Abstract

Employees remaining silent about ethical aspects of work or organization-related issues, termed employee ethical silence, perpetuates misconduct in today’s business setting. However, how and why it occurs is not yet well specified in the business ethics literature, which is insufficient to manage corporate misconducts. In this research, we investigate how and when exploitative leadership associates with employee ethical silence. We draw from the conservation of resources theory to theorize and test a cognitive resource pathway (i.e., work meaningfulness) and a moral resource pathway (i.e., moral potency) to explain the association between exploitative leadership and employee ethical silence. Results from two studies largely support our hypotheses that work meaningfulness and moral potency mediate the effect of exploitative leadership on ethical silence contingent on performance reward expectancy. Theoretical and practical implications are thoroughly discussed in the paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

“Why We’re Seeing So Many Corporate Scandals” is a persistent question among business ethics scholars and practitioners (Mukherjee, 2016). Even though organizations promote misconduct prevention, employees continue to witness unethical behaviors in their organizations yet choose to stay silent (Fortune, 2020; Walsh, 2021). Perpetuating white-collar crime (Walsh, 2021), ethical silence is the “conscious withholding of information, suggestions, ideas, questions, or concerns” about ethical aspects of work or organization-related issues (Morrison, 2011, p. 377). Research on employee silence in general has demonstrated its detriments on a range of job attitudes, task performance, and organizational citizenship behavior (Hao et al., 2022), which highlights the need to better understand how and why it occurs.

So far, the silence literature has typically used the behavioral inhabitation system to explain its occurrence (Sherf et al., 2021). As an avoidance behavior, employee silence is conceptualized as independent of voice and is motivated by moving away from negative stimuli, such as perceived risks/harms in the environment from acting (Sherf et al., 2021). According to this perspective, silence is induced by negative experience with leaders (e.g., leader narcissism, Hamstra et al., 2021; aggressive humor, Wei et al., 2022; destructive personality, Song et al., 2017), which threatens and depletes employees’ personal and social resources, resulting in harm to the self (e.g., lack of psychological safety). However, recent meta-analysis (Hao et al., 2022) notes inconclusive findings. Among various leadership styles examined, not all leader-related variables are statistically related to different types of employee silence, suggesting several research limitations.

First, past research has focused on silence in general without specifying its content. This lack of specificity is insufficient to capture the complexities involved in the aversion to different types of harm to the self; nor does it address employee silence from an ethical perspective. In the context of business ethics, because employee ethical behavior can often be elusive (Anteby & Anderson, 2016; Sonenshein, 2007; Trevino, 1986), it is likely that employees speak up against suboptimal work processes but remain silent on ethical issues. Hence, we introduce ethical silence, ground it in the existing silence literature, and specify it as concerning the suppression of ideas or concerns about the ethical aspect of work or organization.

Second, despite the available knowledge of the association between abusive supervision and employee silence (e.g., Kiewitz et al., 2016), we know relatively less about different leadership styles that can be associated with ethical silence specifically. While one’s encounter with leaders can involve interpersonal provocation (viz. abusive supervision), employees can also be taken advantage of by leaders who excessively seek self-interest, termed exploitative leadership (Schmid et al., 2018). Defined as using the position of authority for personal gains (Schmid et al., 2019), exploitative leadership is a recently studied type of dark leadership style (Webster & Brough, 2021). Growing evidence shows exploitative leadership can harm employee task (Syed et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021) or service performance (Ye et al., 2022, 2023; Sun et al., 2023), turnover intention (Syed et al., 2021), innovative behavior (Wang et al., 2021b), and unethical behaviors (Cheng et al., 2023; Lyu et al., 2022). Notwithstanding their contributions, we still know relatively little about a wider range of its impact, including on ethical silence.

Third, as aversive in nature, ethical silence moves away from potential risks to the self so as to protect limited resources and reduce resource loss (Xu et al., 2015). Hao et al. (2022) in their recent meta-analysis draws from the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) to identify factors that contribute to silence. However, there is an insufficient investigation of the underlying mechanism that explains the association of one’s encounter with leaders and their subsequent silence response. Of the limited studies in this direction, they mainly focus on one mediation pathway, such as psychological safety (Duan et al., 2018), emotional exhaustion (Xu et al., 2015), or leader trustworthiness (Hamstra et al., 2021), which captures only one element of resources. From a COR theory perspective, people have a range of resources that are valuable for goal pursuit (Hobfoll et al., 2018). So, a fuller understanding of how ethical silence is underpinned by resource conservation requires the investigation of multiple resources in the process.

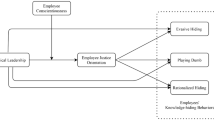

We, therefore, aim to investigate how and when exploitative leadership associates with employee ethical silence. To do so, we draw from COR theory to theorize and test a cognitive resource pathway (i.e., work meaningfulness) and a moral resource pathway (i.e., moral potency) for a fuller understanding of the processes. Work meaningfulness is the cognitive processing of the worth or value in work judged by personal ideals or standards (Lee et al., 2017). A resource perspective helps to integrate the work- and person-centric treatment of work meaningfulness (De Boeck et al., 2019). Moral potency is a valued moral resource that describes the combination of the experienced sense of ownership over the moral aspect of one’s environment, efficacy, and courage to perform ethically (Hannah & Avolio, 2010; Hannah et al., 2011). By simultaneously testing work meaningfulness and moral potency, we capture the various resources leadership offers to its followers (e.g., Sungu et al., 2020). In addition, COR theory argues that resource conservation is motivated differently depending on the pool of resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018). As performance reward expectancy relates to the perceived possibility of receiving one of the most important resources in organizational life, i.e., material rewards (Vroom, 1964), we believe it will influence the extent to which employees orient their resource preservation and development processes. Therefore, drawing from COR theory and supplementing with expectancy theory, we further propose that performance reward expectancy moderates the mediated relationships between exploitative leadership and employee ethical silence via work meaningfulness and moral potency. The research model is depicted in Fig. 1.

Our research findings make three main contributions to business ethics research. First, we extend the current understanding of employee silence by specifying its content. This is a worthwhile endeavor, given that ethical silence is a pervasive and persistent issue vis-a-vis growing concerns over ethical scandals in business. Second, we clarify the underlying mechanism through which exploitative leadership associates with ethical silence by theorizing and testing the processes related to two valued resources. The finding provides a relatively fuller picture by adding fresh insights into the mediation of work meaningfulness and moral potency. Third, we enrich the limited but growing literature on exploitative leadership by introducing ethical silence as an important employee outcome that broadens the scope of exploitative leadership research. In this direction, we also provide a more nuanced understanding of the boundary conditions (i.e., performance reward expectancy) related to when exploitative leadership influences ethical silence. By demonstrating the moderating role of performance reward expectancy, we enrich understandings of when leaders’ exploitation is more or less harmful to employees' resources and subsequent behaviors. The findings also provide insights into how to circumvent ethical silence.

Theory and Hypothesis

Conservation of Resource Theory

COR theory is a classic motivation theory that explains human behavior from the processes by which people conserve and acquire resources. Its fundamental tenet is that people are motivated to preserve current resources, protect against resource loss, and acquire new resources, which refer to things that people value (Hobfoll, 1989). In COR theory terms, resource is the foundational construct and is defined broadly to capture the co-existence of different resources that are valuable for people to achieve strategic pursuits (Halbesleben et al., 2014). The goal-directed definition of resources helps to clarify the notion of value that previous conceptualizations of resources are unable to solve (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Relatedly, equifinality describes the nature of resources in COR theory, i.e., in a given situation, multiple valuable resources are at work (Kruglanski, 1996). This suggests that a fuller understanding of people’s behavioral responses in each situation requires tapping into more than just one resource process.

Notably, resources are different from the outcomes that their value is attached to (Halbesleben et al., 2014). So, a given situation impacts the gain or loss of multiple resources that could help an individual attain a goal. Regarding employee ethical silence, we explore both a cognitive resource pathway and a moral resource pathway resulting from exploitative leadership.

Exploitative Leadership and Ethical Silence

From the COR theory perspective, we argue that exploitative leadership serves as a stressor in the organization (Schmid et al., 2019) in which (a) employee resources are threatened, (b) there is an actual loss of resources or (c) the expected returns on employee resource investment are not realized (Hobfoll, 2001). Thus, employees are motivated to conserve remaining resources and reduce further resource loss, in which keeping silent on ethical issues becomes a safer response.

Specifically, exploitative leaders use a wide range of tactics to exploit followers for leaders’ own interests, including acting egoistically, manipulating, exerting pressure, and undermining development (Schmid et al., 2019). Prior research has suggested that these behaviors associated with exploitative leadership are resource-draining for employees (Guo et al., 2021). This is firstly due to the threatening situation exploitative leadership creates. For instance, exploitative leaders may disregard employees’ wellbeing and pressure them to overwork or fulfill an overly demanding task (Gerpott & Van Quaquebeke, 2022). This consumes employees’ resources that are essential for thriving at work and relational attachment (e.g., Cheng et al., 2023; Elsaied, 2022; Wu et al., 2020). Secondly, exploitative leaders push for employee productivity, at least in the short term, that pays into their own performance record rather than providing employees with developmental opportunities (Gerpott & Van Quaquebeke, 2022). This means employees’ investment on work is not realized. As employees are depleted without being granted any opportunities for obtaining new resources from exploitative leaders, these employees are motivated to take a defensive approach to conserve resources and minimize the detriments of resource loss.

In this context, remaining silent, particularly on ethics-related matters (viz. employee ethical silence), is a viable coping strategy for resource conservation because exploitative leadership is unethical in nature (Schmid et al., 2019). When employees choose to isolate themselves from business ethics in a silent way, they are less likely to confront exploitative leaders who have high tolerance of unethical conducts. Otherwise, employees run the risks of further losing limited resources and instead they can focus on preventing further loss (Bolton et al., 2012; Dyne et al., 2003; Greenberg & Edwards, 2009). Also, in reality, ethics are often at the peripheral of one’s job, with the core tasks on achieving the bottom-line (Calabretta et al., 2011; Greenbaum et al., 2012). As exploitative behavior is an unpleasant source of work stress (Guo et al., 2021; Majeed & Fatima, 2020), employees are motivated to conserve resources on tasks that are more closely related to their leader demand, but not on tasks that exploitative leaders do not align with. Taken together, the motivation to conserve resources, coupled by the fear of further loss, motivates employees to act in a silent fashion in the ethical domain. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 1

Exploitative leadership is positively associated with ethical silence.

The Mediating Role of Work Meaningfulness: A Cognitive Resource Pathway

To explain how exploitative leadership relates to ethical silence, we draw from COR theory which argues that resource loss/gain mediates the effects of stressors on subsequent behaviors (Hobfoll et al., 2012). We first study work meaningfulness as a mediating variable since it represents a cognitive resource that describes the amount of significance one perceives in work (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). Based on COR theory, we predict that work meaningfulness is dampened by exploitative leadership, which in turn makes employees more likely to stay silent on ethical issues at work.

Exploitative leadership constrains the recognition, meaning, and growth that employees could see in their work. Under exploitative leaders, employees are unlikely to be valued, assigned interesting tasks, or given the opportunities for professional development or career progression, no matter how well they perform or how much effort they put into work (Wang et al., 2021a). According to COR theory, people actively seek to create a world that will provide them with pleasure and success (Parker et al., 2017). However, exploitative leadership limits the chances for employees to make a positive impact on their life through their work roles and activities (Rosso et al., 2010). Research shows that when individuals are not treated well or not having control over their work, they are less likely to see the meaning in their work (Humphrey et al., 2007; Lepisto & Pratt, 2017; Stein et al., 2019). In addition, leaders’ exploitation is a threatening situation (Schmid et al., 2019) in which employees worry about their prospects in the organization and feel disappointed or helpless, because exploitative leaders do not take subordinates’ goals as priority. This makes it difficult to cope with leaders’ exploitation, thereby reducing their work meaningfulness. Furthermore, exploitative leadership also results in the workplace's unethical climate that can undermine the sense of meaningfulness in the work (Levine & Boaks, 2014).

Subsequently, as a key job resource (Lee et al., 2017), reduced work meaningfulness that results from having an exploitative leader motivates employee ethical silence. Work meaningfulness encompasses positive psychological states of fulfillment and satisfaction (Rosso et al., 2010). When it is reduced, employees are less likely to sense a safe environment or engage actively at work (Hirschi, 2012; Lee et al., 2017). The reduced motivational resources hence activate the behavioral inhibition system such that employees remain silent on ethical issues at work in order to protect their limited resources. Indeed, research reveals that a low level of work meaningfulness increases resource depletion, stress responses (Rosso et al., 2010; Schnell et al., 2013) and turnover intention (Leunissen et al., 2018). In other words, the motivation of resource conservation in COR theory terms activates the behavioral inhibition system that results in ethical silence.

Reduced work meaningfulness due to exploitative leadership is particularly relevant for employee responses in the ethical domain. An emergent line of research in the business ethics field suggests that the values people place in their work lives have an ethical component (Wang & Xu, 2019). The amount of significance employees attach to the work is underpinned by an authentic connection with a broader life purpose that can impact the broader community (Bailey & Madden, 2016). In this respect, employees who do not see meaningfulness in their work with an exploitative leader are unlikely to be guided by a self-transcendent life purpose, hence remain silent on ethical issues at work.

In summary, according to COR theory, which links stressors, resource gain/loss, and behavior, we suggest that employees exploited by their leaders experience a reduction in their work meaningfulness that contributes to increased ethical silence.

Hypothesis 2

Work meaningfulness mediates the association between exploitative leadership and ethical silence.

The Mediating Role of Moral Potency: A Moral Resource Pathway

Next, we study moral potency as a moral resource pathway that explains the association between exploitative leadership and ethical silence. Moral potency represents “an individual’s ethical psychological resource” (Hannah & Avolio, 2010, p. 292) that explains whether one will both know and act in the right way in face of complex, challenging moral dilemmas. When introducing this term, Hannah and Avolio (2010) define it as the experienced sense of ownership over the moral aspect of the environment, “reinforced by efficacy beliefs in the capabilities to act to achieve moral purpose in that domain, and the courage to perform ethically in the face of adversity and perseverate through changes” (pp. 291–292). Based on COR theory, we argue that exploitative leadership is detrimental to the development of moral potency, which has downstream implications for ethical silence.

Specifically, research shows that being led by leaders who emphasize the ethical treatment of employees is crucial for building or developing employees’ moral resources (Bandura, 1997; Hannah et al., 2011). Unfortunately, exploitative leadership is unethical in their treatment of employees in that these leaders are solely self-centered and exploit the limited resources (e.g., time and energy) employees are supposed to use to build their moral capabilities. For instance, by overburdening subordinates or exerting too much pressure on them, exploitative leaders distort moral justification or engagement, which decreases the capability to think and behave ethically (Cheng et al., 2023; Lyu et al., 2022). Exploitative leadership behaviors shift employees’ identity and motivations from focusing on moral aspects of the work to a focus on the result orientation that benefits leaders, hence reducing their sense of moral efficacy and moral ownership.

In addition, exploitative leadership processes, such as ignoring employee considerations, are unlikely to offer employees opportunities to successfully achieve moral courage. This lack of mastery experience leads to employees having insufficient belief in enacting strategies that address future ethical dilemmas, hence remaining silent on ethical issues at work (c.f., Bandura, 1997). There is also research showing that when employees lack valuable resources such as feedback from their leaders, they feel discouraged to communicate openly and tend to remain silent (Park & Keil, 2009). A similar argument can be made here because exploitative leadership acts egoistically and takes credit of employees' work without providing feedback or opportunities for their progress (Stouten & Tripp, 2009). Further, without having leaders displaying exemplary behaviors, employees do not receive the resources from exploitative leaders that they have the capability to resolve ethical issues, hence reducing moral courage.

In turn, reduced moral potency under exploitative leadership has important implications for employee ethical silence. When employees see an organization-related ethical issue present, they assess the risks and benefits of remaining silent (Chou & Chang, 2020). Because this assessment is subjective, people look at their pool of resources to make their coping strategies. Research has shown that silence is a self-protection mechanism based on fears of consequences, self-doubt, or lack of confidence (e.g., Morrison et al., 2015). According to COR theory, people unable to build valuable resources (e.g., moral potency) become motivated to prevent future resource loss and do not perform optimally. In this sense, employees who cannot develop moral potency due to having an exploitative leader are at a disadvantaged position to assess their capability of effectively making a change on ethics-related issues at work (Hobfoll, 2011). When this occurs, remaining silent on ethical issues becomes a logical solution. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3

Moral potency mediates the association between exploitative leadership and ethical silence.

The Moderating Role of Performance Reward Expectancy

Although we expect exploitative leadership to hamper employees’ cognitive and moral resources that are necessary for averting ethical silence, COR theory suggests that people differ in the extent to which they experience resource loss and subsequent negative consequences. A key factor in this difference is that people with fewer resources are more vulnerable to resource loss (Hobfoll, 1989). In the organizational context, one of organizational elements that could influence the resource stock of employees at work is performance reward expectancy, defined as “the perceived possibility of obtaining material rewards provided by the organization matching their contributions” (Vroom, 1964). Organizations have long utilized incentives, traced to expectancy theory (Lawler, 1973; Skinner, 1938), to create an expectancy that motivates employees exert efforts in organization-valued goal pursuits (Wabba & House, 1974). Research suggests that the expectancy of a positive outcome is a valuable resource in COR theory terms (Feldman et al., 2015). Therefore, we supplement COR theory with expectancy theory to argue that performance reward expectancy moderates the relationship between exploitative leadership and work meaningfulness/moral potency.

Specifically, prior research has shown that a higher performance reward expectancy motivates employees to perform rationally (Lawler, 1973). In other words, employees are motivated to allocate their limited resources to tasks central to task performance, but not to other aspects of the work. This effectively reduces employee resources related to meaning seeking. In business, performance is often operationalized as productivity (Cadsby et al., 2007), which is the target of leaders’ exploitation that benefits the leaders’ own performance records (Gerpott & Van Quaquebeke, 2022). As performance reward expectancy can occur both at the individual level and the team level, directing attention can be expected at both levels towards high-performance goals (e.g., Baker & Delpechitre, 2013; Garbers & Konradt, 2014; Haines & Taggar, 2006; Han et al., 2015). So, when this occurs (i.e., at a higher level of reward expectancy), employees have less available resources to create a world with meaning and hence more likely to suffer from resource loss in the form of reduced work meaningfulness when faced with leaders’ exploitation. On the contrary, at a lower level of reward expectancy, employees do not have a credible anticipation that they will receive matching future rewards if they perform well (Frankort & Avgoustaki, 2022). As expectancy theory assumes, when this occurs, employees are not motivated to exert all their resources towards task fulfillment that serve the benefits of leaders. This makes them less vulnerable to resource loss in terms of reduced significance they see in their work for themselves.

In addition, previous research on reward expectancy suggests that a high-performance reward expectancy leads people to be more motivated to materialize their work efforts and performance (Zeng et al., 2018). Therefore, when faced with leaders’ exploitation, employees become more sensitive, and their feelings about resource loss are more intense, which leads to stronger negative impacts of exploitation on work meaningfulness. In contrast, when employees have low performance reward expectancy, they do not have high expectations of their contributions being converted into material rewards. When suffering from exploitative leadership, subordinates are accustomed to and thus do not feel strongly about the loss of resources, thus weakening the influence of exploitation on work meaningfulness.

Hypothesis 4

Performance reward expectancy moderates the association between exploitative leadership and work meaningfulness such that high (vs. low) reward expectancy exacerbates (vs. dampens) the negative influence of exploitative leadership on work meaningfulness.

The fundamental idea of expectancy theory is reinforcement in which a future-focused positive expectancy (e.g., obtaining material rewards) leads employee resource investment in a certain direction (Eisenberger & Cameron, 1998). As mentioned above, in today’s business, performance reward expectancy is a strong motivator for employees to exert resources to perform well (Bartol & Srivastava, 2002; Prendergast, 1999). However, research on the outcomes of performance reward expectancy does not necessarily specify the content of performance-related behaviors in the ethical domain. Accumulated evidence about the performance-enhancing effect of reward expectancy occurs in the task performance domain. That is, employees with higher performance reward expectancy are motivated to exert more effort to enhance their task performance because doing so will give them access to ensuring the receipt of rewards (Han et al., 2015). This affects resource allocation such that employees are more likely to spend the valued and limited cognitive and attentional resources on areas directly related to successfully achieving their job tasks. Issues such as moral aspects of the workplace are typically not at the core of job tasks (Ren & Jackson, 2020; Ren et al., 2021). Therefore, a high level of performance reward expectancy means employees have fewer moral resources. When this occurs, it is more likely for employees of exploitative leaders to be vulnerable to loss of moral potency.

Hypothesis 5

Performance reward expectancy moderates the association between exploitative leadership and moral potency such that high (vs. low) reward expectancy exacerbates (vs. dampens) the negative influence of exploitative leadership on moral potency.

Overview of Studies

We progressively test hypotheses in two studies. Study 1 tests H1, H2 and H4 and demonstrates the mediation pathway via work meaningfulness. Building upon Study 1, Study 2 tests the full research model (i.e., Fig. 1) by adding the mediation pathway (i.e., H3 and H5) via moral potency. Also Study 2 provides a more rigorous test to the research model by adding additional control variables (i.e., abusive supervision, trust in supervisors, general silence) to examine whether exploitative leadership goes above and beyond what we already know about antecedents of general silence (Hao et al., 2022) to be associated with ethical silence in specific.

Study 1 Methods

Sample and Procedure

We test our hypotheses using data from a sample of employees and their supervisors in manufacturing and service enterprises located in an eastern province of China. Access to data collection was obtained from liaison with the HR managers through the professional network of one of the authors. We undertook three surveys at different points in time using a two-week interval between each survey to address common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012). First, in May 2021, we randomly selected 550 employees from the staff directories and sent them an invitation package, which explained the purpose of the project, the procedures used to protect their privacy, and an initial survey with questions related to their demographics, exploitative leadership and performance reward expectancy. The invitation letter also explained that they were free to exit the survey at any time. Of the 550 employees (from 110 teams), 463 responses (from 93 teams) were received by the cut off data; representing a response rate of 84%. Next, we sent a follow-up survey to the 463 employees which asked them to provide ratings on their work meaningfulness. We received completed surveys from 397 employees from 80 teams, a response rate of 86%. Lastly, with the support of the HR managers, we identified the supervisors (n = 80) of the 397 employees and sent a supervisor survey, asking them to evaluate the focal employees’ ethical silence. We received 73 completed surveys from the supervisors. Altogether, 351 completed employee surveys from 73 teams were used in the final data analysis, an overall response rate of 88%.

Among the 351 employees, 51.3% were men; 55.3% were unmarried; 22.2% were under 20 years old, 25.4% between 21 and 30 years old, 23.6% between 31 and 40 years old, and 28.8% over 41 years old; 22.8% had attended junior college, vocational education, or below, 28.2% were undergraduates, 24.8% were postgraduates, and 24.2% had received a doctoral education. 16.8% had tenure of less than 1 year, 23.6% between 1 and 3 years, 22.5% between 3 and 5 years, 23.1% between 5 and 7 years, and 14.0% over 7 years.

Measures

We initially developed questionnaires in English and then translated into Chinese using back translation techniques (Brislin, 1970). Unless otherwise stated, we use 5-point Likert-type scales to measure all items, with 1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree”.

Exploitative leadership was measured using the 15-item scale developed by Schmid et al. (2019). A sample item includes: “Uses our work for his or her personal gain.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92. The ICC (1) value was 0.43, ICC (2) value was 0.79, and the Rwg (reliability of score within group) value was 0.99.

Work meaningfulness was measured using the 3-item scale developed by Spreitzer (1995). A sample item includes: “The work I do is meaningful to me.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Ethical silence was measured using the 5-item scale developed by Tangirala and Ramanujam (2008) that are adapted specifically in the ethical domain. A sample item is: “Although he/she had ideas for improving ethical issues in his/her workgroup, he/she did not speak up.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Performance reward expectancy was measured using the 4-item scale developed by Eisenberger and Aselage (2009). A sample item is: “Good performance leads to higher pay.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91. The ICC (1) value was 0.36, ICC (2) value was 0.73, and the Rwg (reliability of score within group) value was 0.95.

Control variables We controlled for employee demographics, including gender (1 = women; 0 = men), age (3 = over 41 years old; 2 = 31–40 years old; 1 = 21–30 years old; 0 = under 20 years old), education (3 = PhD; 2 = postgraduate; 1 = undergraduate; 0 = junior college, vocational education or below) and tenure (4 = over 7 years; 3 = 5–7 years; 2 = 3–5 years; 1 = 1–3 years; 0 = under 1 year), and team size, which are typically included as control variables in prior research on exploitative leadership (e.g. Cheng et al., 2023; Syed et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b). These might influence how employees respond to exploitative leadership (Guo et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2015). We also controlled for employee marital status (1 = married; 0 = unmarried) because it may affect employees’ emotional function and workplace behaviors (Tang et al., 2017). We controlled for education level as people with higher education may have higher pursuits of work meaningfulness (Nehari & Bender, 1978).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, internal consistency reliability, and correlations of the study variables. We used Mplus8.3 to perform a multi-level confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA). The hypothesized four-factor model (exploitative leadership, work meaningfulness, ethical silence, and performance reward expectancy) fit the data well (χ2[226] = 310.34, χ2/df = 1.37, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, SRMR within = 0.04, SRMR between = 0.07). It is also a better fit than alternative models as summarized in Table 2.

Given the potential attribution of participants at different times, we followed Goodman and Blum’s (1996) recommended procedure which is also used in prior studies using similar multi-wave research design (e.g., Liu et al., 2010). Specifically, we undertook multiple logistic regressions by using survey time as the dependent variable and our study variables as the independent variable. Results showed that all logistic regression coefficients were not significant. In addition, we assessed mean differences in key variables across times. All t tests showed no significant mean differences. These results suggest that attrition did not pose a serious threat here.

Hypotheses Testing

We specified and tested a multilevel moderated-mediation model of the association between exploitative leadership and ethical silence via work meaningfulness contingent on performance rewards expectancy.

The results are summarized in Table 3. As shown, the direct influence of exploitative leadership on ethical silence behavior was (β = 0.37, se = 0.18, p < 0.05), supporting Hypothesis 1. Further, exploitative leadership was negatively related to work meaningfulness (β = − 0.50, se = 0.22, p < 0.05). In return, work meaningfulness was negatively related to ethical silence (β = − 0.34, se = 0.09, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2, which proposes a mediation relationship between exploitative leadership and ethical silence via work meaningfulness was further supported, with the significant indirect effect of 0.17 (se = 0.09, p < 0.05).

Then, our study tested the moderation effect of performance reward expectancy on the relationships between exploitative leadership and work meaningfulness (H4). As shown in Table 2, the interaction term was significant and negatively associated with work meaningfulness (β = − 1.31, se = 0.58, p < 0.05). Figure 2 depicts the nature of this interaction relationship. Specifically, with a high level of performance reward expectancy, the relationship between exploitative leadership and work meaningfulness was stronger (β = − 1.29, se = 0.36, p < 0.01) than that under a low level of performance reward expectancy (β = 0.29, se = 0.46, p = 0.53). The results supported Hypothesis 4. Additionally, the computed moderated mediation index (index = 0.45, p < 0.10, 95%CI [0.00, 0.89]) shows that performance reward expectancy significantly moderates the association between exploitative leadership and ethical silence via work meaningfulness.

Study 2 Methods

Sample and Procedure

In study 2, we build on Study 1 to test the full research model shown in Fig. 1 by adding the mediation pathway via moral potency. We obtained access to employees and their supervisors in firms that are business partners of a major Chinese university and collected data at three different points in time. Specifically, with the support of HR managers (or equivalent), we obtained the staff directories and randomly selected 200 work teams (involving 910 employees) from the staff directories. So at Time 1, we sent an invitation to these 910 employees, asking them to rate exploitative leadership, abusive supervision, trust in supervisor, leader-member exchange (LMX), and performance reward expectancy. We received 709 responses (142 teams), a response rate of 77.9%. Two weeks later, at Time 2, we sent a follow-up survey to the 709 employees, inviting them to provide ratings on their work meaningfulness and moral potency. We received completed surveys from 623 employees (from 124 teams), a response rate of 87.9%. Two weeks’ later, at Time 3, we contacted the supervisors (n = 124) of the 623 employees, asking them to evaluate the focal employees’ ethical silence and general silence, with 98 responses received. Altogether, 526 completed employee surveys from 98 teams were used in the final data analysis.

Among the 526 employees, 48.7% were men; 51.1% were not married; 20.3% were under 20 years old, 17.5% between 21 and 30 years old, 32.9% between 31 and 40 years old, and 29.3% over 41 years old; 26.2% had attended junior college, vocational education, or below, 35.7% were undergraduates, 19.2% were postgraduates, and 18.9% had received a doctoral education. 15.0% had tenure of less than 1 year, 24.7% between 1 and 3 years, 18.8% between 3 and 5 years, 26.0% between 5 and 7 years, and 15.5% over 7 years.

Measures

We used the same scales to measure exploitative leadership (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91, ICC (1) = 0.39, ICC (2) = 0.77, Rwg = 0.99), work meaningfulness (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86), ethical silence (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87), performance reward expectancy (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89, ICC (1) = 0.25, ICC (2) = 0.64, Rwg = 0.95), and demographics (gender, age, education, marital status). We measured moral potency by using the 3-item scale developed by Hannah and Avolio (2010), including “I will assume responsibility and take action when I see an unethical act”, “I will confront my peers if they commit an unethical act” and “I am confident that I can determine what needs to be done when I face ethical dilemmas”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80.

Control Variables To provide a more stringent test of our hypotheses, we controlled for a number of variables. Specifically, we controlled for abusive supervision, trust in supervisors and LMX as they are reported to be relevant to general silence in a recent meta-analysis (Hao et al., 2022). Abusive supervision was measured by the 5-item scale developed by Tepper (2000). A sample item is: “my boss puts me down in front of others”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90. Trust in supervisors was measured by the 5-item scale developed by Mayer and Gavin (2005). A sample item is: “I would be comfortable giving my supervisor a task or problem that was critical to me, even if I could not monitor his/her actions”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90. LMX (Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86) was measured by the 7-item scale by Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995). We also added general silence as the additional dependent variable to test how exploitative leadership associates with ethical silence above and beyond its impact on general silence. General silence was measured by Tangirala and Ramanujam’s (2008) 5-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Table 4 shows Study 2’s descriptive statistics. As in Study 1, we also used Mplus8.3 to perform MCFA, which showed that the hypothesized nine-factor model fit the data better (χ2[306] = 394.11, χ2/df = 1.29, RMSEA = 0.02, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR within = 0.03, SRMR between = 0.08) than alternative models (Table 5).

In addition, we took the similar approach as in Study 1 to assess the potential attrition bias. The logistic regression coefficients in which survey time was the dependent variable and study variables as the independent variable were insignificant. Also all t-tests performance showed no significant differences in means for variables across time. Altogether, the results suggest attrition should not be a concern here.

Hypotheses Testing

The results are summarized in Table 6. First, we tested the direct association between exploitative leadership and ethical silence (β = 0.50, se = 0.08, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1. Then, we tested the indirect effect enabled by the two proposed mediations. As shown in Table 6, exploitative leadership was negatively related to work meaningfulness (β = − 0.66, se = 0.23, p < 0.01). In return, work meaningfulness was negatively related to ethical silence (β = − 0.30, se = 0.09, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2, which proposes a mediation relationship between exploitative leadership and ethical silence via work meaningfulness was supported, with the significant indirect effect of 0.20 (se = 0.10, p < 0.05). Besides, exploitative leadership was negatively related to moral potency (β = − 0.56, se = 0.15, p < 0.01). In return, moral potency was negatively related to ethical silence (β = − 0.50, se = 0.15, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 3, which proposes a mediation relationship between exploitative leadership and ethical silence via moral potency was also supported (indirect effect = 0.28, se = 0.12, p < 0.05).

Next, our study tested the moderation effect of performance reward expectancy on the relationships between exploitative leadership and work meaningfulness (H4). As shown in Table 6, the interaction term was significant and negatively associated with work meaningfulness (β = − 0.86, se = 0.36, p < 0.05), with the nature of this interaction relationship depicted in Fig. 3. Therefore, H4 was supported. The interaction term between exploitative leadership and performance reward expectancy on moral potency was significant (β = − 0.78, se = 0.28, p < 0.01) and Fig. 4 depicts the nature of this interaction relationship. Altogether Hypothesis 5 was supported. We further computed the indices of moderated mediation via work meaningfulness (index = 0.24, se = 0.12, p < 0.05) and moral potency (index = 0.37, se = 0.16, p < 0.05). The results show that both work meaningfulness and moral potency played significant roles in mediating the exploitative leadership-ethical silence association, contingent upon performance reward expectancy.

Discussion

Theoretical Implications

This study extends the literature on employee silence by specifying the content of silence in relation to ethical issues in business. Our findings show that exploitative leadership can contribute to ethical silence above and beyond general silence, even after controlling for abusive supervision and trust in supervisors. Although evidence and anecdotes abound about the detriments of business scandals to the reputation and survival of corporates, remaining silent on ethical issues continues to be pervasive strategy employees use (Walsh, 2021). Exploring the ethical content of employee silence, therefore, is a meaningful endeavor, as knowledge of its antecedents helps to identify factors that contribute to its occurrence. Employee ethical silence not only involves the evaluation of risks/harms to the self, i.e. the behavioral inhabitation system currently assumed in the general employee silence literature (Sherf et al., 2021). Also, it involves the evaluation of ethicality of the job or organization-related factors and the potential harm due to communication about those ethical issues. So studying employee ethical silence helps to advance the silence literature to emphasize the behavioral inhabitation system specifically in the context of ethical dilemmas.

Second, the study enables a fuller understanding of the underlying mechanisms through which exploitative leadership associates with ethical silence. The existing silence literature has studied the direct link of abusive supervision (Lam & Xu, 2019; Wang et al., 2020), empowering leadership (Hassan et al., 2019) with employee silence, without necessarily exploring the mediation pathways. Of the limited research on the mediation to explain the association, they typically draw from the behavioral inhibition system to focus on psychological safety (Duan et al., 2018), emotional exhaustion (Xu et al., 2015), or leader trustworthiness (Hamstra et al., 2021). By utilizing the COR theory and insights from the behavioral ethics literature (e.g., Hannah et al., 2011), we help to consolidate a range of potential resource processes that are at play as a result of exploitative leadership. In this regard, it helps to contribute to the growing literature on exploitative leadership by responding to the research call concerning how it can influence a broader range of employee psychological and behavioral outcomes (Schmid et al., 2019).

For instance, research so far has revealed the influence of exploitative leadership on reduced affective commitment and job satisfaction, increasing work deviance and burnout (Schmid et al., 2019), innovative behavior (Wang et al., 2021b) and knowledge sharing (Guo et al., 2021). However, to the best of our knowledge, the impact of leaders’ exploitation on ethical silence, an ethics-specific type of a widespread workplace phenomenon (silence), has been overlooked. Therefore, our research broadens the range of the existing exploitative leadership literature and responds to the call of Schmid et al. (2019) for more empirical research to shed new light on exploitative leadership. Our research enriches this knowledge by showing exploitative leadership is a debilitating form of leader behavior that is conducive to ethical silence.

In addition, this study contributes to the exploitative leadership literature by theorizing and testing the underlying mechanisms that transform exploitative leadership into employee silence linkage. Drawing from the perspective of COR theory, it demonstrates the mediating role of work meaningfulness and moral potency. Researchers have demonstrated the direct impact of exploitative leadership on job satisfaction, thriving at work, and relational attachment (Schmid et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021a, 2021b). According to COR theory, our study introduces two resource-related pathways in the relationship between exploitative leadership and ethical silence. Our findings show that leaders’ exploitation reduces employee work meaningfulness (as a typical form of cognitive resources) and moral potency (as a typical form of moral resources), and thus led to ethical silence behavior. Our finding contributes to explicating the “black box” that links leaders’ exploitation to employee silence and broadens our understanding of how dark-side leadership influences employees’ behavior specifically in the ethical domain (Schmid et al., 2019).

Prior research on exploitative leadership has tapped into specific mechanisms in isolation, for instance leader-member exchange (Syed et al., 2021), emotional exhaustion (Wang et al., 2021b), psychological distress (Guo et al., 2021), using the lens of social exchange theory (Wu et al., 2021), social cognitive theory (Cheng et al., 2023) and stress-related theories (e.g., Elsaied, 2022; Guo et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b). Collectively they point to the importance of resources in the process through which employees interpret and respond to exploitative leadership and suggest that exploitative leadership negatively impacts employees’ valuable resources. However, the current literature has not yet tapped into multiple resources that are essential to constituting employees’ organizational life for their ethical silence. On one hand, our results show that the exploitation of others by leaders is undertaken in the work context, which impacts employees’ attitudes towards the work as a resultant of exploitative leadership. On the other hand, our results show that moral potency, as a subjective experience of efficacy specifically related to ethical issues, represents another important yet under-specified mechanism in exploitative leadership research.

Furthermore, we contribute to exploitative leadership research with a more nuanced understanding of how its implications occur. By demonstrating the moderating role of performance reward expectancy, our research reveals the boundary conditions that leaders’ exploitation is more or less harmful to employees’ internal resources and behaviors. Although recent years have witnessed increasing interests in exploring the influence of exploitative leadership (Schmid et al., 2019), the boundary conditions of exploitative leadership are not well developed theoretically. To address this gap, we draw from COR theory to position performance reward expectancy as an important contingency factor underlying the association between exploitative leadership and employee silence via work meaningfulness and moral potency. Therefore, our study responds to the call for paying greater attention to the role of individual factor in the relationship between dark-side leadership and subordinates’ behavior (Yao et al., 2020).

Practical Implications

Our findings suggest that organizations need to take measures to prevent, monitor, and reduce leaders’ exploitation due to its debilitating effects on employees. For example, organizations could develop human resource management systems such as recruitment, promotion, performance and reward systems to identify and recognize leaders with low levels of selfish tendencies. Such systems should ensure that they capture unconscious bias in relation to exploitative behaviors (Schmid et al., 2019). We further recommend that organizations adopt a zero-tolerance policy for leaders’ exploitation and link managerial performance and compensation systems to a “no exploitation” policy. Managers need to be trained of the pervasiveness and detriments of employee ethical silence. At the same time, when feedback is obtained regarding leaders’ exploitative behaviors, organizations need to respond quickly, taking measures to protect subordinates and resolving problems fairly in a timely manner.

We also recommend organizations pay attention to the important role of work meaningfulness and moral potency in reducing employee ethical silence. Research shows that subordinates become more attached to their organization and work more actively when they have stronger work meaningfulness (Kwan et al., 2018). Therefore, we suggest that organizations promote work meaningfulness by offering employees the opportunity to realize their potential at work, for instance via job design. In addition, our study suggests that organizations would conduct regular surveys to assess the degree to which subordinates perceive their work to be meaningful and their efficacious beliefs related to ethical issues. Relatedly, organizations could proactively focus on both personal and contextual factors to enrich the meaning employees derive from work. In addition, a range of policies and support systems are recommended to be in place to strengthen employees’ moral potency. For instance, organizations should involve employees in planning activities related to business ethics, hold them accountable, delegate authority and encourage them to identify and solve ethical dilemmas, and acknowledge those who speak up.

In addition, we advise organizations to create an organizational culture of fairness, which allows employees to perceive the possibility of achieving their reward expectancy. Senior managers should serve as a role model to leaders in conforming to organizational regulations, which helps to augment the trust of employees in their performance-based rewards. Further, organizations should establish an effective performance reward mechanism, objectively evaluate employees’ work contributions, give corresponding rewards on time, and effectively stimulate employees’ work meaningfulness.

Limitations and Future Research Prospects

Like most research, our study has several limitations that need to be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings. First our data for hypothesis testing is from one province in China. Given the heterogeneity of China’s economic, social, and cultural development across regions, we acknowledge the possibility of overlooking institutional factors prevalent in other regions that might influence leaders and employee behaviors. Therefore, future research could expand the sample size across different institutional contexts. Second, although the data were collected at different points in time to reduce common method bias in both studies, we caution against making causality claims. Therefore, longitudinal or experimental designs would be beneficial to test causal relationships in future research. Third, we note that LMX and trust in leader were not significantly correlated with ethical silence. This may appear to be inconsistent with the meta-analysis reported by Hao et al. (2022). One potential explanation is that Hao et al.’s (2022) work does not focus specifically on employee silence in the ethical domain. It is possible that the high-quality relationship (i.e., LMX) and trust employees experience with supervisors are more influential in shaping attitudes and bheaviors related to core tasks, rather than ethical issues. Nonetheless, this represents an interesting opportunity for future research to further take a fine-grained approach in investigating different types of silence. Last but not least, when exploring the boundary conditions of the studied relationships, we only examined the moderating role of performance reward expectancy. Further research could consider other individual (e.g., self-evaluation) or situational (e.g., competition climate) factors as moderators of the impact of exploitative leadership on ethical silence.

Conclusions

This research has focused on ethical silence, a domain-specific silence behavior that business ethics research has largely overlooked to date. Based on COR theory, we developed and tested a theoretical framework to explain how and when exploitative leadership associates with ethical silence. Our research provides new theoretical and empirical insights on the debilitating effects of exploitative leadership on ethical silence via work meaningfulness and moral potency, contingent upon performance reward expectancy. Our findings add to the small but growing literature on the debilitating effects of exploitative leadership and suggest that organizations should strive to ‘weed out’ leaders with exploitative tendencies so as to circumvent ethical silence among employees and strengthen ethical behavior.

References

Anteby, M., & Anderson, C. (2016). Management and morality/ethics—The elusive corporate morals. In Oxford Handbook of Management (pp. 386–398).

Bailey, C., & Madden, A. (2016). What makes work meaningful—or meaningless. MIT Sloan Management Review, 57(4), 1–9.

Baker, D. S., & Delpechitre, D. (2013). Collectivistic and individualistic performance expectancy in the utilization of sales automation technology in an international field sales setting. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 33(3), 277–288.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Bartol, K. M., & Srivastava, A. (2002). Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward systems. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 9(1), 64–76.

Bolton, L. R., Harvey, R. D., Grawitch, M. J., & Barber, L. K. (2012). Counterproductive work behaviours in response to emotional exhaustion: A moderated mediational approach. Stress and Health, 28(3), 222–233.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216.

Cadsby, C. B., Song, F., & Tapon, F. (2007). Sorting and incentive effects of pay for performance: An experimental investigation. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 387–405.

Calabretta, G., Durisin, B., & Ogliengo, M. (2011). Uncovering the intellectual structure of research in business ethics: A journey through the history, the classics, and the pillars of journal of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(4), 499–524.

Cheng, K., Guo, L., & Luo, J. (2023). The more you exploit, the more expedient I will be: A moral disengagement and Chinese traditionality examination of exploitative leadership and employee expediency. Asia Pacific Journal of Management., 40(3), 151–167.

Chou, S. Y., & Chang, T. (2020). Employee silence and silence antecedents: A theoretical classification. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(3), 401–426.

De Boeck, G., Dries, N., & Tierens, H. (2019). The experience of untapped potential: Towards a subjective temporal understanding of work meaningfulness. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 529–557.

Duan, J. Y., Bao, C. Z., Huang, C. Y., & Brinsfield, C. T. (2018). Authoritarian leadership and employee silence in China. Journal of Management and Organization, 24(1), 62–80.

Dyne, L. V., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392.

Eisenberger, R., & Aselage, J. (2009). Incremental effects of reward on experienced performance pressure: Positive outcomes for intrinsic interest and creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(1), 95–117.

Eisenberger, R., & Cameron, J. (1998). Reward, intrinsic interest, and creativity: New findings. American Psychologist, 53(6), 676–679.

Elsaied, M. (2022). Exploitative leadership and organizational cynicism: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 43(1), 25–38.

Feldman, D. B., Davidson, O. B., & Margalit, M. (2015). Personal resources, hope, and achievement among college students: The conservation of resources perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(3), 543–560.

Fortune. (2020). The biggest business scandals of 2020. Retrieved from https://fortune.com/2020/12/27/biggest-business-scandals-of-2020-nikola-wirecard-luckin-coffee-twitter-security-hack-tesla-spx-mcdonalds-ceo-ppp-fraud-wells-fargo-ebay-carlos-ghosn/

Frankort, H. T., & Avgoustaki, A. (2022). Beyond reward expectancy: How do periodic incentive payments influence the temporal dynamics of performance? Journal of Management, 48(7), 2075–2107.

Garbers, Y., & Konradt, U. (2014). The effect of financial incentives on performance: A quantitative review of individual and team-based financial incentives. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 102–137.

Gerpott, F. H., & Van Quaquebeke, N. (2022). Kiss-up-kick-down to get ahead: A resource perspective on how, when, why, and with whom middle managers use ingratiatory and exploitative behaviours to advance their careers. Journal of Management Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12855

Goodman, J. S., & Blum, T. C. (1996). Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. Journal of Management, 22(4), 627–652.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., & Eissa, G. (2012). Bottom-line mentality as an antecedent of social undermining and the moderating roles of core self-evaluations and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 343–359.

Greenberg, J., & Edwards, M. S. (2009). Voice and silence in organizations. Emerald Group Publishing.

Guo, L. M., Cheng, K., & Luo, J. L. (2021). The effect of exploitative leadership on knowledge hiding: A conservation of resources perspective. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 42(1), 83–98.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279.

Haines, V. Y. I., & Taggar, S. (2006). Antecedents of team reward attitude. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 10(3), 194–205.

Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364.

Hamstra, M. R. W., Schreurs, B., Jawahar, I. M., Laurijssen, L. M., & Hunermund, P. (2021). Manager narcissism and employee silence: A socio-analytic theory perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(1), 29–54.

Han, J. H., Bartol, K. M., & Kim, S. (2015). Tightening up the performance-pay linkage: Roles of contingent reward leadership and profit-sharing in the cross-level influence of individual pay-for-performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 417–430.

Hannah, S. T., & Avolio, B. J. (2010). Moral potency: Building the capacity for character-based leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 62(4), 291–310.

Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & May, D. R. (2011). Moral maturation and moral conation: A capacity approach to explaining moral thought and action. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 663–685.

Hao, L. L., Zhu, H., He, Y. Q., Duan, J. Y., Zhao, T., & Meng, H. (2022). When is silence golden? A meta-analysis on antecedents and outcomes of employee silence. Journal of Business and Psychology, 37(5), 1039–1063.

Hassan, S., DeHart-Davis, L., & Jiang, Z. N. (2019). How empowering leadership reduces employee silence in public organizations. Public Administration, 97(1), 116–131.

Hirschi, A. (2012). Callings and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of work meaningfulness, occupational identity, and occupational self-efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(3), 479–485.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 116–122.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128.

Hobfoll, S. E., Vinokur, A. D., Pierce, P. F., & Lewandowski-Romps, L. (2012). The combined stress of family life, work, and war in Air Force men and women: A test of conservation of resources theory. International Journal of Stress Management, 19(3), 217–237.

Humphrey, S. E., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1332–1356.

Kiewitz, C., Restubog, S. L. D., Shoss, M. K., Garcia, P., & Tang, R. L. (2016). Suffering in silence: Investigating the role of fear in the relationship between abusive supervision and defensive silence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(5), 731–742.

Kruglanski, A. W. (1996). Goals as knowledge structures. Guilford Press.

Kwan, H. K., Zhang, X., Liu, J., & Lee, C. (2018). Workplace ostracism and employee creativity: An integrative approach incorporating pragmatic and engagement roles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(12), 1358–1366.

Lam, L. W., & Xu, A. J. (2019). Power imbalance and employee silence: The role of abusive leadership, power distance orientation, and perceived organisational politics. Applied Psychology, 68(3), 513–546.

Lawler, E. E., III. (1973). Motivation in work organizations. Brooks/Cole.

Lee, M. C. C., Idris, M. A., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2017). The linkages between hierarchical culture and empowering leadership and their effects on employees’ work engagement: Work meaningfulness as a mediator. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(4), 392–415.

Lepisto, D. A., & Pratt, M. G. (2017). Meaningful work as realization and justification: Toward a dual conceptualization. Organizational Psychology Review, 7(2), 99–121.

Leunissen, J. M., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Cohen, T. R. (2018). Organizational nostalgia lowers turnover intentions by increasing work meaning: The moderating role of burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 44–57.

Levine, M. P., & Boaks, J. (2014). What does ethics have to do with leadership? Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 225–242.

Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., Wu, L.-Z., & Wu, W. (2010). Abusive supervision and subordinate supervisor-directed deviance: The moderating role of traditional values and the mediating role of revenge cognitions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 835–856.

Lyu, Y. J., Wu, L. Z., Ye, Y. J., Kwan, H. K., & Chen, Y. Y. (2022). Rebellion under exploitation: How and when exploitative leadership evokes employees’ workplace deviance. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05207-w

Majeed, M., & Fatima, T. (2020). Impact of exploitative leadership on psychological distress: A study of nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1713–1724.

Mayer, R. C., & Gavin, M. B. (2005). Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 874–888.

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412.

Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., & Pan, C. (2015). An approach-inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547–580.

Mukherjee, A. S. (2016). Why we’re seeing so many corporate scandals. Harvard Business Review, 12, 2–5.

Nehari, M., & Bender, H. (1978). Meaningfulness of a learning experience: A measure for educational outcomes in higher education. Higher Education, 7(1), 1–11.

Park, C., & Keil, M. (2009). Organizational silence and whistle-blowing on IT projects: An integrated model. Decision Sciences, 40(4), 901–918.

Parker, S. L., Jimmieson, N. L., & Techakesari, P. (2017). Using stress and resource theories to examine the incentive effects of a performance-based extrinsic reward. Human Performance, 30(4), 169–192.

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., & Podsakoff, N. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

Prendergast, C. (1999). The provision of incentives in firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 37(1), 7–63.

Ren, S., & Jackson, S. E. (2020). HRM institutional entrepreneurship for sustainable business organizations. Human Resource Management Review, 30(3), 100691.

Ren, S., Tang, G. Y., & Jackson, S. E. (2021). Effects of green HRM and CEO ethical leadership on organizations’ environmental performance. International Journal of Manpower, 42(6), 961–983.

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127.

Schmid, E. A., Verdorfer, A. P., & Peus, C. V. (2018). Different shades-different effects? Consequences of different types of destructive leadership. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1289), 1–16.

Schmid, E. A., Verdorfer, A. P., & Peus, C. (2019). Shedding light on leaders’ self-interest: Theory and measurement of exploitative leadership. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1401–1433.

Schnell, T., Höge, T., & Pollet, E. (2013). Predicting meaning in work: Theory, data, implications. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(6), 543–554.

Sherf, E. N., Parke, M. R., & Isaakyan, S. (2021). Distinguishing voice and silence at work: Unique relationships with perceived impact, psychological safety, and burnout. Academy of Management Journal, 64(1), 114–148.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Sonenshein, S. (2007). The role of construction, intuition, and justification in responding to ethical issues at work: The sensemaking-intuition model. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1022–1040.

Song, B. H., Qian, J., Wang, B., Yang, M. L., & Zhai, A. R. (2017). Are you hiding from your boss? Leader’s destructive personality and employee silence. Social Behavior and Personality, 45(7), 1167–1174.

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465.

Stein, M. K., Wagner, E. L., Tierney, P., Newell, S., & Galliers, R. D. (2019). Datification and the pursuit of meaningfulness in work. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 685–717.

Stouten, J., & Tripp, T. M. (2009). Claiming more than equality: Should leaders ask for forgiveness? Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 287–298.

Sun, Z. Z., Wu, L. Z., Ye, Y. J., & Kwan, H. W. (2023). The impact of exploitative leadership on hospitality employees’ proactive customer service performance: A self-determination perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(1), 46–63.

Sungu, L. J., Weng, Q., Hu, E., Kitule, J. A., & Fang, Q. (2020). How does organizational commitment relate to job performance? A conservation of resource perspective. Human Performance, 33(1), 52–69.

Syed, F., Naseer, S., Akhtar, M. W., Husnain, M., & Kashif, M. (2021). Frogs in boiling water: A moderated-mediation model of exploitative leadership, fear of negative evaluation and knowledge hiding behaviors. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(8), 2067–2087.

Tang, Y., Huang, X., & Wang, Y. (2017). Good marriage at home, creativity at work: Family–work enrichment effect on workplace creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(5), 749–766.

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 61(1), 37–68.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190.

Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 601–617.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York Press.

Wabba, M. A., & House, R. J. (1974). Expectancy theory in work and motivation: Some logical and methodological issues. Human Relations, 27(2), 121–147.

Walsh, N. (2021). How to encourage employees to speak up when they see wrongdoing. Harvard Business Review.

Wang, C. C., Hsieh, H. H., & Wang, Y. D. (2020). Abusive supervision and employee engagement and satisfaction: The mediating role of employee silence. Personnel Review, 49(9), 1845–1858.

Wang, Z. N., Chen, Y. H., Ren, S., Collins, N., Cai, S. H., & Rowley, C. (2021a). Exploitative leadership and employee innovative behaviour in China: A moderated mediation framework. Asia Pacific Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2021.1990588

Wang, Z. N., Sun, C. W., & Cai, S. H. (2021b). How exploitative leadership influences employee innovative behavior: The mediating role of relational attachment and moderating role of high-performance work systems. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 42(2), 233–248.

Wang, Z., & Xu, H. Y. (2019). When and for whom ethical leadership is more effective in eliciting work meaningfulness and positive attitudes: The moderating roles of core self-evaluation and perceived organizational support. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(4), 919–940.

Webster, V., & Brough, P. (2021). Destructive leadership in the workplace and its consequences: Translating theory and research into evidence-based practice. Sage.

Wei, H. L., Shan, D. L., Wang, L., & Zhu, S. Y. (2022). Research on the mechanism of leader aggressive humor on employee silence: A conditional process model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 135, 1–12.

Wu, L.-Z., Sun, Z., Ye, Y., Kwan, H. K., & Yang, M. (2021). The impact of exploitative leadership on frontline hospitality employees’ service performance: A social exchange perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 96(2021), 1–10.

Wu, X., Kwan, H. K., Ma, Y., Lai, G., & Yim, F.H.-K. (2020). Lone wolves reciprocate less deviance: A moral identity model of abusive supervision. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(7), 859–885.

Xu, A. J., Loi, R., & Lam, L. W. (2015). The bad boss takes it all: How abusive supervision and leader-member exchange interact to influence employee silence. Leadership Quarterly, 26(5), 763–774.

Yao, Z., Zhang, X. C., Luo, J. L., & Huang, H. (2020). Offense is the best defense: The impact of workplace bullying on knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(3), 675–695.

Ye, Y., Chen, M., Wu, L. Z., & Kwan, H. K. (2023). Why do they slack off in teamwork? Understanding frontline hospitality employees’ social loafing when faced with exploitative leadership. International Journal of Hospitality Management., 109, 103420.

Ye, Y., Lyu, Y., Wu, L. Z., & Kwan, H. K. (2022). Exploitative leadership and service sabotage. Annals of Tourism Research., 95, 103444.

Zeng, W., Zhou, Y., & Shen, Z. Y. (2018). Dealing with an abusive boss in China: The moderating effect of promotion focus on reward expectancy and organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Conflict Management, 29(4), 500–518.

Acknowledgements

This research is partly supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72271231)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This study has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study has compliance with ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Ren, S., Chadee, D. et al. Employee Ethical Silence Under Exploitative Leadership: The Roles of Work Meaningfulness and Moral Potency. J Bus Ethics 190, 59–76 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05405-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05405-0