Abstract

Following the global financial crisis, banks have become more regulated to advance ethical sales cultures throughout the sector. Based on case studies of three retail banks, we find that they construct the ‘appropriate advisor’ in different ways. Inspired by Bakhtin’s work on ethics, we propose a vocabulary of relational ethics centered on the ‘answerable self.’ We argue that this vocabulary is apt for studying and discussing how organizations advance ethical sales cultures in ways that instead of encouraging value congruence and alignment allow for ethical openness. In such cultures, employees—as moral agents—are morally questioning, critically self-reflexive, and answerable for their own actions toward others in their social relationships. Our paper makes three theoretical contributions, namely, problematizing the idea of cultural alignment and value congruence, demonstrating that identity regulation can both comprise and support the ‘answerable self,’ and advancing our understanding of the interdependence of ethical openness and ethical closure in fostering ethical sales cultures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The financial sector faced several ethical challenges after the 2008 global financial crisis, including repeated scandals related to fraud, selling illegal products, money laundering, and the Panama Papers.Footnote 1 Such scandals tarnished the image of the whole sector and damaged stakeholder trust in financial institutions (Mueller et al., 2015). Before the global financial crisis, the culture of banks was marked by an aggressive sales orientation using ‘cowboy’ techniques to push unsustainable products to customers, even vulnerable ones (Forseth et al., 2015; Hill, 2011). Such a culture was supported by bonus systems, peer rivalry, and prestige related mainly to sales. These sales cultures contributed to the stigmatized image of bankers as more dishonest than prisoners (Cohn et al., 2014) and driven by greed and self-interest (Hill, 2011). However, a paradigm shift has occurred in recent years (Lenz & Neckel, 2019), where the financial sector and employees working in banks can no longer exclusively focus on profitability and shareholders, but must also consider their moral obligation to broader society and the multitude of stakeholders. Some have even argued that moral orientation is an inherent part of economic action: ‘Moral struggles and the different path they inspire are not a distraction from some “real” economic issue beneath. They stand at the economy’s core and at the heart’ (Fourcade et al., 2013, p. 636, cited in Lenz & Neckel, 2019, p. 131). Such a paradigm shift has increased the external regulation of banks as well as self-regulation through codes of conduct (Lenz & Neckel, 2019).

However, despite the increased regulation of the financial sector in the wake of this paradigm shift, we still lack insights into how banks strive to ensure and strengthen ethical sales cultures. For example, the chairperson of the UK Financial Services Authority stated:

Bank executives face the challenge of setting clearly from the top a culture which tells people that there are things they shouldn’t do, even if it is legal, even if it is profitable and even if it is highly likely that the supervisor will never spot them. (cited in Cohn et al., 2014, p. 86)

A report from the Cass (now Bayes) Business School (Gond et al., 2014), however, pointed out that despite increased regulation, ethical cultures in banking remain to be developed. Similarly, other studies have shown that bankers have ‘teflonic identities’ (Alvesson & Robertson, 2016) and that mis-selling remains an established practice (Brannan, 2017). Furthermore, Ferreira et al. (2016) find that the potential for unethical behavior and abuse of power may be even greater than before owing to increased digitalization and decreased face-to-face interactions. However, new sales rhetoric and ‘right selling’ practices are emerging in Scandinavia, which focus on improving the customer experience and raising customer satisfaction (Forseth et al., 2015). This paper adds to this emerging discussion about ethical sales cultures in contemporary banking.

The existing literature on ethical cultures focuses on value congruence, where cultural management initiatives are designed to ensure that employees’ ethical values align with those of the organization and that clear rules about their duties, roles, and responsibilities are formulated (Ambrose et al., 2008; Paine, 1994; Palazzo & Rethel, 2008). The aim is to grow non-ambiguous ethical cultures marked by ‘ethical closure,’ meaning that only one specific view of what is ‘ethically appropriate’ is accepted as the ‘way things are.’ In this study, we propose the notion of the ‘answerable self’ to understand the design of ethical sales cultures in a way that goes beyond value congruence. Despite longstanding criticisms of cultural engineering (Kunda, 1992; Müller, 2017) and attempts to institutionalize ethics (Costas & Kärreman, 2013; Kärreman & Alvesson, 2010), we find that the prevailing ideal of non-ambiguous ethical cultures still exists. The purpose of our paper is to problematize this ideal of value congruence and alignment and propose—based on empirical findings—other ways in which ethical sales cultures are and can be fostered. As such, we add to emerging discussions of a more relational and responsive grounding of ethics in contemporary organizations (Anton, 2001; Kopf et al., 2010; Loacker & Muhr, 2009; Murray, 2000).

Theoretically, we draw upon the work of Mikhail Bakhtin, whose ethical philosophy provides a useful vocabulary to study the dynamic relationships among culture, identity construction, and ethics and discuss the ethical foundation of the judgments, choices, decisions, and actions of the ‘answerable self.’ Following Bakhtin, we conceive the ‘answerable self’ as morally questioning, critically self-reflexive, and answerable for its own actions toward the other party in social relationships. The idea of the ‘answerable self’ challenges the normative ideals of cultural alignment and value congruence as the best way to achieve ethical sales cultures and instead opens up a debate of how cultural management may allow space for employees’ ‘answerable selves.’ We advance our understanding of ethical cultural management as occurring through the opening and closing dynamics of ethical discourse. Rather than reviewing the business ethics literature (e.g., O’Fallon & Butterfield, 2005; Rhodes, 2022), we situate Bakhtin’s ideas of the ‘answerable self’ and relational ethics vis-à-vis two other ethical positions often at play when engineering cultures, namely, formal and content ethics (Kopf et al., 2010).

Empirically, we examine how the ‘appropriate advisor’ is discursively constructed by the management and financial advisors in three retail banks. Our empirical material consists of case studies of these three banks based on interviews with managers and frontline personnel. In our analysis of the empirical material, we examine different approaches to managing the sales culture and how the ‘appropriate employee’ is discursively constructed as a form of identity regulation. Using both our Bakhtinian framework and our empirical analysis, we identify three main ethical positions from which ethical sales cultures are fostered, namely, formal ethics, content ethics, and relational ethics. On this basis, the paper makes three theoretical contributions: problematizing the ideal of cultural alignment and value congruence, demonstrating that identity regulation can both comprise and support the ‘answerable self,’ and advancing our understanding of the interdependence of ethical openness and ethical closure in fostering ethical sales cultures.

Theoretical Framework

Ethical Sales Cultures

Research on ethics in organizations tends to take two approaches (Ambrose et al., 2008), namely, focusing on moral development and decision-making at either the individual level (Kohlberg, 1981) or the organizational level to examine how organizational attributes such as the culture, ethical climate, reward systems, policies, values, and influence affect employees’ morality at work (Ambrose et al., 2008; Brannan, 2017; Palazzo & Rethel, 2008). In the financial sector, individual-level research has focused on bankers’ moral character and virtuousness (Cohn et al., 2014; Rocchi & Thunder, 2019). Research on ethical climates and cultures, however, argues that employees’ ethical behavior cannot be understood independently of the organizational context in which they work (Paine, 1994). Brannan (2017), for example, illustrates that mis-selling in a financial services firm is promoted by both the introductory training provided by the organization and its sales rituals that celebrate sales at all costs. McCabe (2009) illustrates that the values of customer service promoted by management are difficult for employees to align with a sales rhetoric that sees everyone as a potential sales target. Similarly, Palazzo and Rethel (2008) argue that unethical behavior in the financial sector may arise not only in organizations in which such behavior is promoted but also in organizations in which conflicting ethics are not managed clearly. Thus, organizational members may be ‘tempted’ to exploit loopholes or ambiguities.

The literature thus suggests the importance of ethical value congruence between organizational and individual values as well as shared understandings among organizational members devoid of ethical ambivalence and ambiguities. As such, it proposes that organizations should aim for non-ambiguous cultures; clear rules to deal with conflicting duties, norms, and loyalties; and clearly defined roles and responsibilities (Palazzo & Rethel, 2008). Furthermore, employees’ values should be aligned with organizational values for the former to comply with the ethical rules of the company (Ambrose et al., 2008; Paine, 1994). Ambrose et al. (2008), for example, argue that ‘employees need to understand and agree to the underlying values presented in these codes and politics: developing ethical value congruence is essential for successful implications of these procedures’ (p. 331). While such conclusions may seem intuitively right, we question whether the development of ethical employees as ‘cultural dupes’ only following the values of the organizational culture without an ethical sensitivity of their own is apt in the financial sector. In particular, we critically consider whether the inherently ambiguous nature of the work of frontline bank employees and often competing definitions of ‘what is right,’ which vary depending on the rules and regulations, organizational cultures, customers’ perspectives, and employees’ moral compass, make ethical decisions and behaviors based on value congruence possible or even desirable.

Engineering Culture, Identity Regulation, and the Ethically Appropriate Employee

Numerous critical management studies have demonstrated that ‘culture’ can be engineered and designed using normative control (Kunda, 1992; Müller, 2017). Designing culture ‘from above’ implies management’s identity regulation of employees in a discursive construction of the ‘appropriate individual.’ Fleming and Spicer (2003) argue that ‘an engineered culture attempts to manufacture positive sentiments (beyond consent) and reconcile workers to antagonistic employment relationships through creating particular types of personhood’ (p. 158). Thus, cultural management can be seen as a form of identity regulation through which management aims to control employees’ values, hopes, aspirations, and identity to control their actions without the need for direct supervision (Alvesson & Willmott, 2002; Costas & Kärreman, 2013; Kunda, 1992). Identity regulation is defined as a discursive accomplishment that implies ‘the self-positioning of employees within managerially inspired discourses about work and organization with which they may become more or less identified and committed’ (Alvesson & Willmott, 2002, p. 602).

Such identity regulation occurs through the management of meaning in which discursive and symbolic resources and practices are used to promote a particular ‘appropriate employee’ beneficial to the organization (Kärreman & Rylander, 2008; Kunda, 1992). The ‘appropriate employee’ not only acts but also feels, values, and aspires in ways aligned with the organization. Management may accomplish such cultural alignment through promotional practices, leadership, the division of labor, and organizational hierarchies (Alvesson & Willmott, 2002), crafting hopes and expectations through career management and human resources practices (Alvesson & Robertson, 2006; Costas & Kärreman, 2013), using internal branding practices (Brannan et al., 2015; Frandsen, 2015), and linking lifestyle choices and privately held ideas of ‘fun’ and ‘family’ to the organization (Endrissat et al., 2017; Fleming & Sturdy, 2009; Land & Taylor, 2010). Alvesson and Kärreman (2007a) argue that ‘individuals are produced, rather than discovered, in HRM processes’ (p. 712), which they describe as ‘social architectures’ (p. 713).

Critical studies of normative control and identity regulation in relation to establishing ethical and socially responsible cultures highlight firms’ attempts to institutionalize ethics (Costas & Kärreman, 2013; Fleming & Sturdy, 2009; Kärreman & Alvesson, 2010) and examine identity regulation as a managerial way of producing an ‘ethically appropriate individual’ (Costas & Kärreman, 2013). The concept of ethical closure is inspired by Deetz’s (1992) concept of discursive closure, which happens ‘when discussion is thwarted, a particular view of reality is maintained at the expense of equally plausible ones, usually to someone’s advantage’ (p. 189). An important mechanism in ethical closure is ethical sealing, where a particular set of moral judgments and issues is highlighted as the only important set of ethical issues to consider. Ethical closure can be seen as a way in which ‘ethical considerations are arrested, blocked, and short-circuited’ (Kärreman & Alvesson, 2010, p. 58). These studies illustrate that ‘discourses and practices promote the construction of an idealized socially, ethically and ecologically responsible corporate self along with clear pathways of enacting it’ (Costas & Kärreman, 2013, p. 395), often using social architectures such as global standards, protocols, codes of conduct, and corporate social responsibility programs and projects as well as participating in philanthropic activities outside work and promoting the organization’s ethical values. A certain view of what is ethically appropriate is accepted as the way things are, leaving out alternative meanings or experiences. Ethical closure, in other words, ‘eliminates the space for moral debate’ (Costas & Kärreman, 2013, p. 409).

To extend the literature on the production of the ‘ethically appropriate individual’ in an organizational setting, Bakhtin’s theoretical framework for studying the dynamic relationships among culture, identity construction, and ethics is highly relevant. While organizational studies typically center on Bakhtin’s ideas of the ‘dialogical self’ and ‘carnivalian self’ (Emerson, 1995), we draw attention to his early concept of the ‘answerable self.’ Bakhtin (1990; 1999) argues that too little attention has been placed on the ‘answerable self’ when situating ethics in universal laws (form) or cultural norms (content). The individual is understood as sensible, responsible, and answerable toward others. The ethics of answerability arise in the concrete dialogue between self and other against the cultural background. Bakhtin thus problematizes the assumptions of value congruence and organizational culture marked by ethical closure, while highlighting the importance of understanding the ‘answerable self’ as emerging in social interactions with others.

Bakhtin and His Critique of Formal and Content Ethics

Bakhtin can be categorized not only as a literary theorist but also as an ethical thinker (Emerson, 1995). In his two early writings of ‘Art and Answerability’ (1990) and ‘Toward a Philosophy of the Act’ (1999), he was interested in moral philosophy and occupied with the dynamic relationships among ethics, culture, and life. He was critical of understanding ethics as only located in universal moral laws and rules (form) and/or in cultural norms and virtues (content). Instead, he favored a relational form of ethics that arises in social interactions between the ‘answerable self’ and ‘the other.’ Bakhtin’s relational ethics are thus connected to similar understandings of ethics such as responsible intersubjective relationships (Pollard, 2011), dialogical ethics (Kopf et al., 2010), communicative encounters (Murray, 2000), responsible subjects (Loacker & Muhr, 2009), and ethics in everyday life and practice (Anton, 2001).

The problem, Bakhtin argues, with the formal form of ethics inspired by Kant’s categorical imperative is that it ‘determines the performed act as a universally valid law, but as a law that is devoid of a particular, positive content’ (1999, p. 25). Ethics demand that ‘the performed act must be conformable to the law’ (Bakhtin, 1999, p. 25). In such formal ethics, the focus is placed on a self whose moral conscience is defined by moral law (Brown, 1995; Kopf et al., 2010). The individual internalizes the universal, rational law to the extent that their will and ability to morally self-reflect ‘dies’ (Bakhtin, 1999, p. 26). Similarly, ethics located in specific values and norms of definite content (Anton, 2011; Kopf et al., 2010), which apply to everyone and every situation, are problematic, as they are imposed on the individual agent from the outside (Kopf et al., 2010). Indeed, ‘a performed act is ethical only when it is governed throughout by an appropriate moral norm that has a definite universal content’ (Bakhtin, 1999, p. 22). Such content ethics thus consist of instituted rules, norms, and values that are assumed to apply to all humans. Families and communities, religion, and culture can teach people to be morally appropriate. The moral system and its precepts on morality are accepted by the moral agent and internalized into their conscience (Brown, 1995). The internalization of the moral system implies that the individual is compelled to conform to the values and norms of the moral system: ‘any falling off from this standard, then, represents failures of achievement’ (Brown, 1995, p. 282).

Although formal and content ethics take different ethical positions, they share an external grounding of morality, a somewhat generalized conception of conscience and act imposed on and internalized by the individual (Bakhtin, 1999; Brown, 1995). Conceived of as monological ethical discourses (Brown, 1995), their mechanism works in the same way as the monological approach to culture: they close down dialogue and finish off the individual: ‘monologic solutions are grounded in something that is external to the individual but which the individual comes to internalize to the extent that the inner dialogic process of moral debate ceases’ (Brown, 1995, p. 296). Rather than being attentive to moral questioning and ‘doubts over the appropriate standard itself’ (Brown, 1995, p. 283), monological ethical discourses lead to ethical closure based on ‘the monologic principle of moral certainty’ (Brown, 1995, p. 285).

The ‘Answerable Self’

Against the prevailing notions of formal and content ethics, Bakhtin searches for an ethic that stems not from external sources, but from within the social interaction between the ‘answerable self’ in dialogue with ‘the other.’ He sees ethics as inseparably entangled with the relationship with others, compelling the individual to be answerable to those others (Bakhtin, 1999). Answerability concerns being accountable for one’s actions toward others. The inner dialogue with one’s moral self constitutes the discursive site of moral conscience to which the ‘I’ always needs to return to nurture and preserve a genuine ‘”I” of my own’ (Emerson, 1995, p. 412). A genuine ‘I of my own’ is not to be understood as an essential, self-contained ‘I’ that lives only for oneself or one’s own sake (Bakhtin, 1999) but as a dialogical, relational, and responsible ‘self’ who asks the ethical and reflexive question: ‘did I do it and do I accept responsibility for it, or do I behave as if someone else, or nobody in particular, did it?’ (Morson & Emerson, 1990, p. 70). Reflexivity means questioning and critically thinking about the kind of person I am and the kind of person I want to be, which—from a dialogical perspective—is a relational activity undertaken by the self inquiring into their relationships with others and the surrounding world (Cunliffe, 2016). To act ethically calls upon the relational and reflexive capacity to be morally sensitive and responsive toward others in all situations of everyday life: ‘To do so requires that I actively “enter in” to the other’s position at every moment, a gesture which is then followed not by identification (in Bakhtin’s world, fusion or duplication is always sterile) but by a return to my own position, the sole place from which I can understand my “obligation” in its relationship to another’ (Emerson, 1995, p. 412). Much in line with Bakhtin, Cunliffe argues that we need to open ‘up our own practices and assumptions for working toward more critical, responsive, and ethical action’ (2016, p. 415). This we can do by adopting and developing a ‘critically reflexive questioning of past actions and of future possibilities’ (2004, p. 408) as an existential way of being providing the bases for self-conscious and ethical action.

The ‘answerable self’ does not give oneself away to obey the instituted rules and laws, values, and norms without caution. Rather than relying on instituted moral sources of values, the ‘answerable self’ cautiously relates to them during social interactions and relationships (Anton, 2001). We must be answerable to others for our performed actions without pretending or hiding behind cultural norms or calls from authorities or universal laws. There is no such alibi in being (Bakhtin, 1999). This relational approach to ethics engages the moral agent in an open-ended, ongoing, and social process of ‘moral questioning’ (Brown, 1995). In contrast to ethical closure relational ethics are open and uncertain, as ‘moral agents struggle to learn that moral arguments cannot be absolutely settled’ (Brown, 1995, p. 278). Social moral agents ‘are forced to rely on their own ethical resources’ (Brown, 1995, p. 296), consisting of their unique values, consciousness, and ethical standards (Anton, 2001; Murray, 2000), which arise and are socially constructed in response to ‘the other’ in social interactions. Ethics are ‘not an individual or monological phenomenon but instead a sort of conversation between self and other as dialogical-ethical participants in the interhuman encounter’ (Murray, 2000, p. 134).

Following Bakhtin’s conception, ethics are understood as a ‘conversation between one’s own-most answerability and the calls to responsibility of others’Footnote 2 (Murray, 2000, p. 133). As a unique ethical participant, the agent is obliged to participate in the dialogue by asking questions, being responsive, and investing their entire self in the discourse (Bakhtin, 1984). The ethics of the ‘answerable self’ rely on a mutual self–other relationship, as the self and other co-participate in their mutual development against the cultural background. The individual is understood as sensible, responsible, and answerable toward others. The ‘I’ takes an active, critical, and ethical stance toward the centripetal content of the monological design of culture and the way in which the culturally dominant discourse reasons for and gives meaning to the act.

The Centripetal/Centrifugal Forces and the ‘Answerable Self’

Given the vast attention of organizational studies paid to the value congruence between organization and individual and the engineering of ethical culture, we question—based on Bakhtin’s early idea of the ‘answerable self’—the extent to which cultural management in the financial sector has fostered organizational cultures that allow or even nurture the existence of ‘answerable selves’ among organizational members. We join other studies that have drawn primarily on Bakhtin’s later notion of dialogism to point out that identity regulation rarely stands uncontested. While the managers (and other dominant groups) within the organization may attempt to impose monological and unitary constructions on employees’ identities, employees also have the power to oppose and construct their own identities (Humphreys & Brown, 2002; Rhodes, 2002). As such, we can understand the engineering of culture and identity regulation as a centripetal force within the organization that seeks to achieve congruence between organizational and individual values to define what is ‘right’ and ‘good.’ Humphreys and Brown’s (2002) study, however, highlights the need to consider the centrifugal powers in which employees construct their own meanings based on their experiences and ability to be self-reflexive in the rich and messy domain of life. A centripetal force ‘serves to unify and centralize the verbal and ideological discourse of language, norms, thoughts and ideas’ (Bakhtin, 1981, cited in Svane, 2019, p. 8), while the opposing centrifugal force moves outward to a multiplicity of ‘voices,’ thereby creating a ‘space for the plurality of unmerged voices and consciousness’ (Svane, 2019, p. 9). Bakhtin’s understanding of the world as ‘becoming’ in a constant struggle between its closing (centripetal) and opening (centrifugal) forces challenges the idea of ethical closure and value congruence as ways to produce more ethical cultures in organizations. The ‘answerable self’ indeed operates in a ‘messy and heterogeneous’ world of life.

The centripetal and centrifugal forces are closely related to Bakhtin’s (1999) distinction between the world of culture and the world of life, with the latter constituting the source of the centrifugal forces. Culture conceived of as that which is collective and shared and which hence implies consistency, consensus, and alignment is thus closely related to these centripetal forces and a monological consciousness. Through socialization, conformity to the world of culture is imposed upon us, constraining our lives and demanding us to live and act in accordance with the established cultural values, norms, rules, and official discourses. Differing from this cultural objectification of acts and lives, the world of life is the only world in which we create, cognize, contemplate, live, and die. We are responding to the events within our lives. The centrifugal forces of the world of life are thus sensitive to diversity, heterogeneity, and alterations, as they respond to and create new meanings of unrepeatable, once-occurring events of messy daily life. The ethical act plays a central role in bridging the world of culture and the world of life. The nature of the act differs between the two worlds. In the world of culture, it is represented and objectified, abstracted, and generalized. The concrete act that is actualized and accomplished, however, occurs in the world of life as a singularly occurring event. Thus, the act represents an ontological hallmark of Bakhtin’s philosophy: ‘to be in life, to be actually, is to act, is to be unindifferent toward the one-occurrent whole’ (Bakhtin, 1999, p. 42).

Such centripetal and centrifugal forces are vital to consider when examining cultural management in the financial sector, as they allow us to see the extent to which the engineering of the ‘ethically appropriate self’ is based on the centripetal forces of conforming to rules and norms or the centrifugal forces that make room for an ‘answerable self’ to emerge. Are employees allowed or even expected to pose questions in situations of moral uncertainly (to critically reflect on their social relationships and interactions with customers)? This is especially important considering that frontline employees such as financial advisors work in a life domain characterized by multiple social interactions with customers, to whom they are expected to be both responsive and responsible. In the following, we present our methodological considerations, before returning to these questions.

Methods

Generating the Empirical Material

In this study, we are driven by our curiosity to understand how banks have tried to advance ethical sales cultures since the global financial crisis in 2008, which provoked considerable uncertainty in the banking sector and caused banks to critically reconsider their business ethics. We are therefore interested in studying how banks have attempted to move on after the financial crisis by taking actions to improve their ethical sales cultures and appropriate advisory behavior. To study this phenomenon, we gathered and analyzed empirical material on sales cultures through interviews with the management and employees at three Scandinavian retail banks: BankNordic, BestBank, and OneFinance. These banks were selected based on theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007) in that they were chosen ‘for the likelihood that they will offer insights’ and ‘because they are unusually revelatory, extreme exemplars, or opportunities for usual research access’ (ibid, p. 27). First, BestBank and BankNordic are two large Scandinavian Banks. Due to their size, the sector usually takes heed of the procedures and changes in these two banks. Based upon their representation in the public media, we were under the impression that BestBank had undergone a comprehensive sales cultural change, whereas BankNordic, which holds the image of a more traditional, conservative bank, had not. These impressions raised our curiosity about how these two banks may have responded differently to developing an ethical sales culture. As we became interested in examining their ethical sales cultures based on Bakhtin’s framework, we began to look for a third case to provide insights into a more relational ethical position on sales cultures. We read in the media about a smaller bank, OneFinance, that had seemingly adopted a different approach to cultural management and approached it about participating in our explorative study as a comparative case to the two others.

We applied a context-dependent narrative case study inspired by Dyer and Wilkins (1991) and Flyvbjerg (2006). The objective of this type of case study method is to get close to real life as it unfolds in its concrete context. In that sense, the case study method provides concrete, practical, and context-dependent knowledge on value in and of itself (Flyvbjerg, 2006). Furthermore, we used an abductive approach based on Alvesson and Kärreman (2007b) research methodology for ‘theory development through encounters between theoretical assumptions and empirical impressions that involve breakdowns’ (p. 1266). In developing theory, we were driven by what was unanticipated and unexpected as well as that which puzzled us. While collecting our data, we were surprised that despite all three banks being under similar national and sector-wide regulation and despite our assumption that we would find all three forms of ethics (formal, content, and relational) present in each bank, the three banks approached their ethical sales cultures in three distinct ways that indeed corresponded to each of these three ethical positions. The fusion between the empirical material and Bakhtin’s theoretical conceptualization gave rise to the idea of considering these three approaches to creating ethical sales cultures as three ideal types.

Our case selection thus moved toward what Eisenhardt and Graebner (2007) call polar cases and Flyvbjerg (2006) paradigmatic cases, which hold ‘metaphorical and prototypical value’ (Flyvbjerg, 2006, p. 232). A paradigmatic case may be difficult to identify: ‘No standard exists for the paradigmatic case because it sets the standard’ (Flyvbjerg, 2006, p. 232). The paradigmatic potentiality of the case therefore tends to rely on intuition and may even be impossible to determine fully in advance (Flyvbjerg, 2006). In our study, we expected all three cases to illustrate an effort toward fostering an ethical sales culture. We also expected some context-dependent differences across the three banks. Nonetheless, it came as a surprise during the analysis that the three cases were more prone to the three ideals or prototypes of the three ethical positions.

To understand how these three banks attempted to construct an ethical sales culture, we conducted interviews with 10 financial advisors and two management representatives in each. Hence, we conducted 36 interviews in total, each lasting approximately 90 min. The interviews took place in 12 branches across the three banks, often in the meeting rooms in which customer meetings are usually held. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim and all the names, including those of the participating banks, were changed to protect their anonymity. In addition, a research diary was kept in which reflections on the interviews, meetings, and observations at the different branch visits were noted. The interviews with the financial advisors were often conducted after a preliminary meeting with the management representatives to explain the company’s strategy and its background as well as how they perceived the role of the financial advisors in this strategy.

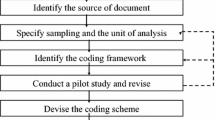

Analyzing the Empirical Material

As our analytical procedure, we conducted a within-case analysis, which included case study write-ups for each site. We focused our analysis on how management had planned to grow an ethical sales culture in relation to how frontline employees sold financial services and provided financial advice. In each of the three cases, the strategies included elaborate considerations of customer experiences, placing financial advisors’ relationships with customers at center stage. We analyzed the interviews with the management representatives to understand how they discursively constructed the ‘appropriate financial advisor’ and their strategies for designing an ethical sales culture. Then, we focused on the financial advisor interviews. We identified the way they constructed themselves, their work, and what constituted ‘good advice’ and ‘selling’ in their discourses. We became particularly interested in how financial advisors were positioned and positioned themselves in the interviews. We were inspired by discourse analysis that focuses on positionings, which enabled an analysis of the duality of identity and discourse, as identity is viewed as being both produced by and a producer of discourse (Davies & Harré, 1990). Discourses produce certain positions that individuals can accept, reject, or modify (Holmer-Nadesan, 1996). Davies and Harré (1990) state that when a person accepts a position, this means that they see ‘the world from the vantage point of that position and in terms of the particular images, metaphors, storylines, and concepts which are made relevant within the particular discursive practice in which they are positioned’ (p. 46). This analysis illustrated how the ‘appropriate financial advisor’ was discursively constructed, signifying the types of ethical practices, behaviors, and attitudes that management and employees saw as important for being a successful advisor.

We then searched for cross-case patterns and found that management was, in different ways, preoccupied with managing and changing the sales culture among frontline employees in all three cases. We identified the key practices and dominant discourses in the three banks related to the construction of the ‘appropriate financial advisor.’ Although both management and employees drew on similar broad ideas of what constituted the ‘appropriate advisor,’ the cultural management and managerial perspective on how to achieve the strategic objectives differed, as discussed in the findings section. Hence, we began to focus on the prevalence of (a) structures and processes, (b) values and education, and (c) individuals’ discretion during customer interactions. We saw that the cases each carried elements of all three ethical positions (formal, content, and relational ethics), yet varied in how prevalent they featured in the bank. We thus started an iterative process oscillating between the empirical material and the Bakhtinian framework of the ethical positions to explain both the theoretical ideas and the empirical practices of these ideas, working towards the creating Table 1. We started by focusing on the ethical governing principle, ethical resources, the locus of ethics, ethical sources, the identity approach, and ethical closure/openness of each of the three positions and then further illustrated these by using examples of the practices of these positions witnessed in the empirical cases. Next, we finalized our narrative descriptions of each case (Eisenhardt, 1989), focusing specifically on verbatim descriptions from our empirical material to bring the ethical positions and cases to life. Finally, although we searched for counter-stories in our data (Müller & Frandsen, 2021), we found little rejection or resistance among employees toward the managerially defined culture.

Critical Reflections on the Interplay Between the Theory and Empirical Material

The case studies were first approached as a narrative inquiry (Dyer & Wilkins, 1991) driven by an interest in exploring management and employees’ experiences with and interpretations of their organizational sales culture. Despite this empirical starting point, we acknowledge the role of the researcher’s preunderstanding, which is already informed by certain perspectives, theoretical frameworks, vocabularies, and interpretive repertoires, yet guiding and providing direction in the process of constructing the empirical material. We therefore agree with Alvesson and Kärreman (2007b) that the empirical material is inextricably fused with theory, theoretical ideas, and conceptual language and that it therefore can be conceived of as ‘an artifact of interpretations and the use of specific vocabularies’ (p. 1265).

The fusion between the theory and empirical material—even in the early phase of constructing the empirical material—makes it important to critically reflect upon their roles in theory development. Empirical material can be used to illustrate, challenge, and rethink theory, thereby constituting ‘a resource for developing theoretical ideas through the active mobilization and problematization of existing frameworks’ (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007b, p. 1265), whereas theories ‘are instruments that provide illumination, insight, and understanding’ (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007b, p. 1267), rather than mirroring reality (Eisenhardt, 1989).

In our study, the empirical material was used to illustrate the theoretical idea of having found three potentially and metaphorically paradigmatic approaches to constructing ethical sales cultures, while Bakhtin’s theoretical distinction between the three ethical positions operated as a way of further conceptualizing and idealizing these approaches (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007b; Freese, 1980). Bakhtin’s conceptual framework helped us make our findings more theoretically abstract and, in this sense, more general. Subsequently, in the last part of the writing process, we moved toward conceptual closure to magnify, clarify, and conceptualize the dominant differences and characteristics across the three approaches, as exemplified in Table 1. Generalizing using conceptual abstractions of the empirical material provides better stories and narrative cases rather than better statistical generalizability (Dyer & Wilkins, 1991; Flyvbjerg, 2006). Such narrative case studies thus offer clues for reflexive thinking as well as for context-dependent judgment regarding use among researchers and practitioners (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007b; Flyvbjerg, 2006).

Findings

BankNordic

BankNordic, a major Scandinavian bank, defines its ideal financial advisor through the formulation of the ‘BankNordic Way,’ a method of building and maintaining customer relationships. It focuses on written procedures to prepare, execute, and document meetings. The customer meeting is predefined using a fixed agenda, taking the customer (and advisor) through different generic ‘phases’ from uncovering the customer’s interests and needs to providing solutions and reaching agreements. The documentation of the meeting is emphasized as crucial; thus, this generic process for the meeting must be followed to ensure that the advisor (and customer) has all the relevant information and that the former can document that the right solution for the customer has been suggested. The ‘BankNordic Way’ thus aims to (a) meet customer needs, (b) ensure consistent customer service across branches and advisors, (c) ensure an efficient customer meeting, and (d) ensure that all rules and regulations are met. The ideal financial advisor follows these internal predefined processes and procedures to achieve ‘world-class service,’ which is the bank’s mantra.

The managerial discourse constructing the ‘appropriate advisor’ focuses on the techniques and methodologies that should direct every customer meeting.

You can say that really in my world, and maybe it’s not politically (correct) in a bank if you say so, but I do not see any difference between advice and sales, but for me, it’s the same methodology. (…) You can use the same technique and methodology, so it’s a way, a methodology to discover the customer’s needs, and to understand the customer a bit deeper and in that way deliver a solution. Then others might object ‘but then you sell something,’ then I say; ‘but I deliver a solution to something that the customer wants.’ There are actually two basic methods, but what I want to say is that basically, it’s the same structure, only different words you use. So, our advice methodology assumes, I would really say an outer wheel,Footnote 3 (…) and for us, it’s about structure in your own everyday, how do you work? Do you structure your calendar? To create the opportunity to be proactive and be successful at the meeting itself, it is all about how to book customers, how to follow up on the meeting, etc. But what we often explicitly talk about, when we speak of advisory methods, is the inner wheel: When do we meet the customer? When the customer is in the chair in front of me, how do you handle the customer? This is what I call the inner wheel of our methodology, and it is often what we call our advisory methodology. (Tony, Branch Director and Regional Director, Responsible for Sales and Marketing)

The management representative above underlines that only by following the methodology and techniques defined by management is it possible to both meet the customer’s demand for service and the bank’s demand for profit.

The structures, procedures, and methodologies are furthermore discursive, constructed as important for achieving a consistent customer experience regardless of with whom customers interact.

It is important to the bank that we meet the customer the right way, in a reasonably similar experience, whether you meet me or meet someone else. If you go to the office in X city, in Y city, or Z city then it should be about the same, that’s BankNordic, that’s our brand, so it’s of overall importance. (Tony)

The discourse of the financial advisors illustrates that discussions about ‘good customer advice’ and ‘being a good financial advisor’ are often linked to the quantification of meetings, customer satisfaction ratings, and so on by the financial advisors:

We will have 10 [meetings] a week. (…) Everyone has the same target. Then, we have a target of how much we should achieve [in the meetings]. It’s not... we cannot just have 10 meetings and not achieve anything. We might have a certain volume of savings and other things, but what we are measured on, the most important thing really, is customer satisfaction, so we must have x number of 10/10 clients. Therefore, you want to get a 10 on customer satisfaction. After such a meeting, a survey is sent, a customer satisfaction measurement, to the customer to fill in how they experienced the meeting. And we will have a certain number of these a year, and that’s really the most important goal for you. (Eva)

The ‘BankNordic Way’ methodology for customer meetings was frequently referred to in the interviews, although the participants often argued that the fixed agenda and predefined structure of the meetings are difficult to maintain in ‘real life,’ where timeframes are constrained and the purpose of the meetings varies. Advisors should typically provide good customer service in a way that ensures a ‘top score’ in their customer satisfaction surveys, which are sent out after every meeting.

Documentation about financial advice played a significant role in the interviews.

When I’ve met a customer, even if nothing happens, I have to fill in everything and write a protocol about the customer advice. What and why I have done this, everything must be included when writing the protocol. So it’s fully controlled. (Hanna)

So all the advice that has to do with placing money is going to be documented and it will be even more now. It’s really been very bad. (...) But more and more demands are coming from the Financial Supervisory Authority today. Also from the bank, so it’s very focused on documentation. (Heidi)

Documentation and following the rules and procedures are linked to ‘good advice’ not only because of managerial demands but also because employees perceive it as a way of protecting themselves from accusations of ‘bad advice,’ as in the following account:

It is about selling or advising the right product and justifying why. And I think that’s very important, because if the customer has not understood it and you meet the customer again, then the customer is not satisfied. And we are not really allowed to sell today. When I write in my advisory protocol, I must have checked, ‘Does this make sense for the customer’s finances?’ ‘Is this something that the person should do at all?’ ‘What does the income look like and what are the expenses?’ and ‘What do the financial possibilities look like?’ It is always a balance. (...) Well ... once we received a customer complaint. (…) So it is so important to write what the customer has asked for, and why he has done what he has done (…) it’s so important to do good foundational work at the beginning and get to know the customer. (Hanna)

The focus on rules, procedures, and methodologies means that advisors have limited freedom and responsibility to make decisions. They often have to consult the credit department or their managers before making agreements with customers:

I have worked at Bank A. In the transition, I thought it was a bit more top-rated here, that’s a bit more bureaucratic and a bit more rigid. At Bank A, you had a bigger mandate to make decisions on mortgages and other stuff. Here, one must go to a committee and go through it all. So that was a difference. (Peter)

To summarize the BankNordic case study, we observe that by focusing on rules, regulations, and imperatives as well as documentation, measurements, and ratings, it uses imperative and technical devices to regulate, standardize, and control the ‘appropriate advisor’ and ‘appropriate advice.’ BankNordic adheres primarily to an ethical position of formal ethics, valuing compliance with the organizational rules and alignment in the pursuit of the organizational goals. The advisory activities and work are structured, organized, and methodologically approached using the outer and inner wheels as regulating devices. These devices aim to bring forward the identity of the ‘appropriate advisor,’ who delivers consistent customer service, acts compliantly in the right way, and conducts efficient customer meetings. Adhering to the rules and maintaining the standards constitute the predominant ethical grounds on which the ‘appropriate advice’ is supplied. Grounded on these external moral imperatives, the centripetal force of formal ethics leads to a moral certainty and ethical closure rather than stimulating the inner moral debating and questioning undertaken by a moral answerable agent.

BestBank

BestBank is a large bank that spans several countries in Scandinavia. At BestBank, management has initiated a large cultural change program to transform financial advisors’ moral compass from short-term, profit-oriented selling as the key factor to success within the bank to a more long-term, relational understanding of service. Thus, the focus is placed on emphasizing customers’ needs, wants, and dreams rather than the (short-term) profit of the bank. The head of personal banking explains the former culture as follows:

Our mindset must be that we do everything we can, so no customer leaves the bank dissatisfied. This mindset must permeate the way we work. (Tom, Head of Personal Banking, Internal Communication)

Let us be honest. We have been very focused on sales and that our customers bought our products. This is not unusual, and it is not illegal, but at some point, it becomes too much with all this focus on achieving product-related objectives. I would much rather talk about what is required for our customers to perceive us as friendly, accommodating, competent, and truly interested in helping. (Tom)

The cultural change program positions the ideal advisor differently. Advisors are now required to ensure that ‘no customer leaves the bank dissatisfied,’ and as such must ‘put themselves in the customer’s shoes’ and view the service from the customer’s perspective. Bank advisors are answerable to customers rather than the bank under the assumption that this approach will be profitable for the bank in the longer run.

To change the values, mindset, and behavior of financial advisors, numerous initiatives have been undertaken. These have included the abandonment of all sales-related reward systems, which have been replaced with customer satisfaction surveys providing instant feedback from customers on the quality of their meetings. To help an advisor recognize the shift toward understanding customers’ needs, wants, and dreams, management organized seminars; therefore, all financial advisors spent a considerable amount of time on e-learning and in discussions in their local branches. Typically, e-learning and discussions would analyze a customer complaint and the situation leading up to the event, before addressing how such complaints could be prevented in the future and how financial advisors could work more diligently to improve customer service. Customers were grouped according to their preferred communication method. New practices for calling customers were established and all advisors were expected to have talked to around 600 households in the last year. While advisors had previously contacted customers in relation to sales campaigns, they now called customers to maintain frequent interactions and uncover potential business to increase customer satisfaction. New practices for meeting preparations were also introduced via e-learning, and advisors were given more responsibility but also more freedom to make decisions on, for example, credit issues. Management often talked about local empowerment and set up feedback workshops at which advisors were asked to give and receive feedback to/from colleagues to improve the customer experience. New values or ‘cornerstones’ were communicated frequently in internal communication, both from the Head of Personal Banking and from their immediate managers.

After management initiated these changes, financial advisors were allowed and indeed expected to help everyone regardless of the level of engagement with the bank. Before these changes, customers had been categorized, with ‘standard’ customers not offered financial advisors but instead liaising with the bank via the call center. As is evident in the excerpt below, financial advisors now took up the new narratives and positioned customers as to be pleased in every possible way.

Now we look more from the outside in. (...) ‘I’m imagining myself in your chair—as a customer.’ What I usually explain to my customers is, ‘I’m sitting in your place as a customer and looking at what you need. What can benefit you? What is in it for you?’ In contrast to earlier, where we thought: what’s in it for me? (Poul)

The financial advisors appear to embrace the new understanding of their role as creating satisfied long-term customers rather than focusing on short-term, profit-oriented sales.

It is customer satisfaction that is the headline of everything we do, i.e., no bad cases (...) No customers leave BestBank dissatisfied. This is what pops up in my mind flashing. And everyone can relate to this one way or the other. (…) No one could leave BestBank dissatisfied, period. (Anna)

It’s very personal. What can I do to make this my way, so it’s very much about the behavior we have and the way we think. (...) Put myself into the customer’s place and understand their needs as a customer—and really come up with some good suggestions that can help the customer in getting a better image of BestBank—and something that the customer actually needs. (Clara)

The financial advisors highlight episodes in which they succeeded in providing advice for customers that served the latter’s best interest rather than the bank’s.

So, I think this is the greatest thing when I can make a difference. That I can match the others’ [competitors’] solutions and do something a bit more cool, that’s also nice, I think it is really fantastic when I can make a difference purely by providing the right advice. (Thomas)

Many of the financial advisors highlight that the e-learning education and training sessions they received provided them with new inspiration on how to carry out their jobs. This, they feel, had implications for how they consider their role and interact with their customers. Importantly, the advisors see this as simply the need ‘to do the right thing’ from the perspective of customers, which they find rewarding.

But today, the education has provided me with a new type of question, it has provided me with a development fostered by knowing how to ask the right questions. Also, the learning/development for me as a person. (...) When I’m sitting here and thinking about it, I guess it is because I sometimes take the freedom [to find the right solution.] (...) Such a meeting, the customer, when she came out, she almost had tears in her eyes, and her little brother, because I do not know how much of what she understood, he was just as overwhelmed when they left. They had simply succeeded in achieving what they wanted. Such things, I like! Going years back then, I can assure you, we had done everything we could to get our money back. We would not have seen it from the customers’ perspective. We only saw it from the bank’s perspective. (Sofia)

To summarize, BestBank differs from BankNordic by being more oriented toward content ethics and instituted values and norms than toward the universal rules and standards of formal ethics. Rather than emphasizing sales targets, BestBank has changed to focus on customer satisfaction and the customer experience and views the advisor as key to building long-term customer relations. The ‘appropriate advisor’ can understand the customer’s perspective; acquaint themselves with the customer’s situation; judge the appropriate and right advice themselves; and communicate with the customer in a friendly, helpful, accommodating, and competent way. In this sense, BestBank has begun to emphasize relational understanding and a moral space for the ‘answerable self’ to some extent. BestBank’s centripetal approach to developing the ‘appropriate advisor’ is pivotal for understanding its move toward content ethics. It aims to change the mindset and behavior of advisors through competence development, training, and cultural programs that internalize its ethical cultural values and norms. The content ethics of BestBank thus consist of a shared value-bearing moral system that aims to align the mindset and behavior of advisors as well as define and fix the cultural content of the ‘appropriate advisor.’

OneFinance

OneFinance is significantly smaller and more locally oriented than the two other banks. Its culture is influenced by a long tradition of value-based management and self-management in which financial advisors solely concentrate on their customers and often see themselves as running their own ‘small bank’ within the bank. The Deputy Director of OneFinance explains that the former CEO defined good banking as follows:

It is the bank that treats the customers in a proper fashion and the bank that is best at making its employees happy. (…) these values lived for many years and it manifested itself by the way he [the former CEO] actually kicked out our business procedures and the control department. He said, we will close down all of that and start an era where we trust each other. (…) I have trust in my employees that they are considerate, then there is no need for those damn rules, as long as we share the same values. (…) This is when the value-based management show started and it ended up in self-management because he thought that when you are a value-based company then you also work in another way than the traditional rule-based and hierarchically structured organization. It is about freedom to take responsibility. (Kenneth, Deputy Director)

The Deputy Director also explains that financial advisors are not rewarded for sales, there are no sales budgets, and they do not follow up on sales, as OneFinance does not want to incentivize employees to pursue self-interest:

Morals and ethics are insanely important in personal relationships and morals and ethics are precisely that you do not recommend products because it benefits the bank and also acknowledges if you make mistakes. Be considerate human beings. We are bank people. We are also bank people when we are off work, so you need to behave in a proper manner. (Kenneth, Deputy Director)

As such, the Deputy Director assumes that financial advisors are personally responsible and answerable for their own acts. Indeed, financial advisors’ discursive constructions of ‘good advice’ center on building honesty, trust, confidence, and credibility in the advisor–customer relationship:

It has to do with trust and a sense of being safe. If you cheat people, just once in relation to price, terms, credibility, or ..., then you have really lost the entire game. So it is about being honest and proper in living up to what promises you give to the customers (…) you must be honest and you must be trustworthy. I have no problem giving a rejection. I have no problem giving a commitment, but what you’re aiming for are your honesty and your fairness. (…) Do not withdraw from your commitment or come up with sad excuses or a half-apology. If we have made a mistake or something has happened, we face it. This is the right thing to do in the long run. So, we may miss the mark once in a while, when we are wrong about something, but we should also be able to acknowledge that. (…) Just once they find out that what I have said is not true, then I have a bad case. I can’t live with that. (…) we can make mistakes, it’s quite fair, and then we acknowledge that and we are honest about it, we don’t cover it up. (Jens)

As an example of an earlier incident, some financial advisors in the bank had recommended investment solutions that ultimately caused customers to incur substantial losses. However, the bank covered all customers’ losses and withdrew the product immediately, apologizing publicly that it had made a mistake. Other banks selling the same or similar products did not cover their customers’ losses.

That’s why people seem to think, okay, OneFinance, it’s cool and fair. Because we do not have such ‘a spot on the shirt’ that we just try and wipe off on our customers. That’s also my own ethics. I should not wipe anything off on the customers. (…) it has to do with credibility and trust, and those things are our most important parameters in the bank. (Monika)

Facing mistakes instead of covering them up and being honest, credible, and transparent are continuously evoked as central to being a good financial advisor. Here, credible and transparent means to …

Comply with agreements, and behave properly. If we say ‘yes’ to a customer, then we say ‘yes’ – and we do not change our minds after a while. We stand by our words and our actions, and we do what we say we will do. (…) I say why I am saying ‘no.’ I also say why I say ‘yes.’ It gives customers a sense [of security]. (Jonas)

Being close to customers, in relation to both knowing and understanding their lives, as well as physical proximity in the form of sharing hugs and meeting face-to-face is highlighted as an important part of the bank’s culture rather than numbers and statistics:

We can easily draw a lot of numbers and statistics, but why concentrate too much on that initially? Instead, [I] take the time to consult the customer, talk to them about what they want, what is important to them. Quickly you know what type of customer they are, and what they are interested in. (Eva)

I still believe in meeting people. I still believe that you can make video conferences and all that, but you sense each other in a different way when you meet, I think that will never go out of fashion. (Karen)

This is not highlighted by the two other banks, where the customers are more geographically dispersed and often interact with advisors over the phone, via email, and through net meetings.

In summary, OneFinance promotes an ethical position that is much closer to Bakhtin’s ideal conception of the relational ethics of answerability than that of the other two banks. Dialogue, conversations, and time spent with customers are pivotal to OneFinance, along with trust in advisors, as reflected in allowing them space for autonomy and self-management. The advisor is trusted to behave responsibly and honestly; to judge, decide, and act wisely; and to stand by their words and actions—even if mistaken or at fault. The appropriate identity of the advisor is the considerate human being; this reference to human being is discursively significant, as it accentuates the ethical consideration of business and sales. Similarly, the discursive references to my own ethics and freedom to take responsibility indicate a culture that affords an open space for a morally debating and questioning ‘answerable self.’ By conducting my own ethics and standing by my words and actions, the ‘appropriate advisor’ emerges as a social moral self, who assumes responsibility for their performed acts instead of hiding behind the authority of management systems or cultural traditions. Rather than relying on externally derived values for guidance, the ‘answerable self’ is critical and cautiously relates to the rules and norms in the context. Ready to correct and compensate for errors of judgment, the ‘appropriate advisor’ is also ethically answerable to the customer with respect to both the content of their advice and the resulting outcome. Hence, OneFinance management aims to create an open and free space in which ethical, reflexive, and sensitive relational selves appear.

Three Ethical Positions for Fostering Ethical Sales Cultures

Using Bakhtin’s framework to understand the three cases, we can see that each of the cases attempts to foster ethical sales cultures from the three dominant ethical positions: formal ethics in BankNordic, content ethics in BestBank, and relational ethics in OneFinance. These ethical positions are shown in Table 1.

We have demonstrated that the sales culture in BankNordic is engineered predominantly from a position of formal ethics, implying extensive formalization by clearly laid out rules, standardized procedures, and documentation requirements. The bank has developed a structured and formalized methodology for financial advisors to carry out their everyday work and hold meetings with customers, and their ‘success’ is measured based on customers’ ratings. As such, the identity is approached in a formal and impersonal way and the ethical grounding of appropriate behaviors is based upon sources external to the individual. The ‘appropriate advisor’ complies with these rules and procedures and the goal is to ensure consistent customer service and efficiency in customer interactions. A profit orientation seems to be prevalent and there are no clear boundaries between service and sales. The fostering of ethical cultures from a position of formal ethics means that moral consciences become defined by following the moral law, rules, and imperatives, leaving little room for critical reflexivity or moral questioning to emerge in social interactions with customers. In that sense, ethical closure and moral certainty are achieved through the centripetal forces of rules and regulations closing down ethical questioning. The case study thus shows little evidence of the ‘answerable self’ in play; rather, employees are concerned about ‘covering their backs’ to avoid being held accountable for any mistakes.

In BestBank, the sales culture seems to be pursued primarily from the position of content ethics, as management is preoccupied with designing new norms and values that construct the ‘appropriate advisor’ at this particular organization as friendly, accommodating, competent, and helpful. The bank has initiated a cultural change program, which is moving away from goals and measurements of product sales to an orientation on customer satisfaction. The new cultural change program is also moving attention away from categorizing and ranking customers based on value to encouraging employees to treat all customers equally regardless of their level of customer engagement. Corporate values and cornerstones are formulated to institute new norms, which are shared with employees through such activities as seminars, e-learning, discussions in local branches, workshops, and feedback from co-workers. New practices for contacting and communicating with customers have replaced the former sales campaigns, and thus follow-up calls are made based on the advisor’s judgment rather than dictated by sales campaigns. The ‘appropriate advisor’ is thus one that is less profit-driven and sales-oriented but rather focused on doing the ‘right thing’ from a customer perspective. They embrace a long-term, big-picture approach to profitability and customer relationships. The moral conscience of the ‘appropriate employee’ is defined by following normative values, and thus ethical grounding is still based upon sources outside the individual, yet internalized through education, training, and corporate discourses, thereby producing organizational subjectivity. Accordingly, the centripetal forces of cultural corporate discourse also seek to produce moral certainty and ethical closure.

While BestBank designs its ethical sales culture from a content ethical position, aimed at employees internalizing a shared moral compass through education and training, the new norms and values are created in a way that enables employees to emerge as ‘answerable selves’ in their customer interactions to some degree, especially using the mantra of ‘putting yourself in the customer’s shoes’ and helping customers in any way necessary. The long-term perspective and relaxed focus on short-term profit and sales provide wiggle room for the ‘answerable self’ to navigate customer relationships; however, significant cultural management ensures that the ‘answerable self’ still performs within the culturally prescribed rules of appropriate behavior.

Finally, OneFinance manages its ethical sales culture from a relational ethical position in which there is ample room for personal and reflexively driven ethics encouraging employees to be answerable to customers. The value-based culture is designed around self-management, autonomy, and ambassadorship. The ‘appropriate employee’ is designed based on the unique individual being responsible and honest as well as able to judge, decide, and act wisely in relation to customers. The ethical grounding is thus to a much larger extent based upon the critical reflexive and self-conscious source of the inside of the individual. In this sense, it seems as if OneFinance—to a greater extent than BestBank—is aiming to create a dialogical space for critical reflexive questioning. This self-managed culture allows employees to co-construct their unique identities by drawing on a wide range of identity resources and discourses; they are not just ‘passive dupes’ of the managerial discourse, which seems to be more the case at BankNordic. Rather, employees are given the freedom to take responsibility, correct and compensate for mistakes, and make wise judgments in their customer relationships. As such, the moral conscience is defined in dialogical relationships with ‘others.’ The idea of being a ‘considerate human being’ relying on ‘my own ethics’ is strong in OneFinance and its employees talk frequently about honesty, transparency, reflexivity, and responsiveness (e.g., stressing the need to stand by their words when dealing with customers). In contrast to BestBank and BankNordic, by inviting the multiple voices of advisors and customers to participate in a dialogue, OneFinance seems to be growing a culture that is centrifugally open toward critical reflexive questioning and answerability and subsequently to moral uncertainty and ethical openness.

Our analysis shows that—at the extreme position—the monological ethical discourse in BankNordic can lead to ethical closure, as ‘the right thing to do’ is carefully regulated through rules, structures, and processes in a way that closes any moral debate. In this sense, formal ethics and, to some extent, content ethics accentuate a split between the abstract, designed culture and the concrete world of life of financial advisors. Their messy world of life is characterized by manifold, diverse customer interactions that can hold an infinite number of moral dilemmas, which the culture seeks to reduce through simplistic rules, procedures, norms, and values. We contend that this challenges the construction of an ethical sales culture and the ‘appropriate employee,’ as such a split can enhance the passive and unethical human existence of hiding or pretending rather than being answerable.

Discussion

This paper examines how ethical sales cultures are built in the financial sector. In particular, we focus on how the ‘appropriate employee’ is discursively constructed by the management and financial advisors in three banks. To understand this, we offer the Bakhtinian idea of the ‘answerable self’ and relational ethics as ways to challenge the prevalent ethical positions—in both form and content—that can be used to manage culture and engineer the ‘appropriate employee.’ The ‘answerable self’ is defined as a dialogical, relational, and responsible ‘self’ who asks ethical and self-reflexive questions in their social interactions and relationships with others. Case studies of three Scandinavian banks are used to demonstrate that the positions of formal ethics, content ethics, and relational ethics arise in different ways to construct an ethical sales culture.

Our study makes three theoretical contributions: a) problematizing the ideal of cultural alignment as the solution to ethical sales cultures, as suggested by the literature; b) adding to the idea of identity regulation by highlighting answerability and relational ethics as compromised by identity regulation; and c) advancing our understanding of ethical cultural change as occurring through the opening and closing dynamics of ethical positions. In the following, we discuss each of these three contributions in detail.

Problematizing the Idea of Cultural Alignment

Ethical sales cultures are often constructed through legislative regulation based on laws and rules observed by the entire financial sector. This type of regulation inscribes itself into the sphere of public policymaking as a way of regulating human behavior (Cserne, 2013). In addition, several banks have attempted cultural change and provided training on moral values (Velasque, 1992) to foster a certain type of ethical and responsible employee. Despite all three banks in our study facing the same national and international regulations, they held different dominant ethical positions in the design of their sales cultures: formal, content, and relational ethics.

The literature on ethical value congruence shows that aligning organizational and individual values is imperative and thus that organizations should foster clear cultures to ensure that employees understand, agree, and ‘live’ their ethical values (Ambrose et al., 2008; Paine, 1994; Palazzo & Rethel, 2008). This implies clear rules, codes, and policies about what constitutes the ‘appropriate employee’ and how to enact this. In our paper, however, we take a different perspective and problematize whether the ideal of cultural alignment is achievable or even desirable. Based on Bakhtin, we argue that the possible downside of such cultural alignment is that the notion of answerability and relational ethics (i.e., being honest, responsible, and considerate in interactions with others) is suppressed or compromised by the identity regulation put in place by engineered sales cultures. In the three cases, we show that each foregrounds an ethical position that values formal, content, or relational ethics, while pushing the other ethical positions into the background. This means varying degrees of space for an ‘answerable self’ to emerge. Formal ethics and content ethics work in the cases of BankNordic and BestBank through centripetal forces that aim for ethical closure around externally grounded ethical values. Only relational ethics, as exemplified by OneFinance, allow room for ethical openness that grounds ethics from inside the individual.

We might conclude that more banks should simply follow OneFinance’s example. However, an exclusive focus on one dominant ethics might be risky—even an exclusive focus on relational ethics. Such an approach may be taken advantage of by less honest individuals and thus we argue that elements of all three ethical positions are needed to build ethical sales cultures. Our point is that banks and other organizations should not seek to construct ethical sales cultures based on only one of these governing principles, namely, legislative regulation, cultural regulation, or relational answerability. Nor is it advisable to see a centripetal alignment of all three. Rather, we advise that banks seek an approach that leaves space open for all three to co-exist to sustain sound moral questioning and debating, even though the co-existence of the three dimensions could entail ethical struggles and tensions in the concomitant opening and closing of ethical discourse through both centripetal and centrifugal forces.

Interestingly, there was little opposition by employees to the centripetal cultural forces to which they were subjected. In particular, BestBank employees were highly committed to the new norms and values of being friendly, helpful, and competent, as this approach was seen as less restrictive than its previous short-term, profit-oriented sales culture. Future research could study the management of ethical sales cultures in banks in which all three ethical positions are at play, and perhaps in tension within each other, and create what Bakhtin calls ‘heteroglossia’—an intertwinement of ethical discourses. The mutual relationships among the three ethical positions could also be investigated more closely in future research.

Identity Regulation and Answerability

While most of the literature on cultural change has focused on formal ethics and content ethics as governing principles (Ambrose et al., 2008; Brannan, 2017; Kärreman & Alvesson, 2010; Costas & Kärreman, 2013; Palazzo & Rethel, 2008), we propose a Bakhtinian perspective to highlight the need for relational ethics of ‘answerable selves.’ Following Bakhtin, ethical identities are described as ‘each person’s moral life quest is to continually “author” a self that is in a changing dynamic ethical relationship with all of the other people encountered in social relationships and cultural groupings’ (Edmiston, 2010, p. 198).

In our cases, we examine management’s engineering of culture to regulate the character, role, subjectivity, and behavior of advisors. This identity regulation does not center on the individual, but on a preferred objectified archetype designed through the social architecture (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007a). In BankNordic, performing cultural management from a formal ethical position allows little room for employees’ ‘answerable selves.’ However, OneFinance’s cultural management opens up a space for employees’ ‘answerable selves’ to be at work. We thus see the ethical openness and ‘answerable self’ as a conscious effort created by the organization.

Bakhtin sees the ‘answerable self’ as a bridge between culture and the messy domain of life. To synthesize or bridge the two domains, he highlights the role of the ‘answerable self’ (Emerson, 1995) at the expense of formal and content ethics that mainly operate in the domain of culture. In contrast to formal ethics and content ethics, answerability is submerged into and develops organically from within the messy world of life, where we respond to endless possibilities, surprises, puzzling situations, and confusions. To judge, choose, and act wisely in the world of life calls for relational ethics and the relational capacity of being morally sensible, sensitive, and responsive toward others in all moments, situations, and events of everyday life.

Although cultural management using formal and content ethics risks compromising relational ethics, OneFinance has successfully engineered an open culture encouraging the answerable ethics of critical self-reflexivity and responsiveness to flourish in customer interactions. Management provides an ethical openness in which employees’ ‘answerable selves’ are encouraged. This is an open culture in which the centripetal forces of the culture also allow for the centrifugal forces of life in the continuous dynamics of ethical closure and ethical openness. In the ethical sales culture of OneFinance, employees are expected to take a critical and self-reflexive stance. They should not hide or pretend, but rather appear answerable to customers.