Abstract

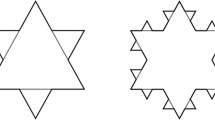

The concept of geometry may evoke a world of pure platonic shapes, such as spheres and cubes, but a deeper understanding of visual experience demands insight into the perceptual organization of naturalistic form. Japanese gardens excel as designed environments where the complex fractal geometry of nature has been simplified to a structural core that retains the essential properties of the natural landscape, thereby presenting an ideal opportunity for investigating the geometry and perceptual significance of such naturalistic characteristics. Here, fronto-parallel perspective, asymmetrical structuring of the ground plane, spatial arrangement of garden elements, tuning of textural qualities and choice of naturalistic form, are presented as a set of physical features that facilitate a systematic analysis of Japanese garden design per se, as well as the geometry of the particular naturalistic features that it aims to enhance. Comparison with Western landscape design before and after contact between Western and Eastern hemispheres illustrates the degree of naturalness achieved in the Japanese garden, and suggests how classical Western landscape design generally differs in this regard. It further reveals how modern Western gardens culminate in a different naturalistic geometry, thus also a distinctly different vision of the natural landscape, even if these designs were greatly influenced by the gardens of China and Japan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Intricate rock formations were achieved by glueing together individual rocks into conglomerates of highly convoluted structures using glutenous rice, a simple everyday ingredient with surprisingly resilient physical properties in exterior applications. Such intricate formations reflect the supposed intellectual ideals of the immortal sage, superseding natural form, and strongly distinguish the vertical rock piles of Chinese landscape design from the demure, simplified rock arrangements associated with Japanese garden design.

The first Japanese diplomatic mission to China returned in 607 CE with many observations detailing Chinese culture, art, religion and politics, including descriptions of Chinese landscape practices (Young and Young 2005).

In the centuries following the period when Kobori Enshū was active, until the present, various other master garden designers have produced their own great gardens, but are not discussed here because the classical Japanese garden has reached maturity by this time.

Various hand drawn copies of Fan Kuan’s famous work, Travellers among mountains and streams, reveal just how difficult it is to capture the apparent ease and spontaneity achieved in the master’s hand. All of the copies appear rigid, repetitive and interestingly, lack the monumental scale conveyed by the original work (van Tonder 2018).

[Pine Trees, Tōhaku Hasegawa (1539–1610). Pair of six-paneled folding screens. Ink on paper. Tokyo National Museum. Left and right halves of the set of two folding screens can be retrieved from the public internet domain at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sh%C5%8Drin-zu_by%C5%8Dbu#/media/File:Hasegawa_Tohaku_-_Pine_Trees_(Sh%C5%8Drin-zu_by%C5%8Dbu)_-_left_hand_screen.jpg and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sh%C5%8Drin-zu_by%C5%8Dbu#/media/File:Hasegawa_Tohaku_-_Pine_Trees_(Sh%C5%8Drin-zu_by%C5%8Dbu)_-_right_hand_screen.jpg. Accessed on 20 June 2018].

Given the influence of Chinese culture on Japanese garden design, one may assume that the use of moss originated in China, when in fact this is one of the uniquely Japanese contributions to landscape art. The entire body of classical Chinese literature hardly ever mentions moss. While appreciating Japanese gardens to some extent, early Western visitors to Japan apparently did not fully grasp its aesthetic utility, with the sixteenth century CE Jesuit priest, João Rodrigues, famously writing about tea gardens covered in ‘moss and other debris’ (Cooper 2001).

References

Akisato R (1799) Miyako rinsen meishō zue (Illustrated guide to famous places in and around the capital). Kyoto, Japan

Allain Y, Christiany J (2006) L’art des jardins en Europe. Citadelles, Paris

Arnheim R (ed) (1966) Order and complexity in landscape design. In: Toward a psychology of art. University of California Press, Berkeley

Arnheim R (1988) The power of the centre: a study of composition in the visual arts. University of California Press, Berkeley

Baltrušaitis J (1978) Jardins en France 1760–1820. Caisse National des Monuments Historiques et des Sites, Paris

Brown J (2011) The Omnipotent Magician: Lancelot “Capability” Brown, 1716–1783. Chatto & Windus, London

Cahill JF (2012a) Lecture 1: introduction and Pre-Han Pictorial Art, and Lecture 2: Han Painting and Pictorial Art. In: A pure and remote view: visualizing early Chinese landscape painting (Series of twelve video-recorded lectures). The Institute for East Asian Studies at U.C. Berkeley. Available via James Cahill. http://jamescahill.info/a-pure-and-remote-view. Cited 19 June 2018

Cahill JF (2012b) Lecture 7a: early Northern Song landscape. In: A pure and remote view: visualizing early Chinese landscape painting (Series of twelve video-recorded lectures). The Institute for East Asian Studies at U.C. Berkeley. Available via James Cahill. http://jamescahill.info/a-pure-and-remote-view. Cited 19 June 2018

Clark K (2010) The Nude: a study in ideal form. New edition. The Folio Society, London

Colvin H (1995) [1954] A biographical dictionary of British Architects 1600–1840, 3rd edn. Yale University Press, New Haven

Conan M (2006) Perspectives on Garden Histories, vol 21. Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium Series on the History of Landscape Architecture. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC

Cooper M (ed) (2001) João Rodrigues’s Account of Sixteenth-Century Japan. Hakluyt Society, London

da Vinci L (Circa 1600) Treatise on Painting (trans: McMahon AP [1956]). Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Dumoulin H (2005) Zen Buddhism: a history. 2: Japan. Treasures of the world’s religions. World Wisdom, Bloomington

Ebrey PB (1999) The Cambridge illustrated history of China. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Etō S (1979) Sōami Shōkei. Nihon bijutsu kaiga zenshū, Shūeisha

Gardner H (1995) Art through the ages (10th Reiss edition). Harcourt College Publishers, Fort Worth

Girshick AR, Landy MS, Simoncelli EP (2011) Cardinal rules: visual orientation perception reflects knowledge of environmental statistics. Nat Neurosci 14(7):926–932

Hazlehurst FH (1980) Gardens of illusion: the genius of André Le Nostre. Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville

Honda H, Fisher JB (1978) Tree branch angle: maximizing effective leaf area. Science 199:889–890

Itō T, Iwamiya T (1972) The Japanese Garden: an approach to nature. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut

Itō T, Kuzunishi S (1973) Space and illusion in the Japanese Garden. Weatherhill, New York

Jennings G (1986) Impressionist painters. Octopus Book, London

Julesz B (1981) Textons, the elements of texture perception, and their interactions. Nature 290(5802):91–97

Julesz B (1995) Dialogues on perception. MIT Press, Cambridge

Kean MP, Ohashi H (1996) Japanese garden design. Tuttle, Tokyo

Kemp M (1990) The science of art: optical themes in western art from Brunelleschi to Seurat. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut

Keswick M (2003) The Chinese garden. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Kirchner TY (2015) Dialogues in a dream: the life and Zen teachings of Musō Soseki. Wisdom Publications, Somerville

Komar V, Melamid A (1995) Komar + Melamid: the most wanted paintings. Available via Dia center for the arts. http://awp.diaart.org/km/index.php/homepage.html. Cited 14 May 2018

Kristjánsson A, Heimisson P, Róbertsson G, Whitney D (2013) Attentional priming releases crowding. Atten Percept Psychophys 75(7):1323–1329

Kuck L (1968) The world of the Japanese Garden: from Chinese origins to modern landscape art. John Weather-Hill, New York

Kuitert W (2002) Themes in the history of Japanese garden art. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu

Kuitert W (2013) Japanese Robes, Sharawadgi, and the landscape discourse of Sir William Temple and Constantijn Huygens. Gard Hist 41(2):172

Levi D (2008) Crowding—an essential bottleneck for object recognition: a mini-review. Vis Res 48(5):635–654

Mares E, Nomura K (eds) (2008) Kobori Enshu: a tea master’s harmonic brilliance. The great masters of gardens of Kyoto, vol 3. Kyoto Tsushinsha Press, Kyoto

McManus IC, Weatherby P (1997) The golden section and the aesthetics of form and composition: a cognitive model. Empir Stud Arts 15(2):209–232

Miura K, Sukemiya H, Yamaguchi E (2011) Goodness of spatial structure in Japanese rock gardens. Jpn Psychol Res 53(4):391–401

Naito A, Nishikawa T (1977) Katsura: a princely retreat. Kodansha International, Tokyo

Nitschke G (1991) Japanese gardens: right angle and natural form. Benedikt Taschen, Cologne

Odegaard B, Wozny DR, Shams L (2015) Biases on visual, auditory, and audiovisual perception of space. PLoS Comput Biol 11(12):e1004649

Oyama H (1995) Ryoanji Sekitei: Nanatsu no Nazo wo toku (Ryoanji Rock Garden: Resolving Seven Mysteries). Kodansha, Tokyo

Panofsky E (1927) Die Perspektive als “symbolische Form” (Perspective as Symbolic Form). Teubner

Parke L, Lund J, Angelucci A, Solomon JA, Morgan M (2001) Compulsory averaging of crowded orientation signals in human vision. Nat Neurosci 4(7):739–744

Ponsonby-Fane RAB (1956) Kyoto: the old capital of Japan, 794–1869. The Ponsonby Memorial Society, Kyoto

Prevot P (2006) Histoire des jardins. Editions Sud Ouest, Bordeaux

Rutherford S (2016) Capability Brown and his landscape gardens. National Trust Books, London

Shingen (1466) Senzui Narabi ni Yagyou no Zu (Illustrations for designing mountain, water and hillside field landscapes). Sonkeikaku Library, Sonkeikaku Sōkan Series. Ikutoku Zaidan, Tokyo

Silbergeld J (1982) Chinese painting style: media, methods, and principles of form. University of Washington Press, Seattle

Slawson DA (1987) Secret teachings in the art of Japanese gardens. Kodansha, Tokyo

Takei J, Keane MP (2001) Sakuteiki: visions of the Japanese garden: a modern translation of Japan’s gardening classic. Tuttle Publishing, Boston

Van Tonder GJ (2018) Black ink, white fog: the genius of Tōhaku Hasegawa. S Afr J Art Hist 33(4):21–37 (Special issue on Aesthetic Experience, in press)

Van Tonder GJ, Lyons MJ (2005) Visual perception in Japanese rock garden design. Axiomathes 15(3):353–371 (special issue on Cognition and Design)

Van Tonder GJ, Lyons MJ, Ejima Y (2002) Visual structure of a Japanese Zen garden. Nature 419:359–360

Vassort J (2017) L’Art des Jardins de France. Editions Ouest-France, Rennes

Voronoi G (1908) Nouvelles applications des paramètres continus à la théorie des formes quadratiques. Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 1908(133):97–178

Wenzler C (2003) Architecture du jardin. Editions Ouest-France, Rennes

Williford JR, von der Heydt R (2013) Border-ownership coding. Scholarpedia, 8(10):30040. Available via Scholarpedia. http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Border-ownership_coding Cited 8 June 2018

Yarbus AL (1967) Eye movements and vision. Plenum Press, New York

Young D, Young M (2005) The art of the Japanese garden. Tuttle, Singapore

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Tonder, G.J. Visual Geometry of Classical Japanese Gardens. Axiomathes 32, 841–868 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-018-9414-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-018-9414-2