Abstract

The objective of this article is to gain an in-depth understanding of the eating lives of low-income single mothers in Japan. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine low-income single mothers living in the three largest urban areas (Tokyo, Hanshin [Osaka and Kobe] and Nagoya) in Japan. Framed by the capability approach and sociology of food, their dietary norms and practices, as well as underlying factors that impact the norm-practice gap were analysed across nine dimensions: meal frequency, place of eating, meal timing, duration, persons to eat with, procurement method, food quality, meal content and pleasure of eating. These mothers were deprived of various types of capabilities, extending not only from the quantity and nutritional aspects of food, but also to spatial, temporal, qualitative and affective aspects. Aside from financial constraints, eight other factors (time, maternal health, parenting difficulties, children’s tastes, gendered norms, cooking abilities, food aid and local food environment) were identified as influencing their capabilities to eat well. The findings challenge the view that food poverty is the deprivation of economic resources required to ensure a sufficient amount of food. Social interventions that go beyond monetary aid and food provision need to be proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food Insecurity and the Capability Approach

After a series of global crises, food insecurity has become an increasingly important social issue. Food security is defined as ‘a situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that merits their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ (FAO 2009). The concept of food insecurity has been expanded to refer not only to the unavailability of food but also to access, utilisation and stability (Peng and Berry 2019). It is generally understood in the food insecurity literature (Barret 2010) that this change in focus from commodities (‘availability’) to capabilities (‘access’ and ‘utilisation’) was enabled by the adoption of Amartya Sen’s capability approach (CA). The CA was developed to overcome the deficiencies of traditional ethical theories, notably utilitarianism and the Rawlsian primary goods approach. It treats the capability or freedom of an individual to achieve well-being as an informational basis for ethical evaluation (Sen 1980). The CA has increasingly been employed for the analysis of contemporary food issues (Hart 2016; Hart and Page 2020; Ueda 2021, 2022a, 2022b; Visser and Haisma 2021), but our study is one of the first attempts to examine food insecurity in developed countries.

Various measurements have been developed to operationalise food insecurity (e.g., Carlson et al. 1999; Cafiero et al. 2018), but they are not free of methodological problems. In reviewing the literature on food insecurity in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Ashby et al. (2016) noted that most instruments measure ‘the financial constraints associated with acquiring sufficient amounts of food’ and argued that, by failing to assess its multidimensionality of food insecurity, they might ‘underestimate the true prevalence of food insecurity’. The adoption of such a narrow perspective, which focuses on economic constraints and food availability, is due not only to data availability but also to the interpretation of the CA as a supporting theory.

From a capability perspective, it can be argued that current food insecurity measurement instruments are characterised by two types of reductionism. The first is related to the totality of one’s dietary life. Although the primary issue in Sen’s (1982) analysis of famine in India was access to sufficient food, his following works on CA (Drèze and Sen 1989; Sen 1992) include a much wider range of food-related activities in its basis of evaluation. Second, poverty, if defined as deprivation of capabilities, results from various factors, not exclusively from low income. Focusing solely on financial constraints is insufficient if one wishes to grasp the true nature and complexity of food insecurity.

The argument that multiple factors cause food insecurity seems to be supported by the international literature on dietary lives in households with low socio-economic status (SES). In their literature review, van der Heijden et al. (2021) helpfully identified several factors that influence healthy eating among the low-SES populations of Western countries. These factors range from time and monetary constraints (e.g., Dibsdall et al. 2002; O'Neill et al. 2004; Inglis and Crawford 2005; Lucan et al. 2012; Fielding-Singh 2017) to various interpersonal factors, including the food preferences or tastes of others (e.g., Inglis and Crawford 2005; Teuscher et al. 2015; Fielding-Singh 2017), the difficulty of regulating children’s food intakes (e.g., Backett-Milburn et al. 2006; Hardcastle and Blake 2016; Herman et al. 2012), and the gendered ideal of a ‘good mother’ (e.g., Eikenberry and Smith 2004; Lucan et al. 2012; Fielding-Singh 2017). Studies on low-income mothers have also pointed to a number of personal factors that do not conduce to healthy eating, such as lack of dietary information, poor cooking ability, and maternal health (e.g., Dibsdall et al. 2002; Agrawal et al. 2018). Other recent studies on low-income communities place a stronger emphasis on the quality of local food environments (Gravina et al. 2020; Rivera-Navaro et al. 2021). These factors are relevant, to varying degrees, to both low-SES groups and to the general population (e.g., Lappalainen et al. 1998; Munt et al. 2017; Zorbas et al. 2018).

All of these studies have contributed to highlighting the presence of multiple factors that influence dietary well-being. However, none of the concerned scholars have presented an explicit and critical discussion that reconceptualises food insecurity. This gap is plugged in this article, which takes single mothers in Japan as its main example.

Food Poverty in Japan

The Japanese experience demonstrates how a limited interpretation of food insecurity can be problematic. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (2022) index, which focuses on ‘the financial constraints associated with acquiring sufficient amounts of food’, only 3.4% of the Japanese population suffers from food insecurity. However, the poverty rate in Japan is 15.7%, the highest among the developed countries (OECD 2021). As awareness on poverty has increased since the 2000s, various food-related problems (malnutrition, lack of opportunities for eating at home or dining out, skipping meals and such like) have been subsumed under the broad concept of ‘food poverty’ (shoku no hinkon), which, although poorly defined, reflects Japanese realities accurately. Therefore, we also employ the concept of ‘food poverty’ in the present study. To clarify, food poverty is similar to food insecurity as originally defined (FAO 2009). Both concepts refer to the totality of the dietary lives of individuals and to the multiple factors that influence them. However, we are compelled to differentiate between these terms here because the operational use of ‘food insecurity’ is far from ideal. We also define later the food poverty concept analytically from a CA perspective.

In Japan, single mothers are the most high-risk social group in Japan, with a poverty rate of 51.4% (JILPT 2019); once more, this is the highest poverty rate in the developed countries (OECD 2021). The delayed socio-political restructuring of the ‘post-war family regime’ in Japan may provide an explanation of the high poverty rate in single mothers (Ochiai 2019). Under that regime, the model of a modern family which revolves around a couple and their children is treated as a standard. Other families, notably single parents, are marginalised in the provision of public assistance. It is also under the influence of this post-war family regime that the gendered norm of the family’s dining table as a locus of love and as a responsibility for mothers has been promoted extensively.

Beyond single mothers, poverty among children (14.0%) and the elderly (25.8%) also deserves attention (OECD 2021). Child poverty is the obverse of poverty among parents and, thus, among single mothers (Abe 2008). At the same time, single mothers also face the highest risk of poverty in advanced age – at present, more than 40% of the elderly poor are women who live in one-person households (Fujimori 2018). Therefore, focusing in this study on single mothers can eventually contribute to understand this increasing phenomenon as well as to alleviate poverty among other marginalised groups.

Despite its significant poverty rate, Japanese scholars only began to take an interest in (food) poverty at a late stage. Townsend’s (1979) theory of relative poverty granted food a new epistemological status as an integral part of well-being. According to that theory, various food-related activities, such as eating breakfast every day and drinking tea with friends occasionally, become legitimate objects of evaluation. However, this paradigm of relative deprivation has only been applied to empirical studies in Japan since the 2000s (e.g., Abe 2006). Moreover, the main concern has been with well-being as a whole, including education, health and social life; only a few indicators of food-related activities are employed.

Nutritionists and economists in Japan have also studied food poverty since the 2010s. A research project on the socio-economic factors that are associated with healthy eating that the Japanese Ministry of Health initiated in 2012 generated important evidence of the dietary realities of low-income households. The individuals in question consume fewer fruits and vegetables (Nishi et al. 2017) and are less conscious of the health effects and the quality of food (Hayashi et al. 2015), Furthermore, children from low-income households have less healthy diets than children from middle- and high-income families (Hazano et al. 2017).

Economists have gathered evidence, particularly on single mothers. Using national statistics, Tani and Kusakari (2017) reported excessively low food expenditure (the equivalent of 7.6 EUR per day) among single mothers with low incomes comparing to 13.5 EUR of a non-poor household food expenditure. Ishida et al. (2017) combined a series of national statistics and revealed that single mothers lead less healthy eating lives and provide less food education to their children, with time constraints and upbringing identified as prominent underlying factors. Most recently, Matsuda et al. (2020) conducted in-depth interviews with eight single mothers, two of whom were under the poverty line, and categorised their eating practices on numerous dimensions. However, qualitative studies on this population are much scarcer in Japan than in Western countries.

Research Objectives

We conducted a qualitative analysis in order to expand the present understanding of the dietary lives of Japanese single mothers on low incomes, with a particular focus on the multidimensional aspects of their eating realities and on multiple factors (not limited to monetary constraints). The aim is to overcome the limitations of past studies on food insecurity or food poverty.

Methods

Ethical and Sociological Framework: Application to Semi-Structured Interviews.

The theoretical framework is based on a combination of the CA and the sociology of food. This combined approach has previously been applied to examinations of the total range of eating well among the Japanese population, and it entailed the distribution of questionnaire surveys (Ueda 2022a, 2022b). The questionnaires were adapted for the purposes of the semi-structured interviews that are presented in this study. In the literature on CA-based food studies (e.g., Hart 2016; Hart and Page 2020; Visser and Haisma 2021), Ueda (2021) examined the theoretical affinity of CA and food issues, proposing the following analytical concepts:

-

(1)

‘Well-eating’ refers to the quality of a person’s eating life (food-specific well-being). Well-eating is composed of a set of functionings to eat well.

-

(2)

‘Functionings to eat well’ refers to various beings and doings that the person has reason to value. The functionings extend from elementary ones (e.g., being nutritiously satisfied) to complex ones (e.g., being able to eat out occasionally).

-

(3)

‘Capability to eat well’ is the freedom to convert limited commodities (mainly foodstuffs and household income) into the achievement of functionings to eat well.

-

(4)

‘Conversion factors’ refer to various personal (e.g., nutritional knowledge) and social (e.g., public health facility) factors that inhibit or facilitate the achievement of functionings to eat well.

Followingly, we highlight some important features of this framework. First, concerning the first and second concepts listed above, the totality or multidimensionality of a person’s well-eating can be analytically understood as a set of functionings to eat well. Following a previous study (Ueda 2022b),22 in this study theoretical insights were also taken from the sociology of food to identify such functionings. Here, we refer to the sociology of food that emerged in the 1980s in France as an approach to analysing eating as a total (bio-psycho-social) act (Poulain 2017). In light of a critical reflection on sociological and anthropological works on food and its empirical application (Poulain 2002a, 2002b; Ueda and Poulain 2021), the following nine dimensions are presented to capture the totality of contemporary eating: (1) meal frequency, (2) place of eating, (3) timing of meals, (4) meal duration, (5) persons to eat with, (6) procurement, (7) quality of the food, (8) meal content and (9) pleasure of eating.

Second, regarding the third notion, the capability to eat well is a freedom-type concept: how well the person’s valued functionings (norms) can be achieved in actual eating practices. The norm-practice gap refers to a situation in which the person desires to achieve something but fails to do so for some reason. It can thus serve as a barometer for the capability to eat well (Ueda 2022b). Here, ‘norms’ are not social norms, which are externally imposed on individuals, but rather their (diversely) internalised values and desires (Moscovici 2001; Ueda 2022b).

Third, for what concerns the fourth concept, various conversion factors constitute the diversity of situations in which each person finds themselves (which had not been addressed in traditional ethical approaches, including utilitarianism and Rawlsian primary goods approach). Elucidating the diversity of conversion factors can thus relativise the view that financial constraints determine the person’s well-eating.

Therefore, in the semi-structured interviews, each evaluative dimension was explored in terms of norms, practices and conversion (inhibiting) factors (Table 1). To ensure the accuracy of the interview data, the real practices of the participants’ most recent working days (such as ‘yesterday’ and ‘this week’) were assessed. If these practices deviated greatly from their routines (for irregular reasons, such as catching a cold), the most recent habitual practices were analysed instead to retain data representativeness. Prior to the interviews, all questions and their relevance to single mothers were validated by the partnered non-profit organisations.

Supplementary Data: Life Conditions and Nutritional Status

As proposed in a previous qualitative study on single mothers (Matsuda et al. 2020), the interviews also included questions about overall life conditions, such as time constraints, mental health and upbringing, as well as socio-demographic status. Two questions about the ‘professions of their parents’ and the ‘perceived standard of living during their childhood (aged about 15)’ were newly added to obtain possible insights regarding the generational chain of (food) poverty.

In addition, the brief-type self-administered diet history questionnaire (BDHQ) was filled in right after the interviews to measure objective nutritional status. The BDHQ is one of the most widely used tools in Japanese nutritional policymaking. The participants reported their food intake frequency during the most recent one-month period by completing the questionnaire, which made it possible to quantitatively measure their nutritional status with assured methodological validity (Sasaki et al. 1998). Among various outputs from the BDHQ, the number of nutrients (a total of 14 items, such as calcium, iron, vitamin C, etc.) that greatly deviate from national standard amounts and are thus considered ‘necessary for dietary intervention’ were used as a representative indicator of nutritional status in this study.

Data Collection

The participants were recruited as part of the Eating Life of Single Mothers (ELSM) research project. In partnership with three NPOs in the social aid sector, the aim of the project was to gain a holistic understanding of single mothers’ eating lives and to create evidence for the development of effective social interventions. The ELSM project was a qualitative survey focused primarily on eating lives, with the largest ever sample size in Japan, and involving in-depth interviews with 53 single mothers. Eligibility criteria for the interviews were that the participant had to be a single mother living together with at least one child under the age of 15 in one of the three largest urban areas in the country (Tokyo, Hanshin [Osaka and Kobe] and Nagoya). The mothers were recruited by the partnered NPOs via mailing lists and websites. To maximise the sample size, all the applicants who satisfied the eligibility criteria were selected regardless of their socio-demographic status. In Japan, there are two commonly used criteria for determining income-based poverty: the OECD’s threshold (i.e., below half the median income of the total population) and the one for identifying eligible welfare recipients (i.e., below minimum living expenses, the amounts of which vary according to region). So far, the prefectural data is available for only the latter (Tomura 2016), and was thus used for this study.

Of the 53 single mothers, nine (17%) were identified as ‘poor’ based on their disposable personal incomes according to each prefectural criterion on minimum living expenses. These low-income participants were selected as the target of analysis for this article. This sample size fits within the valid range (6–60) of interviews for general social research (Sobal 2001). Although maximum efforts were made to increase the sample size, there were some obstacles for doing so: (i) the difficult-to-reach nature of the targeted population; (ii) the depth and scope extensiveness (Sobal 2001) of the interviews (40 questions plus the BDHQ); and (iii) the unavailability of food-specific official aid programmes for the low-income population in contemporary Japan (the recipients of which are often the major interviewees in food insecurity studies in other advanced countries). Despite this sample size, data saturation was attained to a certain extent (Sobal 2001) by identifying common eating patterns (as detailed below). Although caution is needed when generalising the findings, the sample size, which is currently the largest in qualitative studies on the same group, can be regarded as sufficient, because of its data saturation, to highlight the complexity of the eating lives of the low-income single mothers.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in private offices of the NPOs or universities, which ensured the mothers’ privacy, from August to November 2021 (after all the COVID-19-related restrictions had been lifted). All the interviews (two to three hours each) were conducted by two members of the ELSM project: a sociologist of food as main interviewer and a professional from the responsible NPO for familiarising the mother with the procedure and ensuring that she was relaxed during the interview. Prior to the interviews, the mothers were informed of their objective and content, and, if they agreed to participate, they filled in a letter of informed consent. The mothers were offered compensation (about 70 EUR cash) for the time and expertise they provided. This survey protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Nagoya University (ID: 2021–1).

Participant Profiles

The socio-demographic profiles of the nine participants are indicated in Table 2. Some profile characteristics need to be mentioned prior to the in-depth analysis. Note that since no national statistics are available specifically on low-income single mothers, the most recent statistics on single mothers (MHLW 2016) are referred to in order to infer the sample characteristics. First, the participants were aged 35 and above, which is older than the national average (33.8) of single mothers. The majority had children over elementary-school age; thus, it was difficult to identify unique factors related to food parenting for pre-schoolers in this study.

The second feature concerns SES characteristics. Although all nine mothers were below each region’s poverty line, they can be further divided into two subgroups: moderate poverty (1.5–1.6 million yen per year, equivalent to about 10,000–11,000 EUR) and severe poverty (0.7–0.9 million yen, equivalent to about 5,000–6,000 EUR). In terms of education, four mothers (44%) were high school graduates, which is almost the same as the national average for single mothers (45%). Thus, their educational level can be considered relatively high among single mothers with low income, if premised on the notion that those with lower incomes are generally less educated. In terms of profession, six mothers (67%) were non-regular employees, which is higher than the national average for single mothers (48%). Nonetheless, it was difficult to estimate their social positioning among poor single mothers on the basis of this information alone. In sum, when consideration is given only to income and education levels, the nine mothers can be regarded as having relatively high SES among the low-income single mother population, although caution is needed for the three mothers experiencing severe poverty conditions. This sample deviation is due to the recruitment method, in which only mothers with some level of social capital (i.e., direct or indirect relationships with the NPOs) could be contacted. It is important to bear in mind that these nine mothers were from the social group living in relatively moderate economic poverty and that there are single mothers living in more severe poverty conditions.

Analysis of the Interview Data

The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and interpreted by the responsible two interviewers. Although asked in an open-ended manner, the answers to the questions on living conditions, eating ideals and practices in each dimension were coded based on the corresponding closed questions in previous studies (Matsuda et al. 2020; Ueda 2022b).Footnote 1

It was expected that various inhibiting factors would be reported. Therefore, the coding protocol was developed on the basis of the aforementioned literature on the factors that underlie healthy eating in low-SES families (e.g., van der Hejiden et al. 2021) and in households as a whole (e.g., Lappalainen et al. 1998). The following eight relevant factors were identified: financial constraints, time constraints, maternal health status, parenting difficulty, the tastes of family members (mainly children), social norms (mainly about motherhood), cooking ability and local food environments. Given that most of the participants in past studies were in receipt of assistance, the ‘food aid’ factor was also added to this set. The nine factors, taken together, function as an organising scheme and eventually enable many of the answers to be sorted into categories. Further modifications and reorganisations are introduced in the discussion section. The categorisation was not as complex as initially expected because the number of factors provided by the respondents for each functioning did not normally exceed two. This coding was performed by the two interviewers separately and the results were then confirmed and discussed by the two to reach a shared interpretation of the data. Again, our coding was driven by pre-defined categories. Therefore, it does not reflect the adoption of an inductive (exploratory) approach.

After the initial analysis, the first results were presented to other researchers (sociologists, economists and nutritionists) at seminars that are convened regularly and at two academic conferences, one on agricultural economics and one on poverty studies, so as to arrive at a ‘trans-positional’ assessment (Sen 1993) that reflects consensus across disciplinary boundaries. This procedure ultimately confirmed the validity and extensiveness of the pre-determined categories of conversion factors but different positional views were integrated to enrich the interpretation of the results.

Results

Overall Living Conditions and Nutritional Status

Five important characteristics were identified in terms of overall living conditions and nutritional status (Table 3). First, according to their self-reports, three mothers (33%) suffered from mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia, depression), eight (89%) were mentally ‘(very) unstable’ and seven (78%) were physically ‘(very) tired’. Second, the children of six mothers (67%) experienced some difficulties, such as development disorder, autism or school refusal. Third, the objective time constraints, which can be calculated from working and commuting hours (Matsuda et al. 2020),Footnote 2 were large for five mothers (56%: negative numbers in Table 3). Three (33%) perceived themselves to be ‘very busy’ or ‘busy’, although their objective time constraints were not large. Fourth, six (67%) were from families of self-employed small-business owners (e.g., hostess bar, carpenter or noodle restaurant owners) and, thus, were likely from humble backgrounds. Another similarity is that eight were from families whose mothers were part-time workers or housewives and could, consequently, dedicate considerable time to preparing family meals. Lastly, their nutritional status was generally not good. Seven (78%) did not meet the required intake amount for two or more nutrients (among calcium, iron, vitamin C, fibre and potassium). Five mothers exceeded the acceptable amount of salt intake according to the national standard (Sasaki et al. 1998).

Norms, Practices and Conversion Factors for Achieving Well-Eating

In light of the objective of this study, which is to elucidate the dietary lives of low-income single mothers in a multidimensional way, the practices and the inhibiting factors that pertain to each evaluative dimension are described below. Information on dietary norms is also provided where necessary so as to clarify the nature of the norm-practice gaps.

Meal frequency

It is useful to distinguish ‘habitual’ skipping (less than three meals per day) from ‘occasional’ skipping (generally three meals a day, but sometimes skipped). The latter was calculated from the questions about place of eating (0 − 7 frequencies per week). In this study, four (44%: #1, #3 − 5) were habitual skippers, whereas seven (78%: #1 − 6, #8) were occasional ones. The total numbers of skippers (both habitual and occasional) were four (44%) for breakfast, three (33%) for lunch and one (11%) for dinner. For the latter, more importance was attached to eating with children and thus tended not to be skipped.

In the case of the three mothers who desired to eat three times a day but did not manage to do so habitually (#1, #3 − 4), one reported time constraints due to work, whereas two identified habitual reasons. As an example of the latter, Mother #4, who used to work as a truck driver, reported the experience of adapting her appetite due to irregular work:

I’m not hungry in the morning and I’m already used to that […] I don’t have a habit of having breakfast and, you know, when driving a truck I lost track of time. Sometimes I left in the morning and at other times I left in the evening.

Place of eating

The original typology of four places of eating was merged into two patterns, depending on who prepared the meals: (i) at home and bento-style (together called ‘Eat-In’) and (ii) taking in and dining out (called ‘Eat-Out’). If the average value among non-meal skippers was taken as a reference here, the Eat-In/Eat-Out frequencies per week were 7/0 times for breakfast, 5.5/1.5 times for lunch and 6.3/0.7 times for dinner (in which calculation, Mother #4’s abnormal case was excluded).

Dinner deserves a closer analysis. As mentioned above, their real frequency of home cooking was 6.3 times per week, which largely deviated from their norms (averaging 3.9 times among the nine mothers). This highlighted the reality that these mothers (#1, #4 − 8) were obliged to cook at home more than they preferred to, primarily for financial reasons. Mother #1, who could not afford to buy meat, wished to eat out, saying, ‘If I can, I hope to eat meat…just once in a month, just in a modest restaurant chain.’

On the other hand, there should not be too few opportunities to cook at home. This dilemma was clearly observed with Mother #2, who received free dinner (bento) six times a week from a neighbourhood NPO, and Mother #4, who ate leftovers for dinner at her workplace (canteen) six times a week. In both cases, the gendered norm that ‘ideal mothers should cook at home’ reinforced their sense of guilt.

I feel very sorry for my children. I also feel guilty that they always eat something in the plastic [bento] box. I wanted to cook myself but… (Mother #2)

I don’t care about myself, but I want my children to eat [home-cooked meals] properly…and I should. But I have to work the night shift, so there’s no way. (Mother #4)

Timing of meals

Taking the average value of non-meal skippers as a reference, the times for starting meals were 7:28 for breakfast, 12:47 for lunch and 19:41 for dinner. The actual timing of their lunches and dinners were about an hour later than their own norms. As emphasised by Mother #7, who struggled with depression, such a delay for dinner would ‘lead to more time constraints for household chores and eat up all my time’, influencing her overall well-being.

Six mothers reported time constraints as a major factor for delaying lunch. However, they identified not only time (#4, #6 − 7) and motivation (#9) constraints, but also their children’s affairs, such as after-school activities (#2 − 3, #8), as inhibiting factors for delaying dinner.

Meal duration

The average values among non-meal skippers were 13 min for breakfast, 22 min for lunch and 26 min for dinner. Their actual meal duration was about 10 − 15 min shorter than their own norms. This shortage also influenced their overall well-being. For example, as Mother #7, who consciously ate her meals slowly to cope with her mental illness, stated, ‘If I can eat slowly, I feel I’m okay and I use time for myself.’

Six mothers reported time constraints due to work or childcare as the major reason for short meal durations. Mother #8, who was the only participant with a pre-schooler, added a troublesome child as a factor relevant to time constraints. Further inhibiting factors were reported, such as a lack of conviviality (#2) and small meal portions (#1 and #8), which relate to other functionings and will be discussed in the relevant sub-sections.

Persons to eat with

There were two solo eaters for breakfast (33% of the non-meal skippers), seven for lunch (78%) and two for dinner (22%). Interestingly, some mothers (four for breakfast and lunch and one for dinner) normalised eating alone, because the practice of eating together with their children was reported to cause a decrease in their well-eating. This ideal was informed by the substantial pressure of balancing work and solo parenting, as expressed by Mother #5, who said, ‘If I spend all the time with my children, I feel phew…I want to stay alone.’ In addition, four mothers (#2, #7 − 9) ate together with their children but could not achieve conviviality due to the children’s affairs (school refusal, development disorder or picky eating) and the resultant difficult child-mother relationships. Other factors influencing the opportunity and the quality of conviviality included the absence of others (#6 − 8) and the obligation of caring for parents and children (#4 − 5, #8).

Place of procurement

Mother #7 habitually used a discount supermarket and the other eight mothers procured their daily foods primarily from national supermarket chains. Among them, seven identified access to ‘cheap’ products, notably discounted foods, as their major motivation for their choice. Most of them also visited other shops for supplementary procurement, two characteristics of which deserve a special mention. The first was the use of drugstores, which are newcomers in the Japanese agri-food industry. Not only the mothers who purchased specific discounted products (#7: eggs, #8: milk) but also those had a heavier reliance for financial advantage (#5: including cut vegetables and pork) were observed. The second feature was the social role of small-scale local retailers who provided indispensable psychological support for the single mothers, who were at risk of social isolation. Examples include the elderly sales clerks at a tofu shop who kept watch over Mother #2’s daughter, who needed mental support due to previous domestic violence, and a middle-aged vegetable shop owner who had daily cheerful communication with Mother #3, who otherwise tended to avoid all social contact due to her mental disease.

Moreover, analysis of the mothers’ norms revealed that the majority (excluding Mother #6, who responded that ‘I don’t know much about other shops so it’s okay for me’) were not satisfied with their current procurement methods. Three discomforts were expressed in relation to the inhibiting factors. First, the quality of food at supermarkets was not good, and professional retailers were favoured as the alternative; however, physical distance from the latter was the major constraint (#2 and #8). Second, discount supermarkets were preferred to normal supermarkets due to their financial advantage, but, again, there was a distance problem (#4). Third, two mothers (#1 and #8) wished to use food delivery in the same manner as ordinary households but abandoned this option due to financial constraints.

Food Quality

Before discussing the quality of the food, the mothers’ responses regarding the ‘experience of being unable to have enough food for financial reasons’ are analysed. All nine mothers reported no such experience. Nevertheless, they shared similar experiences with Mother #1, who said that ‘it’s not that I couldn’t afford enough food, but it’s so often that I gave up what I wanted to buy, like meat, and put something else in the shopping basket’. What was at stake for these single mothers was not the amount but the quality of the food.

In terms of their norms, five mothers (#1, #3–4, #8–9) prioritised price value the most of all the relevant factors. If the price criterion was achieved, they then wished to meet other criteria, such as freshness (#1, #4 and #8) and domestic products (#1, #4, #8–9). However, in practice, only two mothers (#7 and #9) habitually purchased domestic products (meat), whereas none had access to fresh products. Financial constraints were the major inhibiting factor for six mothers, which was partly due to their characteristic purchasing behaviours. For example, one stated that ‘I buy things only in the bargain section of the supermarket’ (#5) and another that ‘I don’t feel interested at all if the sale stickers are not placed on the products’ (#6). This behaviour sometimes led to a significant dilemma, as expressed by Mother #1:

I buy meat and fish only if the sale stickers are placed on them. They are neither rotten nor bad for your stomach, but I’m sure there are more germs. I feel disgusted that these germs are accumulating in my body…

Meal content

Actual meal content is summarised in Table 4. Below, meal content and the logic behind their choices were analysed according to the categorisation based on menu combination (excluding pickled vegetables) found in a previous study (Kudo et al. 2017).

Regarding breakfast, the meal pattern, excluding for the three meal skippers, was ‘staple [rice or bread], soup and dish(es)’ for one mother (#7), ‘staple, fruits and dairy products’ for another (#2) and ‘staple only’ for four (#5 − 6, #8 − 9). These patterns were in accord with the general trend of a high prevalence of the ‘only staple’ pattern (Kudo et al. 2017). Various reasons were reported, including time (#6) and motivation constraints (#5, #8 − 9). In contrast, Mother #6 managed to have breakfast with relatively rich content by preparing miso soup the preceding night and choosing ready-to-make products (e.g., dried fish). Mother #2 also prepared breakfast with care. However, she expressed a feeling of guilt about relying on the free bento provided by some NPO for most dinners.

Lunch patterns were ‘staple, soup and dish(es)’ for two mothers (#3 and #6), ‘staple and dish(es)’ for five (#1, #4, #7 − 9), ‘only staple’ for one (#2) and nothing for one meal skipper (#5). Two reasons were provided for the relatively high prevalence of the ‘staple and dish(es)’ pattern. The first was a low or self-sacrificing attitude towards their own well-eating. Mother #8 stated that ‘because it’s only about me, I don’t want to spend time for lunch’, and Mother #2 commented that ‘I’d rather buy organic vegetables for my children than spend money on my lunch’. Another characteristic attitude was what Mother #8 called ‘lunch a disposal of leftovers’. Indeed, six mothers ate the leftovers of their dinner from the preceding day and the children’s breakfast of the same day for lunch. Mother #6 explained this choice by saying ‘if I want to cut food expenses, the only thing I can do is to reduce food waste’.

The dinner patterns were ‘staple, soup and dish(es)’ for four mothers (#3, #5 − 7), ‘staple and soup’ for two (#1 and #4) and ‘only staple’ for three (#2, #8 − 9). The fact that a high prevalence of the ‘only staple’ pattern was not observed here was partly due to the previously mentioned gendered norm of ‘ideal mothers in the kitchen’, which the participants strongly upheld. All the mothers idealised highly-demanding dinner content (i.e., home-cooked staple, soup and more than two dishes), which enlarged the ideal-practice gap and increased dilemmas about preparing too few dishes (#1, #5 − 7) or unbalanced ones (#8 − 9) in practice. In addition to financial constraints (#2, #6, #8), the children’s picky eating was reported as one of the major inhibiting factors (#1, #6 − 8):

His picky eating is indescribable. I once consulted with the education expert and she said, ‘It’s natural for children of this age,’ but my son is …he actually boycotts everything I prepare. He doesn’t eat rice or have a chat with me at the table. I prepare meals with much effort, so I don’t want to throw them away. I think this is particular to single mothers, because if the fathers were there they would tell the kids off (Mother #7).

The mothers’ cooking abilities also significantly influenced the number of dishes and nutritional balance of their meals. Two mothers (#5 and #9), who both said that they were not good at cooking, had no choice but to rely on ready-made dishes (mostly fried dishes) at supermarkets for the whole or part of their daily dinner. In sharp contrast, the mothers with good cooking skills, such as Mother #3, recalled that ‘because my parents were not at home, I started learning how to cook by myself from very early on, say, the lower grades of elementary school’. Thus, they managed to prepare a staple, soup and three dishes for daily dinner.

Lastly, two aspects of meal content in relation the mothers’ aforementioned nutritional status are worth mentioning. Among the five mothers with poor nutritional status, which is characterised by a deficiency in more than three nutrient items, three (#2, #8 − 9) relied heavily on outsourced meals, such as free bento or ready-made supermarket dishes, whereas the other two (#1 and #6) carried the double burden of relatively large financial constraints and their children’s picky eating. These factors could lead to limiting the diversity of food groups and nutrition. In addition, five mothers had a particular pattern of excessive salt intake due to the consumption of miso soup once or twice a day. Although some did so due to personal preferences, others were obliged to prepare it under conditions unique to them. These included economic choice, waste aversion, children’s pickiness about raw vegetables and the non-demanding cooking skills required to make miso soup.

Pleasure of eating

Five mothers wished to have conviviality in their daily lives, whereas four desired the experience of discovering new and seasonal tastes. However, only three (#2 − 3, #5) were able to achieve conviviality (none for gustative discovery). Time constraints (#4) and the absence of others (#7) prevented them from attaining conviviality, while financial constraints were a major factor in inhibiting gustative pleasure (#6, #8 − 9). This was emphasised by Mother #7, who lamented that ‘I eat only for survival’.

Discussion

Deprived Capabilities in Low-Income Single Mothers

We first overview the different food-related capabilities that the low-income single mothers tended to be deprived of. As a high rate of meal skipping had been indicated in a previous study on Japanese single mothers (Kubo and Ishida 2016), this study also demonstrated the deprivation of their capabilities to ‘have three meals a day’. Although little had been reported about the underlying factors, this study went on to identify the non-monetary reasons for such deprivation and challenged the over-simplified view that they skip meals simply because they do not have enough money.

Problems also existed in both the spatial and temporal aspects of well-eating. When compared with the national average on dinner (Ueda 2022b), their opportunities to eat out were two times less, the starting times were delayed for about 30 min, and the duration was about 5 min shorter. In sum, their capabilities to ‘occasionally outsource family meals’, ‘start meals at regular hours’ and ‘spend time over their meals at the table’ tended to be deprived. Only the first item had been covered partially in the previous literature (Tani and Kusakari 2017; Ishida et al. 2017).

In contrast, if compared with the national average (Ueda 2022b), the prevalence of eating alone tended to be lower (mostly due to their inevitable food provision for their children); thus, the capability to ‘eat together with children’ was relatively higher. Nevertheless, future researchers (including national statisticians) should take into account the distinction between commensality (the act of eating together) and conviviality (the pleasure of eating together).

In addition, the wide-range analysis of products, procurement methods, pleasure and meal content supported the claim that the major problem facing the low-income single mothers in Japan is not the quantity but rather the quality of meals. They tended to be deprived of the capabilities to ‘purchase items other than cheap products at modest shops’, ‘prepare various and balanced dishes’, and ‘have convivial and gustative pleasures’, all of which the mothers highly valued. It is only from this total perspective that the contemporary (relative) nature of food poverty in Japan can be understood.

A complex association of conversion factors

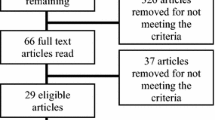

Multiple conversion factors were identified from our study on single mothers (Fig. 1), some of which were highly relevant to the dietary realities in low-SES families (e.g., van der Hejiden et al. 2021) and general households (e.g., Lappalainen et al. 1998). We summarise and discuss mainly the case of single mothers below, however, we also acknowledge that some of these factors might be applicable to much wider social groups (married mothers, single fathers, etc.).

Source Developed based on this study’s findings using the CA-based framework (Ueda 2021). Note 1 Each conversion factor (box) and the possible links (arrows) are exemplary and thus not exhaustive. The main purpose here is to present the relationships between all the relevant analytical concepts of the CA and to facilitate the explanation of the relevant factors

Association of Conversion Factors Influencing Well-Eating.

Among different conversion factors, (1) financial constraints and (2) time constraints constituted two of the major inhibiting factors for single mothers with low income in Japan, as it was for the low-SES households in Western countries (Dibsdall et al. 2002; O'Neill et al. 2004; Inglis and Crawford 2005; Lucan et al. 2012; Fielding-Singh 2017; van der Heijden et al. 2021). For the monetary constraint, the participants’ food choices were largely driven by economic rationality and constrained dimensions of their well-eating, including where to eat, where and what to buy and what meal to prepare. For the time constraint, one contribution of the study was the use of distinguishing between subjective and objective time constraints. The former limited the mothers’ motivation to cook (i.e., a decrease in well-eating), whereas, in some cases, a small effect from the latter enabled them to dine at regular hours with their children (i.e., increased well-eating).

(3) The absence of maternal health was one of the salient characteristics among the participants, all of whom experienced unstable mental conditions, including three with mental illness. This led to various negative influences on perceived time constraints, appetite and motivation to cook. Similarly, (4) there were also parenting difficulties that were related to development disorders and to school refusal that necessitated a great deal of care. This prevented the mothers from working long hours (i.e., reducing financial burden) and, in some cases, worsened the child-mother relationship and, consequently, the atmosphere at the table. These two factors were reported in previous qualitative food studies on Western low-income families (Backett-Milburn et al. 2006; Hardcastle and Blake 2016; Herman et al. 2012; Agrawal et al. 2018), but they have not received adequate attention in Japan, partly because they are not prominent in national statistics (MHLW 2016).Footnote 3 This omission highlights the limitations of quantitative studies of general, that is, non-food-specific, indicators in this population.

The fifth factor, (5) children’s tastes or, more precisely, picky eating, seriously reduced the mothers’ well-eating when coupled with their unique experiences (lack of money, limited consumption, food waste aversion, etc.). This gustative constraint was serious because the mothers had already sought expert treatment. Thus, it served as a more dominant factor than previously assumed in the relevant literature (Inglis and Crawford 2005; Teuscher et al. 2015; Fielding-Singh 2017). Notably, our study highlighted a negative sequence of events in which the lack of diverse meals leads to impoverished tastes among children and then to limited future meal options, with no opportunities for this cycle to be disrupted. Tastes need to be situated within the framework of the reproduction of social inequalities (Bourdieu 1979); they should not be regarded as physiological givens.

(6) Cooking abilities had a direct impact on achievements regarding where and what to eat. As exemplified by Mother #3, creative cooking abilities could enable them to overcome handicaps related to time, financial and mental health constraints. Given the aforementioned disadvantages, it can also be argued that the single mothers with low income needs to have superior cooking abilities to ordinary families to achieve an equal level of well-eating. Here, our study (and the participants’ self-reports) focused more on abilities that are related to ‘preparation’. However, it would be more accurate to use the term ‘food literacy’, which is broader (Vidgen and Gallegos 2014), so that our empirical insights can be linked to the literature on low-SES women (e.g., Dibsdall et al. 2002; Agrawal et al. 2018). That literature highlights more varied knowledge- and skill-related factors that are relevant to meal planning, food selection, preparation and eating.

The interviewed mothers had strongly internalised (7) gendered norms about ‘ideal mothers in the kitchen’. This tendency has also been reported in previous studies on low-SES women in Western countries (Eikenberry and Smith 2004; Lucan et al. 2012; Fielding-Singh 2017). However, it is particularly relevant to Japanese single mothers because the relative strength of those norms, which are not limited to food, can be inferred from a number of international comparisons between single mothers (IRHE 1999; Nakata et al. 1997). In addition to the social norms of ‘modern family’ (Ochiai 2019), this tendency was reinforced by their upbringings, in which their own mothers were not full-time workers and could dedicate sufficient time resources to daily family meals. Some mothers highlighted other factors, such as experience in the kitchen as housewives before their divorces and, as Fielding-Singh has suggested, their psychology in compensating for the many handicaps facing their children in other dimensions of living (Fielding-Singh 2017). These gendered identities functioned dually: high ideals for meal content enlarged the gap between ideal and reality, and negatively impacted the mothers’ well-eating, whereas their children’s well-eating was positively impacted by ensuring they could eat home-cooked meals.

(8) Food aid was an enabling factor for the well-eating of the mothers, although it was not detailed in the results section. This involved five mothers receiving provisions from food bank associations (although only two received regular monthly provisions) and one who regularly used kodomo shokudo (children’s free canteens which emerged as a response to increasing food insecurity in contemporary Japan) (Kimura 2019; Nomura and Feuer 2021). While food aid was positively evaluated by all the recipients because it relaxed their financial constraints or enabled conviviality, there were some mothers (#1 and #4) in relatively suburban areas who were in need of such aid but were excluded from the aid network.

(9) The constituents of the local food environment can also provide social support for the single mothers, not just the high-quality products that are mainly mentioned in the literature (Gravina et al. 2020; Rivera-Navaro et al. 2021). In this regard, the currently diminishing professional retailers (often small-scale and territorially grounded) should be further valorised. They provided both high-quality products and humanistic mental support for the mothers that would not be replaceable by large supermarkets and emerging drugstores.

Limitations

The first limitation relates to the sampling. It is necessary to increase the sample size by reaching out to single mothers experiencing severe economic poverty, as well as those living in sub-urban and rural areas. The second limitation is that this study did not enable an in-depth analysis of the relationships within functionings or within conversion factors. Lastly, the features ‘unique’ to the low-income single mothers are open to revision and critique. Further studies on single mothers with middle or high income,Footnote 4 or low-income mothers in general using a similar method, are necessary to identify the truly unique feature of eating well.

Aside from the above three limitations, the central challenge to the findings of this study concerns how this empirical evidence can be utilised to conceptualise ‘food poverty’ and how such a measurement method can be developed for the broader population. Although several entry points are possible, the most relevant one would be the Alkire and Foster (2011) method for multidimensional poverty measurement. This dual cut-off method consists of two steps: (i) setting a certain threshold for each functioning dimension, below which the person is identified as being deprived (e.g., ‘no opportunity for dining out’ as the threshold for the eating place dimension); and (ii) setting a cut-off threshold, above which the person is identified as being food-poor (e.g., ‘five deprived dimensions’ as the threshold). Rich insights about the norms, practices and underlying factors identified in this study can help to determine such thresholds.

Conclusion

The hidden nature of contemporary food poverty troubles researchers and policymakers in Japan. In the absence of in-depth knowledge about the circumstances of low-income single mothers, the prevalent view is that they do not have enough food and that financial constraints are the primary determinants of their well-eating. Instead, our study highlighted that these mothers are deprived of various types of capabilities, including not only that to obtain sufficient and nutritious food but also ones that have spatial, temporal, qualitative and affective aspects. Our empirical analysis also sheds light on multiple factors, which are not limited to monetary constraints, that can impact a mother’s capability to eat well. These findings challenge the previous reductionist understanding of food insecurity as well as demonstrating the theoretical pertinence of the CA to the analysis of contemporary food insecurity.

Although the small size of the sample and the regional context call for circumspection, the in-depth analysis of food poverty in Japan may have international implications. Even in the country with the worst poverty rate in the developed countries, the problem lies not in the quantity of available food but in the quality of eating lives. This finding can encourage officials in other countries, where conditions are superior to those that obtain in Japan, to also rethink their evaluative approaches to food poverty or insecurity.

This wider understanding of food poverty or insecurity also points to the limitations of existing social interventions, both in Japan and across the globe. Those interventions mainly entail monetary aid and the provision of food., however, other factors also contribute to capability deprivation. More proactive interventions, such as food education that ensures a minimal level of food literacy, the establishment of third places for convivial eating and even the provision of housekeeping services (to reduce the burden that mothers must shoulders as meal providers) would directly expand mothers’ capability to eat well (Ueda 2023). For such a proactive food policy to be developed, it is necessary to conduct further studies and public debates in order to set a minimum guaranteed standard of eating and, as the prerequisite of such a task, to determine what ‘eating well’ means for ourselves.

Data availability

Original data that support the findings of this study cannot be shared publicly due to the data availability restriction, which was approved by the Ethical Committee at Nagoya University. The data are, however, available from the author upon reasonable request and with the permission from the Ethical Committee.

Notes

For example, the analysis of ‘place of eating’ responses consisted only of frequencies of the pre-determined four types of eating (at home, bento [home-packed meals], taking in [eating purchased meals at home] and eating out), not of specific places.

Objective time constraint = 24 h – (working and commuting hours + national average for basic life activities [11.3 h] + national average for household chores in one-parent households [5.6 h]).

The national statistics on single mothers’ ‘troubles in life’ indicate that the prevalence of the following issues is comparatively low: ‘maternal health problems’ (13.0%), ‘parenting difficulties’ (13.1%) and ‘children’s handicaps’ (4.3%). Concerns about ‘children’s schooling and education’ (58.7%) and ‘family budgets’ (45.8%) were much more common.

The data of other 44 mothers (non-low-income) in the ELSM project would be useful for this purpose. However, comparative analysis was not performed in this article, because its primary purpose was to gain an in-depth understanding of low-income single mothers’ eating realities (which already required a large volume of results to be reported). Comparison using statistical analysis would be better coupled with further quantitative assessment using Alkire-Foster (2011) method.

References

Abe, A. 2006. Empirical analysis of relative deprivation in Japan using Japanese microdata [in Japanese]. Social Policy & Labour Studies 16: 251–275.

Abe, A. 2008. Child Poverty in Japan [in Japanese]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Agrawal, W., T.J. Farrell, E. Wethington, and C.M. Devine. 2018. Doing our best to keep a routine: How low-income mothers manage child feeding with unpredictable work and family schedules. Appetite 120: 57–66.

Alkire, S., and J. Foster. 2011. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Pubic Economics 95: 476–487.

Ashby, S., S. Kleve, R. McKechnie, and C. Palermo. 2016. Measurement of the dimensions of food insecurity in developed countries. Public Health Nutrition 19: 2887–2896.

Backett-Milburn, K.C., W.J. Wills, S. Gregory, and J. Lawton. 2006. Making sense of eating, weight and risk in the early teenage years: Views and concerns of parents in poorer socio-economic circumstances. Social Science & Medicine 63: 624–635.

Barret, C.B. 2010. Measuring food insecurity. Science 327: 825–828.

Bourdieu, P. 1979. La Distinction: Critique sociale du jugement. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

Cafiero, C., S. Viviani, and M. Nord. 2018. Food security measurement in a global context. Measurement 116: 146–152.

Carlson, S.J., M.S. Andrews, and G.W. Bickel. 1999. Measuring food insecurity and hunger in the United States: Development of a national benchmark measure and prevalence estimates. Journal of Nutrition 129 (2): 5105–5165.

Dibsdall, L.A., N. Lambert, and L.J. Frewer. 2002. Using interpretative phenomenology to understand the food-related experiences and beliefs of a select group of low-income UK women. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 34: 298–309.

Drèze, J., and A. Sen. 1989. Hunger and Public Action. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Eikenberry, N., and C. Smith. 2004. Healthful eating: Perceptions, motivations, barriers, and promoters in low-income Minnesota communities. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 104: 1158–1161.

Fielding-Singh, P. 2017. A taste of inequality. Social Sciences 4: 424–448.

Food and Agriculture Organisation. 2009. Declaration of the World Food Summit on Food Security. Rome: FAO.

Food and Agriculture Organisation. 2022. Prevalence of moderate and severe food insecurity in Japan. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#country/110. Accessed June 1, 2022.

Fujimori, K. 2018. Elderly women living alone and poverty. Trends in the Sciences 23 (5): 5–13.

Gravina, L., A. Jauregi, A. Estebanez, et al. 2020. Residents’ perceptions of their local food environment in socioeconomically diverse neighborhoods. Appetite 147: 104543.

Hardcastle, S.J., and N. Blake. 2016. Influences underlying family food choices in mothers from an economically disadvantaged community. Eating Behaviors 20: 1–8.

Hart, C. 2016. The school food plan and the social context of food in schools. Cambridge Journal of Education 46 (2): 211–231.

Hart, C., and A. Page. 2020. The capability approach and school food education and culture in England. Cambridge Journal of Education 40 (6): 673–693.

Hayashi, F., Y. Takemi, and N. Murayama. 2015. The association between economic status and diet-related attitudes and behaviors, quality of life in adults [in Japanese]. Japanese Journal of Nutrition & Dietetics 73: 51–61.

Hazano, S., A. Nakanishi, M. Nozue, H. Ishida, T. Yamamoto, A. Abe, and N. Murayama. 2017. The relationship between household income and food intake of Japanese schoolchildren [in Japanese]. Japanese Journal of Nutrition & Dietetics 75: 19–28.

Herman, A.N., K. Malhotra, G. Wright, J.O. Fisher, and R.C. Whitaker. 2012. A qualitative study of the aspirations and challenges of low-income mothers in feeding their preschool-aged children. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 9: 132.

Inglis, V.B.K., and D. Crawford. 2005. Why do women of low socioeconomic status have poorer dietary behaviours than women of higher socioeconomic status? Appetite 45: 334–343.

Institute for Research on Household Economics. 1999. Research on One-Parent Families in Six Countries [in Japanese]. Tokyo: IRHE.

Ishida, A., O. Kubo, K. Makino, and M. Taniguchi. 2017. Eating behavior and dietary awareness of mothers and children [in Japanese]. Journal of Food System Research 24: 99–112.

Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. 2019. National Survey on Households with Children in 2018. Tokyo: JILPT.

Kimura, A.H. 2019. Hungry in Japan: Food insecurity and ethical citizenship. Journal of Asian Studies. 77: 475–493.

Kubo, O., and A. Ishida. 2016. Dietary awareness and eating behavior of single female parents [in Japanese]. Journal of Rural Economics 88: 194–199.

Kudo, H., Y. Kito, and Y. Niiyama. 2017. Survey on the contents of diets focusing on the combination of dishes [in Japanese]. Journal of Rural Economics 88: 410–415.

Lappalainen, R., J. Kearney, and M. Gibney. 1998. A pan EU survey of consumer attitudes to food, nutrition and health. Food Quality & Preference 9: 467–478.

Lucan, S.C., F.K. Barg, A. Karasz, C.S. Palmer, and J.A. Long. 2012. Perceived influences on diet among urban, low-income African Americans. American Journal of Health Behavior 36: 700–710.

Matsuda, O., A. Ishida, and A. Nishizawa. 2020. Factors affecting the dietary lives in mother-to-child households [in Japanese]. Journal of Food System Research 26: 217–233.

Ministry of Health, and Labour and Welfare. 2016. National Survey on Single-Parent Households [in Japanese]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Moscovici, S. 2001. Social Representations. New York: New York University Press.

Munt, A.E., S.R. Partridge, and M. Allman-Farinelli. 2017. The barriers and enablers of healthy eating among young adults: A scoping review. Obesity Review 18: 1–17.

Nakata, T., K. Sugimoto, and A. Morita. 1997. Single Mothers in Japan and US [in Japanese]. Kyoto: Minerva Shobo.

Nishi, N., C. Horikawa, and N. Murayama. 2017. Characteristics of food group intake by household income in National Health and Nutrition Survey. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 26: 156–159.

Nomura, A., and H.N. Feuer. 2021. Institutional food literacy in Japan’s children’s canteens. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 27 (2): 55–71.

Ochiai, E. 2019. Families in the 21th Century (4th Edition) [in Japanese]. Tokyo: Yuhikaku.

O’Neill, M., D. Rebane, and C. Lester. 2004. Barriers to healthier eating in a disadvantaged community. Health Education Journal 63: 220–228.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2021. Poverty rate. https://data.oecd.org/inequality/poverty-rate.htm. Accessed March 1, 2023.

Peng, W., and E.M. Berry. 2019. The concept of food security. In Encyclopedia of Food Security and Sustainability (vol. 2), ed. P. Ferranti, E.M. Berry, and J.R. Anderson, 1–7. Elsevier.

Poulain, J.P. 2017. The Sociology of Food. New York: Bloombury.

Poulain, J.P. 2002a. The contemporary diet in France. Appetite 39: 43–55.

Poulain, J.P. 2002b. Manger Aujourd’hui: Attitudes, Normes et Pratiques. Paris: Privat.

Rivera-Navaro, J., P. Conde, J. Diez, et al. 2021. Urban environment and dietary behaviours as perceived by residents living in socioeconomically diverse neighbourhoods: A qualitative study in a Mediterranean context. Appetite 157: 104983.

Sasaki, S., R. Yanagibori, and K. Amano. 1998. Self-administered diet history questionnaire developed for health education. Journal of Epidemiology 8: 203–215.

Sen, A. 1980. Equality of what? Tanner Lecture on Human Values 1: 197–220.

Sen, A. 1982. Poverty and Famines. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. 1992. Inequality Reexamined. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. 1993. Positional objectivity. Philosophy & Public Affairs 22 (2): 126–145.

Sobal, J. 2001. Sample extensiveness in qualitative nutrition education research. Journal of Nutrition Education Behavior 33: 184–192.

Tani, A., and H. Kusakari. 2017. Characteristics of food consumption in single-mother households suffering from poverty in Japan [in Japanese]. Journal of Rural Economics 88: 406–409.

Teuscher, D., A.J. Bukman, M.A. van Baak, E.J. Feskens, R.J. Renes, and A. Meershoek. 2015. Challenges of a healthy lifestyle for socially disadvantaged people of Dutch, Moroccan and Turkish origin in The Netherlands. Critical Public Health 25: 615–626.

Tomura, K. 2016. Trends observed in poverty rates across 47 prefectures in Japan [in Japanese]. Yamagata University Bulletin 13: 33–53.

Townsend, P. 1979. Poverty in the United Kingdom. London: Penguin Books.

Ueda, H. 2021. Establishing a theoretical foundation for food education in schools using Sen’s capability approach. Food Ethics 6: 1–18.

Ueda, H. 2022a. What is eating well? Capability approach and empirical exploration with the population in Japan. Appetite 170: 105874.

Ueda, H. 2022b. The norms and practices of eating well: In conflict with contemporary food discourses in Japan. Appetite 175: 106086.

Ueda, H. 2023. Food aid and related challenges in Japan: Moving towards equality of ‘capability’ not ‘consequences’ [in Japanese]. Journal of Food System Research 29 (4): 243–248.

Ueda, H., and J.P. Poulain. 2021. What is gastronomy for the French? An empirical study on representation and eating model in the contemporary France. International Journal of Gastronomy & Food Sciences 25: 100377–100388.

van der Hejiden, A., H.T. Molder, G. Jager, and B.C. Mulder. 2021. Healthy eating beliefs and the meaning of food in populations with a low socioeconomic position. Appetite 161: 105135.

Vidgen, H.A., and D. Gallegos. 2014. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite 76: 50–59.

Visser, S.S., and H. Haisma. 2021. Fulfilling food practices: Applying the capability approach to ethnographic research in the Northern Netherlands. Social Science & Medicine 272: 113701.

Zorbas, C., C. Palermo, A. Chung, I. Iguacel, A. Peeters, R. Bennett, and K. Backholer. 2018. Factors perceived to influence healthy eating: A systematic review and meta-ethnographic synthesis of the literature. Nutrition Review 76: 861–874.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [grant number: 21J01732, 22K14956] and the Lotte Foundation (LF000805). I am also grateful to Ms. Yuriko Fukushima at Osaka Prefectural Center for Youth and Gender Equality for the assistance of data analysis and Ms. Tomoyo Jin at LivEQuality and Mr. Tomohiro Imai at Eskuru Association for Single Parents Support for the initial validity assessment of the interview questions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This research is in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Nagoya University (ID: 2021–1).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ueda, H. Multidimensional Food Poverty: Evidence from Low-Income Single Mothers in Contemporary Japan. Food ethics 8, 13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41055-023-00123-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41055-023-00123-9