratory behavior, in their capacity to choose between alternative paths, in their recognition of the termini of the phases of phased activities, and in their manifestation of distress and frustration when they fail to obtain what they wanted. Note that, in contrast to, for example, instinctual suckling behavior of newborns, we redescribe their behavior in terms of what they know about things in their environment, what they want to attain, or how they try to attain a certain goal (and what they know in order to achieve this goal). We are then less concerned with the causes of their behavior, as we are in the case of instinctual behavior. Whether infants and nonhuman animals want something is visible in their behavior: they perceive what they want, apprehend an appropriate opportunity for obtaining it, and take steps to get it.

The variety of cognitive-teleological behaviors increases when children get older and master the use of a language. For example, when older children pick up a pencil from the table, it is possible that they are simply removing the pencil from the table, or want to write something, or intend to hand the pencil over to their neighbor, and so on and so forth. In contrast to the other animals, children who have mastered the rules of a language are answerable to what they intend to do because they can give reasons for what they have done, are doing, or are going to do. A reason for action or for belief is a premise in reasoning. Hence it is not causally connected to the action for which it is a reason, just as the reason for a belief is not causally related to the conclusion that it supports. Mastery of a language enables children to specify the reasoning they went through antecedently to acting, or the reasoning they are willing to give ex post actu.

We can ask when children become volitional agents. They become agents exhibiting volitional behavior after the neonatal transition (Hadders-Algra 2018a; Shultz et al. 2018). Early reactions and instinctual behaviors then give way to volitional behavior. This is associated with an increase in cortical control of their eyes, neck, limbs, hands, feet, and vocal abilities.Footnote 1 Here I will discuss some examples of these neonatal transitions. The early side-to-side head turning reaction (or reflex) plays a role in feeding during the early stages of development by having the neonate’s mouth come into contact with the mother’s nipple. This movement is in part guided by stimuli. The areolar glands of mothers’ breasts (the pigmented cells surrounding the nipples together form the areola) secrete chemical compounds which signal to newborns the location of the nipple and, hence, where to find milk (Doucet et al. 2014). This turning reaction gives way to volitional head turning at about 3 months. The hand grasping reaction is replaced at about 4 to 5 months by voluntary reaching and grasping, which are later extended with the pointing gesture (which has a role in the expression of wants; see Bruner 1983; Carpendale and Carpendale 2010). When children begin to use words, they can subsequently ask for what they want (e.g., from "Give" and "Give toy" to "I want toy"). Signaling behavior, such as smiling, is at first noncontingent (often exhibited during sleep; Messinger et al. 2002) and becomes after 2 to 3 months contingent upon the response of caregivers as part of emerging dyadic social interactions. The emerging volitional behaviors are of course adaptive if there is a caregiver present. Caregivers, in turn, are from the beginning of child development not passive spectators. They are interested in establishing eye-to-eye contact, cuddling, touching, and handling children, and respond to the first "coos" of children with infant-directed speech. This creates a setting in which children can learn the effects and meaning of their own actions and passions through the response of their caregivers. Two points are noteworthy. First, infants, as agents, play an active role in discovering their own abilities. By exploring and acting on the world, they learn to control and exploit the link between their actions and their effects on the world, including the social world. Secondly, these actions are learnt volitional behaviors that emerge from and depend on behaviors that were originally spontaneous (for example, they learn that spontaneous kicking movements can be used to move an object in the outside world, resulting in volitional behaviors: they can move objects at will).

It is interesting to add that a similar transition also occurs with regard to perception. The original spontaneous, stimulus-driven form of orienting towards faces (already observed in the first hours after birth), is replaced after approximately 2 months by a socially contingent, volitional form of orienting towards faces. The transitions mentioned above facilitate dyadic interactions: infants begin at 2 to 4 months to engage with others in an interactive, socially meaningful manner involving smiling and cooing. They respond to the changes in vocalization and affect of the caregiver (this is the beginning of turn-taking, conceived as the first form of volitional communication). Empirical studies show that mothers of 3-month-olds display about eight changes in emotion-related facial expressions per minute. It is estimated that an infant is exposed to about 360 changing emotional cues in a single day, which means more than 32,000 between the ages of 3 and 6 months (see Shultz et al. 2018). An interesting experiment illustrating how important these interactions are for children is the still-face procedure (Mcquaid et al. 2009). Mothers are asked to interact normally with their 3- to 5-month-old infant in a face-to-face situation for one or two minutes. The mother is then asked to hold a still face for one minute, and, finally, to resume normal interaction. During the still-face minute infants use smiling as an attempt to draw their mother back in the pleasurable game and, if they do not succeed, appear distressed and frustrated and start crying. Notice that their volitional behavior is explicable in neo-Aristotelian terms: they are pleased if the interaction continues but frustrated if it does not. Hence there is evidence that infants can already anticipate social interactions and are capable of synchronizing activities by means of simple social signals (which are later extended with linguistic expressions).

The Cartesian Roots of the Problem of Knowing Another Mind

Just as there are within the confines of the Cartesian conception two alternative explanations of volitional behavior (Wundt’s innervationist theory versus the impulse theory of James) we can also distinguish two opposing answers to the question of how we can understand another mind: the theory–theory and the simulation view. They both presuppose that we, as observers, cannot identify the mental states of others. This follows directly from the Cartesian conception that the link between mental acts or states and behavior is causal: the behavior or bodily movements are causally connected to invisible mental acts or states that others cannot identify.

Theory–theory states that children, like scientists, learn about the invisible mental states of others by constructing hypotheses about their mental states or experiences. Any ascription of mental states to others involves an inference to the best explanation involving theoretical entities (Premack and Woodruff 1978). It is assumed that, over time, children become experts on mentalizing or mind reading. And when they have acquired this expertise, they tend to "see" things at once, although what they then see is the result of a complex theoretical process. The acquired expertise makes children unaware of the inferential process and makes them believe that their understanding is immediate and non-inferential (Gopnik 1993). An alternative account highlights that this folk-psychological theory of mind is to a large extent innate and results from the maturation of a module (Baron-Cohen 1995).

Simulation theory argues that we use our own mind as a model when understanding the mind of others. Some simulation theorists argue that simulation is "implicit" and subconscious (further explained with the aid of mirror neurons); others like Tomasello argue that simulation is "explicit" and involves the exercise of conscious imagination and analogy with our own experiences.

Neo-Aristotelians have argued that these two accounts are both misguided since they are grounded in the incoherent Cartesian conception of the mind. Their essential criticism was already mentioned: the mind is not invisible and hidden (and merely causally related to bodily movements), but expressed in natural and linguistic behavior (and logically related to behavior). Consequently, it is for conceptual reasons misleading to argue that "folk psychology," involving the use of a primitive theory of mind, enables us to engage in "mind reading." For what is read is not the mind but expressive behavior (even reading is misleading here, for, as Snape taught Harry Potter: "You have no subtlety, Potter.… Only Muggles talk of ‘mind reading’. The mind is not a book"). Why is it mistaken to postulate that children acquire a primitive psychological theory?

First, arguing that children use a theory of mind for predicting behavior, which will in the future be replaced by a genuine scientific theory, creates confusion (Hacker 2001). Of course we use concepts such as belief, desire, pain, and so forth to predict and explain behavior, just as we use concepts of sun and moon ("folk astronomy"), of warmth and cold ("folk thermodynamics"), and of animals, plants, and cells ("folk biology"), to predict, explain, and manipulate natural phenomena. For example, "The sun always rises in the east" is a generalization concerning "folk astronomy," and "Fire makes water boil" is one of "folk thermodynamics." And it is also true that, over time, genuine scientific explanations have replaced some of these generalizations of "folk physics," just as empirical studies have enriched our understanding of, for example, what mental illness is, what the role of genes is in its causation, how we can attempt to cure it, and so on. But it is important to notice that, for example, the transition from "folk thermodynamics" to thermodynamics is linked to a shift in the use of concepts. Physicists no longer use our concepts of "warmth" and "cold" in their explanatory theory. These concepts were first replaced by the concept of "temperature" and temperature was later explained in terms of mean kinetic energy. Yet although the concepts of "warmth" and "cold" are of no use for purposes of thermodynamics, we still use the concepts of "warmth" and "cold" in everyday life, for example, for saying that ice is cold and that a fire is hot. Consequently, arguing (as, for example, Churchland (1988) and Ginsburg and Jablonka (2019) do) that scientific psychology or cognitive neuroscience will replace the concepts of "folk psychology" is misleading if it is meant that scientists will discover that the mental concepts we use are vacuous or empty (such as "intention," "desire," or "will").Footnote 2

Secondly, it is misleading to suggest that neonates, infants, and young children use a "folk psychology" if it is conceived as a primitive theory, because it means that children learn a theory when they learn the use of mental terms. But when neonates perceive their environment, are hungry and thirsty, are frightened, and so on, it is absurd to suggest that they are engaged in theorizing. It is equally absurd to say that infants learn a theory when they are taught to extend their natural manifestations of their sensations, emotions, and wants with linguistic expressions, and when they learn to attribute these mental attributes to others. They are not learning a theory, but rules for the use of mental concepts.

Thirdly, since acquiring the ability to use words precedes understanding descriptions and explanations, arguing that the core of social cognition is acquiring a theory of mind neglects important questions. How do children acquire the ability to use words correctly? What are they doing with words? Answers to these questions require a discussion of the expansion of their vocal powers during the second half of their first year, of how they are taught the rules for the use of psychological words, and of how they learn to do things with words (see Smit 2013, 2014, 2016). Acquiring these abilities enables them to participate in a family and later a group or society. By using these words they can communicate with others about objects, engage in dyadic and triadic interactions, express emotions, sensations, and later thoughts, and so on. Learning the use of mental concepts is learning a form of human behavior (absent in the other animals). These psychological concepts are not imperceptible entities, like genes, electrons, or quarks, for they are not entities at all (nor are they theoretical concepts, such as "inclusive fitness," "entropy," or "voltage"). Saying "Hungry!" is expressing a sensation, "I think that it will rain tomorrow" is an expression of a thought, and by saying "I promise" children make a promise. What we have to explain is how the use of these concepts evolves during development and evolved during evolution as extensions and in part replacements of nonverbal behavior. We also have to explain how children, when they learn to combine words into sentences, acquire the ability to reason and to give reasons (the development and evolution of what Aristotle called the rational psuchē).

The alternative simulation theory attempts to resolve the problems facing the theory–theory account by arguing that we acquire an understanding of another mind without theoretical inference, perspective taking, or running a complex algorithm. Simulation theorists (the philosophers Hume, Smith, and Lipps) and later psychologists such as Harris and Tomasello, argue that psychological attributes are not theoretical or inferential, but simulative and projective. As Goldman (2006, p. 208) summarized this hypothesis:

When seeing a target’s expressive face, an observer involuntarily imitates the observed facial expression. The resulting changes in the observer’s own facial musculature activate afferent neural pathways that produce the corresponding emotion. The emotion is then classified according to its emotion-type and finally attributed to the target whose face is being observed.

The discovery of so-called mirror neurons has been used to underpin the simulation theory. Mirror neurons are neurons located in—among other areas—the premotor cortex. They show heightened activity when someone performs a goal-directed action (or expresses an emotion) and when someone observes a similar goal-directed action (or the expression of the emotion). Hence it seems that apprehension of the mental attributes of others involves mirroring or neural replication. Mirror neurons are said to provide us with knowledge of others by capitalizing on our own motor representations, sensations, and emotions. We gain in this way an understanding of others from the inside. It is a non-volitional, nonreflective, and passively acquired understanding that is subsequently projected on the other.

I will briefly discuss three reasons why the mirror-neuron hypothesis is highly problematic (see further Hickok 2014; Zahavi 2014, Chap. 11; Hacker 2017, Chap. 12). First, since simulative/projective is now replaced by mirroring/projective, the hypothesis rests on the belief that the brain is transforming information—that an observed other has a sensation or is exhibiting purposive action—into another piece of information. Yet this is misguided: I, as an agent, can transform the information that it is raining into the information that I will get wet if I go for a walk outside (I can reason and draw inferences), but there is no such thing as cells or the brain transforming information. It is for similar reasons misguided to argue that the mirror mechanism provides an understanding of the other from the inside, for brains cannot be said to understand anything. It simply makes no sense to explain understanding emotions, sensations, or goals by reference to inaccessible and unknown activities of our mirror neurons. Secondly, it is misguided to argue that mirror neurons aid us in understanding sympathy and empathy, for these emotions are directed at another person. Suppose a child hurts his or her knee. If the mother sees the child’s face contorted with pain, she will rub the injured knee and console and pity the child. Mirroring the child’s sensations does not result in an empathic or sympathetic response. Thirdly, the idea that mirror neurons in the brain "create a bridge" between our brain and the brain of someone else results for similar reasons in hilarious absurdities. This can be illustrated by answering the question of what happens if we encounter someone displaying an emotion that we have not felt ourselves. Mirror neurons cannot help us to realize that others are different from us. Hence, we remain ignorant. In a variant of this misconception it is argued that, although mirror neurons connect brains, we can only see and interpret the other as an extension of us. Keysers (2009, p. 6) argues that mirroring of mirror neurons "makes others become part of us."

The Development of the Rational Psuchē

We have seen that Tomasello (1999), like Descartes, argued that our experiences, which we express by first-persons propositions, are most directly and intimately known to us. Yet how do we know the "content" of our experiences? When I say, "I have a toothache," this seems to be a verbal report of a subjective, mental experience I certainly have. If we deny that it is a report of a subjective experience, then we seem to deny that there is a difference between feeling a pain and the physiological changes occurring when a creature has a pain without having these subjective experiences. In a similar vein: there is an essential difference between merely speaking (or repeating an utterance parrot-fashion) and speaking with thought.

Descartes argued that he could not doubt that he has a pain, an emotion or mood, feelings or thoughts, when he has these experiences. Moreover, he noticed that it seems we cannot make mistakes here: we seem to be absolutely certain.Footnote 3 However, Descartes failed to see that there is another possibility: doubt is here not excluded for epistemic reasons, but doubt and certainty are precluded for logical reasons. Epistemic certainty is acquired if we have excluded or eliminated doubt by giving reasons. By showing that all genuine alternatives in a given circumstance are excluded, doubt is excluded by the available evidence. Descartes argued that a similar reasoning applies to psychological self-ascription (the first-person case). He thought that, since I cannot doubt things to be so with myself, I know with complete certainty that they are so. But the problem with Descartes’ dualism is that there is no separate, mental realm that we can introspect. There is no such thing as excluding doubt in the case of introspection since there is no inner world inhabited with experiences, feelings, sense-impressions, and so on, which we can observe with an "inner eye." Hence the "content" of private experiences can neither be seen by others, nor be seen by me. Consequently, neo-Aristotelians argue, we are not dealing here with epistemic issues. In the first-person case doubt is not excluded because the conditions of certainty are met (as Descartes thought); doubt and certainty are here precluded for logical reasons: our verbal utterances, avowals, and reports of immediate experience have no grounds at all (Hacker 2007, 2013; Wittgenstein 2009). Of course, we can express our experiences, but neo-Aristotelians emphasize that we must not (as Cartesians do) confuse the capacity to say with the capacity to apperceive. Instead of asking the Cartesian question of how first-person propositions are grounded in private experiences, they argue that we should pose a different question: what are the conceptual preconditions for a human being to avow or assert groundlessly how things are with him or her. In terms of developmental science: how do children learn to say how things are with them?

To be aware or conscious of a pain, an emotion or mood, feelings or thoughts, does not belong to the category of introspection, but belongs according to neo-Aristotelians to the category of capacity, in particular to the capacity to say how things are with one. Hence mastery of a language is a prerequisite for acquiring the rational psuchē. For example, children express sensations or emotions in instinctual behavior and later learn to express them with the aid of words and sentences. When they learn a language, they learn to apply psychological predicates to themselves groundlessly (the foundations of these linguistic capacities do not lie in immediate experiences) and to others on the basis of behavioral criteria (e.g., pain behavior in the context of painful stimuli or injury). The essential point to notice is that mastery of the use of the first-person propositions goes hand in hand with mastery of the use of third-person propositions. For example, the transition from instinctual expressions of pain (e.g., facial expressions, cries) to linguistic expressions ("Hurts!" "It hurts!" and then to "I have a pain" and "I am in pain") is bound up with understanding the use of the declarative sentence, "She or he has a pain/is in pain." In learning to verbally express pain, the child also learns to describe others as being in pain: the first-person and third-person pain predications are two sides of one and the same linguistic coin. The capacity of giving verbal expressions is therefore acquired together with, and not antecedently to (as Descartes and much later Tomasello thought) the mastery of the linguistic apparatus for describing the experiences of others. Tomasello, we have seen above, argues that children’s expressions of "subjective experiences" is based on introspection leading to knowledge which children subsequently use to adopt the "like me" stance (as part of trying to understand the mind of another). Hence he discusses the development or emergence of the mind in Cartesian terms. The point to notice is that he nowhere explains how children acquire private knowledge (during ontogenesis), and, importantly, also does not answer the evolutionary question of how hominins acquired insight into their private experiences.

The discussion of the concept of "pain" (or the concept of "will" in previous sections) does not provide us with a template for all psychological predicates, since the rules for the use of mental predicates are different. For example, children learn to answer the question where the pain they have is located in their body, while there is no such thing in the case of an emotion. They learn to specify the object of their emotions (e.g., to explain what they are afraid of), but not of their pain, for sensations do not have an object. These conceptual differences can be further elaborated by investigating the different ways children learn to do things with words. I briefly discuss intention and thinking as examples.

Teaching children the use of "intend" (or "planning") is linked to games in which children have to initiate an act and understand what and why questions posed by their parents ("Why are you doing that?"; "What do you want to achieve?"). By answering these questions, children learn to describe the purpose of their behavior and to justify it. Hence, they must already be able to speak and understand words and sentences. Next, they learn to announce or herald an action ("I am going to V") and learn then that they must go on to V, for that is what they said they were going to do. For example, if a child declares while playing that he is about to throw a ball to another but never does so, he does not yet understand what intentional behavior is. Later on, children learn to give reasons for what they want to do. They form then primitive intentions. Thus the formation of intentions goes hand in hand with learning to give reasons, reasoning, and learning what counts as adequate reasons. When they learn to specify why certain actions are desirable (or permissible or obligatory), they acquire a moral sense. They become then moral creatures who can be held responsible for their deeds. It is important to emphasize here again that learning to use the concept of "intention" is not something that rests on a special source of knowledge. There are, for logical reasons, no sources of information about the self and its workings divorced from behavioral and linguistic expressions that we can observe when interacting or playing with others.

How do children acquire the capacity to believe and think? Neo-Aristotelians emphasize the fact that, as the result of mastering word combinations and later the use of sentences involving a grammar, children become sensitive to reasons. They acquire the ability to reason formally or logically subsequent to having learnt to describe things, for if they begin to understand that sentences are used to describe something, they realize that these can be true or false. And because descriptions (what are called "propositions" by logicians) can be true and can be false, they begin to understand the use of logical connectives since this is bound up with the use of "true" and "false" (if, for example, the sentence "Milk is black" is false, milk is not black). Thus, learning the use of true and false is interlaced with learning to use logical connectives. The use of this simple conceptual network (consisting of descriptions, questions, answers, logical connectives, yes or no, true and false) is, in turn, extended with the concept of logical consequences leading to the first forms of formal reasoning and thinking. The concepts of thinking and reasoning are grammatically interwoven with the use of phrases like "it follows," "therefore," and "so." For example, if milk is white, then it follows that it is not black. Importantly, learning all these concepts is embedded in forms of action (see Baker and Hacker 2009, Chap. 7), in what we call saying the same thing, saying something different, denying what we said, contradicting oneself, and so on. It is interwoven with justifying what we say and do by reference to reasons and reasoning, but also with understanding, misunderstanding, and not understanding. This conceptual network which children begin to master during their third and fourth year is constitutive of their developing ability to reason and think.

When the ability to reason further expands children can also think conditional thoughts, can think of how things are and how things are not, can conceive of general truths, can think of what does and what does not exist, can use modal expressions and counterfactuals. Hence the ability to reason and the use of a tensed language enable children to think of possibilities (to imagine). They start to think about the future and the past; they can think what would happen if …, or what it would be like if …. Because they can imagine something differently, they begin to understand that one can think falsely. Children can then express and articulate thoughts and beliefs and begin to understand that others have thoughts and beliefs. This explains why developmental psychologists have found that children, who can reason and have mastered the use of a tensed language, and so on, can solve linguistic false belief tasks at this age, for they can infer what someone believes given what he or she knows in a certain situation.Footnote 4

This conceptual analysis clarifies an essential difference between the development of learning to express sensations (or emotions) and cognitive development. Children acquire the use of sensation words ("pain") when they learn to extend their natural expressions of sensations with linguistic expressions. If they have mastered their use, we can say that they enjoy a (defeasible) form of authority on how things are with them. Not because the linguistic expressions are descriptions of what the child knows based on introspection, since there is no such thing, but because their truthfulness normally guarantees their truth (and in this sense they can be said to enjoy a form of authority). By contrast, the first-person utterance "I think (believe, hope, expect, suspect, etc.) that p" is not grafted on to natural expressive behavior, but on to forms of linguistic behavior that have already been mastered, namely the use of words and later the assertoric sentence "p." Hence the use of the epistemic operator by children ("I know …") is, in contrast to the use of sensation words, not learnt as a partial substitute for natural expressive behavior.

Since first-person utterances of children like, "I know that …," "I know how …," depend on acquired knowledge (their actual knowledge), we can test what they know and their skills. Suppose a child is capable of solving a nonverbal or verbal puzzle or problem, then the parent will use phrases such as "Well done!" or "How smart of you!" Children learn then that the use of these concepts is bound up with being able to solve problems. They will learn that others (for example older children) may be better at solving certain problems and, hence, that there are different skill levels. The point to notice here is that, when a child says, "How smart I am," he or she cannot be said to enjoy a form of authority comparable to the authority someone has when expressing a sensation or emotion. For the utterance presupposes that someone possesses knowledge and is capable of using this knowledge to answer questions, solve problems, and so on. If a child utters this sentence, it invites hearers to ask some questions, such as about what was the hard problem that was recently solved. By answering these questions, children make clear that they are proud to have accomplished a difficult task or solved a complex problem. Given their accomplishments, children may proudly say that they have talent ("How smart I am!"). Hence uttering this sentence is more like an exclamation.

These examples illustrate that children’s ability to use psychological predicates evolves as an extension and in part replacement of their nonverbal behaviors (expressions of emotions, gestures, volitional actions, and so on) and later as extensions of the use of words and sentences. These abilities emerge during development resulting in—what Aristotle called—the rational psuchē. Yet there is an essential difference between how Cartesians and neo-Aristotelians characterize the emergence of the mind. Since neo-Aristotelians argue that linguistic behavior evolves as an extension of nonverbal behavior (of what Aristotle called the sensitive psuchē, also present in other animals), they do not, as Cartesians do, postulate a separate realm (to which only the owner has privileged access) for understanding the emergence of this new ability. There are not two domains, as Descartes thought, but only one. Aristotle characterized human beings as distinct from other animals and plants by observing what they can do (their capacities). According to Aristotle the psuchē informs a natural body that has life, and this is visible in the exercise of capacities. And since the psuchē is ascribed to living organisms, the capacities that constitute the psuchē cease to exist when the living creature dies.Footnote 5

The Neo-Aristotelian Conception is Not a Variant of Behaviorism or Cognitive Neuroscience

I have discussed the neo-Aristotelian conception of child development as the conceptually sound alternative to Cartesian dualism. In order to remove the possible misunderstanding that the neo-Aristotelian conception is a variant of behaviorism or cognitive neuroscience, I extend my discussion with an explanation of some essential differences.

We have seen that children acquire a rational psuchē when they learn to do things with words. Neo-Aristotelians, just like behaviorists, emphasize that acquiring the early use of language is the result of training. Yet although learning a language is rooted in training, neo-Aristotelians add (in contrast to behaviorists) that children rapidly learn to use words correctly. The point to notice is that the correct use of a word is not a statistical concept, for we distinguish between what is done and what is to be done (just as we draw a distinction between the statement that the chess players are moving their king one square at a time and the statement that the chess king is to be moved one square at a time). The correct use of a linguistic expression is correct in so far as it accords with the rules for the correct employment of that expression. These are the rules that users themselves acknowledge in their explanations of meaning. For example, caregivers teach children the meaning of "red" by referring to a ripe tomato. If a parent points at a tomato and utters the sentence "This  is red," then he or she gives a so-called ostensive definition (a rule). It can be paraphrased as "This color is red" or "This color is called red." The tomato is then used as a sample (a standard of comparison belonging to the means of representation) for explaining what red is and can be used to determine whether other objects in the surroundings are red too. They are correctly said to be red if they are the color pointed at. The functioning of a color sample as a standard is comparable to the role of the meter rule as a sample: saying that the length of a certain object is one meter recapitulates an explanation of what it is for something to be one meter long (namely to be that

is red," then he or she gives a so-called ostensive definition (a rule). It can be paraphrased as "This color is red" or "This color is called red." The tomato is then used as a sample (a standard of comparison belonging to the means of representation) for explaining what red is and can be used to determine whether other objects in the surroundings are red too. They are correctly said to be red if they are the color pointed at. The functioning of a color sample as a standard is comparable to the role of the meter rule as a sample: saying that the length of a certain object is one meter recapitulates an explanation of what it is for something to be one meter long (namely to be that  length).Footnote 6 These standards of correct explanations of words are exhibited in explanations of meaning accessible to observations of behavior (as accessible as showing how to use a meter rule for measuring the length of a stick). They are explanatorily indispensable, since they determine the difference between correct and incorrect use (see further Baker and Hacker 2005, essay 5; Smit 2015).

length).Footnote 6 These standards of correct explanations of words are exhibited in explanations of meaning accessible to observations of behavior (as accessible as showing how to use a meter rule for measuring the length of a stick). They are explanatorily indispensable, since they determine the difference between correct and incorrect use (see further Baker and Hacker 2005, essay 5; Smit 2015).

It follows that misuse of a language (or misbehavior) is determined independently of the description of the causal mechanisms involved in learning, since it is determined by reference to the conventional rules involved. We can ask when, during child development, mere verbal behavior (as behaviorists conceive of linguistic behavior) is transformed into normative behavior. The answer is: as soon as children can ask and answer questions, such as "What is  that?" or "What is this called?" They begin then to understand that it is, for example, correct to explain "red" by pointing at a ripe tomato, but incorrect to point at an unripe one; that tears with a downturned mouth and eyes squeezed shut are a criterion of sadness, but not a constitutive behavioral criterion of anger; that it is correct to attribute "thinking" to someone who is pondering a problem, but incorrect to have the idea that "to think" means to be quiet; and so on and so forth. The capacity of children to use words in accord with norms or rules is visible in how they behave, i.e., in what they do or say. Whether a child possesses an ability is determined by testing whether he or she (1) uses a language (e.g., words) correctly, (2) explains its use correctly, and (3) responds appropriately to its use in context. Thus we can conclude that behaviorists correctly noticed that children are taught the meaning of words by ostensive instruction, yet failed to see the normativity of the instruction and interpreted it causally. Ostensive teaching is not merely ostensive training since it involves the (normative) explanation of linguistic expressions.

that?" or "What is this called?" They begin then to understand that it is, for example, correct to explain "red" by pointing at a ripe tomato, but incorrect to point at an unripe one; that tears with a downturned mouth and eyes squeezed shut are a criterion of sadness, but not a constitutive behavioral criterion of anger; that it is correct to attribute "thinking" to someone who is pondering a problem, but incorrect to have the idea that "to think" means to be quiet; and so on and so forth. The capacity of children to use words in accord with norms or rules is visible in how they behave, i.e., in what they do or say. Whether a child possesses an ability is determined by testing whether he or she (1) uses a language (e.g., words) correctly, (2) explains its use correctly, and (3) responds appropriately to its use in context. Thus we can conclude that behaviorists correctly noticed that children are taught the meaning of words by ostensive instruction, yet failed to see the normativity of the instruction and interpreted it causally. Ostensive teaching is not merely ostensive training since it involves the (normative) explanation of linguistic expressions.

The neo-Aristotelian conception is also not a variant of cognitive neuroscience. Cognitive neuroscientists oppose Cartesian dualism and replace the immaterial Cartesian mind by the material brain: they argue that it is the brain that thinks, perceives, wants, feels, and so on. While neo-Aristotelians argue that it is the organism as a whole (or the human being) that has emotions, thinks, wants, or is conscious, they argue that it is the brain that codes thought and consciousness. And while neo-Aristotelians investigate the development of the mind by investigating how human capacities evolve (i.e., the development of visible or audible behavioral and linguistic expressions of emotions, thoughts, etc.), cognitive neuroscientists believe that we have to investigate the development of thought or consciousness as products of the brain. Since cognitive neuroscientists merely replace Descartes’ immaterial substance (mind) by the material brain, the resulting conception of the mind is called a crypto-Cartesian conception.

If one replaces the mind by the brain while leaving the logical or conceptual structure of the Cartesian conception intact, it is unsurprising that one discusses consciousness or thinking as an emergent quality or property of the brain. But what Aristotle called the (sensitive and rational) psuchē did not evolve as a separate substance, nor did it evolve as an emergent property of the brain. Children can see a flower in the garden and can say what color it is, but this ability is not an emergent property of, and located in, a cell of the striate cortex. Neurons are not doing the seeing (as Crick 1995, p. 104, mistakenly suggests). If a boy has poor eyesight, we observe that he (not his eyes or his brain) has problems in finding his way around (he bumps into things or falls over things and cannot find things by looking, etc.). Seeing is a predicate applicable to the whole, behaving human being using his or her eyes, not to parts (eyes or the brain).Footnote 7 Of course, there may also be emergent properties of the brain. But the behavior of an organism is not an emergent or supervenient property of the brain. That we see with eyes, mean something, or can use our hands to point and to write our name is not a property of the brain.

The discussion of differences between the neo-Aristotelian conception and behaviorism and cognitive neuroscience enables me to answer recent criticism of contemporary philosophers of biology (summarized in Figdor 2018). First, it is said that neo-Aristotelians mistakenly argue that mental concepts are attributed to human beings and to animals that behave like human beings (Figdor 2018, Chap. 5). This criticism is based on a misunderstanding. Neo-Aristotelians do not argue that attributing mental concepts to the other animals is a form of anthropocentrism. They object to Cartesian dualism: neither minds (or brains in the crypto-Cartesian variant) nor bodies behave. Mental concepts are not applied to the other animals because their behavior resembles human behavior, but because they behave: they eat and drink, chase each other, search for food, and so on, and these are not actions or activities attributable to their minds or bodies. We have to observe what animals are expressing in their behavior in order to determine whether mental concepts are applicable to them. Of course, neo-Aristotelians emphasize that there is an essential difference between humans and the other animals: only humans use a language and can therefore also express their emotions, sensations, and so on, in linguistic behavior (humans alone possess a rational psuchē). In animals the limits of what they can express are set by what they can express in nonverbal behavior, whereas in humans these limits are set by what they can express in nonverbal and linguistic behavior. Secondly, it is argued (Figdor 2018, Chap. 5, note 5) that, since neo-Aristotelians argue that behavioral manifestations and linguistic expressions, avowals, and reports are constitutive behavioral criteria for applying mental predicates, individuals suffering minimal consciousness are clear counterexamples, for they do not manifest and express their emotions and thoughts. This is another misunderstanding. It is true that neo-Aristotelians emphasize that capacities, characterizing the mind, are in normal conditions visible in what organisms do (their behavior), since activities are logically prior to potentialities. The exercise of potentialities is characteristic of an organism (not of the mind, brain, or body). However, there are causal explanations (like a car accident leading to lesion of the corticospinal tract) clarifying why these potentialities are not actualized. Locked-in syndrome is an example and is characterized by mutism and quadriplegia.Footnote 8 Hence, there are obvious causes why these patients cannot express anything. Yet, like patients in a vegetative state, they are still human beings, not plants. Lacking the actuality to express their thoughts does not transform them into plants, for they, as humans, in contrast to plants, have the potentiality to express them.Footnote 9

There is an important lesson to draw from my discussion of how acquiring the use of a language frees children (and freed our ancestors during the course of evolution) from the constraints imposed by genetic evolution. We have seen that if children understand the rules for the use of linguistic expressions, they can do things with words (e.g., express emotions and later thoughts). These rules are, just like the rules of chess, autonomous. They are not grounded in human nature (encoded in our genome) and only support each other, resulting in a free-floating network of concepts that is constitutive of linguistic behavior. For example, if children understand an ostensive definition, then they can do something with the definiendum: they know how to apply the definition. There is an internal (or logical) relation between understanding the explanation of an ostensive definition and the application. Understanding the definition is grasping that relation (i.e., grasping what counts as applying the definition correctly). If a child cannot explain that this object has that color, then he or she does not speak with full understanding. In a similar vein: if a girl expects it to rain tomorrow, then she knows that tomorrow's rainfall will satisfy her expectation. If a boy intends to take an umbrella with him when he goes for a walk, then he knows that his intention will be executed only by taking an umbrella with him. There is an internal relation between expecting something and knowing what will satisfy one’s expectation, and between intending and knowing what will fulfil one’s intention. Thus neo-Aristotelians argue that an internal relation, in contrast to what philosophers of biology believe (see, e.g., Hannon and Lewens 2018; Ginsburg and Jablonka 2019), is not mediated by a third thing (i.e., an interpretation, hypothesis, generalization, mental or brain state, and so on).Footnote 10

Understanding the (conventional) rules for the use of mental concepts is the beginning of the development of the rational psuchē during child development (and marked the shift from natural to cultural selection during the course of evolution). It enables children to express their emotions, wants, thoughts, and so on with the aid of mental concepts. Since these rules are understood by others, they can engage in linguistic communication. The internal relation between explanation and application of mental concepts clarifies why we use our concepts without referring to genes or brain processes. As Darwin scribbled in his 1838 notebook "M": "A person might be quite familiar with thought & yet be ignorant of the existence of the brain."Footnote 11 For language freed humans from dependence on genetic evolution.

Conclusion

I have discussed two presuppositions of the Cartesian conception and argued that they lead to unresolvable problems, because they are grounded in an incoherent conception of mind and body. It is incoherent to argue that mental acts or events cause volitional behavior, and that we observe only bodily movements and need to postulate a theory of mind for understanding the invisible mind. According to neo-Aristotelians, the questions posed within the confines of the Cartesian framework do not make sense, either in developmental science, or in evolutionary science. Hence it is, according to them, time for a change in the explanandum. What we have to explain, in terms of the neo-Aristotelian conception, is how on top of the vegetative and sensitive psuchē, in humans alone the rational psuchē evolves during development and evolved during evolution. That requires having to study how the ability to do things with words emerges when children learn to participate in the normative practice of using words and later sentences, for doing things with words leads to an expansion of their mental powers.

We have seen that the ideas of James and others about the role of mental acts and events in voluntary movements were not based on, or informed by, empirical observations (of mental acts, events, etc.). We have also seen that the ideas of developmental psychologists on inferences, mind reading, simulation, mirroring, and projection were not based on empirical research either. This raises a question: why did they postulate these alleged mental acts, states, images, inferences, simulations, and so on in the first place? The neo-Aristotelians' answer to this question is simple: they postulated these mental phenomena as a response to the demands of the Cartesian conception. Cartesian dualism leads to the idea that there must be mental phenomena, that there must be a self or "I" that initiates movements, processes data, and computes meaning. Yet, neo-Aristotelians argue, this is only a Cartesian picture, not a scientific theory. Consequently, the hypotheses constructed in response to the demands of the picture are not testable hypotheses, for they are not hypotheses at all. Neither the innervationist theory of Wundt and others, nor the impulse theory of James, can be improved in such way that better arguments enable us to conclude that the problem of how the "I" initiates and guides acts of will has been solved. A similar reasoning applies to the theory–theory and simulation account. The conclusion we can draw is that the acts of will postulated by James and others, and the inferences and simulations postulated by developmental psychologists, are merely illusions, for the Cartesian conception of the intellect and will is incoherent.

Notes

It is interesting to notice that instinctual behaviors and early movements are modulated by the subplate neurons (Hadders-Algra 2018b; Kostović et al. 2019). The transient cortical subplate phase ends at 3 months post-term when the permanent circuitries in the primary motor, somatosensory, and visual cortices (begin to) replace the subplate. The subplate gradually disappears in the remainder of the first year as the result of apoptosis.

Contrary to what Churchland believes, physicists have not found that our use of the concepts "warmth" and "cold" is vacuous, although they have found that the concept of "caloric" (to explain heat) is empty, just as the concept of "phlogiston" (to explain oxidation) proved vacuous.

James (1950, vol. I, p. 188) argued, in contrast to Descartes, that reporting on one’s experiences is fallible: "And as in the naming, classing, and knowing of things in general we are notoriously fallible, why not also here?" He concluded "that introspection is difficult and fallible; and that the difficulty is simply that of all observation of whatever kind." Neo-Aristotelians challenge the Cartesian presupposition that the putative (in)fallibility is a fact of nature.

False-beliefs tasks investigate whether children understand that others have beliefs and thoughts other than their own. In the well-known Sally and Anne test, a story is told to children with the aid of two puppets, Sally and Anne. Sally takes a marble and hides it in her basket. She then leaves the room and goes for a walk. While she is away, Anne takes the marble out of Sally's basket and puts it in her own box. Sally is then reintroduced and the child is asked: "Where will Sally look for her marble?" Ben-Yami et al. (2019) have argued that 3-year-old children have problems with understanding this task because the difference between "Where will Sally look" and "Where should Sally look" is not yet clear to them.

Neo-Aristotelians emphasize that humans are not minds united to a machine, but, like other organisms, complex thermodynamic systems that evolved into language-users (Smit 2018). Organisms are open thermodynamic systems that have acquired a metabolism and hereditary replication. Metabolism involves a coordinated system of chemical reactions contributing to its maintenance, i.e., a system that imports energy to maintain order (e.g., DNA repair, regeneration, but also to grow, reproduce, etc.). Hereditary replication involves a system of copying in which the new structure resembles the old. Organisms evolved from simple organisms like a cell to complex multicellular organisms like plants, animals, and humans. We can characterize these different forms of life by reference to their powers, which can only be studied by investigating the behavior of organisms, for activities and actions are logically prior to potentialities.

The incorrect use of expressions (e.g., saying "This tomato is blue" when pointing at a ripe tomato) must not be conflated with the nonsensical use. For example, "Red is a sound" is not incorrect but nonsensical, for the word "red" can be associated with words such as "glossy" or "matte," but not with the words "loud" and "soft."

It is interesting to mention the ultimate explanation of locked-in syndrome. In humans, motor control became increasingly corticalized: the number of cortical motor neurons increased more than the number of neurons in the spinal cord (Herculano-Houzel et al. 2016). For example, in relatively small primates the ratio between cortical motor neurons and spinal neurons is about 2:1, whereas it is about 20:1 in humans. Locked-in syndrome illustrates one consequence of the expansion of cortical control. In small primates such a lesion causes only a loss of fine motor control in the upper limbs, whereas the motor control of the rest of the body remains intact.

Some patients recover to a certain extent, and it is an interesting question what the cellular processes are that enable them to recover, since cellular processes (cell division, migration, differentiation, apoptosis, etc.) facilitate (the development of) behavior at the level of the organism (see further Kirschner and Gerhart 2005; Smit 2014, 2018).

When we cool a room by opening the window on a summer day, the opening of the window is a mediating, external cause, but there is no such thing in the case of understanding a language, for it is akin to an ability (i.e., a potentiality, not a mental or brain state, which are actualities). Yet brain processes are of course a causal condition for possessing and executing the ability.

However, Darwin, like many others, did not realize that first-person expressions, avowals, and reports of mental phenomena are noncognitive utterances. In "M" (and his later work) he could therefore not resolve the question why it is confusing to say that "Thought is only known subjectively ((??)) the brain only objectively." For that requires understanding that experiences, thoughts, and so on are not subjectively known. And because Darwin presupposed that we cannot have the subjective experiences of another, he gave in "M" the wrong answer to the question of how children acquire an understanding of another mind: "We cannot perceive the thought of another person at all, we can only infer it from his (its) behaviour."

References

Baker GP, Hacker PMS (2005) Wittgenstein: meaning and understanding. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Baker GP, Hacker PMS (2009) Wittgenstein: rules, grammar, and necessity, 2nd edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford

Baron-Cohen S (1995) Mindblindness: an essay on autism and theory of mind. MIT Press, Cambridge

Bennett MR, Hacker PMS (2003) Philosophical foundations of neuroscience. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford

Ben-Yami H, Ben-Yami M, Ben-Yami Y (2019) What does the so-called false belief task actually check? PsychArchives. https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.2513

Bruner J (1983) Child’s talk: learning to use language. Norton, New York

Candlish S (1995) Kinästhetische Empfindungen und epistemische Phantasie. In: von Savigny E, Scholz OR (eds) Wittgenstein über die Seele. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, pp 159–193

Carpendale JIM, Carpendale AB (2010) The development of pointing: from personal directness to interpersonal direction. Hum Dev 53:110–126

Churchland PM (1988) Matter and consciousness, Revised edn. MIT Press, Cambridge

Crick F (1995) The astonishing hypothesis: the scientific search for the soul. Touchstone, New York

Doucet S, Soussignan R, Sagot P, Schaal B (2014) The secretion of areolar (Montgomery's) glands from lactating women elicits selective, unconditional responses in neonates. PLoS ONE 4:e7579

Figdor C (2018) Pieces of mind: the proper domain of psychological predicates. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ginsburg S, Jablonka E (2019) The evolution of the sensitive soul: learning and the origins of consciousness. MIT Press, Cambridge

Goldman AI (2006) Simulating minds. Oxford University Press, New York

Gopnik A (1993) How we know our minds: the illusion of first-person knowledge of intentionality. Behav Brain Sci 16:1–14

Hacker PMS (1996) Wittgenstein: mind and will. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Hacker PMS (2001) Eliminative materialism. In: Schroeder S (ed) Wittgenstein and contemporary philosophy of mind. Palgrave, Basingstoke, pp 60–84

Hacker PMS (2007) Human nature: the categorial framework. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Hacker PMS (2013) The intellectual powers: a study of human nature. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester

Hacker PMS (2017) The passions. A study of human nature. Wiley, Chichester

Hadders-Algra M (2018a) Early motor development: from variation to the ability to vary and adapt. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 90:411–427