Abstract

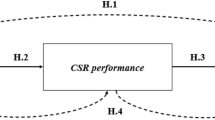

The goal of this paper was to investigate whether and how a firm that engages in different kinds of corporate social performance (CSP) can create a favorable corporate reputation among its stakeholders, and as a result achieve a good financial performance. Building on stakeholder theory, we distinguish two types of reputation—reputation among public stakeholders and reputation among financial stakeholders. We argue that CSP activities affect these two reputations differently. In addition, we empirically test the relationship among different types of CSP, reputation among public and financial stakeholders, and financial performance. Our results suggest that (1) Carroll’s four types of CSP (i.e., economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic) affect financial performance differently, and (2) their effects are mediated by reputation among public and financial stakeholders. Our findings provide guidelines for managers on choosing to emphasize certain CSP aspects in their communication, depending on the specific stakeholder group they are targeting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We follow Rao et al. (2004) to compute Tobin’s q as (share price × number of common stock outstanding + liquidating value of the firm’s preferred stock + short-term liabilities − short-term assets + book value of long-term debt)/book value of total assets.

Size is constructed as the logarithm of Total Assets. We follow Agarwal and Berens (2009) in measuring leverage as Total Debt/Total Assets. Capital Intensity was measured by Net Fixed Assets/Total Assets.

Size has been suggested to be a factor that affects both corporate reputation and firm performance (Hillman and Keim 2001; Roberts and Dowling 2002). Leverage is identified as a factor that can account for differences in CFP across firms (Waddock and Graves 1997). In addition, Capon et al. (1990) argue that capital intensity has a negative effect on firm’s financial performance.

For the PLS algorithm, we used the following settings: path weighting scheme, standardized indicators, maximum 300 iterations, stop criterion <10−5, and initial weights 1.0. For the bootstrapping, we used the following settings: construct level sign changes, and 5,000 resamples of 231 cases.

The calculation of GLB is based on the software FACTOR. See, http://psico.fcep.urv.es/utilitats/factor/index.html.

The results are available upon request.

The f² are calculated as the squared partial correlation between the dependent variable and a predictor (controlling for the other predictors in the model), divided by 1 minus the same squared partial correlation, as described by Cohen (1988).

The VAF is calculated as \((R_{1,i}^{2} \times R_{y,1}^{2} )/(R_{1,i}^{2} \times R_{y,1}^{2} + R_{2,i}^{2} \times R_{y,2}^{2} + R_{y,i}^{2} )\), where \(R_{1,i}^{2}\) (\(R_{2,i}^{2}\)) is the partial \(R^{2}\) of the CSP construct i when regressing the public (financial) reputation on all CSP constructs and control variables, \(R_{y,1}^{2}\) (\(R_{y,2}^{2}\)) is the partial \(R^{2}\) of the public (financial) reputation when regressing the financial performance on all constructs, \(R_{y,i}^{2}\) is the partial \(R^{2}\) of the CSP construct i when regressing the financial performance on all constructs, and i varies across the six CSP constructs. Note that the term \(R_{1,i}^{2} \times R_{y,1}^{2}\) is the explained variance measure \(R_{4.6}^{2}\) in formula 14 by Preacher and Kelley (2011).

References

Agarwal, M. K., & Berens, G. (2009). How corporate social performance influences financial performance: Cash flow and cost of capital. MSI Working Paper Series, 1(09-001), 3–26.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1991). Predicting the performance of measures in a confirmatory factor analysis with a pretest assessment of their substantive validities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(5), 732–740.

Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A., & Hatfield, J. D. (1985). An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 28(2), 446–463.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94.

Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2(2), 285–309.

Barney, J. B. (1992). Integrating organizational behavior and strategy formulation research: A resource based analysis. Advances in strategic management, 8(1), 39–61.

Bird, R., Hall, A. D., Momente, F., & Reggiani, F. (2007). What corporate social responsibility activities are valued by the market? Journal of Business Ethics, 76, 189–206.

Birkinshaw, J., Morrison, A., & Hulland, J. (1995). Structural and competitive determinants of a global integration strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 16(8), 637–655.

Boyd, B., Bergh, D., & Ketchen, D. (2010). Reconsidering the reputation-performance relationship: A resource-based view. Journal of Management, 36, 588–609.

Brammer, S. J., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 435–455.

Breusch, T. S., & Pagan, A. R. (1979). A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 47(5), 1287–1294.

Brown, B. (1997). Stock market valuation of reputation for corporate social performance. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(1), 76–80.

Brown, B., & Perry, S. (1994). Removing the financial performance halo from fortune’s most admired companies. Academy of Management Journal, 37(5), 1347–1359.

Buchholtz, A. K., Lubatkin, M., & O’Neill, H. M. (1999). Seller responsiveness to the need to divest. Journal of Management, 25(5), 633–652.

Capon, N., Farley, J. U., & Hoening, S. (1990). Determinants of financial performance: A meta-analysis. Management Science, 36, 1143–1159.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 4, 497–505.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizon, 34(4), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business and Society, 38(2), 268–296.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern methods for business research 295(2), 295–336.

Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Deephouse, D. L. (1997). The effect of financial and media reputations on performance. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(1,2), 68–71.

Deephouse, D. L. (2000). Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. Journal of Management, 26(6), 1091–1112.

Deephouse, D. L., & Carter, S. M. (2005). An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. Journal of Management Studies, 42(2), 329–360.

Deutsch, Y., & Ross, T. W. (2003). You are known by the directors you keep: Reputable directors as a signaling mechanism for young firms. Management Science, 49(8), 1003–1017.

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management science, 35(12), 1504–1511.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. (1995). The stakeholder theory of corporation: Concept, evidence and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20, 65–91.

Elsayed, K., & Paton, D. (2005). The impact of environmental performance on firm performance: Static and dynamic panel data evidence. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 16, 395–412.

Fan, X., Thompson, B., & Wang, L. (1999). Effects of sample size, estimation methods, and model specification on structural equation modeling fit indexes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 56–83.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name—Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

Fornell, C., & Bookstein, F. (1982). Two structural equations models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 440–452.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, September 13,122–126.

Fryxell, G. E., & Wang, J. (1994). The fortune corporate reputation index—Reputation for what? Journal of Management, 20(1), 1–14.

Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53, 51–71.

Greening, D. W., & Turban, D. B. (2000). Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Business and Society, 39(3), 254–280.

Griffin, J., & Mahon, J. (1997). The corporate social performance and corporate financial performance debate. Business and Society, 36, 5–31.

Handelman, J. M., & Arnold, S. J. (1999). The role of marketing actions with a social dimension: Appeals to the institutional environment. The Journal of Marketing, 33–48.

Handelman, J. M., & Arnold, S. J. (1999). The role of marketing actions with a social dimension: Appeals to the institutional environment. The Journal of Marketing, 33-48. Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. T., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS–SEM). Beverley Hills, CA: SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS–SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–151.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2012a). Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 312–319.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Pieper, T. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2012b). Applications of partial least squares path modeling in management journals: A review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 320–340.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012c). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433.

Halme, M., & Laurila, J. (2009). Philanthropy, integration or innovation? Exploring the financial and societal outcomes of different types of corporate responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(3), 325–339.

Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31, 405–440.

Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., et al. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about partial least squares: Comments on Rönkkö & Evermann (2013). Organizational Research Methods, 17(2), 182–209.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), Advances in international marketing (pp. 277–320). Bingley: Emerald.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22, 125–139.

Houston, M., & Johnson, S. (2000). Buyer-supplier contracts versus joint ventures: Determinants and consequences of transaction structure. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(February), 1–15.

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204.

Jensen, M. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76, 323–339.

Jensen, M. (2002). Value maximization, stakeholder theory, and the corporate objective function. Business Ethics Quarterly, 12, 235–256.

Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Research & Analytics. (2006). Getting started with KLD stats and KLD’s ratings definitions. Boston: Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Research & Analytics.

Koenker, R. (1981). A note on studentizing a test for heteroscedasticity. Journal of Econometrics, 17(1), 107–112.

Kourula, A., & Halme, M. (2008). Types of corporate responsibility and engagement with NGOs: An exploration of business and societal outcomes. Corporate Governance, 8(4), 557–570.

Lange, D., Lee, P., & Dai, Y. (2011). Organizational reputation: A review. Journal of Management, 37(1), 153–184.

Lohmöller, J.-B. (1989). Latent variable path modeling with partial least squares. Heidelberg: Physica.

Love, E. G., & Kraatz, M. (2009). Character, conformity, or the bottom line? How and why downsizing affected corporate reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 52(2), 314–335.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70, 1–18.

MacMillan, K., Money, K., & Downing, S. (2002). Best and worst corporate reputations—Nominations by the general public. Corporate Reputation Review, 4(4), 374–384.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2003). Nature of corporate responsibilities: Perspectives from American, French, and German consumers. Journal of Business Research, 56, 55–67.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(1), 3–19.

Maignan, I., & Ralston, D. A. (2002). Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the U.S.: Insights from businesses’ self-presentations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3), 497–514.

Margolis, J. D., & Walsh, J. P. (2003). Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48, 268–305.

Mattingly, J. E., & Berman, S. L. (2006). Measurement of corporate social action discovering taxonomy in the Kinder Lydenburg Domini ratings data. Business and Society, 45(1), 20–46.

Mazzola, P., Ravasi, D., & Gabbioneta, C. (2006). How to build reputation in financial markets. Long Range Planning, 39(4), 385–407.

McGuire, J. B., Schneeweis, T., & Branch, B. (1990). Perceptions of firm quality—A cause or result of firm performance? Journal of Management, 16(1), 167–180.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (1997). The role of money managers in assessing corporate social responsibility research. Journal of Investing, 6(4), 98–107.

Orlitzky, M. (2006). Links between corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: Theoretical and empirical determinants. In J. Allouche (Ed.), Corporate social responsibility vol. 2: Performances and stakeholders (pp. 41–64). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403–441.

Pfarrer, M. D., Pollock, T. G., & Rindova, V. P. (2010). A tale of two assets: The effects of firm reputation and celebrity on earnings surprises and investors’ reactions. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5), 1131–1152.

Ponzi, L. J., Fombrun, C. J., & Gardberg, N. A. (2011). RepTrak™ Pulse: Conceptualizing and validating a short-form measure of corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 14, 15–35.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16(2), 93–115.

Rao, V., Agarwal, M. K., & Dahlhoff, D. (2004). How is the manifest branding strategy related to the intangible value of a corporation? Journal of Marketing, 68(October), 126–141.

Reinartz, W., Haenlein, M., & Henseler, J. (2009). An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26(4), 332–344.

Rindova, V. P., Williamson, I. O., Petkova, A. P., & Sever, J. M. (2005). Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1033–1049.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2005). SmartPLS 2.0 M3 (beta). Hamburg. Retrieved from http://www.smartpls.de.

Roberts, P. W., & Dowling, G. R. (2002). Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1077–1093.

Robins, J. A. (2012). Partial-least squares. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 309–311.

Rose, C., & Thomsen, S. (2004). The impact of corporate reputation on performance: Some Danish evidence. European Management Journal, 22(2), 201–210.

Ruef, M., & Scott, W. R. (1988). A multidimensional model of organizational legitimacy: Hospital survival in changing institutional environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43, 877–904.

Rust, R., Lemon, K., & Zeithaml, V. A. (2004). Return on marketing: Using customer equity to focus marketing strategy. Journal of Marketing, 68, 109–124.

Sabate, J. M. D. L. F., & Puente, E. D. Q. (2003). Empirical analysis of the relationship between corporate reputation and financial performance: A survey of the literature. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(2), 161–177.

Schneeweiss, H. (2001). Consistency at large in models with latent variables. In K. Haagen, D. J. Bartholomew, & M. Deistler (Eds.), Statistical modeling and latent variables (pp. 299–320). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Schwartz, M. S., & Carroll, A. (2003). Social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(4), 503–530.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243.

Sharfman, M. (1996). The construct validity of the Kinder, Lydenberg & Domini social performance ratings data. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 287–296.

Shrum, W., & Wuthnow, R. (1988). Reputational status of organizations in technical systems. American Journal of Sociology, 93(4), 882–912.

Sijtsma, K. (2009). Reliability beyond theory and into practice. Psychometrika, 74(1), 169–173.

Smith, K. T., Smith, M., & Wang, K. (2011). Does brand management of corporate reputation translate into higher market value? Journal of Strategic Marketing, 18(3), 201–221.

Strike, V. M., Gao, J., & Bansal, P. (2006). Being good while being bad: Social responsibility and the international diversification of US firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 850–862.

Tenenhaus, M., Esposito Vinzi, V., Chatelin, Y. M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 48, 159–205.

Waddock, S. A., & Graves, S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4), 303–319.

Wang, H. L., & Qian, C. L. (2011). Corporate philanthropy and corporate financial performance: The roles of stakeholder response and political access. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1159–1181.

Wold, H. (1980). Model construction and evaluation when theoretical knowledge is scarce. In Evaluation of econometric model (pp. 47–74). Academic Press.

Wold, H. (1982). Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. Systems under indirect observation: Part II, 36–37.

Wood, D. J., & Jones, R. E. (1995). Stakeholder mismatching: A theoretical problem in empirical research on corporate social performance. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 3(3), 229–267.

Woodhouse, B., & Jackson, P. H. (1977). Lower bounds for the reliability of the total score on a test composed of non-homogeneous items: II: A search procedure to locate the greatest lower bound. Psychometrika, 42(4), 579–591.

Wright, P., & Ferris, S. P. (1997). Agency conflict and corporate strategy: The effect of divestment on corporate value. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 77–83.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(August), 197–206.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Barnett, Stephen Brammer, David Deephouse, Edwin Santbergen and Cees van Riel for their valuable inputs. We also thank the comments of the editor and three anonymous reviewers, which helped improve this study substantially.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix: A Robustness Check with a Full Set of KLD Indicators Using the Ordinary Least Squares Approach

In the PLS approach, we leave a number of KLD indicators out of the model, in order to improve the validity and reliability for the outer model. As a robustness check, we test our hypotheses with an ordinary least squares (OLS) approach, including all KLD indicators coded by the experts for a comparison. In the OLS approach, we use five CSP constructs, which are the unweighted aggregation of the underlying KLD indicators in each corresponding CSP dimension (see Table 3).

Hypotheses 1a and 1b predict that a higher financial and public reputation lead to a better financial performance. Our test of Hypothesis 1 confirmed the positive impacts. As Table A shows, reputations among financial and public stakeholders significantly influence financial performance (t value = 3.0619, p < 0.01 and t value = 3.5290, p < 0.01, respectively). Hypotheses 2a and 2b predict that reputations among financial and public stakeholders mediate the positive impacts of economic CSP on financial performance. Only the prediction in Hypothesis 2b is confirmed. We observe a significant positive effect of economic CSP on reputation among public stakeholders (t value = 4.0907, p < 0.01), and a significant effect of reputation among public stakeholders on financial performance, as described above. In addition, the bootstrap results in Table B show that the mediation effect is significant, since the 95 % confidence interval does not include 0 (0.024–0.1102). According to Zhao et al.(2010), with an insignificant direct effect of economic CSP on financial performance (t value = −0.233, p > 0.1), we can conclude that economic CSP only has an indirect positive effect on financial performance through reputation among public stakeholders.

Hypotheses 3a and 3b predict that reputations among financial and public stakeholders mediate the impact of (negative) legal CSP on financial performance. Both hypotheses are confirmed. We observe that zero is excluded from the 95 % confidence intervals for the indirect paths through both reputation among public stakeholders (−0.0585 to −0.0115) and reputation among financial stakeholders (−0.0387 to −0.0048).

Hypothesis 4a predicts that ethical CSP influences financial reputation positively. We observe that the impact of positive ethical CSP on financial performance, mediated through reputation among financial stakeholders, is comparable with the impact on reputation among public stakeholders, considering the 95 % confidence interval (from 0.0032 to 0.0235). The impact of negative ethical concern, on the other hand, is insignificant. These findings are supporting our hypotheses, and suggest that financial stakeholders support positive ethical CSP. Hypothesis 4b predicts that reputation among public stakeholders mediates the impact of ethical CSP on financial performance. Specifically, we expect a positive impact of positive ethical CSP on financial performance through reputation among public stakeholders, and a negative impact of negative ethical CSP. We observe that the bootstrap results are in support of the hypothesis. For positive ethical CSP, the lower and upper bounds of the 95 % confidence interval are 0.002 and 0.0281, whereas those for negative ethical CSP are −0.0509 and −0.002.

Hypothesis 5a predicts that philanthropic CSP has a negative impact on reputation among financial stakeholders. We find a significant negative effect of philanthropic CSP on financial reputation (t value = −2.2632, p < 0.05), and the upper and lower bonds of the 95 % confidence interval for the indirect effect are both negative (−0.031 to −0.0025). Therefore, Hypothesis 5a is confirmed. Hypothesis 5b predicts that reputation among public stakeholders mediates the positive impact of philanthropic CSP on financial performance. Observing positive upper and lower bonds of the 95 % confidence interval (0.0028 to 0.0385), we confirm our prediction in Hypothesis 5b. The contrasting impacts of philanthropic CSP on reputation among financial and public stakeholders suggest that while public stakeholders are in support of philanthropic CSP, financial stakeholders do not appreciate it. Instead, they may regard it as activities diverging firm resources from its core business.

Similar to the PLS analysis, we examine our data for potential violations of standard regression assumptions, such as heteroskedasticity, serial autocorrelation, and endogeneity. With respect to heteroskedasticity, the Koenker test has a p value of 0.059 (Koenker statistic = 20.471), suggesting that our model does not suffer from this issue. As for serial autocorrelation and endogeneity, the earlier mentioned arguments for our PLS analysis hold here too.

Results of the Robustness Checks

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Berens, G. The Impact of Four Types of Corporate Social Performance on Reputation and Financial Performance. J Bus Ethics 131, 337–359 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2280-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2280-y