Abstract

Disability is one of the key public health issues in India and the burden will increase given the trend of an aging population. People with disabilities experience greater vulnerability as they may develop secondary health issues. They face various barriers while accessing health services. This is a major ethical concern. In this article, we frame the barriers to healthcare provision to persons with disabilities and propose an ethical framework to address these barriers. This ethical framework is derived from the basic ethical principles of justice, fairness, trust, solidarity, stewardship, proportionality, and responsiveness. The framework proposes strategies to address these barriers to healthcare service delivery for persons with disabilities in India.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, over 15% of the world’s population lives with some form of disability either permanent or temporary (WHO 2021). People with disabilities experience greater vulnerability as they may develop secondary health issues such as ulcers, diabetes, hypertension, and respiratory diseases such as COPD (Senjam and Singh 2020; Gupta et al. 2014; Zuurmond et al. 2019; Balarajan et al. 2011). Disability is one of the key public health issues in India and the burden will increase given the trend of an aging population and increasing trend in non-communicable diseases (Kumar et al. 2012). A study conducted in India reported that people with disabilities are at a 4.6 times higher risk of suffering from diabetes and 5.8 times higher risk of suffering from depression when compared with the normal population. People with disabilities face more barriers to accessing health services even though they need more frequent hospital visits (Gudlavalleti et al. 2014). A systematic review concluded that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is high among people with disabilities (Thiagesan et al. 2022). They face various barriers while accessing health services such as lack of disability-friendly transport, communication barriers, inability to access the health facility, and lack of disability-friendly equipment such as beds, chairs, and stretchers (Tesfaye et al. 2021). The intersectionality of age and gender, age-gender-caste, and gender-caste-disability adds to the burden and vulnerability of disability (Sharma and Sivakami 2019). Article 25 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) states that it is the right of persons with disabilities to be provided health services specific to their disabilities from early identification of diseases and prevention of further disabilities. It also emphasizes appropriate measures to ensure that health services are accessible to persons with disabilities (United Nations 2006). The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 in India mentions that all public and private healthcare centers should provide barrier-free access to people with disabilities (The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016). This Act describes only 21 types of disabilities, which is not comprehensive in its scope. Despite these legislations, people with disabilities continue to face various challenges in accessing healthcare services. This is a major ethical concern. In this article, we will frame the barriers in healthcare service provision to persons with disabilities and propose an ethical framework to address these barriers.

Framing the Barriers in Providing Healthcare Services to Persons with Disabilities

Barriers in Access to Healthcare

Physical and Financial Barriers

Distance is one of the key factors that limit access to healthcare which in turn affects healthcare utilization (Kumar et al. 2014). In the South India Disability Evidence (SIDE) study, it was found that the cost of transportation is a barrier to accessing healthcare wherein 13% of people with disabilities reported it to be a barrier (Gudlavalleti et al. 2014). A study conducted in Mumbai among people with disabilities reported that the public transportation services are not well equipped for wheelchairs and the design of the bus itself is not disabled-friendly (Gilder 2020). The local railway stations in Mumbai “fails accessibility tests” and the duration of train halt is minimal at 30 s which does not provide enough time to get in or get out. Even the taxi services such as Ola and Uber do not have a mechanism to handle a wheelchair. Some states such as Delhi and Goa have started to acquire wheelchair-friendly busses (Gilder 2020). A newspaper article reported that, despite free travel for people with disabilities, many of them are unable to utilize the bus services due to the lack of ramps and higher steps height in the government busses in Chennai (Srikanth and Poorvaja 2021). The poor accessibility of public transportation pushes persons with disabilities to opt for private transport to access healthcare services. This leads to out of pocket indirect costs, which greatly hinder access to healthcare services. Another important barrier to accessing healthcare among people with disabilities is the higher out-of-pocket expenditure (OoPE) due to the higher cost of services (Tesfaye et al. 2021). Disability is positively associated with higher OoPE (Sriram and Khan 2020). Public health facilities are not inclusive and therefore persons with disabilities are forced to seek private care. This in turn leads to higher OoPE. People with disabilities face catastrophic health expenditures and more than half of them cannot afford healthcare (James et al. 2019). Vulnerable groups such as people with disabilities are less likely to be enrolled in a health insurance program (Hees et al. 2019). This further pushes them into catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment.

Non-inclusive Health Facilities

As per the guidelines from Indian Public Health Standards 2022, all the HWCs should have a disabled-friendly environment and comprehensive health services which includes prevention and rehabilitation services (MoHFW 2022a). An audit of physical access to PHCs for people with disabilities in Karnataka reported that despite having ramps and pathways to access the PHCs, most of the facilities did not have disabled-friendly toilets, proper examination tables, weighing scales, and doors that are accessible to people with disabilities (Nischith et al. 2018). Due to affordability issues, usage of supportive aids is very minimal among people with disabilities (Kalaiselvi et al. 2017). This situation is not only true for public health facilities, but also for private facilities, thus making healthcare services inaccessible even for those who have the ability to pay.

Provider-related Barriers

In many private and public health facilities, healthcare providers are insensitive to the needs of persons with disabilities. Some of them discriminate against persons with disabilities and treat them disrespectfully, this driving them away from seeking healthcare services. Healthcare providers often lack knowledge of the health needs of people with disabilities and have inadequate training on disability (WHO 2021).

As discussed above, all these barriers impede the inclusion of people with disability in the health policy and healthcare services. This leads to a gross injustice to this vulnerable community.

Lack of Disability-friendly Health Policies

Authenticity of Data

The world report on disability published by World Health Organization reported a prevalence of 24.9% (WHO 2011) in India which is higher than the national data. This incongruence in disability data is a matter of concern. The 2011 census had limitations such as underestimation of milder impairments, usage of narrow medical definitions, lack of medical examinations, and dependence on the perception of disability of the enumerator as well as the respondent. Because of the stigma associated with disability, there is a possibility of under-reporting as well (Saikia et al. 2011). A study conducted in India using different data sources concluded that the estimates from these sources are much lower than the population level estimates in comparison with the Global Burden of Diseases Report and that India should seriously work to improve the reliability and validity of the disability estimates (Dandona et al. 2019). Lack of proper estimation through quality data can lead to inadequate planning which could directly impact the health needs of people with disabilities. The estimation of various diseases will also be affected due to the lack of proper data. Since there is a lack of data, we cannot devise tailor-made interventions for people with disabilities. This directly affects the health status and health needs of people with disabilities.

While there are health programs and health policies exclusively for chronic diseases such as the National Program for Prevention & Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases & Stroke (NPCDCS), they do not focus on people with disabilities as a special vulnerable group (Directorate General of Health Services, MoHFW 2013). Public health programs are driven by political mandate and public health data might not always include feedback from patients (Pappaioanou et al. 2003). Even the recently launched programs like the Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) program under Ayushman Bharat have not addressed the specific health and wellness needs of people with disabilities (MoHFW 2022b). Similarly the National TB Elimination Program or the Reproductive and Child Health Programs do not focus on disability as a key vulnerability.

There is a marginal increase in the budget allocation for the health sector in India. India has allocated 0.0084% of its GDP for people with disabilities for the financial year 2022–2023 in the budget which has declined from 0.0097% in the total allocations made in the 2020–2021 budget. Despite the hard times during COVID-19 for people with disabilities, their budget allocation has almost remained stagnant. Also, the social welfare schemes for this group of people are extended to those living below the poverty line and exclude the maximum number of people with disability. Goods and Services Tax (GST) of 5 to 18% is being levied for most disability assistive devices which further imposes financial hardship for people with disability (Mathur 2022). On the notes on demands for grants from the Union budget for the department of health and family welfare under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, there is no mention of any of the programs wherein the budget is directly allocated for people with disabilities or any special programs for them (MoHFW 2022c). Poor budget allocation leads to poor implementation and poor utilization which will negatively affect the healthcare needs of this vulnerable group.

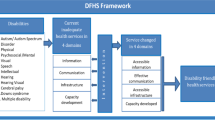

Ethical Framework for Delivering Healthcare for Persons with Disabilities

To provide better, inclusive, and ethical healthcare for people with disabilities, a comprehensive ethical framework is required. We propose such an ethical framework as given in Table 1. This ethical framework is developed from the basic ethical principles of justice, fairness, trust, solidarity, stewardship, and responsiveness, all of which underpin the delivery of healthcare services to the population (Schröder-Bäck et al. 2014; National Council on Disability 2022). The framework addresses the ethical challenges and barriers in delivery of healthcare services to persons with disabilities as framed above, and proposes strategic solutions grounded in various ethical principles.

Stewardship for Protecting the Health Rights of Persons with Disability

Stewardship for protecting the rights of persons with disabilities should be included right from the time of health professions education to all those who are involved in the provision of healthcare directly or indirectly. This will create an enabling environment within the health system wherein there shall not be stigma or discrimination against people with disabilities within the healthcare system and among the healthcare providers. In the health system, stewardship ensures that all components of the health system work well and together for better healthcare delivery for people with disabilities.

A study conducted in Iran regarding health system barriers to rehabilitation services for people with disabilities identified that defect of stewardship which includes factors such as improper policies, limited involvement of rehabilitation specialists, and lack of coordination is one of the key barriers to access to the service (Abdi et al. 2015). Any health system reform would fall short of expected results if stewardship is not included as a key component (Abdi et al. 2015). It should provide a clear vision and outcome-oriented policies for this vulnerable group of people with disabilities by providing transparency and by preventing misuse of the resources (Duran et al. 2014).

Trust in Health System among Persons with Disabilities

Trust plays a vital role in public health (Yadav 2021). Owing to stewardship failures, there is mistrust in the Indian medical system. Trust is a crucial component in public health as it means bridging helplessness, doubt, and randomness in healthcare provision. There is a need for a trust-based approach rather than a control-based approach (Kane and Calnan 2017). Mistrust leads to poor interaction with the health system, poor medication adherence, undesirable behaviors and attitudes, and less satisfaction thus leading to increased medical expenditure and inefficient resource allocation (Krot and Rudawska 2021). Trust is instrumental as it leads to better compliance, openness, and a self-reported feel-good factor (Gopichandran 2016). Thus, the health systems should strive to develop and improve trust among people with disabilities wherein this vulnerable group does not feel left out of the health system (Vries McClintock et al. 2016). Gaining their trust will be the entry point to reducing most of the health system-level barriers to providing better healthcare for people with disabilities and improving their quality of life. By enhancing stewardship, we can build trust within the health system and between the health system and people with disabilities.

Justice

The principle of justice requires that healthcare services are provided proportionate to the needs of the persons. Persons with disabilities have greater need for healthcare services, but currently face great barriers and challenges in accessing them (Singh 2020). The principle of justice will demand that they receive easy and liberal access to healthcare services. Table 1 uses these core ethical principles to develop an ethical framework for addressing the barriers to healthcare access to persons with disabilities.

Sugamya Bharat Abhiyan (Accessible India Campaign) was launched by the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities of the Government of India on 3 December 2015. The goal of this campaign is to make the built environment, transportation sector and the information, communication technology accessible to persons with disabilities. Specific targets have been set under this campaign and if implemented efficiently, it will go a long way in addressing the barriers of providing healthcare to persons with disabilities (Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, MoSJE 2021).

An audit of government websites conducted in 2017 revealed that only 36% of them were made accessible. An audit of accessibility of all domestic airports in 2018 revealed that only 55 of the 104 airports were completely accessible. Only 3.6% of public busses were wheelchair accessible as of March 2018. But about 20% had been made accessible in some form or the other but without wheelchair accessibility. Given these findings, the government of India set a fresh timeline of achieving all the targets by March 2020 (Sharma 2019). The rate of achievement of the Accessible India targets has been slow and it remains to be seen how much has been achieved since 2020. Therefore, much of the ethical issues related to access to healthcare to persons with disabilities remain unaddressed. There is a need to urgently take stock of the achievement of these targets through a rigorous audit and take steps to speed up the process.

Conclusion

This framework attempts to address the ethical burden and challenges in healthcare provision to people with disabilities. By enhancing and improving stewardship in public health programs, proportional allocation of resources can be ensured. This will lead to improved trust of the people with disabilities in the health system and ensures equitable healthcare provision. By doing so, we can ensure justice in healthcare for people with disability.

Data Availability

All analyses were based on publicly available data and are appropriately cited.

References

Abdi, K., M. Arab, A. Rashidian, M. Kamali, H.R. Khankeh, and F.K. Farahani. 2015. Exploring barriers of the health system to rehabilitation services for people with disabilities in Iran: A qualitative study. Electronic Physician 7 (7): 1476–1485. https://doi.org/10.19082/1476.

Balarajan, Y., S. Selvaraj, and S.V. Subramanian. 2011. Healthcare and equity in India. Lancet 377 (9764): 505–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6.

Dandona, R., A. Pandey, S. George, G.A. Kumar, and L. Dandona. 2019. India’s disability estimates: limitations and way forward. PLoS One 14 (9): e0222159. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222159.

de Vries McClintock, H.F., F.K. Barg, S.P. Katz, M.G. Stineman, A. Krueger, P.M. Colletti, T. Boellstorff, and H.R. Bogner. 2016. Healthcare experiences and perceptions among people with and without disabilities. Disability and Health Journal 9 (1): 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.08.007.

Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, MoSJE. 2021. Accessible India campaign. Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. https://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/content/page/accessible-india-campaign.php. Accessed 18 January 2023.

Directorate General of Health Services, MoHFW. 2013. National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases & Stroke (NPCDCS) operational guidelines (revised: 2013–17). Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/OperationalGuidelinesofNPCDCS/28Revised-2013-17/29.pdf.

Duran, A., J. Kutzin, and N. Menabde. 2014. Universal coverage challenges require health system approaches; the case of India. Health Policy 114 (2–3): 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.11.009.

Gilder, Ava. 2020. Public transport in Mumbai: challenges faced by the disabled community. Confluence: Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies IV. https://cjids.in/volume-iv-2020/public-transport-in-mumbai-challenges-faced-by-the-disabled-community-2/public-transport-in-mumbai-challenges-faced-by-the-disabled-community/. Accessed 17 Jan 2023.

Gopichandran, Vijayaprasad. 2016. Trust in healthcare: an evolving concept. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 10(2): 79. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2013.027.

Gudlavalleti, M.V.S., N. John, K. Allagh, J. Sagar, S. Kamalakannan, S.S. Ramachandra, South India Disability Evidence Study Group. 2014. Access to healthcare and employment status of people with disabilities in South India, the SIDE (South India Disability Evidence) study. BMC Public Health 14: 1125. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1125.

Gupta, P., K. Mani, S.K. Rai, B. Nongkynrih, and S.K. Gupta. 2014. Functional disability among elderly persons in a rural area of Haryana. Indian Journal of Public Health 58 (1): 11–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-557X.128155.

James, J.W., C. Basavarajappa, T. Sivakumar, R. Banerjee, and J. Thirthalli. 2019. Swavlamban Health Insurance scheme for persons with disabilities: An experiential account. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 61 (4): 369–375. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_77_19.

Kalaiselvi, S., N. Ramachandran, D. Nair, and C. Palanivel. 2017. Prevalence of self-reported morbidities, functional disabilities and access to supportive aids among the elderly of urban Puducherry. West Indian Medical Journal 66: 191–196. https://doi.org/10.7727/wimj.2015.313.

Kane, S., and M. Calnan. 2017. Erosion of trust in the medical profession in India: Time for doctors to act. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 6 (1): 5–8. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2016.143.

Krot, K., and I. Rudawska. 2021. How public trust in healthcare can shape patient overconsumption in health systems? The missing links. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083860.

Kumar, S.G., G. Roy, and S.S. Kar. 2012. Disability and rehabilitation services in India: Issues and challenges. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 1 (1): 69–73. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.94458.

Kumar, S., E.A. Dansereau, and C.J.L. Murray. 2014. Does distance matter for institutional delivery in rural India? Applied Economics 46 (33): 4091–4103. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2014.950836.

Mathur, Barkha. 2022. Able 2.0: How inclusive of persons with disabilities is the union budget 2022–23. NDTV, 28 February 2022. https://swachhindia.ndtv.com/able-2-0-how-inclusive-of-persons-with-disabilities-is-the-union-budget-2022-23-66879/. Accessed 18 Jan 2023.

MoHFW. 2022a. Indian public health standards: Health and wellness centre - primary health centre. National health mission, ministry of health and family welfare, Government of India. Available from: http://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/guidelines/iphs/iphs-revised-guidlines-2022/03_PHC_IPHS_Guidelines-2022.pdf.

MoHFW. 2022b. Ayushman Bharat - health and wellness centre. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. https://ab-hwc.nhp.gov.in/. Accessed 18 Jan 2023.

MoHFW. 2022c. Notes on demands for grants, demand No. 46. Ministry of health and family welfare, government of India. https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/eb/sbe46.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2023.

National Council on Disability. 2022. Health equity framework for people with disabilities. Policy Framework. Government of United States of America. https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Health_Equity_Framework.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2023.

Nischith, K.R., M. Bhargava, and K.M. Akshaya. 2018. Physical accessibility audit of primary health centers for people with disabilities: an on-site assessment from Dakshina Kannada district in Southern India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 7 (6): 1300–1303. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_177_18.

Pappaioanou, M., M. Malison, K. Wilkins, B. Otto, R.A. Goodman, R.E. Churchill, M. White, and S.B. Thacker. 2003. Strengthening capacity in developing countries for evidence-based public health: The data for decision-making project. Social Science and Medicine 57 (10): 1925–1937. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00058-3.

Saikia, N., J.K. Bora, and D. Jasilionis. 2016. Shkolnikov VM. 2017. Disability divides in India: evidence from the 2011 census. PLoS One 11 (8): e0159809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159809.

Schröder-Bäck, P., P. Duncan, W. Sherlaw, C. Brall, and K. Czabanowska. 2014. Teaching seven principles for public health ethics: Towards a curriculum for a short course on ethics in public health programmes. BMC Medical Ethics 15: 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-15-73.

Senjam, S.S., and A. Singh. 2020. Addressing the health needs of people with disabilities in India. Indian Journal of Public Health 64 (1): 79–82. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_27_19.

Sharma, Nidhi. 2019. Fresh deadline for accessible India drive set to March 2020, targets missed by 1 to 3 years. Economic Times, 28 December 2019. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/fresh-deadline-for-accessible-india-drive-set-to-march-2020-targets-missed-by-1-to-3-yrs/articleshow/73003269.cms?from=mdr. Accessed 18 Jan 2023

Sharma, S., and M. Sivakami. 2019. Sexual and reproductive health concerns of persons with disability in India: An issue of deep-rooted silence. Journal of Biosocial Science 51 (2): 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932018000081.

Singh, S. 2020. Disability ethics in the coronavirus crisis. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 9 (5): 2167–2171. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_588_20.

Srikanth, R., and S. Poorvaja. 2021. Accessibility in public transport still elusive for disabled persons. The Hindu. 1 September 2021. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/chennai/accessibility-in-public-transport-still-elusive-for-disabled-persons/article36215997.ece.

Sriram, S., and M.M. Khan. 2020. Effect of health insurance program for the poor on out-of-pocket inpatient care cost in India: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Services Research 20: 839. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05692-7.

Tesfaye, T., E.M. Woldesemayat, N. Chea, and D. Wachamo. 2021. Accessing healthcare services for people with physical disabilities in Hawassa City Administration, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 24 (14): 3993–4002. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S317849.

The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act. 2016. Ministry of social justice & empowerment, Government of India. https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A2016-49_1.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2023.

Thiagesan, R., V. Gopichandran, S. Subramaniam, H. Soundari, and K. Kosalram. 2022. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes among persons with disabilities in the South-East Asian region: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Medical Issues 20: 161–167. https://doi.org/10.4103/cmi.cmi_27_22.

United Nations. 2006. Article 25 – Health, United Nations Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). New York: United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-25-health.html.

van Hees, S., T. O’Fallon, M. Hofker, M. Dekker, S. Polack, L.M. Banks, and E. Spaan. 2019. Leaving no one behind? Social inclusion of health insurance in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. International Journal for Equity in Health 18 (1): 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1040-0.

WHO. 2011. World report on disability. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564182. Accessed 18 January 2023.

WHO. 2021. Factsheet: Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health.

Yadav J. 2021. Public trust in healthcare systems in India. BMJ Open 11(Suppl 1): A13–A14. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-QHRN.37.

Zuurmond, M., I. Mactaggart, N. Kannuri, G. Murthy, J.E. Oye, and S. Polack. 2019. Barriers and facilitators to accessing health services: A qualitative study amongst people with disabilities in Cameroon and India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (7): 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071126.

Acknowledgements

This work was developed during a Public Health Ethics WriteShop organized by the Rural Women’s Social Education Centre, Chengalpet District, Tamil Nadu, as part of a research project on public health ethics funded by the Thakur Foundation. We would like to acknowledge Prof. Olinda Timms, who provided guidance and mentorship in writing this manuscript.

Funding

The lead author RT received a fellowship for this work as part of the Public Health WriteShop in which this work was developed. This fellowship was offered by Rural Women’s Social Education Centre, Chengalpet District, Tamil Nadu, through a grant that they received from Thakur Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RT and VG conceptualized the paper. RT prepared the first draft. VG edited it extensively for content. HS and KB participated in discussions on the manuscript and subsequently reviewed the content. All four authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This is a conceptual paper and did not involve human participant research. Therefore, ethics approval and consent to participate are not applicable.

Consent for Publication

We have not used any identifiable patient material or any copyrighted material from other publications. Therefore, consent for publication is not applicable.

Competing Interests

The author VG is the principal investigator of a research project on public health ethics funded by the Thakur Foundation. A Public Health Ethics WriteShop was organized as part of this project in which a modest writing fellowship was provided to young scholars from across the country to develop papers on public health ethics. RT was recipient of this fellowship. Remaining authors do not have any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Thiagesan, R., Gopichandran, V. & Soundari, H. Ethical Framework to Address Barriers to Healthcare for People with Disabilities in India. ABR 15, 307–317 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-023-00239-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-023-00239-4