Abstract

The aim of this paper is to determine whether and to what extent Woodward’s interventionist theory of causation is variable relative. In an influential review, Strevens has accused Woodward’s account of a damaging form of variable relativity, according to which obviously false causal claims can be made true by choosing a depleted variable set. Following McCain, I show that Strevens’ objection doesn’t succeed. However, Woodward also wants to avoid another kind of variable relativity, according to which it can be true that X is a cause of Y in one set of background conditions, but false in another. I show that Woodward’s account is problematically overpermissive, unless there are restrictions on the values that certain variables can take. I formulate a modified account that makes these restrictions explicit, then use it to argue that Woodward’s attempt to avoid relativity to background conditions is misguided. On the best interpretation of the interventionist theory, causal claims are assessed relative to a particular kind of variable set. Thus, I conclude that the theory should be understood as variable relative, in a specific, unproblematic sense.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Elsewhere, Woodward (2003, 7) describes his aim as ‘capturing or clarifying’ the “content” or “meaning” of various kinds of causal claim. Even when understood along these lines, however, his account is not intended to be metaphysical in nature.

The above definition makes use of the notion of an actual cause. This is best glossed as follows: X = x is an actual cause of Y = y if and only if (1) x and y are the actual values of the respective variables, and (2) there are other values of X and Y, x’ and y’, such that intervening to change the value of X from x’ to x would change the value of Y from y’ to y (Menzies 2009, 357–358).

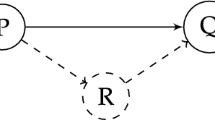

In Sect. 1.1, Woodward’s notion of an intervention was characterised as a three-place relation of the form: I is an intervention on X with respect to Y. For convenience, I sometimes refer to an ‘intervention on X’. This should still be understood as referring to a three-place relation—that is, to an intervention on X with respect to Y.

The notion of direct causation has to be relativised to a variable set, because it is always possible to insert an extra variable between a cause and its effect and thus ensure that there is no longer a direct causal connection between them.

Woodward does not state what it is for X to be correctly represented as a contributing cause of Y with respect to V. However, the most plausible interpretation, and the one I assume here, is the following: X is correctly represented as a contributing cause of Y with respect to V if and only if it is true that there is some intervention on X that would make a difference to the value of Y when all the variables in V except for X, Y, and any variables on a causal chain linking X and Y are held fixed at some value. To accept a stronger interpretation of ‘correctly represented’ would be to say that X is correctly represented as a contributing cause of Y with respect to V if and if X actually is a cause of Y, which would be viciously circular.

Although, of course, anyone can choke on a peanut.

Assume that V* also contains a set of background variables that are held fixed at the values they normally take in the actual world. For more on this, see Sect. 4.

More technically, Strevens points out that Woodward’s strategy (i.e., giving an account of relativised contributing causation and then derelativising by existentially quantifying) only works if relativised contributing causation is monotonic. That is, if it is not possible for X to be a contributing cause of Y relative to V, but not relative to \(\mathbf V ^{+}\), where \(\mathbf V ^{+}\) is a superset of V (2008, 174–175). Strevens argues that Woodward’s account of relativised contributing causation is not monotonic (2008, 175–176). However, McCain shows that it is.

Thanks to Woodward for bringing this distinction to my attention.

The reader may be concerned that what it is for a variable taking some value to be a realistic possibility is unclear. I return to this concern at the end of Sect. 5.

There are circumstances in which we set the background variables at non-actual values: this is what makes it possible to think about causation in counterfactual scenarios. In these situations, we replace the actual values of variables with those in the relevant counterfactual scenario.

It is also open to Woodward to say that when we make causal judgements about human physiology, we are making judgements about actual human physiology, given our current state of knowledge. In other words, to relativise causal claims to our state of knowledge. However, since relativising causal claims to a particular set V* is more precise than relativising them to our knowledge at the time of utterance, it still seems preferable to accept that whether X is a cause of Y is relative to a set V*. Thanks to an anonymous referee for raising this point.

According to contrastive accounts of causation, causation is a multi-place relation between causes, effects, and contrasts. On the most popular, four-place version, causal claims have the form: x rather than x* causes y rather than y*, where x* and y* are contrasts. See Schaffer (2005), Schaffer (2013), Maslen (2004) and Hitchcock (1996).

Assume that the people in both groups otherwise have a healthy diet.

References

Hitchcock, C. (1996). Farewell to binary causation. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 26, 267–282.

Hitchcock, C. (2007). Prevention, preemption, and the principle of sufficient reason. Philosophical Review, 116, 495–532.

Lewis, D. (1979). Counterfactual dependence and time’s arrow. Noûs, 4, 455–476.

Maslen, C. (2004). Causes, contrasts, and the nontransitivity of causation. In J. Collins, N. Hall, & L. A. Paul (Eds.), Causation and counterfactuals (pp. 341–358). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Maudlin, T. (2004). Causation, counterfactuals, and the third factor. In J. Collins, N. Hall, & L. A. Paul (Eds.), Causation and counterfactuals (pp. 419–443). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McCain, K. (2015). Interventionism defended. Logos and Episteme, 6, 61–73.

Menzies, P. (2004). Difference-making in context. In J. Collins, N. Hall, & L. A. Paul (Eds.), Causation and counterfactuals (pp. 139–180). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Menzies, P. (2007). Causation in context. In H. Price & R. Corry (Eds.), Causation, physics, and the constitution of reality (pp. 191–223). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Menzies, P. (2009). Platitudes and counterexamples. In H. Beebee, C. Hitchcock, & P. Menzies (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of causation (pp. 341–367). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pearl, J. (2000). Causality: Models, reasoning, and inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2005). Contrastive causation. Philosophical Review, 114, 297–328.

Schaffer, J. (2013). Causal contextualism. In M. Blaauw (Ed.), Contrastivism in philosophy (pp. 35–63). New York: Routledge.

Spirtes, P., Glymour, C., & Scheines, R. (2000). Causation, prediction, and search. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Strevens, M. (2007). Review of Woodward, Making things happen. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 74, 233–249.

Strevens, M. (2008). Comments on Woodward, Making things happen. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 77, 171–192.

Woodward, J. (2003). Making things happen: A theory of causal explanation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woodward, J. (2008). Response to Strevens. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 77, 193–212.

Woodward, J. (2010). Causation in biology: Stability, specificity, and the choice of levels of explanation. Biology and Philosophy, 25, 287–318.

Woodward, J. (2015). Methodology, ontology, and interventionism. Synthese, 192, 3577–3599.

Woodward, J. (2016). The problem of variable choice. Synthese, 193, 1047–1072.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Arif Ahmed, Jim Woodward, Huw Price, Hasok Chang, Claire Benn, Alison Fernandes, Shyane Siriwardena, Adam Bales, Sharon Berry, Olla Solomyak, and an anonymous referee for providing valuable feedback on various drafts of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Statham, G. Woodward and variable relativity. Philos Stud 175, 885–902 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-017-0897-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-017-0897-2