Abstract

Families have a right to privacy, but we know little about how the public–private boundary is negotiated at the micro level in educational settings. Adopting ethnomethodology, the paper examines how talk about the home situation was occasioned and managed in ten parent–teacher conferences in early childhood education and care (ECEC), with a special focus on the ECEC teacher’s strategies for eliciting family information. The paper demonstrates a continuum of interactional practices which, in various degrees, make parents accountable for providing family information. The analysis shows that parents both volunteer and provide the pursued information, thus actively orienting to the norm of visibility in child rearing. However, although both parties orient to questioning and fishing as business as usual, the parents’ accounts sometimes had an excusing quality or they adopted a reserved communication style, suggesting a certain ambivalence as well. The paper outlines different ways of understanding the present partnership ideal in parent–teacher teacher cooperation with implications for the negotiation of privacy. The paper also addresses training, which can contribute to staff and student reflections on the management of the public–private boundary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Norway, almost all preschool children attend kindergarten, and parents and staff are expected to cooperate in the best interest of the child (Framework Plan for Kindergartens, 2017: 29). Parent–teacher conferences, usually offered twice a year, are one arena in which this kind of cooperation is realised. In Markström’s ethnographic study, such conferences are described as constructing a “picture of the child, the institution and to some degree even the home environment” (Markström, 2005: 121 (the author's translation from Swedish)). In parent–teacher conferences at kindergartens, parents receive information about their child, but information also goes the other way around, i.e., family information about the child and/or their home situation is provided to an early childhood education and care teacher (hereafter referred to as teacher), which is the topic of this paper.

In an interview study, 60% of nursery teachers reported that they had sufficient information about a child’s home situation, while around 40% were less certain (Drugli & Undheim, 2011: 56). In this study, an informant asked: “How much should we know? If there are problems at home, we should know about them, so we can take good care of the child. Otherwise, I’m not sure that we need to know very much” (Drugli & Undheim, 2011: 56 (the author's translation from Norwegian)). From a moral and legal perspective, this citation displays an ambivalence which can be formulated as a potential conflict between the family’s right to privacy and a child’s right to proper care (UN Convention on the Rights of the Child).

According to Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), privacy is a human right: “Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence”. In accordance with the integrity perspective, individuals have a right to manage themselves without outside interference, (Alf Petter & Njål, 2010: 99). However, privacy is not an unconditional right, and the family can be viewed as both a unit and as conflicting parts (Alf Petter & Njål, 2010: 105). The second paragraph in Article 8 states exceptions that are “necessary in a democratic society,” for instance, “for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others”. Thus, in an ECEC setting, children’s rights, and especially the principle of the best interest of the child (UNCRC, Article 3), may conflict with the family’s right to privacy as a group.

In ECEC research, the dichotomisation between “public” and “private” has been understood as a threat to children’s citizenship (Østrem, 2008) by discouraging teachers who suspect child neglect from contacting the child welfare service (this is an obligation in accordance with Section 46 of the Kindergarten Act). In Norway, the number of child welfare notices has increased significantly in recent years, and the findings from a transnational research project indicate that Norwegian child welfare workers are more willing to intervene in the family (Oltedal & Nygren, 2019). Seen from this angle, information about a child’s home situation is also a display of parenting skills, living conditions, etc. that welfare state agencies can monitor and police (Donzelot, 1980). Questions about a child’s home situation may, at least to their parents, have a potential power dimension, and there is a lack of research about how teachers manage such topics during parent–teacher conferences.

The concept of privacy has various dimensions (physical, psychological, social and informational; see Leino-Kilpi et al. (2001)), and this study mainly investigates the social dimension of the concept, addressing participation in interaction (Leino-Kilpi et al., 2001: 666). Inspired by ethnomethodological conversation analysis (EMCA), the paper investigates how family information is occasioned or “talked-into-being” in ten audio-taped parent–teacher conferences by asking the following questions:

What interactional strategies for eliciting family information do ECEC teachers adopt in parent–teacher conferences and how do parents respond? What embedded understandings regarding the norm of privacy are thereby displayed?

Not unexpectedly, the analysis shows that the teachers use the available interactional resources, mostly questions. After briefly outlining the broader educational context, major findings from conversation analytic research on inquiries will be presented. In the Results section, the range of interactional practices at work in the material will be demonstrated, and some elements will be reflected upon in more detail in the Discussion section. While the historical backdrop of the growing institutionalisation of childhood can be taken to suggest that there has been a dissolution of the boundary between the private and the public, including boundary work in micro-sociological settings, this analysis suggests otherwise.

ECEC at the Intersection of the Private and the Public

The right to privacy seems to presume a private domain separate from other people and state authorities, which could be easily associated with the nuclear family and the “housewife family” ideal which developed (and declined) during the 1900s. This ideal, pinpointed by Lasch as “the family as a haven in a heartless world” (Lasch, 1976), was founded on a strong separation between public and private life (Lasch, 1976: 44). However, as a social democratic society, Norway has followed a defamiliarizing family policy, nurturing women’s economic independency (Ellingsæter & Leira, 2004: 24), in line with general individualising tendencies in Western societies. These tendencies have also affected both children and upbringing practices, and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) in particular manifested an ideological shift from the family to the child as an independent third party (Wyness, 2014). The institutionalisation of childhood was increasingly intensified, gradually including toddlers as well as young people (Thuen, 2008: 206). In this ‘public family’ policy (Hernes, 1987) children underwent what Dencik (1999) called “double socialization” in private and public arenas. Consequently, parent–child relations have become more transparent (Dencik, 1999: 252) to state agencies, suggesting a norm of visibility (Alasuutari et al., 2014: 97).

On the micro-level, this development suggests a normative shift in how professionals and parents are supposed to relate to one another in educational settings (where ECEC represents the first step in the chain of lifelong learning). Instead of the idea of separate domains, an understanding of a so-called “shared responsibility” has developed in ECEC (Framework Plan for Kindergartens, 2017: 29). This means that teachers have a broader responsibility for children’s well-being while enhancing parental involvement (Persson & Broman, 2002). In the OECD report Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care (Organisation for Economic & Development, 2006), ECEC staff are advised “to form a partnership with parents, which implies a two-way process of knowledge and information flowing freely both ways”. The Norwegian ECEC framework plan outlines the parent–staff relationship using somewhat similar wordings:

The kindergarten shall facilitate co-operation and good dialogue with the parents. (…) At an individual level, the kindergarten shall ensure that the parents and the kindergarten can regularly exchange observations and evaluations concerning every child’s health, well-being, experiences, development and learning (Framework Plan for Kindergartens, 2017: 29).

Questioning is not specifically mentioned in the framework plan (“exchange observations and evaluations”). In Markström’s (2005) study, teachers tended to avoid questions about the home, though they had different personal styles in this respect. Some teachers adopted a more telling style, while others adopted a question–answer style (Markström, 2005: 125).

Fairclough (1992) describes a development whereby the interaction in more and more institutional settings is characterised by a hybrid genre, mixing everyday and institutional discourse. Within a Foucauldian framework, welfare state professionals represent contemporary versions of the Christian pastor figure (Foucault, 2007: 143), and dialogue is a technology that is used to govern individuals (Karlsen & Villadsen, 2007) and families (Donzelot, 1980). It is more likely that privacy is easier to maintain in a formal institutional context where people are in a “frontstage” (Goffman, 1959) mode than in an informal setting (Burgoon, 1982: 222).

An ECEC parent–teacher conference, characterised by much laughter (Alasuutari, 2009), represents the latter. Thus, the interaction style is not designed to maintain a public–private boundary. The discourse analytic perspective has been much adopted in Nordic research on parent–teacher conferences (Alasuutari & Markström, 2011; Dannesboe et al., 2018; Markström, 2011), included in Markström’s (2005) study. Markström describes how teachers’ “innocent questions” (what kind of books children like to read) can be understood as a soft way of governing the conduct of the family (Markström, 2011: 68), in this case, guiding parents to facilitate reading.

However, Markström’s ethnographic approach is primarily targeted at describing the overall context of the conferences (Markström, 2009), and the data extracts were not accurately transcribed. As a consequence, the very processes of “questions and answers” (Markström, 2009: 129) and how the visibility norm is managed in social interaction remain opaque. In contrast, the ethnomethodological tradition of conversation analysis (CA), introduced in the next section, can provide an in-depth account of the inherent power aspect of questioning.

The Power of Questioning

In the ten parent–teacher conferences examined in this paper, the most common way of seeking information was, not unexpectedly, asking questions. A question may be understood as: “a form of social action, designed to seek information and accomplished in a turn of talk by means of interrogative syntax” (Heritage, 2002: 1427). However, as will be demonstrated in the Results section, there are also less direct ways of seeking information, for example, fishing for information without using interrogative syntax (Pomerantz, 1980). Across institutional settings, professional inquiring is a recognisable activity (Linell et al., 2003: 542) and a primary means to “determine truth and amass facts” (Tracy & Robles, 2009: 135). In addition, professionals’ questions may be “drenched with implicit moral judgements, claims, and obligations” (Heritage & Lindstrom, 1998: 398), effectuated through the apparatus of talk.

In ethnomethodological conversation analysis, questions and answers are prime examples of ‘type-connected’ two-unit sequences in talk (Sacks, 1987; Schegloff & Sacks, 1973). After a ‘first-pair part’ (the question), a ‘second-pair part’ (the answer) can be expected. Since the question, so to speak, induces addressed respondents to produce the expected second-pair part (Schegloff & Sacks, 1973), the “adjacency-pair” apparatus gives the questioner a momentary power (Wang, 2006). While the inherent power or control dimension of questioning is seldom addressed in CA studies, Harvey Sacks, a central founder of the discipline, did in one of his studies “As long as one is in the position of doing the question, then in part they have control of the conversation” (Sacks, 1995: 49f). This means that the questioner is in a position to control the turn-taking (the next speaker) as well as the topic/agenda of the next turn (Sacks et al., 1974; Schegloff & Sacks, 1973; Wang, 2006: 533). Moreover, the power of the questioner (and the respondent’s accountability) can be intensified through the use of multiple questions, for instance, a “questions cascade” producing different versions of the same question (Clayman & Heritage, 2002b: 757) or “follow-up questions” pursuing a more substantial answer (Clayman & Heritage, 2002b: 756–758). However, the power can also be softened by adopting prefaces and accounts in the question design (Steensig & Drew, 2008: 12).

Obviously, power is not referred to here in its absolute sense, literally “forcing” respondents to provide information, yet accountability as “good parents” (and “good professionals”) might nevertheless be at stake. From an ethnomethodological perspective, “not answering the question” is less of an option. Of course, we can imagine parents who refuse to answer questions in a conference, but given the adjacency-pair apparatus (Sacks, 1987; Schegloff & Sacks, 1973), where a question establishes a normative expectation of an answer, a deviance from expected conduct represents a “noticeable action,” calling for an account of why the second-pair part is not produced (Heritage, 1984).

Regardless of role, the normative pressure, embedded in the adjacency-pair structure, represents a situated power on behalf of the questioner and, as mentioned, parents may also ask questions in an ECEC conference. Ultimately, interactional roles are deeply intertwined with institutional roles. As previously mentioned, teachers have a legal obligation to monitor a child's well-being and contact the child welfare service if child neglect is suspected. This structural power might, at least indirectly, affect how parents behave in ECEC conferences.

Method

The data comprise 10 audio-recorded parent–teacher conferences collected from two kindergartens in Southern Norway (2016–2017) in a qualitative research project dealing with parent cooperation and diversity in ECEC. The project received funding from the University of Southeast-Norway and the Oslo Fjord Fund. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data and was conducted in accordance with the Norwegian National Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences, Humanities, Law and Theology (NESH, 2019).

The two kindergartens differed in terms of size and cultural diversity. In kindergarten 1 (see Table 1 below), located in an urban environment, two ECEC teachers and six parents participated in the study. The parents in kindergarten 1 were from an immigrant background, and in three of the conferences, a multilingual assistant who worked at the kindergarten was present to interpret and assist (conferences 1, 5 and 6 in the table). Kindergarten 2 was a small kindergarten located outside the city centre and all the parents were from a majority background. In kindergarten 1, the researcher was present at the conferences but only played a minor role. In all the conferences, the teachers followed a form, structuring their reporting about the child in question (see Alasuutari & Karila, 2010), but the analysis in this paper does not focus on how the form contributes to organising the interaction, which would have required video data.

The data extracts were transcribed according to the conversation analysis convention, originally developed by Gail Jefferson (ten Have, 2007). Information about institutional roles and parents’ minority/majority status will be provided in the transcripts (“minority/majority mother”), which is a controversial issue in conversation analysis (ten Have, 2007: 97f.). However, the sociocultural background and reflections on privacy will mainly be discussed after the conversation analysis. Moreover, in order to preserve the anonymity of the informants, some background information may have been changed.

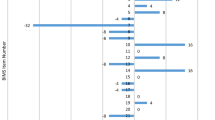

In the analysis process, the teachers’ eliciting actions were identified and coded to identify patterns. As can be seen from the table above, the material had a total of 109 instances of inquiries, 69 of which dealt with the home situation. Regarding content, the questions addressed the child’s eating, sleeping, toilet, playing and dressing habits at home, language code and reading, crying and the use of a dummy, older siblings, and other persons living in the household. The table shows that teacher A asked the vast majority of the 69 questions addressing the home situation. The teachers also asked 40 questions relating to other topics than the home situation. For instance, the parents’ views about the contact with the staff, their child’s well-being at kindergarten, whether they had received certain information or permission to perform language tests, etc. All teachers (A/B/C) asked these kinds of questions, dealing with various aspects of the services.

Inquiries work both ways, and some of the parents in this study also asked questions (not shown in the table). The parents asked a total of 33 questions, many of which were about their child’s conduct in kindergarten. Thus, Markström’s finding that parents asked more questions than teachers (Markström, 2005: 122) could not be confirmed. In addition to questioning, the practice of fishing for information (Pomerantz, 1980) as well as parents’ unelicited reports from the home situation, were also noted and coded.

In terms of generalisation, the study cannot confirm how usual it is to ask for family information in this setting. After all, in her study, Markström stated that direct questions about the home were “rare” (Markström, 2005: 139). The same applies to two of the three teachers in this study, whereas one of the teachers (teacher A) asked a lot of questions. Regardless of the distribution of eliciting practices, this paper will demonstrate, in Peräkylä’s wording: “Social practices that are possible, i.e., possibilities of language use (..)” (Peräkylä, 2004) in this setting. Thus, rather than focusing on frequency, the paper will demonstrate a range of practices for managing family information.

Results

This section examines various ways of managing home information in ECEC parent–teacher conferences. The analysis is organised in such a way as to demonstrate a continuum of teachers’ eliciting actions and their ability to affect parental accountability in the talk, i.e., the analysis will demonstrate increasing interactional pressure on the parents to provide family information. The first extract shows a practice called “Parents’ spontaneous comparisons” in which parents volunteer family information that is not being sought by the teacher (extract 1). Extract 2 demonstrates the rarer strategy of fishing for information, and extracts 3 and 4 investigate the teachers’ questioning practices.

Parents’ Spontaneous Comparisons

Parents’ “spontaneous comparisons,” revealing family information not (yet) pursued by the teacher, were a common resource for bringing information about the home into the ECEC conference. In this practice, the parent sticks to the topic under discussion (the child X’s conduct in ECEC) but makes a topic transition into the home setting on the same topic (the child/family X’s conduct at home). (The teacher would sometimes use this practice as a resource to ask elaborating questions, as in this extract). In this extract, the teacher talks about the kindergarten’s reading group, before the mother self-selects:

The turn allocation system described in conversation analysis suggests that usually, one party speaks at a time (Sacks et al., 1974). In line 2, the mother self-selects, and there is a moment of overlapping talk where the mother recycles part of the teacher’s turn (“She loves it”). Rather than completing the teacher’s turn (Lerner, 2002), the mother’s recycling starts a new project, describing their reading practices at home before the child’s baby sister was born. While momentary overlapping around anticipated turn endings does occur in talk, second speakers rarely persevere after the drop point (“loves it”), which can be interpreted as competition for the floor (Schegloff, 2000: 35). The mother’s recycling in line 2 can thus be heard as (friendly) claiming independent access to knowing what her daughter loves, but in line 6 she is also making an excuse about why they do not read as much at home anymore, indicating a certain defensive orientation on the part of their reading habits.

In this extract, privacy is not disturbed as the mother is not required to provide family information, but she does anyway. The example is representative of the overall material, and the practice of making a spontaneous comparison is likely to be seen as a symptom of the visibility norm associated with modern parenthood (Alasuutari et al., 2014; Dencik, 1999). This norm might induce parents to display appropriate/reflected parenthood (the mother has been reading to the child) and/or invoke excuses and accounts (Scott & Lyman, 1968) when the highest standards cannot be met (the mother no longer has time due to the new baby). It is possible that the defensive orientation can also be related to what previous research on minority parents has described as “enhanced awareness” of parenting practices (Smette & Rosten, 2019). With language code and reading as a topic, the mother would perhaps expect to be asked about reading at home. Thus, anticipating the upcoming topic (reading habits at home) could be an interactional strategy to portray herself as a good parent.

Fishing for Family Information

The next extract demonstrates an indirect information-seeking strategy, described in Anita Pomerantz’s (1980) seminal paper: “Telling my side: “Limited Access” as a “Fishing” Device”. In her example, a caller with “limited” knowledge can fish information about an event from a person with authoritative access. The line: “I wz trying you all day.en the line wz busy fer like hours” might be perceived as a report of an experience or as a careful request to volunteer information (Pomerantz, 1980: 187). If the missing counterpart is not produced, this might be perceived as a form of “withholding” (Pomerantz, 1980: 196).

In extract 2, below, the teacher adopts the fishing device to elicit family information, more specifically, information about why the child, Adrian, was absent from kindergarten the week before. On this particular day, the teacher says that she had walked with a group of children through the garden at Adrian’s house:

In the middle of line 1, the teacher switches over to direct reported speech (“We can go through at Adrian and see whether he’s at home”), but it is not clear whom she is animating. She is most likely animating her own thinking at this moment. This animating voice prevails in line 3, but the talk now refers to a talk with Adrian (“then he had been with”), where the child had mentioned reasons for his whereabouts on this day (“grandmother? (..) No, grand- “). Again, it is not clear whether the confusion about the child’s whereabouts is part of the reported scene (the child not being sure about his whereabouts), or whether the teacher has problems recalling what the child had said. In either case, the teacher has, in Pomerantz’s (1980) terms, “limited access” and the parents are the best source of authoritative information.

In this extract, both parents align to bring up “the missing counterpart” and in line 4, the mother takes a leading role and addresses the father who, in line 5, gives a tentative answer. However, in line 9, the mother provides the correct information herself: they had been at the eye specialist in the neighbouring city. In line 11, she says, “So that’s why we were off- = Took some time,”, and this phrase explicates the teacher’s project of gaining an account of their whereabouts on this day. Compared to the direct questions described in the two next sections, the fishing strategy makes the parents less accountable for providing the “requested” information. In another instance in the same conversation (not shown), the parents did not volunteer family information. Thus, this strategy gives the parents a choice: whether to provide or withhold the pursued information.

In terms of privacy, this instance likely represents only a minor disturbance, which the parents could have avoided reacting to. Nevertheless, their willingness to fill in the missing pieces supports the presence of a visibility norm in child-rearing (Alasuutari et al., 2014; Dencik, 1999). The parents managed to convey that they had very good reasons (the eye specialist) for why Adrian did not attend kindergarten on this day, precluding alternative scenarios that may have occurred to the teacher.

Asking for Family Information

In extract 3, below, the common sequential structure “contextualizing talk + question + answer” will be demonstrated. “Context” is understood here in Heritage’s two-fold account of actions as both shaped by preceding actions and as context-renewing, producing new actions (Heritage, 1984: 242). Regarding the first dimension (actions as context-shaped), questions are seldom asked “out of the blue”. Rather, professionals tend to produce some kind of “prefatory statements” (Heritage & Clayman, 2010: 218), which contribute to “contextualizing” the upcoming question (Clayman & Heritage, 2002a: 193) and thus “explain” the reasons for the question. In ECEC, this often takes the form of the teacher accounting for how the child is doing in the ECEC along various parameters, and this kind of reporting/describing is the dominant activity throughout the conferences. The teacher then makes a transition into the home setting on the same topic. (In other words, a spontaneous comparison with the home-setting, this time initiated by the teacher).

Earlier in the talk, the teacher in this extract had been describing the child’s playing skills. In line 19, she switches to talking about the child’s motor skills in kindergarten, which makes up the context for the question in line 21 (“I don’t know whether you hike and such like?”):

The change in topic is basically indexed through the keywords “motor skills, sensing” in line 19, which possibly reflects topics in the form structuring the meeting agenda. An evaluating description of the child follows, ending in the assessment “She really loves walking”. In ordinary conversations, assessments of this kind make a subsequent assessment relevant (Pomerantz, 1984), but through the minimal response in line 20 (“mm”), the mother positions herself as the receiver of a report rather than an assessment. In line 21, the teacher continues the accounting, and the turn ends with a question: “I don’t know whether you hike and such like?”. The preface “I don’t know” signals a low epistemic gradient on behalf of the teacher, framing the matter as outside her domain of knowledge. The tag “and such like” performs the same function. The mother responds to the question in lines 22–24 but does not elaborate much and speaks in a very low voice (“°Sometimes°”).

Compared to extracts 1 and 2, the mother in this extract did not appear to be very talkative, though her conduct can easily be interpreted as an example of what Burgoon called reserve, which “implies some degree of interaction with others and refers to the manner in which one communicates as to limit others’ knowledge of oneself (Burgoon, 1982: 221). The structure (contextualizing talk + question + answer) is nevertheless representative of the overall material. In the rest of the extract (not shown), the teacher uses the fishing strategy to get a more substantial answer to whether the family hikes. Another strategy for the teacher to map the family’s lifestyle on this matter would be to pursue the topic more directly by asking elaborating questions, which takes place in the last extract in the next section.

It is perhaps not so easy to argue that a question about hiking habits represents a potential disturbance of privacy. However, a major survey revealed that many patients considered a question about their use of leisure time during medical consultations to be a violation of their privacy (Parrott et al., 1989). Thus, regardless of the setting, lifestyle questions about hiking habits might invoke moral feelings, but they are probably more expected and justified in a medical setting. Information about the family’s hiking habits contributes to filling in “the picture of the child” (Markström, 2005: 122). However, it is hard to see the necessity of the question. As in extract 2, the teacher may have other reasons for asking the question (for instance, curiosity) rather than a professional need to know.

Asking Multiple Questions

Professionals often ask clustered or “multi-unit questions” (see Linell et al., 2003 for an overview). Overall, in these data, there were not many questions, but one of the three teachers (teacher A) asked many questions about the home situation. In a sequence from one of the conferences, the teacher asked four questions about the child’s sleeping habits at home:

Ending the account of the child’s sleeping habits in kindergarten, the teacher asks about the child’s sleeping at home. In line 1, she asks an open-ended question “How does he sleep at home?” which is immediately reformulated into a candidate question “does he sleep well at home?”. In designing candidate answers, speakers tend to propose legitimate actions (Pomerantz, 1988: 370), in this case, “sleeping well” instead of “sleeping badly”. According to Svennevig, the practice of reformulating questions with candidate answers is usual in conversations between native and non-native speakers, and immediate reformulations are designed to pave the way for (though not require) both minimal and extended answers (Svennevig & Cromdal, 2013: 200). The mother in this extract aligns to both options by confirming the candidate question (“yes”) as well as reporting problems about putting her child to bed (line 2). The account that the child has followed this sleeping pattern “all his life” has a certain excusing (Scott & Lyman, 1968) quality, possibly suggesting that the child’s sleeping habits are due to innate traits, rather than caused by parenting practices.

In line 3, the teacher asks another candidate a question following up on the subject: “does he fall asleep late at night?”. In response, the mother confirms (“yes”) and repeats the glossed account already given (“struggle even just getting him into bed”). In line 5, the teacher asks a question that narrows the subject “When does he fall asleep at night?”. Again, the mother aligns and provides an approximate time (“around ten o’clock”). In line 7, part of the teacher’s comment that the child does not appear to be tired at kindergarten is stressed (“don’t notice”). This report can be heard as a momentary mending and retreat from the investigator role, calming the mother (no need to worry, you’re doing fine). By speaking from the ECEC perspective, the teacher implicitly acknowledges bedtime as being the mother’s expert domain. Thus, a certain awareness of the public–private boundary being negotiated could be detected in this line. The rising intonation in the mother’s “No?” (line 8) may be heard as a cautious request for more information about the child in ECEC, but instead of elaborating, the teacher poses a new question about when the child gets up in the morning (line 9). Once more, the mother aligns and provides an exact time (“eight o’clock” in line 10) and, upon receiving this information, the teacher assesses that the child gets enough sleep (line 12).

As mentioned, the use of reformulations (line 1) can be a device for pre-empting potential problems in communication (Svennevig & Cromdal, 2013: 197). However, the move back from the candidate question (“fall asleep late at night”) in line 3 to asking about the exact time (“when”) in lines 5 and 9 suggests otherwise. Based on the teacher’s direct when question in line 5, it is more likely that in line 3 she pursued new (more exact) information about the child’s sleeping habits. This may suggest that speakers who adopt candidate answer designs do not always pursue a yes–no response, simply confirming their own model of the world.

The use of multiple questions and the explicit assessment of the child’s sleeping habits (line 12) give the sequence a certain investigative touch, examining in detail whether the child gets enough sleep, though a certain awareness of the delicacy of boundary work is displayed in line 7. In terms of privacy, the multiple questions made the mother accountable for providing family information about her child’s sleeping habits. Moreover, the assessment in line 14 represents an even deeper move into the parents’ private domain as the teacher in this turn topicalizes the parents’ need for “quality time in the evening”. The mother did not pick up on the quality time topic (not shown) and thus did not align with the teacher’s quite intimate style of communication (Burgoon, 1982: 221). At best, the instance demonstrates a more hybrid orientation to the public–private boundary on behalf of the teacher. Given the information in extract 4 (that the staff had not noticed the child being tired at kindergarten, line 7), it is hard to identify an obvious professional concern for the child’s well-being.

Discussion

To the family, bedtime (extract 4) is likely a more sensitive topic than language code at home (extract 1), as this may provide pointers to the intimate relationship between the parents (“quality time in the evening”) and lifestyle in general (the family’s preferences for sleeping, hiking, etc.). Rather than focusing on content, the paper has examined ECEC teachers’ interactional strategies for eliciting family information in parent–teacher conferences, and the parents’ responses to them. The analysis demonstrated a continuum of practices in terms of how and the extent to which parents were made accountable for providing family information in the conferences: Parents’ spontaneous comparisons (extract 1), fishing (extract 2) and asking questions (extract 3 and 4). In the example of parents’ spontaneous comparisons (extract 1), parental accountability was very low, as the teacher had not requested information about family affairs. The fishing device strategy (Pomerantz, 1980) represented a middle position, as this practice gave the parents a choice as to whether or not to provide the missing information. As could be expected, the teachers’ inquiries made the parents accountable for providing family information in a stronger sense, especially when the teacher asked multiple questions (extract 4).

What embedded understandings of privacy were thereby displayed in the eliciting practices? Undoubtedly, direct questions are more likely to challenge the family’s social integrity compared to more indirect strategies. In asking questions, the teacher positions herself as being entitled to know the matter in question, but the use of prefatory statements or accounts, explicating the teacher’s reasons for asking (extracts 3, 4), as well as mending actions (extract 4, line 7), can be seen as paying some attention to the issue of parents’ privacy.

An extensive example of boundary crossing was demonstrated in extract 4. In addition to the number of questions and the private content already commented on, the forms of inquiry adopted in the extract are also interesting. The shift from asking candidate questions (“Does he sleep well at home?”) to asking open when questions (the child’s bedtime and wake-up time) represented a shift from a less obliging question design to a more obliging question design. In CA research, open-ended question designs are considered to give speakers more freedom to formulate independent answers, compared to candidate questions where speakers are restricted to choose between ready alternatives or ready models of the world (see Svennevig & Cromdal, 2013: 201). However, this theorising presumes that professionals and clients have a shared project in obtaining accurate information about the client. If this premise does not hold (for instance, need for privacy), the shift to open-ended questions can be seen as dominating, rather than emancipating (see Foucault’s ideas of the “individualizing power” of contemporary pastor figures, where people are scrutinised by experts and experts teach them how to scrutinise themselves). While the less obliging candidate question design adopted in the first part of the extract allowed the mother to provide rather glossed information about the family’s sleeping habits, the following open-ended question did not.

Undoubtedly, the fishing strategy described in extract 2 represents a less intrusive action as the parents could choose whether or not to provide the missing information. When the fishing strategy is adopted, the implicit action is treated “as preferably not said” (Pomerantz, 1980: 198) and, in her paper, Pomerantz relates this phenomenon to the management of privacy:

We would argue that with respect to an orienting to privacy (“your business is your business”), this design lies somewhere in between absolutely respecting that right – for example, not considering asking, probing, or “fishing” (“if he wants to say, he will”) and orienting to sharing (“your business is my business”). (..) The “my side” tellings display an orientation to and acknowledgement of your right to privacy while not fully respecting it to the extent of no recourse (Pomerantz, 1980: 198).

Thus, on the one hand, the ECEC teacher does not disturb privacy by asking them directly why the child was not present in kindergarten. On the other hand, the fishing design also suggests telling as an optional action (which, in this case, was accepted by the parents, “we were at the eye specialist”). While exerting milder pressure, even the fishing strategy may be seen as having a control dimension. In this version, the teacher can be heard as orienting to “check” whether the parents had a legitimate reason for taking their child out of kindergarten on a particular day. Thus, exerting social control, or pursuing a concern, could be the implicit action “preferably not said” in this example. Other equally relevant candidates are asking out of sheer curiosity, small talk, snooping into other people's affairs, etc.

The parental practice of volunteering family information and providing the pursued information indicates that parents actively orient to the norm of visibility in child rearing (Alasuutari et al., 2014; Dencik, 1999), rather than accentuating the negotiation of privacy. However, although complying with the expectations in talk, there are also subtle signs of ambivalence (Merton & Barber, 1976) in terms of providing short or glossed answers (extracts 3 and 4) and accounts (Scott & Lyman, 1968) that defend/excuse practices in the home (extracts 1 and 4). This ambivalence may indicate that parents have privacy needs but that they lack the discursive resources to defend the private–public boundary in educational settings. It is possible that the discourse of the best interest of the child, which suggests that parents are accountable for how they present themselves and the home environment, provides poor conditions for the negotiation of privacy. Another interpretation could be that (some) parents orient to ECEC professionals as members of their primary group and that this kind of “kinning” may be functional in a post-traditional society. Thus, more qualitative research from the parents’ perspective is needed in order to get a more in-depth account of parents’ emotions and conceptions of privacy and boundary negotiations, for instance, examining whether there is a gap between the “desired” and the “achieved” level of privacy (Burgoon, 1982: 208) in ECEC settings.

Moreover, interactional studies involving more informants are needed to establish what constitutes normal and what constitutes deviant conduct in parent–teacher conferences. It is hard not to perceive the multiple inquiries in extract 4, mapping and assessing the child’s need for sleep, as a kind of policing (Donzelot, 1980). From an intersectional perspective, research should be conducted as to whether parents’ ethnic, sociocultural background, gender or age may impact the way that teachers negotiate privacy in educational settings. Given the size of this study, we cannot confirm this claim at this point. However, the phenomenon of asking minority parents multiple questions (extract 4) has been observed in another small ECEC study (Sand, 2014), and immigrant parents have reported a sense of being evaluated (Andenæs, 2011; Tembo & Studsrød, 2017: 114).

Conclusion

While it may seem trivial to study talk in parent–teacher conferences, interaction in everyday encounters may nevertheless reflect larger issues with a moral and even a political dimension. The OECD’s proposal to form a partnership with parents (“which implies a two-way process of knowledge and information flowing freely both ways”), which this study sheds light on, can ideally be portrayed in at least two ways: First, understanding ECEC staff and parents as an “integrated team” suggests that a high degree of sharing is taking place between the participants (“your business is my business”), and there is therefore little need to engage in public–private boundary work. In this scenario, staff and parents orient to each other in a hybrid and extended family fashion, and questions are normal and quite direct. (This was possibly the route taken by the ECEC teacher in extract 4, at least during some parts of the conference). However, the relationship between ECEC staff and parents can also be understood as a “complementary team,” in which parents and staff play different roles and have different expert domains (the parents for their child at home, the staff for the child in ECEC). In this scenario, which suggests that there is some distance between the parties, there is a certain need for the negotiation of public–private boundaries. Thus, to take care of the family's privacy needs, inquiries should be properly accounted for, or alternatively managed in more indirect ways.

In neither of the cases examined in this paper did the teachers’ eliciting actions appear to be necessary to take care of the child’s well-being, or at least the teacher did not explicate such reasons. Nevertheless, there were also signs of an awareness of the public–private negotiations: Questions were contextualised, fishing strategies were sometimes adopted, and two of the three teachers rarely asked for family information. While present ECEC practices (still) might be slightly closer to a “complementary” than an “integrated” understanding of the partnership between parents and staff, there are probably voices in the transnational political landscape who do not welcome a development into the latter in which childcare is a shared responsibility in a much stronger sense. Ultimately, the management of privacy in educational settings deals with a nexus of related ideological and political questions: What is the value of family? Who is responsible for bringing up children (what is left for the parents)? What is freedom? What is citizenship? What is the good life?, etc. These issues are intertwined with social class and cultural diversity, suggesting different ways of relating to educational institutions. Both Norwegian (Stefansen & Skogen, 2010) and US class research (Lareau, 2011) suggests that middle-class parents are more oriented to a close home-school cooperation than working-class parents. For the latter group, the family may still be more of a haven in a heartless world, meaning there is a greater need to keep ECECF staff at a distance (Stefansen & Skogen, 2010).

As referred to in the introduction of this paper, privacy is a human right, and it must be skilfully managed by ECEC staff. Thus, the competence and values of staff are of major importance in terms of realising “the real living law” (Lile, 2019: 148) in educational settings. The findings in this paper may have implications for (ECEC) teacher education which, not surprisingly, is primarily engaged with children’s rights and children’s citizenship (Brantefors et al., 2019). As previously mentioned, privacy presumes a segregation between the family’s “frontstage” and “backstage” (Goffman, 1959), which may be at odds with children’s rights (Østrem, 2008). From this perspective, the very issue of family privacy may appear out of place or old-fashioned, especially for younger people (Steijn & Vedder, 2015). In-depth education on human rights and ethics can help prepare teachers for the complexity of the field, where conflicting norms need to be identified and managed on a professional basis. Thus, practitioners and student teachers need knowledge about the law, the principle of integrity and its exceptions, both theoretically and practically in an every day/communication context.

Moreover, the findings in this study suggest that ECEC teachers’ knowledge of the social aspects of privacy needs to be strengthened. The hybrid border between the private and the public, and the (possibly unacknowledged) power of questioning described in this paper, indicate a need to develop professional standards about when to ask for family information (or not) and how this can be accomplished in everyday action. Working with authentic interaction data from the field (see for instance Stokoe, 2014) could be one route to enhance professional reflection in kindergarten and in ECEC teacher education.

References

Alasuutari, M. (2009). What is so funny about children? Laughter in parent–practitioner interaction. International Journal of Early Years Education, 17(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760902982315

Alasuutari, M., & Karila, K. (2010). Framing the picture of the child. Children & Society, 24(2), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00209.x

Alasuutari, M., & Markström, A.-M. (2011). The making of the ordinary child in preschool. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(5), 517–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.555919

Alasuutari, M., Markström, A.-M., & Vallberg-Roth, A.-C. (2014). The governance and the pedagogicalization of parents (pp. 99–111). Routledge.

Alf Petter, H., & Njål, H. (2010). Grunnlovsfesting av retten til privatliv? Jussens Venner, 45(2), 98–146.

Andenæs, A. (2011). Chains of care: Organising the everyday life of young children attending day care. Nordic Psychology, 63(2), 49–67.

Brantefors, L., Tellgren, B., & Thelander, N. (2019). Human rights education as democratic education the teaching traditions of children's human rights in Swedish early childhood education and school (Vol. 27, pp. 694).

Burgoon, J. K. (1982). Privacy and communication. Communication Yearbook, 6(1), 206–249.

Clayman, S., & Heritage, J. (2002a). The news interview: Journalists and public figures on the air. Cambridge University Press.

Clayman, S. E., & Heritage, J. (2002b). Questioning presidents: Journalistic deference and adversarialness in the press conferences of U.S. Presidents Eisenhower and Reagan. Journal of Communication, 52(4), 749–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02572.x

Dannesboe, K. I., Bach, D., Kjær, B., & Palludan, C. (2018). Parents of the welfare state: Pedagogues as parenting guides. Social Policy & Society, 17(3), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746417000562

Dencik, L. (1999). Små børns familieliv - som det formes i samspillet med den utdenomfamiliære børneomsorg. Et komparativt nordisk perspektiv. In L. Dencik & P. Schultz Jørgensen (Eds.), Børn og familie i det postmoderne samfund (pp. 245–272). Hans Reitzel.

Donzelot, J. (1980).The policing of families (G. Deleuze Ed.). London: Hutchinson & Co.

Drugli, M. B., & Undheim, A. M. (2011). Partnership between parents and caregivers of young children in full-time daycare. Child Care in Practice, 18(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2011.621887

Ellingsæter, A. L., & Leira, A. (2004). Velferdsstaten og familien: Utfordringer og dilemmaer. Gyldendal akademisk.

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

Foucault, M. (2007). Security, territory, population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–78. Palgrave Macmillan.

Framework Plan for Kindergartens. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Penguin.

Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Polity Press.

Heritage, J. (2002). The limits of questioning: Negative interrogatives and hostile question content. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(10–11), 1427–1446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00072-3

Heritage, J., & Clayman, S. (2010). News interview turn taking. In J. Heritage & S. Clayman (Eds.), Talk in action: Interactions, identities and institutions (pp. 213–226). Wiley-Blackwell.

Heritage, J., & Lindstrom, A. (1998). Motherhood, medicine, and morality: Scenes from a medical encounter. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 31(3–4), 397–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.1998.9683598

Hernes, H. (1987). Welfare state and woman power: Essays in state feminism. Norwegian University Press.

Karlsen, M. P., & Villadsen, K. (2007). Hvor skal talen komme fra? Dialogen som omsiggribende ledelsesteknologi. [Who Should Do the Talking? The Proliferation of Dialogue as Governmental Technology]. Dansk sociologi, 18(2), 7–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.22439/dansoc.v18i2.1901

Lareau, A. (2011). Concerted cultivation and the accomplishment of natural growth (2nd ed., p. 1). University of California Press.

Lasch, C. (1976). The family as a haven in a heartless world. Salmagundi (Saratoga Springs) 35, 42–55.

Leino-Kilpi, H., Välimäki, M., Dassen, T., Gasull, M., Lemonidou, C., Scott, A., & Arndt, M. (2001). Privacy: A review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 38(6), 663–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00111-5

Lerner, G. H. (2002). Turn-sharing. In C. E. Ford, B. A. Fox, & S. A. Thompson (Eds.), The language of turn and sequence (pp. 225–256). Oxford University Press.

Lile, H. S. (2019). The realisation of human rights education in Norway. Nordic Journal of Human Rights, 37(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/18918131.2019.1674007

Linell, P., Hofvendahl, J., & Lindholm, C. (2003). Multi-unit questions in institutional interactions: Sequential organizations and communicative functions. Text, 23(4), 539–571. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.2003.021

Markström, A.-M. (2005). Förskolan som normaliseringspraktik: En etnografisk studie. Ph.D. Linköping University,

Markström, A.-M. (2009). The parent–teacher conference in the Swedish preschool: A study of an ongoing process as a “pocket of local order”. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 10(2), 122–132.

Markström, A.-M. (2011). “Soft governance” i förskolans utvecklingssamtal. Educare, 2, 57–75.

Merton, R. K., & Barber, E. (1976). Sociological ambivalence. In R. K. Merton (Ed.), Sociological ambivalence and other essays (pp. 3–31). Free Press.

NESH. (2019, 08.06.2019). Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences, Humanities, Law and Theology. Retrieved from https://www.forskningsetikk.no/en/guidelines/social-sciences-humanities-law-and-theology/guidelines-for-research-ethics-in-the-social-sciences-humanities-law-and-theology/

Oltedal, S., & Nygren, L. (2019). Private and public families: Social workers’ views on children’s and parents’ position in Chile, England, Lithuania and Norway. FACSK, 14(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.31265/jcsw.v14i1.235

Organisation for Economic, C.-o. a., & Development. (2006). Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care.

Østrem, S. (2008). The public/private dichotomy: A threat to children’s fellow citizenship? International Journal of Early Childhood, 40(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03168361

Parrott, R., Burgoon, J. K., Burgoon, M., & LePoire, B. A. (1989). Privacy between physicians and patients: More than a matter of confidentiality. Social Science and Medicine, 29(12), 1381–1385. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(89)90239-6

Persson, S., & Broman, I. T. (2002). »Det är ju ett annat jobb»: Läraryrkets avgränsningar och lärarens socialpedagogiska ansvar. Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige, 7(4), 257–278.

Peräkylä, A. (2004). Realiability and validity based on naturally occuring interaction. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research. Sage.

Pomerantz, A. (1980). Telling my side: “Limited access” as a “fishing” device. Sociological Inquiry, 50(3–4), 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1980.tb00020.x

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 57–101). Cambridge University Press.

Pomerantz, A. (1988). Offering a candidate answer: An information seeking strategy. Communication Monographs, 55(4), 360–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758809376177

Sacks, H. (1987). On the preference for agreement and contiguity in sequences in conversation. In G. Button & J. R. E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organisation (Vol. 1, pp. 54–69). Multilingual Matters.

Sacks, H. (1995). Lectures on conversation. Vols I and II. Blackwell.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language (baltimore), 50(4), 696–735. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243

Sand, S. (2014). Foreldresamarbeid - vitenskapelige eller kulturelle praksiser? [Parent cooperation—Scientific or cultural practices?]. Barnehagefolk, 2, 44–49.

Schegloff, E. A. (2000). Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society, 29(1), 1–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500001019

Schegloff, E. A., & Sacks, H. (1973). Opening up closings. Semiotica, 7, 289–327.

Scott, M. B., & Lyman, S. M. (1968). Accounts. American Sociological Review, 33(1), 46–62.

Smette, I., & Rosten, M. G. (2019). Et iakttatt foreldreskap. Om å være foreldre og minoritet i Norge. NOVA.

Steensig, J., & Drew, P. (2008). Introduction: Questioning and affiliation/disaffiliation in interaction. Discourse Studies, 10(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445607085581

Stefansen, K., & Skogen, K. (2010). Selective identification, quiet distancing: Understaning the working-class response to the Nordic daycare model. The Sociological Review, 58(4), 587–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01941.x

Steijn, W. M. P., & Vedder, A. H. (2015). Privacy under construction: A developmental perspective on privacy perception. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 40(4), 615–637. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915571167

Stokoe, E. (2014). The conversation analytic role-play method (CARM): A method for training communication skills as an alternative to simulated role-play. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(3), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.925663

Svennevig, J., & Cromdal, J. (2013). Reformulation of questions with candidate answers. International Journal of Bilingualism, 17(2), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006912441419

Tembo, M. J., & Studsrød, I. (2017). Foreldreskap i en ny kontekst: Når mor og far har migrert til Norge. In I. Studsrød & S. Tuastad (Eds.), Barneomsorg på norsk : I samspill og spenning mellom hjem og stat (pp. 107–124). Universitetsforl.

ten Have, P. (2007). Doing conversation analysis: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Sage.

Thuen, H. (2008). Om barnet: Oppdragelse, opplæring og omsorg gjennom historien. Abstrakt forlag.

Tracy, K., & Robles, J. (2009). Questions, questioning, and institutional practices: An introduction. Discourse Studies, 11(2), 131–152.

Wang, J. (2006). Questions and the exercise of power. Discourse & Society, 17(4), 529–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926506063127

Wyness, M. (2014). Children, family and the state: Revisiting public and private realms. Sociology (oxford), 48(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038512467712

Acknowledgements

Partial financial support was received from Oslofjordfondet under Grant ES569234.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University Of South-Eastern Norway.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author reports there are no competing interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Solberg, J. Privacy in Early Childhood Education and Care: The Management of Family Information in Parent–Teacher Conferences. Hum Stud (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-023-09683-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-023-09683-5