Abstract

This manuscript offers a qualitative exploration aimed at proposing effective strategies for enhancing compliance with and enforcement of labor laws in Bangladesh by diminishing the incentives for non-compliance. The study relies on primary data obtained from statutes, legal decisions, and secondary data sourced from scholarly articles, books, and book chapters, among others. Employing a cost-benefit analysis approach from the employers’ perspective, the study contends that showcasing the superior costs associated with violating labor laws, in comparison to the benefits gained, will incentivize employers to prioritize compliance to safeguard their interests. To this end, the research puts forth eight distinct techniques or mechanisms to curtail the benefits derived from disregarding labor laws. These strategies are thoughtfully organized into two categories, namely “increasing the likelihood of self-enforcement” and “supporting by other actors.” The proposed techniques for enhancing compliance with and enforcement of labor laws in Bangladesh hold significant potential in benefiting key stakeholders, policymakers, and practitioners in the field. Furthermore, the study’s findings carry valuable implications for other developing countries in the South Asian region, given their similar socio-economic and cultural contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A recent study emphasizes that compliance is not only a mere approach but also a necessary regulatory obligation (Beerbaum, 2021). In the realm of industrial relations, which involves companies, workers, and trade unions, compliance with labor law serves as a fundamental regulatory instrument (Grgurev, 2021). To ensure adherence to these laws, various enforcement methods are employed (Del Punta, 2021). These enforcement methods represent legal techniques designed to compel stakeholders to comply with the laws to a certain extent (Syed, 2020a). However, in the context of labor law, many employers perceive it as burdensome and costly, potentially hindering their management practices and cutting into their profits. Consequently, employers often attempt to circumvent these enforcement techniques and seek ways to evade compliance (Davidov, 2021). Additionally, there are practical challenges associated with enforcing labor laws that must not be overlooked in this discourse. Notably, labor laws are generally considered a combination of both private and public law (Bogg, Costello, Davies, & Adams-Prassl, 2015). Private law, specifically in the form of employment contracts, serves as the foundational framework wherein individuals are expected to assert their rights. Simultaneously, due to the seriousness of certain violations, labor law transgressions are treated as criminal offenses, necessitating state enforcement methods. In theory, these two enforcement mechanisms, enabling workers to sue employers and allowing states to prosecute offenders, should counteract the propensity for violating labor laws. However, in practice, neither of these approaches proves entirely effective, rendering the enforcement of labor laws inherently challenging (Davidov, 2021).

In the context of employment contracts, self-enforcement is often deemed impractical due to several reasons. Firstly, the process involved in self-enforcement is lengthy and cumbersome, dissuading many employees from pursuing this avenue (Haque, Sarker, Rahman, Rahman, & Rakibuddin, 2020). Additionally, a significant number of employees are unaware of their rights, further complicating the potential for self-enforcement (Haque, Sarker, Rahman, Rahman, & Rakibuddin, 2020). Financial constraints also hinder employees’ ability to pursue legal action, as some may lack the means to initiate lawsuits (Syed, 2020b). Furthermore, individuals who do attempt to enforce their rights may fear retaliation from their employers or the stigma of being labeled as troublemakers, which could impact their future prospects in the labor market (Islam, Abbott, Haque, Gooch, & Akhter, 2022). On the other hand, the criminal enforcement mechanism also frequently falls short due to similar reasons. Reliance on victim complaints as the basis for initiating criminal proceedings often results in workers refraining from filing complaints either due to their lack of awareness of their rights or fear of repercussions (Vosko, 2020). Moreover, criminal proceedings entail complex procedures and necessitate a high burden of proof and evidence for justifiable reasons, which can discourage victims from reporting violations by their employers. These inadequacies and system failures in both private law and criminal law enforcement within the labor industry underscore the need for specialized labor law solutions and the importance of robust labor unions in promoting compliance with and enforcement of labor laws. Various studies have shown that strong labor unions can play a crucial role in ensuring employers adhere to legal mandates (Servais, 2022), despite their occasional pursuit of additional benefits beyond what labor laws require (Landau & Howe, 2016). However, it is essential to acknowledge that while labor unions can advocate for employees and monitor compliance in larger, more established firms, they may face limitations in assisting domestic workers or small shop and office staff. Unions may be unable to unionize workplaces with a minimal number of workers, making it impractical to establish their presence there. Consequently, these inherent challenges create opportunities for employers to take risks and disregard labor law compliance.

In numerous instances, employers fail to fulfill specific obligations as mandated by labor law, such as neglecting to pay overtime or providing wages below the minimum wage requirement (Garnero, 2018). Research indicates that certain employee groups, such as migrant workers, women, minorities, unskilled workers, and part-time employees, are particularly vulnerable and often subjected to more violations than others (Fine & Shepherd, 2021). It has been observed that, within various sectors in Bangladesh, workers toil tirelessly from dawn till dusk to sustain themselves, yet their remuneration falls short of meeting basic necessities such as food, healthcare, clothing, shelter, and education, despite their prolonged work efforts (Syed, 2020a). Particularly in the garment industry, workers face inadequate safety measures, lack of insurance policies, welfare provisions, and insufficient compensation for workplace injuries, in contravention of labor legislation (Moin, Sakib, Araf, Sarkar, & Ullah, 2020). Female workers, in particular, encounter physical and sexual harassment at their workplaces (Tejani & Fukuda-Parr, 2021). Moreover, they face discrimination concerning desired job placements, salaries, and promotions based on their skills and competencies (Haque, Sarker, Rahman, Rahman, & Rakibuddin, 2020). Maternity and leave benefits, as stipulated by law, are often denied to them (Akter, 2021), and in some cases, they are unlawfully compelled by employers to work night shifts or late hours (Akter, 2021). Furthermore, many workers are employed without formal appointment letters, leading to job insecurity and the risk of losing employment without prior notice (Syed, Bhattacharjee, & Khan, 2021; Kabeer, Huq, & Sulaiman, 2020; Ashraf, & Prentice, 2019).

One might inquire whether the current scenario in Bangladesh is a new occurrence. The answer is negative; however, there are compelling reasons to suspect that the situation has exacerbated in recent years, attributable to various factors. Bangladesh has experienced a significant increase in industrialization and globalization over the past decade, yet its compliance standards and codes of conduct have not kept pace with this evolution (Rahman & Chowdhury, 2020). Consequently, several industrial catastrophes have been observed in the last decade. Noteworthy examples include the Tazreen Fashion fire in 2012, which resulted in 112 fatalities and approximately 200 injuries (Roy, 2022; Vanpeperstraete, 2021), and the Rana Plaza collapse in 2013, claiming the lives of 1137 individuals and leaving over 2500 injured (Mansoor et al., 2021; Syed, 2020a). More recently, the Hashem Foods Factory fire in 2021 resulted in the loss of 52 workers' lives and injured 20 others (Syed & Ikra, 2022), while the BM Container Depot explosion claimed 49 lives and caused over 450 injuries (Syed & Ikra, 2022), shedding light on the country’s poor track record in compliance.

Furthermore, globalization has contributed to certain trends, one of which is the proliferation of external collaborations, including outsourcing, subcontracting, and supply chains, involving foreign buyers and multinational companies (Rahman & Chowdhury, 2020). For instance, many companies in developed nations shift their manufacturing operations to developing countries like Bangladesh to circumvent high costs and stringent labor regulations. This poses a paradox for the Bangladeshi government, as enforcing labor laws and pro-labor policies may discourage investment in manufacturing, potentially impacting exports, economic growth, and employment. Moreover, the issue becomes complex when considering whether extraterritorial companies can be held accountable in their respective jurisdictions for any wrongdoing, especially if they are not effectively held responsible in Bangladesh, potentially invoking principles of strict liability. Given this complexity, many victims are hesitant to file lawsuits against large foreign corporations, creating uncertainty surrounding the attainment of justice.

Additionally, the rise of smaller and less established factories can be attributed to global competition, fulfilling the demands of the local market without engaging in product exports, which exempts them from adhering to the code of conduct required by overseas buyers. As a consequence, these factories often unexpectedly violate both the code of conduct and labor laws (Rahman & Chowdhury, 2020). Moreover, the rapid expansion of industrial activities has led to a substantial increase in employment opportunities. However, a significant portion of the newly hired workforce comprises illiterate women and teenagers hailing from remote and impoverished rural areas (Syed & Mahmud, 2022). Due to their limited understanding of labor laws and their rights, labor law violations have been on the rise. Also, in recent years, several sectors have transitioned towards non-standard alternative employment arrangements, including part-time work and remote work from home. Such non-standard employment arrangements often hinder interpersonal contact between employees, making it difficult for them to unionize and acquire awareness of labor laws and their entitlements. This, in turn, contributes to an escalation in labor law violations.

In light of the aforementioned challenges, the following research question has been posed:

-

How can we enhance compliance with and enforcement of labor laws to safeguard labor rights in Bangladesh?

Conceptual framework

There are two overarching approaches commonly considered to prevent or minimize violations of labor law, as outlined by Davidov (2021). The first approach, referred to as the “ex-ante” method, is aimed at preventing violations before they occur by building awareness and compliance among stakeholders. The second approach, known as the “ex-post” method, involves detecting and penalizing violations after they have taken place. The latter often includes administrative penalties, restrictions on company privileges, and other strategic criminal mechanisms, sometimes severe criminal measures.

In the context of fostering compliance, some advocate for self-regulation or voluntary compliance rather than relying solely on punitive sanctions. The “compliance model” emphasizes proactive teaching and awareness-building among employers to promote adherence, while the “deterrence model” focuses on punitive actions after violations are identified (Vosko et al., 2021). However, it is recognized that a strict “command and control” approach, which solely relies on punishment for non-compliance, may be impractical, costly, and ineffective (Davidov, 2021).

Despite having labor laws that permit criminal sanctions, including penalties for severe violations causing worker injuries or deaths, evidence suggests that the mere existence of such laws on paper is insufficient to address violations effectively (Syed & Ikra, 2022). For these laws to be truly effective, they must be complemented by robust and strategic compliance mechanisms.

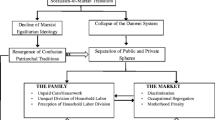

To address this issue and enhance compliance, I propose a novel approach that incorporates cost-benefit analysis from employers’ perspectives (Fig. 1). The premise is that if we strategically increase violation costs compared to the costs of compliance and enforcement of the law, then employers will automatically follow the law. However, it is important to note that this strategic approach does not undermine the significance of rigorous punishment theories (ex-post); rather, it recognizes that laws without effective compliance mechanisms may not be practical or deterrent enough, particularly in developing countries like Bangladesh.

The study is aimed at understanding employers’ perspectives to identify strategies for enhancing compliance. The blended method of cost-effective analysis from employers’ perspectives, along with existing labor policies, can serve as a comprehensive approach to promote compliance with labor laws. Combining collaboration with punitive measures has been found to be the most effective strategy for reducing violations (Schell-Busey, Simpson, Rorie, & Alper, 2016). Therefore, I propose integrating employers’ cost-benefit analysis techniques with current enforcement approaches, such as ex-post measures or punishments, into a unified legislative framework. This approach could offer valuable insights for labor law policymakers in Bangladesh and other jurisdictions in the Asian global south, given their comparable socio-economic and cultural backgrounds.

The cost-benefit analysis framework presented in this study goes beyond traditional strategic enforcement mechanisms, encompassing a wider range of approaches. It incorporates methods that extend beyond those commonly proposed by enforcement agencies, offering a more comprehensive and effective approach to ensure compliance with labor laws.

Minimizing benefits from violation

When an employer evaluates labor laws and becomes aware of the obligations imposed by a particular law, the cost of compliance may lead them to consider the possibility of violating the law. In such a situation, the employer will assess the advantages of non-compliance in comparison to the costs associated with adhering to the law.

This manuscript proposes two strategies to effectively minimize the benefits gained from infractions: (1) enhancing the likelihood of “self-enforcement” and (2) bolstering the capacity of other actors to prevent or restrict violations. Each of these approaches will be discussed in detail subsequently.

Increasing possible self-enforcement by employees

Within this group, four techniques are considered, aligned with Davidov’s (2021) framework. While this list may not be exhaustive, the paper is aimed at proposing a structure for classifying different approaches and highlighting significant methods and their challenges in the context of Bangladesh.

Class actions lawsuit against an employer

A “class action” refers to multiple employees facing the same labor law violation or discrimination at work, uniting to file a combined lawsuit against the employer. When an employer neglects a specific obligation owed to one employee, it suggests a likelihood of similar mistreatment towards others. For instance, imagine workers are required to prepare their workstations 15 minutes before their official start time, but the employer fails to compensate them for this extra work. The cost of those 15 minutes per day may not seem significant for an individual worker with a low salary, discouraging them from legal action due to the associated expenses. However, when a group of workers experiencing the same violation comes together to sue the employer, their combined compensation becomes more substantial, making it more feasible for them to pool their resources and pursue legal action. Consider the scenario where millions of workers suffer unjust terminations and wage deprivations during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is impractical for individual workers to file millions of lawsuits. However, what if all affected workers collectively file a class action suit against the employers?

While such large-scale class actions may seem unlikely in the current context of Bangladesh, they have proven useful in other countries. However, typically employees do not sue their employers while still employed, and most employment-related lawsuits are filed after the employment relationship ends. This weakens the connection between individual employees and reduces the likelihood of a large group filing a joint lawsuit, especially when employees terminate at different times and reside in various locations.

Nevertheless, class actions have become prevalent in many countries. In Israel, for example, the law permits a single employee to represent all similarly affected employees in a lawsuit, offering significant remuneration to the representative plaintiff and their attorney (Class Actions Act, 2006). Although class action lawsuits are not common in Bangladesh, there is a notable precedent. In 2018, a group of garment workers successfully filed a class action lawsuit against their employer for unpaid wages and overtime, resulting in $2.3 million in compensation (Robayet Ferdous Syed, 2023, February 21).

By participating in a class action, similarly situated workers can benefit as if they were parties to the suit, prompting a reevaluation of the cost-benefit ratio for employers. Employers can no longer rely on the assumption that only a minority of employees will sue and that settlements will be for lesser amounts. Instead, they must consider the possibility of paying the total amount owed to all employees, along with compensation for delays and other sums for the representative claimant and their lawyer.

However, two obstacles may hinder the successful implementation of class actions to some extent. The first challenge arises from court resistance or reluctance to deviate from conventional litigation approaches. In some countries, lawmakers have been hesitant to fully recognize the potential of class actions or have limited their scope (Waas, 2021). However, in cases where legislation allows for extensive use of class actions, courts must carefully consider and approve their application. A study indicates that judges must assess whether a class action is the most effective and equitable way to resolve a dispute while ensuring adequate representation of all affected parties (s. 8, Class Actions Act, 2006). Unfortunately, representative plaintiffs often face difficulties in overcoming this obstacle. Labor courts, in many instances, appear unwilling to embrace class actions, believing that an absent party in the suit might lead to inadequate representation and unresolved issues. Notwithstanding, employers need to consider the potential for class actions in their cost-benefit analyses, but this can only happen if a significant number of class actions are authorized without excessive procedural barriers.

The second challenge in implementing class actions lies in their relationship with labor unions. Initially developed for consumer law, class actions allowed multiple customers with small claims to litigate separately. However, labor law already provides a collective action mechanism through unions that act on behalf of multiple employees. In workplaces with active and unionized employees, compliance with labor laws is generally expected (Landau & Howe, 2016). However, in such cases, class actions may be perceived as disruptive. They represent an attempt by a single worker to act on behalf of all similar-status employees, even when another entity (the union) is already representing them. Unions, being more democratic and representing workers on a long-term basis, may have wider considerations compared to individual class action representatives. In some countries, such as Israel, legislation specifically prohibits class lawsuits by employees covered under a collective agreement, ensuring that class actions do not compete with unions (s. 10(3), Class Actions Act, 2006).

In Bangladesh, the presence and performance of unions are limited in many sectors, and the process of unionization is complicated under current labor law, with various rules and regulations to follow [s. 179(2), Bangladesh Labor Act 2006, (BLA2006)]. Moreover, certain sectors, such as domestic work, do not consider workers as labor under the law (s. 1(4), BLA2006). Unions are mainly found in government and semi-government organizations, as well as in formal and reputable industries such as the 100% export-oriented industry, and reputed national and international organizations. Due to limited resources and obstacles, many unions in Bangladesh struggle to organize in factories, and the government’s actions and employer resistance hinder their efforts (Kabeer, Huq, & Sulaiman, 2020). Consequently, many unions in Bangladesh are inactive and passive, and they hesitate to negotiate with employers. The strength of employers’ associations, often linked to the ruling political party, adds to the perception that they are more influential than labor unions (Syed, 2020). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the industrialization and globalization of the state over the last decade have led to the rise of smaller and less established factories, along with increased external collaborations of large factories through outsourcing, subcontracting, and supply chains. These collaborations often employ only a small number of workers, making it impractical to form unions.

In such a context, class actions become a more realistic prospect to prevent violations in Bangladesh. Additionally, class action lawsuits may serve to activate inactive unions and encourage them to play a more active role in advocating for workers’ rights.

Compensatory damages

Class action lawsuits present an effective means of increasing compliance with labor rules, but their applicability is limited to specific cases where a large group of employees has experienced the same violation. In addition to the previously mentioned obstacles, such lawsuits might not be financially viable for a single employee or a smaller group due to the costs involved. As a result, an alternative approach to deter frequent minor violations by employers is the use of compensatory damages. These damages are assessed in legal proceedings to penalize negligent defendants, regardless of the scale of the violation (Johnson, Schwab, & Koval, 2022). To effectively deter minor infractions, compensatory damages must be substantial enough to outweigh the potential benefits of violating the law, prompting employers to carefully assess the costs and benefits of their actions.

Significantly, compensatory damages can serve a dual purpose. Firstly, they can incentivize workers to sue, even for relatively minor violations, and secondly, they increase the financial burden on employers. My primary focus is on the first impact, as compensatory damages can make it more advantageous for employees to seek legal recourse, potentially increasing self-enforcement and reducing the employer’s ability to profit from violations. However, in cases where employers already face penalties through criminal or administrative procedures for the same breach, compensatory damages may not be justifiable within Bangladesh’s legal system. Nevertheless, as the majority of breaches often go unpunished, compensatory damages can address the lack of deterrence and encourage compliance (Davidov, 2021).

In certain countries, labor courts have the authority to award compensatory damages in cases related to unpaid or delayed wages, employers failing to provide employment terms notice, termination of employees for reporting illegal activities, prevention of employees from joining unions, or unjustified denial of sitting at work (Davidov, 2021). Some of these provisions have been implemented in Israel recently, indicating the legislature’s recognition of the enforcement problem and the potential role of compensatory penalties (Davidov, 2021). Additionally, legislation addressing workplace discrimination empowers labor tribunals to award damages for non-monetary harms, including punitive damages in some discrimination cases (Sharon Plotkin v. Eisenberg Brothers Ltd, 1997).

In Bangladesh, employers could be subject to compensatory damages for violating workers’ rights concerning leave, minimum wage, overtime payment, weekly holidays, excessive unpaid work, prolonged standing, mandatory night-shift work, and similar infractions. The amount of compensatory damages should surpass the gains derived from such violations, sending a clear message to employers that compliance is more favorable than breaking the law. By incorporating compensatory damages as an effective mechanism, labor law enforcement can be strengthened, leading to improved compliance and protection of workers’ rights.

Easy access to courts

The ability of workers to pursue claims in court is crucial for promoting compliance with labor laws. If the process of bringing a case to court is difficult or unlikely to result in a fair resolution, employers may perceive self-enforcement as improbable, leading to frequent violations of labor law. Therefore, the establishment of a separate labor court system is of paramount importance. Such a specialized system is designed to handle worker claims and is more attuned to workers’ issues, making it more accessible than the general court system.

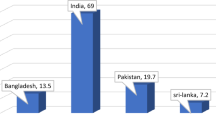

In Bangladesh, there is a separate labor court system, but the number of labor courts is inadequate with only seven in total, along with two appellate tribunals, serving a vast workforce of 69.8 million people (Hoque, 2014). Additionally, the judges assigned to these courts are generally not trained in labor and industrial relations matters, and they typically spend only a brief period, about two or three years, in labor courts before being transferred elsewhere. This lack of expertise and experience can lead to delays in hearings, making it harder for employees to obtain appropriate remedies. As a result, employers may perceive that workers will not receive justice in labor courts, potentially encouraging them to violate labor laws. To address this issue, it is crucial to increase the number of labor courts and provide specialized training in labor and industrial relations law for the appointed judges. This will ensure that workers have a fair chance of obtaining remedies for labor law violations. In Bangladesh, workers do not need to pay court fees for filing lawsuits in labor courts or tribunals, but they do need to bear the costs for appeals. While lawyers assist workers throughout the lawsuit procedures, the system lacks practicality and effective mechanisms to ensure access to justice.

In contrast, the United Kingdom previously required workers to pay court fees for employment tribunals and appeals, which proved to be a significant barrier. The UK Supreme Court found that these fees led to a notable decrease in the number of claims, violating the constitutional right to access the courts without justifiable reasons. Consequently, in the case of R (UNISON) v. Lord Chancellor in 2017, the Fees Order was declared unconstitutional.

Besides, arbitration provisions, where employees agree to resolve any claims against their employer before an arbitrator, can pose a significant barrier to accessing courts. This is because the arbitrator's decision is usually final and cannot be appealed, as stated in the Bangladesh Labor Act of 2006 (s. 210 (16), BLA2006). In many cases, employers have substantial control over the arbitration process and the arbitrator's decision, which can undermine the legitimacy of workers' claims. Some countries, such as Israel, consider such contractual clauses invalid, as they believe that certain rights should not be subjected to arbitration (s. 3, Arbitration Act, 1968, Israel). On the other hand, the United States Supreme Court has upheld the validity of arbitration agreements (Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, 2018), despite the power disparity between the parties and the negative impact this ruling has on employees’ ability to enforce their rights. Furthermore, this ruling eliminates the possibility of class action lawsuits, which is a major concern.

A recent incident in Canada highlights an extreme version of this issue. Uber forced all its Canadian drivers to sign an agreement that required them to resolve any claims through arbitrators in the Netherlands and pay a hefty $15,000 “administrative fee” for such claims. This fee is in addition to other expenses, such as attorney fees, that the drivers would have to bear while filing a claim in a foreign country. Clearly, this exorbitant contractual provision was designed to deter drivers from filing claims against Uber. As Uber classified its drivers as independent contractors, the contract containing the arbitration clause was not considered an employment contract. However, David Heller, the plaintiff, filed a class action lawsuit asserting that the drivers are, in fact, employees. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the clause was unreasonable and consequently null and unenforceable, allowing the class action suit to proceed before a Canadian court (Uber Technologies Inc. v. Heller, 2020).

Unlike developed countries like Canada, many workers in Bangladesh are illiterate, with a significant portion being women (especially garment workers) from remote rural areas. Due to their lack of awareness about labor rights, employers often violate labor laws with impunity. Therefore, imposing disclosure duties on different stakeholders could be an effective mechanism for promoting compliance with labor law, as discussed in the following section.

Disclosure duties

Employer disclosure obligations can effectively increase the likelihood of self-enforcement, thereby reducing employers' potential to benefit from breaching labor laws and promoting compliance. These obligations may include requirements for employers to inform workers about the law and their rights. Some jurisdictions have implemented such requirements. For example, in Israel, employers are mandated by statutes to inform workers about the minimum wage (s. 6B, Minimum Wage Act, 1987) and sexual harassment (s. 7, Prevention of Sexual Harassment Act, 1998). In countries like South Africa, Hungary, Vietnam, and Poland, labor inspection agents are responsible for providing information on labor laws, among other duties. This approach has been cited by Syed (2020b) as an example of how employer disclosure obligations can enhance compliance by increasing the likelihood of self-enforcement and reducing employers' gains from breaching labor laws.

In Bangladesh, relevant employers’ associations, such as the Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) and Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA), could be held accountable for informing workers of their rights. Additionally, the law could require employers to provide personalized information to employees about their rights, such as the number of hours worked [Notice to Employees and Prospective Employees Act, 2002 (Israel)], the remaining number of vacation days, and other relevant details [s. 24, Wage Protection Act, 1958 (Israel)]. This information is crucial for employees to understand their rights fully and identify any violations.

However, one might question whether addressing noncompliance with labor rules by enacting additional laws could lead to further noncompliance. To address this challenge, creating incentives for compliance, particularly concerning disclosure duties, becomes essential. Employers must share the necessary information for employees to assert their rights effectively. If an employer fails to disclose this information, the burden of proof may shift to the employer to demonstrate that the worker’s claims about hours worked or holidays taken are incorrect. In promoting compliance with labor laws, employers can reduce legal risks by addressing uncertainties through the proper fulfillment of disclosure responsibilities. By doing so, employers ensure that workers are well-informed about their rights, consequently increasing the likelihood of self-enforcement. To further enhance compliance, additional measures can be put in place, such as providing employees with a comprehensive notice outlining the terms and conditions of employment and their rights at the outset of their employment. Additionally, employers can be obligated to furnish a detailed wage slip that includes information on overtime pay, vacation pay, travel expenses, and other relevant details mandated by labor laws. Employers bear a legal obligation to inform workers about their regular working hours, including any overtime hours, while maintaining accurate records related to this. Failure to comply with this obligation may lead to employers being held liable for up to 12 hours of overtime (the maximum allowed in a week) if workers claim otherwise and the employers are unable to provide contrary evidence.

The recently introduced “EU Directive on Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions” echoes similar provisions discussed earlier. The Directive requires employers to furnish documented information to employees, with Member States instructed to favorably consider employee claims in cases of employer non-compliance. Furthermore, the Directive introduces a new clause pertaining to on-demand workers, obliging EU Member States to assume that such workers have a minimum number of paid hours based on their average working hours over a specific period (see art. 11 and 15 of the EU Directive). Emphasizing the need to strengthen the enforcement of labor laws (see s. 39 of the preamble), this Directive justifies these significant provisions aimed at ensuring greater transparency and protection of workers’ rights. Overall, employing disclosure duties and supplementary measures can lead to better-informed employees and heightened self-enforcement, thereby fostering a culture of adherence to labor laws and ensuring greater protection of workers’ rights.

Other actors to prevent or restrict violations

In this section, we explore four distinct techniques centered around “other actors,” namely, unions, employee centers, parent or lead firms, and independent monitors, which are designed to prevent and restrict labor law violations. These approaches are commonly referred to as public-private compliance programs, as they involve both state and non-state actors (Hardy & Ariyawansa, 2019). All these measures have one main goal: to reduce the financial benefits employers might get from breaking labor laws. By doing this, they aim to discourage employers from making choices that could lead to such violations in the first place.

Labor unions

Among the various entities aimed at combating labor law violations, labor unions stand out as a prominent force. As supported by empirical evidence, unionized workplaces have demonstrated a significant reduction in the likelihood of labor breaches (Landau & Howe, 2016). Unions play a crucial role in providing employees with vital information about their rights, assisting them in assessing whether they are receiving their entitlements, and advocating on their behalf with employers to seek redress in case of violations. Moreover, unions offer a fundamental aspect of job security, which is essential for enabling employees to assert their rights effectively (Davidov, 2021).

Notably, unions can act as powerful enforcers in preventing unjust terminations by employers. In the United States, for instance, the job security protections established through collective agreements significantly impact employees’ ability to exercise their rights. Even in countries with laws safeguarding workers from unfair dismissals, the presence of unions can further reduce the occurrence of such unfair practices. This is because enforcement agencies often do not proactively pursue claims on behalf of workers, while unions consistently act to ensure access to legal remedies for victims.

Therefore, States should recognize the vital role of unions in preventing enforcement crises and upholding labor rights. However, in many countries, a debate persists over whether unions should be permitted to initiate lawsuits as plaintiffs on behalf of individual workers whose rights have been violated (Waas, 2021). While it is clear that unions can legally take action in collective disputes, the scope of their involvement in cases where employers have violated statutory obligations towards specific workers remains less clear. In Bangladesh, for instance, unions are not allowed to file lawsuits for the violation of an individual worker’s rights. Allowing them to do so could empower specific employees to remain anonymous in the struggle against powerful employers.

The question of whether collective actions, such as strikes, should be permitted for enforcing labor regulations is a separate but interconnected matter. In less extreme situations, it might be argued that strikes should be allowed to enforce compliance with labor laws when filing a lawsuit is not a feasible solution. However, it is essential to exercise caution and consider that labor laws provide a “floor” of non-negotiable fundamental rights (Davidov, 2020). In conclusion, the presence of active unions in the context of Bangladesh is indispensable for upholding labor rights effectively.

Pro bono for workers or worker centers

While unions are effective in enhancing compliance, their membership has declined in many countries, and Bangladesh is no exception, where workers are often discouraged from joining unions. Additionally, in certain types of workplaces, unionization may be impractical. Therefore, worker centers can serve as an alternative mechanism to prevent labor law violations. These centers are non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that specialize in protecting workers’ rights and often provide assistance to non-unionized, low-wage workers. This concept is particularly prevalent in the United States, where union density is low, but it also exists in other countries (Davidov, 2021). Some worker centers are structured similarly to unions, focusing on worker participation, but they choose not to be classified as unions due to various reasons, often related to legal restrictions in specific countries.

In Bangladesh, the government does not have official worker centers to assist workers, but a few NGOs have taken initiatives exclusively for workers. For instance, the Bangladesh Institute of Labor Studies (BILS) is one such organization, and others like the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) and Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) also engage in similar efforts to support workers. However, given the vast number of workers in Bangladesh, more concerted efforts are required to address their needs comprehensively. In addition to the existing NGO initiatives, the establishment of effective “Employees’ Hotlines” in sufficient numbers could play a vital role in supporting and advocating for low-wage workers, especially female and domestic workers in the country. These hotlines should be designed based on worker participation, enabling them to better understand workers’ needs and communicate effectively with them.

However, to strengthen the enforcement of labor rights, NGOs and employee centers heavily rely on donations from concerned individuals and organizations. While their valuable contributions are evident, ensuring their long-term sustainability raises important questions. Firstly, what alternative sources of funding could be explored to support these organizations consistently? Secondly, how can we strengthen the legal and institutional frameworks protecting workers’ rights, allowing NGOs and employee centers to play a complementary role in enforcing those rights, rather than becoming a substitute?

One potential avenue is to consider granting “employee centers” the right to initiate lawsuits. Currently, they can provide legal assistance and representation for employees, but in some cases, granting them the ability to file lawsuits without specifically naming individual employees might be advantageous. Certain countries’ labor laws already allow for such possibilities. For instance, according to the Right to Seating and Suitable Conditions at Work Act (2007) (Israel), a worker, a labor union, or an employee center advocating for workers’ rights may initiate a lawsuit in case of a violation, provided they have obtained the worker's consent. Similarly, the Equal Wage to Female and Male Employees Act (1996) (Israel) permits organizations concerned with women’s rights to file lawsuits with the consent of the affected worker.

Another strategy suggested by experts is fostering cooperation between state enforcement authorities and employee centers (Fine & Gordon, 2010). This collaborative approach has been observed in some US cities, highlighting benefits such as maintaining direct communication with employees in their language and aiding in the collection of information on violations while educating workers. Establishing a more formalized relationship between the government and employee centers, termed “co-enforcement mechanisms” (Amengual & Fine, 2017), could involve providing grants to these centers, supporting their funding and facilitating a more integrated approach. Examples of such cooperation already exist, with some cases receiving state funding (Amengual & Fine, 2017).

Exploring alternative funding sources and strengthening collaboration between state authorities and employee centers can enhance the enforcement of labor rights, ensuring that these organizations continue to play a crucial role in protecting workers’ rights effectively.

Parent company

As previously discussed, the practice of outsourcing and subcontracting has contributed to non-compliance with labor laws in various industries, such as the global garment supply chain. In Bangladesh, the garment manufacturing industry has increasingly relied on outsourcing over the past decades, resulting in a complex network of contractors and subcontractors. This system, while cost-efficient for employers, often leads to lower profit margins for contractors and subcontracts, potentially leading to labor law violations in pursuit of reducing costs. Although buyers or client companies may not be directly responsible for these violations, their purchasing practices can indirectly contribute to the problem. By negotiating lower prices and seeking the lowest-cost contractors, buyers inadvertently create an environment where labor rights can be compromised. However, buyers can play a vital role in promoting compliance and mitigating violations in the supply chain. One approach buyers can take is to pay a fair and reasonable price that enables employers to meet employment costs and provide workers with a living wage. By using their significant buying power, buyers can choose to work only with law-abiding and reputable employers. They can include clauses in their contracts that require full compliance with labor laws and demand guarantees to ensure adherence. Additionally, buyers can leverage their influence by threatening to terminate relationships with factories found in violation of labor laws.

The 2011 Act to Improve the Enforcement of Labor Laws in Israel exemplifies a successful structure of incentives that harnesses the power of buyers. The act holds buyers or client companies accountable for any violations involving cleaning and security workers employed by their suppliers. This encourages buyers to exercise due diligence and ensure their suppliers are compliant with labor regulations. Another approach is for the buyer company to appoint an independent monitoring agency to oversee the working conditions and labor practices of their suppliers. By paying suppliers more than the minimum required by law and actively ensuring compliance, buyer companies can demonstrate a commitment to fair labor practices. Failing to take such actions when violations occur can be considered an offence, not only by the company but also by its managers who could have prevented the violation but chose not to do so (Bogg, Collins, Freedland, & Herring, 2020). By adopting these approaches, buyers can play a pivotal role in improving compliance with labor laws and enforcing workers’ rights in Bangladesh and similar contexts.

One might question the appropriateness of holding one entity accountable for violations committed by another. However, it can be justified if the latter has the ability to prevent such violations. For instance, should lead companies be held responsible for supply chain violations by their contractors? Similarly, should a European company employing Bangladeshi contractors for manufacturing be held accountable for their contractors’ infractions, even if they ensure compliance through adequate payment? Another area of debate is whether franchisors should be held liable for violations by their franchisees. For example, if a company operating a Walmart store violates labor regulations, should Walmart Corporation also bear responsibility? This issue has been a subject of discussion among experts (Hardy, 2016).

Some authors argue that accountability is justifiable only when there is a direct relationship between the client and the employees (Davidov, 2015). In Germany, responsibility is broader, encompassing minimum wage violations in all industries (s. 21 (2), Minimum Wage Act, 2014). Clients who engage contractors and are aware of their or their subcontractors’ violations may be subject to administrative fines. In such cases, it is not unreasonable for clients to have an obligation to ascertain whether their contractors are violating labor rules and to discontinue business with them if they are.

While it may seem like an exception to the usual practice of separating distinct legal entities, such accountability can be justified given the compliance crisis and the imperative of safeguarding workers’ rights in Bangladesh. For franchisors, liability may also apply if their use of the brand name implies a direct operational role (Davidov, 2015). However, extending such liability becomes more challenging when workers are geographically distant from the parent company, and the company lacks control over their working conditions. Nonetheless, some arguments support this form of liability in certain cases (Anner, Bair, & Blasi, 2013). In Bangladesh, many foreign companies and buyers, particularly in the garment manufacturing sector, have close ties with their agents. As a result, it is worth considering whether they can be held responsible under specific circumstances, potentially contributing to preventing violations to some extent.

Parent company liability

Recent developments in England have seen significant progress in the treatment of the corporate veil concerning parent company liability. Rather than piercing the corporate veil, the courts have taken a different approach in tort (negligence) cases where parent companies have been sued for labor rights violations related to the overseas operations of their subsidiaries. In the landmark case of Chandler v. Cape Plc (2012), the House of Lords issued a significant ruling concerning the liability of a parent company in instances of negligence towards its subsidiary’s workers regarding health and safety standards. The court determined that a parent company could be held responsible for negligence if it failed to provide appropriate guidance and advice to its subsidiary regarding the safety of its workforce. This legal obligation stems from the parent company’s duty of care towards the employees of its subsidiary, which arises due to the transfer of a hazardous work system from the parent company to the subsidiary. Since the parent company possesses superior knowledge of the associated risks and how to mitigate them, as well as an understanding of the subsidiary’s reliance on it, it is deemed to bear responsibility for any harm resulting from inadequate safety measures. Subsequently, the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Vedanta Resources Plc v. Lungowe (2019) case assumed even greater significance than the Chandler v. Cape Plc ruling. This decision addressed concerns that the scope of Chandler’s ruling might be confined to specific circumstances within the parent/subsidiary relationship. However, the Vedanta case clarified that standard principles of tort law govern the determination of a parent company's duty of care towards individuals affected by the activities of its subsidiaries, as opposed to a separate set of principles. In the Vedanta case, a group of 2577 members from a Zambian farming community filed a claim due to the detrimental health and livelihood impacts they experienced as a result of toxic waste that had been discharged into their water source by a Vedanta subsidiary, known as the Nchanga Copper Mine. In its ruling, the Court determined that the British parent company, Vedanta, could be held accountable for its failure to provide adequate guidance to its subsidiary concerning waste disposal practices. Despite the legal concept of separate corporate identity, the Court emphasized that there were no exceptional or definitive features inherent in the mere parent/subsidiary relationship that would prevent the imposition of a duty of care on the parent company regarding the subsidiary’s operations (para 54, Vedanta & Another v. Lungowe & Others, 2019). In light of this, the Court outlined four non-exhaustive scenarios in which such a duty might arise. Firstly, a duty of care could arise if the parent company directly assumes control over or jointly manages the activities of its subsidiary. Secondly, if the parent company issues flawed advice or establishes inadequate group-wide policies that are then implemented as standard practice by the subsidiary, it may also be held responsible. Thirdly, if the parent company takes active measures to ensure that the subsidiary enacts relevant policies that may impact health, safety, or the environment, it could be deemed liable. Finally, even if the parent company represents, in published materials or otherwise, that it exercises a level of control or supervision over the subsidiary, regardless of whether this representation is reflected in reality, it may be held accountable (paras 51–53, Vedanta & Another v. Lungowe & Others, 2019).

Further, the Okpabi v. Royal Dutch Shell (2021) case follows the precedent set by the Vedanta decision, solidifying the notion that, under English law, parent companies can be held accountable for their subsidiaries' harmful activities, even those conducted offshore. This liability arises from a direct duty owed by the parent company to those adversely affected by the actions of its subsidiary. The determination of circumstances under which parent companies may be held liable is guided by established principles of ordinary tort law. Consequently, this legal framework allows claimants to seek compensation from the assets of the parent company and also serves as a basis for establishing jurisdiction in the parent company’s home state. The impact of decisions made in English parent company cases is reverberating across other common law jurisdictions. Notably, the case of Four Nigerian Farmers and Milieudefensie v. Shell (2021) heard in the Dutch Court of Appeal referenced the Vedanta case and upheld that Royal Dutch Shell bore a duty of care towards third parties. In this particular instance, the responsibility entailed taking necessary measures to prevent the risk of oil leaks from pipelines situated in Nigeria, which were under the management of its subsidiary, Shell Nigeria.

Furthermore, a recent decision rendered in an English court sheds light on the potential evolution of tort law to accommodate incursions into contractual veils or supply chains. The case of Begum v. Maran (2021) came before the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, wherein the widow of a Bangladeshi ship worker pursued legal action against a British shipbroker. Tragically, the worker had suffered a fatal fall while engaged in the dismantling of an oil tanker at the well-known “ship-breaking” yards in Bangladesh. The sequence of events leading to the incident involved Maran, the shipbroker, selling the oil tanker to a cash broker with the explicit purpose of its demolition. Subsequently, the cash broker further sold the vessel to Bangladeshi shipyards for breaking up (paras 5-14, Begum v. Maran, 2021). The central issue in the case revolved around Maran’s potential liability for the accident that occurred during the shipbreaking process. For the purpose of an interim judgment, it was assumed that Maran possessed awareness, likely due to the price paid by the intermediary, that the oil tanker would ultimately be dismantled in Bangladesh. Furthermore, it was established that Maran was cognizant of the hazardous working conditions prevalent in the Bangladeshi shipyards, thereby incurring a relevant duty of care toward the deceased worker (paras 25–37, Begum v. Maran, 2021).

Besides, an important aspect of the case of Begum v. Maran (2021) involves arguments suggesting that Maran possessed the capacity to arrange the sale of the ship in a manner that would have increased the likelihood of it being delivered to a safer shipyard for dismantling (paras 67–70, Begum v. Maran, 2021). While the case remains unresolved, the Court has recognized that if substantiated, the existence of such a duty of care would signify a noteworthy expansion of current negligence law categories (paras 14, 37, 65, Begum v. Maran, 2021). Nevertheless, this case serves as an illustration of the potential establishment of stringent legal standards that would demand businesses to exercise heightened caution in specific situations, especially concerning known abuses within their supply chains, and to utilize their influence to avoid such practices wherever feasible.

The recent legal developments observed in England hold significant implications for the effective enforcement of a duty to protect, extending beyond national borders. These developments offer potential solutions to the complex challenges associated with holding companies accountable for labor rights violations, particularly the misuse of corporate and contractual barriers to evade responsibility. While the number of cases has been limited, the impact of these legal precedents is already being felt in other countries (Joseph, and Kyriakakis, 2023).

Apart from legal rulings, specialized United Nations agencies have recognized the imperative of safeguarding workers across international borders. One such agency is the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), which oversees the enforcement of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Notably, the CESCR has consistently advocated that states bear the responsibility of regulating the activities of their corporations operating in foreign jurisdictions. This stance is evident in the agency’s General Comment 24 on Human Rights in the Context of Business Activities, wherein it explicitly articulates this position:

“The extraterritorial obligation to protect requires States parties to take steps to prevent and redress infringements of Covenant rights that occur outside their territories due to the activities of business entities over which they can exercise control, especially in cases where the remedies available to victims before the domestic courts of the State where the harm occurs are unavailable or ineffective.”Footnote 1

The United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) is responsible for overseeing and monitoring the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Unlike its counterpart treaty body, it has been less explicit in its recognition of obligations to protect individuals beyond national boundaries. Nevertheless, it has recently approached the stance of the CESCR Committee. In its General Comment 36 regarding Article 6, which addresses the right to life, the UNHRC stated:

“States must take appropriate legislative and other measures to ensure that all activities taking place in whole or in part within their territory and in other places subject to their jurisdiction, but having a direct and reasonably foreseeable impact on the right to life of individuals outside their territory, including activities taken by corporate entities based in their territory or subject to their jurisdiction, are consistent with article 6, taking due account of related standards of corporate responsibility and of the right of victims to obtain an effective remedy.”Footnote 2

In the Yassin et al. v. Canada (2017) case, the UN Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) issued an admissibility decision one year before the release of General Comment 36. This legal proceeding involved a group of Palestinian villagers who filed a claim against Canada, alleging that the country had failed to fulfill its extraterritorial duty to protect them by regulating the actions of two companies registered in Quebec.Footnote 3 Canada had dismissed relevant court proceedings against these companies on procedural grounds. However, it was revealed that the two companies were directly implicated in the construction of illegal settlements and the marketing of condominiums for sale within those settlements in the occupied West Bank. The complainants contended that their fundamental rights, including the right to freedom of movement, privacy, freedom from inhuman treatment, and minority rights, had been violated as a result of these activities.

The UNHRC specified, appropriately:

“The Committee considers that there are situations where a State party has an obligation to ensure that rights under the Covenant are not impaired by extraterritorial activities conducted by enterprises under its jurisdiction (Yassin et al. v. Canada, 2017, para 6.5).”

In the end, the complaint made by the Palestinian villagers was deemed inadmissible by the UN Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) as they failed to provide enough information on Canada’s actual regulation and control over the two companies involved, as well as the impact of their actions on the complainants. Despite this outcome, the recent legal developments suggest that the UNHRC is increasingly willing to hold states responsible for their failure to exercise proper due diligence in regulating the activities of their companies beyond national borders.

Independent monitoring cells

The concept of independent monitoring is the latest example of using a third party—other than the worker and State enforcement agencies—to prevent or reduce violations.

State enforcement agents such as factory inspectors currently operate in Bangladesh, but it is impossible for them to consistently oversee compliance at every workplace. As a result, in-house monitoring cells may be developed to prevent violations. Although there is a legislative provision in Bangladesh to appoint welfare officers (when five hundred or more workers are employed) to monitor and promote workers’ rights [s. 89 (8), BLA2006], welfare offices remain inactive since they are not independent and work as employees of the same company (Hasan et al., 2020).

To make the monitoring effective, the government could establish “Special Monitoring Cells (SMCs)” inside factories, as well as “Apex Monitoring Cells (AMCs)” to oversee the SMCs and working conditions overall (Syed et al., 2014). Given the severe violations of building and fire safety regulations in Bangladesh, a “Special Approval Authority (SAA)” for building and infrastructure may be necessary to prevent further violations. Specific sectors and a sufficient number of SMCs based on the area could be established to monitor informal workers.

In addition, there should be an increase in the number of inspectors in their current form. The Ministry of Labor should strictly monitor them to ensure that they work without bias when visiting factories and interviewing workers. Inspectors should use the observation method to gather information.

One may argue that all these processes will be costly and burdensome for both employers and governments. However, I oppose this argument with two main points. First, when workers feel that they have job security and their rights are protected, their work efficiency will increase, and this will lead to higher production levels. From an employer’s perspective, this cost-benefit analysis makes it worthwhile to comply with laws.

Second, ethical buyers would surely seek out compliant factories to place their orders. If they believe that the state is committed to upholding workers’ rights and that workers are able to enjoy their labor rights to the fullest, they would be less likely to shift their orders to other countries. As a result, the state, employers, and workers would all benefit greatly.

In some countries, companies have implemented internal monitoring systems as part of enforceable undertakings. This means that companies voluntarily agree to monitor or supervise themselves as part of a settlement with an enforcement agency, which can reduce their penalties for labor law violations (Hardy & Howe, 2013).

The most difficult aspect of such internal monitoring is maintaining its independence. It cannot be effective unless the monitors are entirely independent of the employer and those who pay their fees. Therefore, SMC, AMC, and SAA should consist of professionals who are sufficiently trained and able to perform their duties ethically.

Also, a possible solution would be to give the authority to workers through the process of their representatives to select monitors from a government-supplied list. Allowing employee centers to perform this service may be an alternative solution. At the international level, several brands have voluntarily engaged monitors to lend legitimacy to the monitoring procedure.

In Bangladesh, the Accord, a European Buyers Association, and the Alliance, a North American Buyers Association, were independent monitors of the global garment supply chain industry regarding fire and occupational safety in Bangladesh. Unfortunately, their contract for monitoring this industry has not been renewed since December 2018.

Conclusion with policy implications

The enforcement of labor laws is crucial to ensure their effectiveness and protect the rights of employees. However, determining the most effective mechanisms for compliance and enforcement is an ongoing debate. The current labor laws in Bangladesh are aimed at preventing violations and penalizing offenders, but recent intensification of violations suggests that there might be gaps in their efficacy.

This study focuses on finding alternative techniques to minimize the benefits of violating labor laws. By introducing new compliance mechanisms, employers’ cost-benefit analysis can be influenced, encouraging them to comply with the law. The manuscript has discussed eight strategies under the heading of “minimizing benefits from violation,” which are further divided into two subsets: “increasing possible self-enforcement by employees” and “contributions from other actors to stop violation.” Each subset comprises four individual techniques designed to minimize violations.

It is important to note that the cost-benefit analysis presented in this study offers an additional approach to enhancing compliance with labor laws. These methods do not undermine the existing ex-post and ex-ante mechanisms but rather complement them. While the current mechanisms may have limitations in fully preventing violations, the cost-benefit techniques, combined with the existing mechanisms, can contribute to reducing violations and improving overall compliance. Achieving and maintaining compliance is an ongoing effort that requires continuous and comprehensive strategies.

In conclusion, to promote compliance with labor laws in Bangladesh and protect the interests of employees and society, a multi-faceted approach that combines various enforcement mechanisms and cost-benefit analysis is necessary. By continuously evaluating and refining these strategies, the goal of creating a fair and just working environment can be better achieved.

Limitation of the study

This study introduces a new compliance and enforcement mechanism for labor laws in Bangladesh, employing a cost-benefit analysis from employers’ perspectives, and proposes it as a complementary approach to the existing labor policies.

Recommendation for further research

To strengthen the argument and gain a more comprehensive understanding, further empirical or fieldwork studies on compliance with and enforcement of labor laws in Bangladesh are recommended.

Data availability

No data and materials were used in this study.

Notes

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has provided guidance on extraterritorial obligations in General Comment 24, which can be found in the document E/C.12/GC/24 (2017), specifically in paragraphs 30–31. Additionally, the Maastricht Principles on the Extraterritorial Obligations of States in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2011) provide further information on this topic. The Maastricht Principles can be accessed at the following website: https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/maastricht-eto-principles-uk_web.pdf.

UNHRC, General Comment 36, CCPR/C/GC/36 (2019), para. 22.

The complainants used the language of Article 2(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) to describe Canada's actions, referring to it as a failure to "ensure respect" for certain rights. This is evident in Yassin et al. v. Canada, where the complainants also referred to Canada’s “extraterritorial duty to guarantee” certain rights. (See Yassin, paragraph 3.2 and 3.5 for further details.)

References

Akter, S. (2021). The maternity leave and cash benefit payment system for Readymade Garment (RMG) Sector of Bangladesh. ABC Research Alert, 9(1), 09–14.

Amengual, M., & Fine, J. (2017). Co-enforcing labor standards: the unique contributions of state and worker organizations in Argentina and the United States. Regulation & Governance, 11(2), 129–142.

Anner, M., Bair, J., & Blasi, J. (2013). Toward joint liability in global supply chains: addressing the root causes of labor violations in international subcontracting networks. Comp. Labour Law & Policy Journal, 35, 1.

Ashraf, H., & Prentice, R. (2019). Beyond factory safety: labor unions, militant protest, and the accelerated ambitions of Bangladesh’s export garment industry. Dialectical Anthropology, 43(1), 93–107.

Beerbaum, D. O. (2021). Applying agile methodology to regulatory compliance projects in the financial industry: a case study research. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3834205

Bogg, A., Collins, J., Freedland, M., & Herring, J. (Eds.). (2020). Criminality at Work (p. 431). Oxford University Press.

Bogg, A., Costello, C., Davies, A. C., & Adams-Prassl, J. (Eds.). (2015). The Autonomy of Labour Law. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Davidov, G. (2015). Indirect employment: should lead companies to be liable? Comparative Labour Law & Policy Journal, 37, 5.

Davidov, G. (2020). Non-waivability in Labour Law. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 40(3), 482–507.

Davidov, G. (2021). Compliance with and enforcement of labour laws: an overview and some timely challenges, 3/2021 Soziales Recht 111-127. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3861150

Del Punta, R. (2021). Compliance and enforcement in Italian Labour Law. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 37(2/3), 247–268.

Fine, J., & Gordon, J. (2010). Strengthening labor standards enforcement through partnerships with workers’ organizations. Politics & Society, 38(4), 552–585.

Fine, J., Galvin, D. J., Round, J., & Shepherd, H. (2021). Wage theft in a recession: unemployment, labour violations, and enforcement strategies for difficult times. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 37(2/3), 107–132.

Garnero, A. (2018). The dog that barks doesn’t bite: coverage and compliance of sectoral minimum wages in Italy. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 7(1), 1–24.

Grgurev, I. (2021). Labour law in Croatia. Kluwer Law International BV.

Haque, M. F., Sarker, M., Rahman, A., Rahman, M., & Rakibuddin, M. (2020). Discrimination of women at RMG sector in Bangladesh. Journal of Social and Political Sciences, 3(1), 112–118.

Hardy, T. (2016). Who should be held liable for workplace contraventions and on what basis? Australian Journal of Labour Law, 29, 78–109.

Hardy, T., & Ariyawansa, S. (2019). Literature review on the governance of work. International Labour Organization.

Hardy, T., & Howe, J. (2013). Too soft or too severe? Enforceable undertakings and the regulatory dilemma facing the Fair Work Ombudsman. Federal Law Review, 41(1), 1–33.

Hasan, A. M., Smith, G., Selim, M. A., Akter, S., Khan, N. U. Z., Sharmin, T., & Rasheed, S. (2020). Work and breast milk feeding: a qualitative exploration of the experience of lactating mothers working in ready-made garments factories in urban Bangladesh. International Breastfeeding Journal, 15(1), 1–11.

Hoque, R. (2014). Courts and the adjudication system in Bangladesh: in quest of viable reforms. In J. R. Yeh & W. C. Chang (Eds.), Asian courts in context. Cambridge University Press.

Islam, M. A., Abbott, P., Haque, S., Gooch, F., & Akhter, S. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on women workers in the Bangladesh garment industry. The University of Aberdeen and the Modern Slavery and Human Rights Policy and Evidence Centre (Modern Slavery PEC).

Johnson, M. S., Schwab, D., & Koval, P. (2022). Legal protection against retaliatory firing improves workplace safety. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–53.

Joseph, S., & Kyriakakis, J. (2023). From soft law to hard law in business and human rights and the challenge of corporate power. Leiden Journal of International Law., 36(2), 335–361. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156522000826

Kabeer, N., Huq, L., & Sulaiman, M. (2020). Paradigm shift or business as usual? Workers’ views on multi-stakeholder initiatives in Bangladesh. Development and Change, 51(5), 1360–1398.

Landau, I., & Howe, J. (2016). Trade union ambivalence toward enforcement of employment standards as an organizing strategy. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 17(1), 201–227.

Mansoor, N., Rudhof-Seibert, T., & Saage-Maaß, M. (2021). Pakistan’s “Industrial 9/11”: transnational rights-based activism in the garment industry and creating space for future global struggles. In Transnational Legal Activism in Global Value Chains (pp. 107–120, 108). Springer.

Moin, A. T., Sakib, M. N., Araf, Y., Sarkar, B., & Ullah, M. A. (2020). Combating COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: a memorandum from developing countries.

Rahman, K. M., & Chowdhury, E. H. (2020). Growth trajectory and developmental impact of ready-made garments industry in Bangladesh. In Bangladesh's Economic and Social Progress (pp. 267–297). Palgrave Macmillan.

Syed, R. F. (2023). COVID-19 pending benefits class action lawsuit. The Daily Observer https://www.observerbd.com/news.php?id=408116

Roy, S. K. (2022). Implementation of safety measures under labor law in a factory established in Bangladesh, 1-16.

Schell-Busey, N., Simpson, S. S., Rorie, M., & Alper, M. (2016). What works? A systematic review of corporate crime deterrence. Criminology & Public Policy, 15(2), 387–416.

Servais, J. M. (2022). International labour law. Kluwer Law International BV.

Syed, et al. (2014). Security and safety net of garments worker: need for amendment labour law. National Human Right Commission, Bangladesh, Technical Report. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4907.5200

Syed, R. F. (2020). Comparative implementation mechanism of minimum wage policy with adherence to ILO: a review of the landscape of garment global supply chain industry in Bangladesh. E-Journal of International and Comparative LABOUR STUDIES, 9(2), 57–81.

Syed, R. F. (2020a). Ethical business strategy between east and west: an analysis of minimum wage policy in the garment global supply chain industry of Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 9(2), 241–255.

Syed, R. F. (2020b). Theoretical debate on minimum wage policy: a review landscape of garment manufacturing industry in Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 9(2), 211–224.

Syed, R., Bhattacharjee, N., & Khan, R. (2021). Influential factors under labor law adhere to ILO: an analysis in the fish farming industry of Bangladesh. SAGE Open, 11(4), 21582440211060667.

Syed, R. F., & Ikra, M. (2022). Industrial killing in Bangladesh: state policies, common-law nexus, and international obligations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 1–18.

Syed, R. F., & Mahmud, K. T. (2022). Factors influencing work-satisfaction of global garments supply chain workers in Bangladesh. International Review of Economics, 69(4), 507–524.

Tejani, S., & Fukuda-Parr, S. (2021). Gender and COVID-19: workers in global value chains. International Labour Review, 160(4), 649–667.

Vanpeperstraete, B. (2021). The Rana Plaza Collapse and the case for enforceable agreements with Apparel Brands. In Transnational legal activism in global value chains (pp. 137–169). Springer.

Vosko, L. F. (2020). Closing the enforcement gap: improving employment standards protections for people in precarious jobs (p. 2). University of Toronto Press.

Vosko, L. F., et al. (2021). A model regulator? Investigating reactive and proactive labour standards enforcement in Canada’s federally regulated private sector. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 37(2/3), 161–182.

Waas, B. (2021). Enforcement of labour law: the case of Germany. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 37(2/3), 225–246.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Statues

Arbitration Act 1968, s. 3; (Israel)

Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006 (BLA2006), s 1(4); 89 (8); 179(2); 210 (16).

Class Actions Act, 2006, s. 8; 10 (3), (Israel).

Employment Tribunals and the Employment Appeal Tribunal Fees Order, (2013), (UK).

Equal Wage to Female and Male Employees Act, 1996, (Israel).

EU Directive 2019/1152 of the European Parliament and of the Council, (20 June 2019), art. 11; 15; s. 39 of the Preamble.

Minimum Wage Act, (1987), s. 6B, (Israel)

Minimum Wage Act of 2014, s. 21 (2) (German).

Notice to Employees and Prospective Employees Act, (2002), (Israel)

Prevention of Sexual Harassment Act, (1998), s. 7, (Israel)

Right to Seating and Suitable Conditions at Work Act, 2007, (Israel)

Wage Protection Act of 1958, s. 24, (Israel).

Case Laws

Begum v. Maran [2021] EWCA Civ 326.

Chandler v. Cape plc [2012] EWCA Civ 525.

Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, 584 U.S. [2018].

Four Nigerian Farmers and Milieudefensie v. Shell (29 January 2021) The Hague Court of Appeal.

Okpabi v. Royal Dutch Shell [2021] UKSC 3.

R (UNISON) v. Lord Chancellor, [2017] UKSC 51

Sharon Plotkin and others v. Eisenberg Brothers Ltd, N.L.C. 56/3-129, P.D.A. 23, 481.

Uber Technologies Inc. v. Heller, [2020] SCC 16.

Vedanta & Another v. Lungowe & Others [2019] UKSC 20.

Yassin et al. v. Canada, UN Doc. CCPR/C/120/D/2285/2013 (7 December 2017).

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Syed, R.F. Compliance with and enforcement mechanism of labor law: cost-benefits analysis from employers’ perspective in Bangladesh. Asian J Bus Ethics 12, 395–418 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-023-00179-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-023-00179-0