Abstract

Recent studies have identified two important findings on infants’ capability of taking others’ perspectives and the difficulty of ignoring perspectives irrelevant to the acquired perspective. Unfortunately, there is insufficient consensus on the interpretation of these phenomena. Two important features of perspective-taking, embodiment and aging, should be considered to reach a more appropriate hypothesis. In this paper, the mechanism of perspective-taking can be redefined through the well-known process of self–other distinction, which is inherent to humans, without resorting to either the assumption of controversial systems or an excessive reduction to executive functions. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the implicit mentalizing observed in infancy comes from the loosening phenomenon and lasts lifelong and that the self-representation separated from one’s own body by the detachment function is sent to other perspectives for explicit perspective-taking. This hypothesis can not only explain both the robustness of perspective-taking in the older adults and the appearance of egocentric/altercentric bias in adults but also is consistent with the findings in brain science and neuropathology. Finally, some issues to be considered are presented to improve the validity of this hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Perspective-taking refers to the ability to recognize another person’s viewpoint and has two types: visual and social. Visual perspective-taking refers to the ability to visualize objects from the vantage point of an imaginary observer who has moved to some other point in space (Huttenlocher and Presson 1973). Social perspective-taking, however, refers to understanding others’ beliefs, feelings, or motivations and has been studied as mindreading, Theory of Mind (ToM), and mentalizing (Conway et al. 2017; Low et al. 2016). Both are essential for daily interactions with others and are pivotal for human development. Recently, a growing number of studies have suggested that even young children show altercentric responses and adults experience a deep influence from others’ perspectives. I will first present these findings briefly and show that there is insufficient consensus on the interpretation of these phenomena while presenting an overview of the major hypotheses and identifying their characteristics. Next, two points—embodiment and aging—are described, which have not been considered enough in the existing hypotheses. Thereafter, I will show that these hypotheses do not sufficiently answer the questions that arise from these points to present a possible alternative. Finally, the advantages and issues to be verified by this hypothesis are presented.

2 Two Groundbreaking Findings

The recent debate on perspective-taking has been sparked by two important findings: the understanding of perspectives in infancy and egocentric/altercentric bias. While children were thought to be incapable of mindreading before the age of 4, recent studies with less explicit measures have overturned this assumption. Some studies with implicit, non-verbal measures such as violation of expectation techniques, interactive techniques, and anticipatory-looking techniques have suggested that infants may use implicit perspective-taking. For example, the pioneering study of Onishi and Baillargeon (2005) discovered that 15-month-old infants demonstrated false-belief understanding, which was tested with the violation of expectation paradigm. Buttelmann et al. (2009) also showed a false-belief understanding of infancy through helping tasks. Recently, Király et al. (2018) provided clear evidence that eighteen-month-olds could track false beliefs based on episodic memories. Their results suggest that the ToM emerges much earlier than previously assumed. Additionally, Moll and Tomasello (2006) reported that 24-month-old children successfully handed an adult the occluded object in a case wherein one object was visible to all while another was visible only to the child, and Sodian et al. (2007) demonstrated that 14-month-old infants’ appropriate understanding of “seeing” using a looking-time paradigm. These reports indicate that even infants can take others’ perspectives.

Another important finding is the effects of distorted understanding on one’s own perspective and slower decision-making than usual, or conversely, facilitating the perceptual and memory processes (Mattan et al. 2015). These are called the “consistency effect” (Simpson and Todd 2017) or “altercentric bias” (Ferguson et al. 2018), which automatically occurs even in cases in which the others (avatars) are not directly relevant to the task. However, it has also been reported that when participants believed that another person could see the object, they were slower to judge their own perspective; such an altercentric bias did not occur when they believed that the other could not see the object (Furlanetto et al. 2016). This effect is not mandatorily triggered by the mere presence of others (Cole et al. 2017; Gardner et al. 2018), which indicates the awareness of another mind from the cues in the situation is essential for the biases to occur (Zwickel and Müller 2010). The opposite effect of this, well-known as “egocentric bias,” refers to a depression in the accuracy or speed of responses influenced by the self-perspective in the acquisition of another’s viewpoint; additionally, it stems from egocentrism that is characterized by the undifferentiation between the subject and the external world (Piaget and Inhelder 1948). For example, in a false-belief task, adults with knowledge of the object’s true location often overestimate the possibility that a person holding a false belief will search for that object in the correct location (Maehara and Saito 2011). Both altercentric and egocentric biases may emerge, therefore, from the difficulty of differentiating between the acquired perspective and irrelevant perspectives.

3 Recent Theoretical Conflicts

3.1 Two-systems Account

To explain the discrepancy between the findings that children younger than four years cannot pass explicit false-belief tasks, even though infants younger than two years pass implicit perspective-taking tasks, two kinds of ideas with somewhat different points have been proposed. One of them, the Two-Systems account, contains an early developing system that tracks simple mental states (an implicit system) and a later developing system based on conceptual belief (an explicit system). The former system works in a fast, automatic, and inflexible fashion, whereas the latter operates in a slower, controlled, and flexible fashion (Apperly and Butterfill 2009; Butterfill and Apperly 2013; Low et al. 2016). The implicit system is assumed to be evolutionarily and ontogenetically ancient. It is also shared by infants, children, and adults and is independent of cognitive resources such as working memories. In contrast, the explicit system develops later, is characteristic of older children, and makes substantial demands on executive functions. This means that the systems draw on separate conceptual resources. Because the same system cannot simultaneously be fast, slow, automatic, and effortful (Ferguson et al. 2015), these two distinct systems must be assumed. In fact, there was no link found between early mindreading measured at 14 and 18 months with the violation of expectation paradigm and explicit false-belief belief understanding at five years of age (Poulin-Dubois et al. 2020), which is indirect evidence of the existence of two qualitatively different systems. Furthermore, this accurate, rapid, and unconscious inference regarding their own and others’ perspectives makes it difficult for adults to completely ignore the unrelated perspective, thereby experiencing egocentric or altercentric interference, especially when two viewpoints are in conflict (Samson et al. 2010). Another kind of idea comes from nativists who argue that children already have perspective understanding when they pass an implicit false belief task, while they could fail an explicit one because of extra task demands (Baillargeon et al. 2010). They emphasize an implicit mechanism of mindreading; Scholl and Leslie (2001) expressed it as an “innate modular basis for the ToM” and Carruthers (2013) called it “basic mindreading capacities.” However, both Two-Systems proponents and nativists agree in believing that infants acquire implicit viewpoint acquisition functions early in their development.

3.2 Criticism from Submentalizing Accounts

There are objections to this claim that real perspective-taking exists in infants. On the early existence of Tom in infancy, for example, Dörrenberg et al. (2018) claimed that non-verbal methods of anticipatory-looking, looking times, pupil dilation in violation of expectation paradigms, and spontaneous communicative interaction—which have been frequently used to measure implicit ToM—were not reliable. Furthermore, Barone et al. (2019) performed a meta-analysis of the empirical evidence on spontaneous false belief in infants younger than two years and pointed out the dependence of the belief on the type of experimental paradigm and the suspicion of publication bias. Several other studies have questioned the replicability and robustness of spontaneous false beliefs in infancy (Cole et al. 2016; Crivello and Poulin-Dubois 2018; Edwards and Low 2019; Kulke et al. 2018a, b; Kulke et al. 2019a, b). Whether infants indeed possess what can be regarded as true implicit ToM is far from certain.

Even if we accept the implicit system, its identity is debatable (Kuhn et al. 2018). For example, Santiesteban et al. (2014) disagreed with the assumption of consistency effect—interpreted as the main evidence of implicit mentalizing—and showed that it was because of domain-general processes such as attentional orienting. More recently, Gardner et al. (2018) indicated that reflexive attention orienting may yield findings that explain the implicit perspective-taking process, and von Salm-Hoogstraeten et al. (2020) emphasized the referential coding for acting on the basis of others’ perspectives. These concepts that general information processing of the domain can provide fast and efficient substitute alternatives for implicit mentalizing are called “submentalizing” (Heyes 2014) or “minimalist” accounts (Ruffman 2014).

3.3 What’s Causing the Confusion?

After all, which accounts are appropriate remains controversial (Kulke et al. 2019a, b). This may be because these different positions may view the same phenomena in different ways or discuss different phenomena that they nevertheless believe to be the same (Cole and Millett 2019). In fact, they both explain the same phenomenon in different ways. Qureshi et al. (2020) view the implicit system, which is the crux of the Two-Systems accounts, as a complex construct that includes the inhibitory control function (Frick and Baumeler 2017), with which we can account for individual differences. Conversely, Baillargeon et al. (2018) concluded that the failures of replication of implicit understanding in infants often reported by submentalizing supporters can be explained by the procedural differences between studies. They warned that we should not short-circuit our conclusions because the possibility of mindreading in infancy, on which the Two-Systems accounts are based, remains. It is true that direct comparisons are made difficult by the confusions either derived from different standpoints with different theoretical perspectives or their experimental tasks in subtly different ways (O’Grady et al. 2020). In light of this, this clamor is similar to past controversies on “imagery” (Cole et al. 2020).

To overcome these problems, a unique idea has been proposed in recent years to reinterpret the implicit system and to show the inevitability of two different ways of perspective-taking. Southgate (2020) insisted that humans can take others’ perspectives without mature executive functions (implicit perspective-taking) only if their cognitive mechanism places attention on others with the simultaneous absence of a competing self-perspective; on the other hand, an intentional (explicit) perspective-taking system accompanying executive functions is required after the emergence of competition between self and others’ perspectives at age two (the altercentric hypothesis). Following this hypothesis, what makes it possible for infants to take other perspectives easily and spontaneously comes from the altercentric bias and not the early acquired perspective-taking system that is assumed in the Two-Systems accounts. The bias leads infants to understand others’ feelings or beliefs as self-evident only in unseparated situations of self and others, while the Two-Systems accounts explain that the once acquired implicit system can work in conjunction with the explicit system even in situations where self and others exist separately (e.g., in adults). Altercentricism in infants is not acquired by overcoming egocentrism (Piaget 1959) in their development; on the contrary, infants have altercentric tendencies from the onset, which gives them an advantage in understanding others. However, even this hypothesis has some weaknesses. After all, existing theories, including the altercentric hypothesis, do not adequately consider some of the important features of perspective-taking, which will be discussed below. We are now at a stage when we must stop and reconsider to determine if there is anything that has been overlooked. To determine a more appropriate hypothesis, I present two crucial points to be considered.

4 Two Crucial Questions

4.1 Embodiment

Perspective-taking is considered the psychological counterpart of the idiom “putting oneself in someone else’s shoes.“ In spatial perspective-taking, it is a mental simulation of the physical actions required to adjust to another person’s perspective (Erle and Topolinski 2017). Fischer and Demiris (2020) proved that this metaphor is psychologically real by using computational models to represent three types of response time differences in the angular disparity between a participant and avatar, body posture variations, and perspective-taking strategy differences. Such operation of embodied self-image is evident in children aged 4–12 (Hirai et al. 2020), students aged 18–24, and elderly people aged 63–76 (Watanabe 2011), and also in the inference of others’ beliefs in ToM (Xie et al. 2018). Additionally, the skill of balancing on one leg as an index for motor control is significantly related to children’s spatial performance (Frick and Möhring 2016) and the spatial perspective-taking of young and old people (Watanabe 2018). All these suggestions support the idea of embodied perspective-taking (Kessler and Thomson 2010).

Even though it is evident that perspective-taking is an embodied process, important things about its features have not yet been fully clarified. What part of the brain is responsible for the embodiment of perspective-taking, and how does it work? How does the embodied self in perspective-taking change throughout life? For the first question, Wang et al. (2016) used magnetoencephalography (MEG) and found that the mental operation of body schema results from a distributed network comprising body schema, somatosensory, and motor-related regions centered at the right Temporo-Parietal Junction (rTPJ). As reported in their research, deep participation of rTPJ in both social perspective-taking (ToM) (Kobayashi et al. 2007) and visual perspective-taking (Nijhof et al. 2018) has already been demonstrated. However, it is still not fully understood how embodied self-images are generated and controlled in the brain. To answer the second question, Watanabe (2016) showed that the effect of increased somatosensory stimulation on the performance of the perspective-taking task is the biggest in students, followed by young children and the older adults. However, there are no findings about why the embodied self changes its impact on perspective-taking during lifelong development. The role of embodiment in perspective-taking has not yet been sufficiently explored, even though it can be the key to innovations in future research. Therefore, it is important for an ideal hypothesis to adequately answer the question of why perspective-taking is characterized by embodiment.

4.2 Aging

Although many developmental studies have involved infants to young adults (Meinhardt-Injac et al. 2020; Symeonidou et al. 2016; Warnell and Redcay 2019), there are only a few reports on the changes in perspective-taking occurring from mid-adulthood to old age. One example of such aging research suggests that even older adults may show excellent performance in perspective-taking (Happé et al. 1998). De Beni et al. (2007) found that the older adults are inferior to students in mental rotation but superior in visual perspective-taking. Watanabe and Takamatsu (2014) used an original video game task to measure the implicit visual perspective-taking ability in eight age groups ranging from younger to older adults with a 10-year range. They also found that the oldest group performed similarly to the student group in taking perspectives, while the oldest group was inferior to the student group in spatial information processing. Additionally, it is known that compared to younger adults, the older adults experience difficulties in situations that require explicit perspective-taking. Grainger et al. (2018), for example, measured the eye movement patterns of older and younger adults in both explicit and implicit false-belief tasks and found that both age groups were not different in implicit false-belief processing, while older adults were inferior to younger ones in explicit ToM. In this way, it has been suggested that implicit false-belief understanding is maintained relatively well even in old age. For a more reasonable understanding of the features of lifelong development and aging in perspective-taking, we must correctly answer the question of how to explain the robustness of implicit perspective-taking in the older adults.

4.3 The Adequacy of the Theories

The Two-Systems accounts cannot fully account for the reason why an embodied self-image is deeply relevant to implicit and explicit perspective-taking. Ward et al. (2019) reported in implicit spatial perspective-taking that the well-known positive linear relationship between response times and angle of orientation was replicated, and that recognition becomes slower the more the participants must mentally rotate their perspectives to the canonical orientation of the item; however, this is the only possibility that the implicit system includes an embodied self-image. Similarly, the involvement of embodiment in the innate mindreading module from which the nativists claim that the implicit perspective-taking understanding emerges has not been fully examined the Two-Systems account is also unexpectedly weak for developmental interpretation, although it assumes systems with different emergence periods. There is insufficient explanation of the mechanism behind why the implicit system appears in infancy and is maintained thereafter. The explicit system is also assumed to be conventional perspective-taking that has been thoroughly studied, but the timing of its appearance and the effects of aging have not been fully examined to see whether they meet the predictions derived from the hypothesis. Additionally, evidence of the distinct systems has been gathered from two main approaches: research that finds its germ in infancy and research on egocentric/altercentric bias within adults; nonetheless, the attempts to apply the suggestions from infant research to adults and vice versa are insufficient, which leads to a danger of over-application of age-specific characteristics to other age groups without sufficient evidence. There has been little evidence derived from applying the same measurement method to compare two or more varying age groups, especially younger children and older adults, in the Two-Systems framework. In fact, the balance between the two functions in a visual perspective-taking task, operating perspectives and processing necessary spatial information, differs between infants and the older adults, even when they present the same number of correct answers (Watanabe and Takamatsu 2014), which means the possibility that the age groups use different strategies.

So, can the approach of submentalizing adequately explain developmental changes? The submentalizing accounts could be more adequate than the Two-Systems account if limited to adult ages; for example, it will be relatively easy to explain age-related decline, such as lower scores, in older adults than in younger people with declines in some executive functions. However, how can these hypotheses explain how perspective-taking, in practice, remains relatively well maintained while most cognitive functions generally decline with age. An example of such an explanation is that only the targeted functions are maintained at a high level, whereas the others decline with aging. For example, Long et al. (2018) examined the developmental relationship between perspective-taking and executive functions in two age groups—younger and older adults. They found that both age groups maintained their perspective-taking ability similarly; meanwhile, the difference between the two groups was that the older group’s scores in perspective-taking tasks were best captured by switching performance, whereas the younger group’s inhibitory performance predicted the scores. As shown in these results, perspective-taking ability may not be significantly compromised because all cognitive functions do not decline uniformly with aging (Hasan et al. 2011). However, in this case, it is noteworthy why the specific functions, which help to maintain perspective-taking, are fortunately selected to survive. Alternatively, we can assume that compensation between functions that is often observed in the older adults will maintain their performance, considering the finding that the executive functions that construct perspective-taking ability differ between age groups. Decreases in cognitive ability during old age in one hemisphere could be compensated for by other executive functions in the other hemisphere, assuming that the laterality in the prefrontal cortex, which is present at younger ages, decreases with age (Cabeza 2002). Nevertheless, it would be difficult to explain the superior understanding of others in the older adults with only compensation between executive functions because of an actual decline in many executive functions related to perspective-taking with aging (Treitz et al. 2007). In fact, there have been no successful reports of this description, including by nativists, who usually explain the development in terms of some changes in executive functions. Furthermore, this approach of submentalizing will be harder to apply to infants because it is difficult to capture their abilities as accurately and stably as adults’. Moreover, this account seems to pay little attention to the embodied features of perspective-taking.

In contrast, it seems that the altercentric hypothesis has more advantages than the Two-Systems or submentalizing accounts for describing the developmental data in mindreading. It considers innate altercentric tendencies as a source of implicit perspective-taking and explains the emergence of the explicit one as an outcome of the differentiation between self and others. In this sense, the altercentric hypothesis provides a good idea in which perspective-taking in children and infants can be explained in a different manner from the existing theories. Also, in terms of aging, its general assumption that a balance of memory traces between the self- and other-based representations determines which perspective to take might make it possible to better describe a sequential mechanism from infancy to old age. However, neither the details of the mechanism nor any demonstrable data have been presented. In this sense, the altercentric hypothesis is inadequate to describe the phenomenon of aging at this point.

Even if we accept the altercentric hypothesis as somewhat better than the Two-Systems or submentalizing accounts in describing the development of perspective-taking, there are still issues to be addressed. This is because this hypothesis does not sufficiently consider embodiment in perspective-taking, even though operating the embodied self-image is a central mechanism not only in visual perspective-taking but also in ToM. This defect may come from the whole reliance of the switching mechanism between self and other perspectives on the balance of memory traces as concepts of perception or cognition (de Guzman et al. 2016). It is necessary and natural to include the embodied self in the process of distinction between self and others, because the sense in which people feel that the entity performing the action is “me” is brought about not only by conceptual representations but also by sensory-motor information such as self-acceptance and visual feedback in the basal layer (Synofzik et al. 2008). The following section introduces a new idea to overcome these deficits.

5 Self–other Distinction for Perspective-Taking

5.1 Loosening Phenomenon

The self–other distinction plays an important role in understanding others’ mental states developmentally and neurocognitively (Steinbeis 2016). Although the nature of the developmental process of self–other distinction throughout infancy remains debated, there could be a consensus that the constant and repeated inputs of somatosensory information play an important role in the formation of a sense of self (Proulx et al. 2016) and that the true altercentricity is acquired in the first two years. Such subjective experiences through which people perceive their bodies foster feelings of self-ownership and self-agency (Gallagher 2000). A sense of self-ownership is the perception that the observed object belongs to one’s own body, and a sense of self-agency means perceiving the motion of the observed object as being caused by oneself. The first object that is perceived with a sense of self-ownership in infancy is one’s own body (Montirosso and McGlone 2020); this is because muscle tonus, which is involved in the posture maintenance mechanism and body temperature regulation mechanism, constantly provides passive resistance to muscle stretch, or interoception about the tension that the muscle makes (Palmer and Tsakiris 2018). The processing and awareness of bodily signals arising from visceral organs stabilizes the mental existence of oneself as distinct from others, and the sense of self-ownership is established resulting from that coherence of bodily self-awareness. Simultaneously, infants rely on multisensory processing of concurrent visual and tactile inputs to perceive the sense of self-agency in their physical and social surroundings (Lewkowicz and Bremner 2020). It is thought that parental mind-mindedness (Meins et al. 2002) and embodied simulation (Gallese 2009) also foster a sense of self-agency as a subject who works and is worked on. As a result, infants aged over 9 months become aware of the distinction between self and others; for example, they can be aware of others’ behavior, imitating their movements; and then they perceive their bodies as containers that are clearly separated from the outside and in which they exist as agents in the first year (Tomasello 1993).

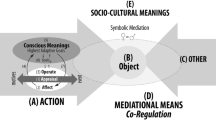

The bundled body senses through these processes, which generate self-ownership and self-agency, enhance the self–other distinction, and suppress the innate altercentric tendency. This ought to interfere with taking other perspectives with an altercentric bias in late infancy. However, the bundled body senses are loosened easily in some cases in young children. Hartmann (1991) proposed a personality dimension of thin vs. thick ego boundaries and considered that the nature of boundaries may vary depending on the situation and that thin boundaries may be associated with psychoticism or artistic creativity. Especially in the case of young children, the shackles of their physical selves often seem to loosen easily, as evidenced by their thin ego boundaries. It can be considered that this loosening phenomenon of the self–other distinction allows the resurgence of altercentric bias and gives the infant access to the perceptions and beliefs of others again (Fig.1). Following this assumption, among the previous reports on infants’ competency in mentalizing, some can be interpreted as examples of the emergence of altercentric bias before self–other distinction at eight months (Choi et al. 2018; Kampis et al. 2015; Kovács et al. 2010; Luo and Johnson 2009; Southgate and Vernetti 2014), while the other with over nine months can be because of the reappearance of altercentric tendency because of the loosened physical self in specific task situations (Luo and Baillargeon 2007; Onishi and Baillargeon 2005; Surian and Geraci 2012; Thoermer et al. 2012). In fact, one of the former studies (Kovács et al. 2010) reported that 7-month-old infants automatically pay attention to both others’ beliefs and their own beliefs similarly, whereas one of the latter ones (Luo and Baillargeon 2007) found that 12.5-month-old infants can suppress their own more complete representation to use the agent’s representations for interpreting others’ actions. Thus, the loosening phenomenon makes it possible to implicitly take others’ perspectives, even after the establishment of a self–other distinction. However, this phenomenon is not the same as the implicit system of perspective-taking in the Two-Systems account because evolutionarily it is not acquired for the purpose of perspective-taking; conversely, implicit perspective-taking may be a byproduct of this function. Indeed, an overreliance on fast, automatic, biased mentalizing and, as a result, the conflation of the mental states of self and others is often observed in people with borderline personality disorder who are characterized by thin ego boundaries (Luyten et al. 2021).

Here, we must pay attention to the fact that behaviors such as perspective-taking by the altercentric bias before self–other distinction are not true perspective-taking. Perspective-taking needs an imaginary observer and the other to be observed, which is achieved after self–other distinction. Joint actions such as affective entrainment, which can be seen in the undifferentiated state of self and others in younger infants, could also not be considered as a perspective-taking behavior, because it is not accompanied by a sense of self-agency. Although human infants can engage in rich social interaction shortly after birth because of their altercentric nature, the state of coexistence with others during this period should not be considered true perspective-taking.

It is assumed that the loosening phenomenon appears in our embodied self throughout life, even after the self–others distinction in late infancy. Therefore, this phenomenon can not only describe the mechanism of implicit perspective-taking but also the egocentric/altercentric biases in lifelong development, including old age. The egocentric bias, which means that the self-perspective interferes with the other ones to be taken, is caused by the difficulty of abandoning the self-consciousness that originated from the somatosensory information once the self and others have become distinct. This indicates that somatosensory information is mixed more or less into their altercentric judgments even in adulthood. In fact, sensorimotor interference (Riecke et al. 2007), which means that characteristics such as the limits of body motion or direction of movement appear in the reaction times and correct response rates in body representational operations, has also been observed in adults. On the contrary, altercentric bias, which means that we are influenced by information about other perspectives even though our own perspective is required to be taken, arises because it is difficult to completely separate ourselves from others and close ourselves off from the outside world. The rubber hand illusion (Botvinick and Cohen 1998), which is the feeling of ownership of a rubber hand displaced from an occluded real hand with synchronously stroking both hands, is a good example of this. The physical self constantly perceives information from the outside for a lifelong time. Therefore, the altercentric bias has been often observed in young children and participants adult participants.

5.2 Detachment Function

There is also something inadequate about explicit perspective-taking in the altercentric hypothesis. It is not suitable to contrastively consider the self and other representations as the beginning of explicit perspective-taking because other representations do not constantly mean the perspective of a specific other. Rather, it is suitable to define another representation as one other than the self-body schema. In fact, healthy people will experience difficulty in simultaneously imagining both self-representation and their self-body schema, while those with hallucinatory symptoms unintentionally have an experience of viewing their own body from another self, which indicates confusion between self-representation and the real body (Blanke and Arzy 2005). In this sense, explicit perspective-taking could be defined as a process of separating self-representation from self-body schema. More attention should be paid to the resistance in trying to “detach” the self-representation from the self-body schema, which occurs when some characteristics of one’s own body are detached from inherent experiences and behaviors to externalize them as self-representations (Wallon 1934), than on the conflicts between self- and other-based representations. This detachment function means dividing the self-body schema from the external world in a state where self and others are distinct under the control of the antecedent loosening phenomenon. But once the self and other distinction is loosened, the innate altercentric tendency should reappear as altercentric bias, even in adults. Thus, this hypothesis of loosening and detachment in the process of objectifying the self-body could describe as a byproduct of such functions both the lifelong appearance of spontaneous or intentional perspective-taking and the mechanism of frequent shifting between egocentric and altercentric perspectives.

It should be noted that this developmental sequence of loosening phenomena and detachment function does not correspond to the well-known developmental stages—Level 1 or virtual perspective-taking of what someone else sees and Level 2, or identifying how someone else sees (Flavell et al. 1981). Level 1 refers to the process of movement of one’s own perspective to other positions, and Level 2 includes information processing in addition to the process of Level 1 to derive others’ beliefs or views. Loosening and detachment are included in both Levels 1 and 2 to a varying degree. My hypothesis focuses on the division process of perspectives, which is common to these two levels and is most crucial in perspective-taking activities; on the contrary, Two-Systems and submentalizing accounts intend to describe all the processes, including actual reactions in perspective-taking activities. Even considering the insufficiency of my hypothesis in theoretical inclusiveness, it is worthy of consideration as follows.

5.3 Advantages and Issues

In this paper, it is argued that the mechanism of perspective-taking can be redefined from that inherent to humans through the well-known process of self–other distinction without resorting to either the assumption of novel systems or an excessive reduction of executive functions. Therefore, it was hypothesized that implicit perspective-taking by altercentric tendency in infancy lasts throughout life because of the loosening phenomenon, even after self–other distinction, and that the self-representation is separated from the self-body image with the detachment function to be used for explicitly taking perspectives. This new hypothesis compensates for the features of embodiment and aging in perspective-taking that are lacking in the altercentric hypothesis. It can also explain a series of self–other distinction processes in both the decline of explicit perspective-taking performance and the robustness of implicit perspective-taking in the older adults, as well as the appearance of egocentric/altercentric bias in adults. However, evidence from empirical data is not yet sufficient. In particular, compared with perspective-taking in children, fewer studies have examined perspective-taking in aging. Nevertheless, our hypothesis may be more useful than other explanations in that it provides a consistent explanation for the findings already available and allows us to recognize perspective-taking development in lifespan.

Although we have been looking for a perspective-taking module for a long time, this may have been a false assumption from the beginning. Humans have acquired the ability to objectify themselves through evolution, which may make it possible to take other perspectives as a second-order effect. In fact, it has been reported that some kinds of apes exhibit mirror self-recognition responses very similar to human infants (Inoue-Nakamura 2001), and they also seem to be capable of implicitly taking perspectives (Buttelmann et al. 2017; Krupenye et al. 2016). However, the differences between humans and apes are also important. For example, Tomasello (2018) introduced the concept of shared intentionality to explain why only older children pass some kinds of false-belief tasks, whereas both infants and apes pass others. This shared intentionality of coordinating self and other perspectives for understanding other people as agents may facilitate the detachment process to explicitly take others’ perspectives. In short, it seems that the loosening phenomenon works for understanding in early life of the other intentions, with such joint actions being common to both humans and apes; on the other hand, the detachment function has a core role in intentional mindreading as humans’ specific activities. The progress in comparative psychology may lead us to verify these anticipations in the near future.

Additionally, the central role of the embodied self in this hypothesis is consistent with the fact that rTPJ is deeply involved in perspective-taking. For example, Blanke and Arzy (2005) and Blanke and Mohr (2005) conducted a meta-analysis of previous studies that reported on patients who exhibited hallucinatory symptoms such as autoscopy and out-of-body experiences, which are abnormal phenomena in which the world is perceived from a position outside the physical body; they found that rTPJ is generally involved in these kinds of experiences. Blanke et al. (2005); Arzy et al. (2006a, b) similarly pointed out the involvement of the rTPJ by examining brain activity in autoscopy patients. It is also known that stimulation of the angular gyrus, a part of rTPJ, can produce an out-of-body experience (Arzy et al. 2006a, b). Considering the intersectional role of the rTPJ in tactile, auditory, and visual processing, as well as the suggestion that out-of-body experiences are somatosensory disruptions (Braithwaite and Dent 2011), it can be inferred that some processing of the embodied self-image takes place in the rTPJ. It is expected that compatibility with brain science will certify this hypothesis (Luyten et al. 2021).

So, can it be stated that this hypothesis has as much or more explanatory power than other theories? The Two-Systems account, in which the features of the systems are defined according to the existing experimental results, and the submentalizing accounts, in which some general functions can be freely selected to explain the experimental results, have goodness in terms of their adequateness in describing the findings from research. However, my hypothesis can also describe them as reasonably as the existing theories without resorting to either the assumption of controversial systems or an excessive reduction in executive functions. For example, it could provide a satisfactory explanation for the difference between implicit and explicit perspective-taking. Grosse Wiesmann et al. (2020) found that children aged three years were worse in the explicit false-belief tasks than those aged four years above, whereas there was not a significant difference between these groups in the implicit false-belief tasks. Additionally, they reported that explicit false-belief tasks correlate with linguistic abilities, whereas implicit false-belief tasks do not. These facts could be described as follows: the loosening phenomenon, which an individual is already equipped with at three years and is driven without verbalizing, made all the children pass the implicit false-belief tasks, whereas only the four-year-old group passed the explicit false-belief tasks, in which the detachment function is needed to induce a self-representation for intentional perspective-taking. Additionally, relatively poor performance on an explicit false-belief task compared to an implicit one in the older adults (Grainger et al. 2018) could be explained by assuming that the deterioration of operating self-representations because of the decline of cognitive functions and motor organs in normal aging disturbs the detachment function, whereas the physical self, which concerns the loosening phenomenon, is more robust against aging. Whether such explanations are overwhelmingly more effective than those from the Two-Systems account or submentalizing accounts remains to be seen. More research is needed in the fields of self-psychology, developmental psychology, and brain science to elucidate the features of the loosening phenomenon and detachment function and show the validity of the hypothesis with careful attention to not adding excess assumptions to try to reconcile the results.

First, the existence of the loosening phenomenon and detachment function must be demonstrated with concrete evidence. In particular, the loosening phenomenon is a new concept that has not been examined before, and simultaneously, it seems to be difficult to define operationally; therefore, difficulties in demonstrating it are expected. The reaction time independent of the distance between self and other perspectives, which Watanabe (2016) and Watanabe and Takamatsu (2014) successfully separated, could be a good clue for the loosening phenomenon according to their presumption that it is an essential process of their implicit perspective-taking tasks. Alternatively, a surprising phenomenon that sensory-motor stimulation to human bodies enhanced their performance in an implicit perspective-taking task (Watanabe 2016) could indicate that the increase in attention to one’s own body helps trigger the loosening phenomenon. Moreover, if the assumption of the loosening phenomenon is correct, some qualitative changes in the performance of implicit perspective-taking are expected around age nine months, when the embodied self is thought to be established. Additionally, the verification of this prediction, the existence of the loosening phenomenon and detachment function must be clarified.

Second, the recently reported effects of empathy and emotions on perspective-taking should be incorporated into the hypotheses. For example, Todd and Simpson (2016) reported that anxiety disrupts spontaneous visual perspective-taking. Bukowski and Samson (2016) also found that guilt made participants more altercentric while anger made them more egocentric in Level 1 visual perspective-taking tasks. It should be noted that these effects were found in implicit perspective-taking, in which the loosening phenomenon would be strongly involved. Judging from the fact that the development of emotional empathy is rooted in early infancy and supports the ability to differentiate between self and others in daily empathic experiences (Tousignant et al. 2017), and that various emotional experiences are encoded to map within rTPJ in the brain (Lettieri et al. 2019), it could be assumed that the emotional changes loosened or strengthened the bonds of the physical self, depending on the circumstances. Thus, although it is also possible to reasonably interpret some findings on emotions under the assumption of a loosening phenomenon, more efforts should be made to further improve the consistency of this hypothesis based on future findings.

Finally, many important research questions on developmental changes and individual differences can be derived from the characteristics of the loosening phenomenon and detachment function. For example, why is the loosening phenomenon, which supports implicit perspective-taking, maintained relatively well even in later life, despite the general decline of physical functions in aging? Does the detachment function follow the development of general cognition, such as executive functions, because of the indispensable features of manipulating representations, or is it strongly influenced after all by one’s own body because of the constraints imposed by the embodied self? Is it safe to assume that those with autism spectrum disorder or phenomena such as autoscopy or out-of-body experiences have trouble with the healthy development of a sense of self? Although there are many issues to be resolved, the concepts of perspective-taking based on the self–other distinction are expected to lead to major developments in developmental psychology and psychopathology.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Apperly, Ian A., and Stephen A. Butterfill. 2009. Do humans have two systems to track beliefs and belief-like states? Psychological Review 116: 953–970. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016923.

Arzy, Shahar, Margitta Seeck, Stephanie Ortigue, Laurent Spinelli, and Olaf Blanke. 2006a. Induction of an illusory shadow person. Nature 443: 287. https://doi.org/10.1038/443287a.

Arzy, Shahar, Gregor Thut, Christine Mohr, M. Christoph, Michel, and Olaf Blanke. 2006b. Neural basis of embodiment: Distinct contributions of temporoparietal junction and extrastriate body area. Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 26: 8074–8081. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0745-06.2006b.

Baillargeon, Renée, David Buttelmann, and Victoria Southgate. 2018. Invited Commentary: Interpreting failed replications of early false-belief findings: Methodological and theoretical considerations. Cognitive Development 46: 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2018.06.001.

Baillargeon, Renée, Rose M. Scott, and Zijing He. 2010. False-belief understanding in infants. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 14: 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.006.

Barone, Pamela, Guido Corradi, and Antoni Gomila. 2019. Infants’ performance in spontaneous-response false belief tasks: A review and meta-analysis. Infant Behavior and Development 57: 101350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2019.101350.

Blanke, Olaf, and Shahar Arzy. 2005. The out-of-body experience: Disturbed self-processing at the temporo-parietal junction. Neuroscientist: A Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology Neurology and Psychiatry 11: 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858404270885.

Blanke, Olaf, and Christine Mohr. 2005. Out-of-body experience, heautoscopy, and autoscopic hallucination of neurological origin implications for neurocognitive mechanisms of corporeal awareness and self-consciousness. Brain Research Brain Research Reviews 50: 184–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.05.008.

Blanke, Olaf, Christine Mohr, Christoph M. Michel, Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Peter Brugger, Margitta Seeck, Theodor Landis, and Gregor Thut. 2005. Linking out-of-body experience and self processing to mental own-body imagery at the temporoparietal junction. Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 25: 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2612-04.2005.

Botvinick, Matthew, and Jonathan Cohen. 1998. Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature 391: 756. https://doi.org/10.1038/35784.

Braithwaite, Jason J. and Kevin Dent. 2011. New perspectives on perspective-taking mechanisms and the out-of-body experience. Cortex; a Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior 47: 628–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2010.11.008.

Bukowski, Henryk, and Dana Samson. 2016. Can emotions influence level-1 visual perspective taking? Cognitive Neuroscience 7: 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17588928.2015.1043879.

Buttelmann, David, Frances Buttelmann, Malinda Carpenter, Josep Call, and Michael Tomasello. 2017. Great apes distinguish true from false beliefs in an interactive helping task. PLOS ONE 12: e0173793. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173793.

Buttelmann, David, and Malinda Carpenter, and Michael Tomasello. 2009. Eighteen-month-old infants show false belief understanding in an active helping paradigm. Cognition 112: 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2009.05.006.

Butterfill, Stephen A, and I. A. N. A. Apperly. 2013. How to construct a minimal theory of mind. Mind and Language 28: 606–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12036.

Cabeza, Roberto. 2002. Hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults: The HAROLD model. Psychology and Aging 17: 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.17.1.85.

Carruthers, Peter. 2013. Mindreading in infancy. Mind and Language 28: 141–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12014.

Choi, You-Jung, Yi Mou, and Yuyan Luo. 2018. How do 3-month-old infants attribute preferences to a human agent? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 172: 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2018.03.004.

Cole, Geoff G., A. Mark, D. C. Atkinson, Antonia, D’Souza, and Daniel T. Smith. 2017. Spontaneous Perspective taking in Humans? Vision 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision1020017.

Cole, Geoff G., A. Mark, T. D. Atkinson, An, Le, and Daniel T. Smith. 2016. Do humans spontaneously take the perspective of others? Acta psychologica 164: 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2016.01.007.

Cole, Geoff G., and Abbie C. Millett. 2019. The closing of the theory of mind: A critique of perspective-taking. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 26: 1787–1802. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01657-y.

Cole, Geoff G., C. Abbie, Steven Millett, Samuel, and J. Madeline, and Eacott. 2020. Perspective-taking: In search of a theory. Vision 4: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision4020030.

Conway, Jane R., Danna Lee, Mobin Ojaghi, and Caroline Catmur, and Geoffrey Bird. 2017. Submentalizing or mentalizing in a Level 1 perspective-taking task: A cloak and goggles test. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance 43: 454–465. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000319.

Crivello, Cristina, and D. Poulin-Dubois. 2018. Infants’ false belief understanding: A non-replication of the helping task. Cognitive Development 46: 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2017.10.003.

De Beni, Rossana, Francesca, Pazzaglia, and Simona Gardini. 2007. The generation and maintenance of visual mental images: Evidence from image type and aging. Brain and Cognition 63: 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2006.09.004.

de Guzman, Marie, Geoffrey Bird, Michael J. Banissy, and Caroline Catmur. 2016. Self–other control processes in social cognition: From imitation to empathy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences 371: 20150079. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0079.

Dörrenberg, Sebastian, H., Rakoczy, and U. Liszkowski. 2018. How (not) to measure infant theory of mind: Testing the replicability and validity of four non-verbal measures. Cognitive Development 46: 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2018.01.001.

Edwards, Katheryn, and Jason Low. 2019. Level 2 perspective-taking distinguishes automatic and non-automatic belief-tracking. Cognition 193: 104017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.104017.

Erle, Thorsten M., and Sascha Topolinski. 2017. The grounded nature of psychological perspective-taking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 112: 683–695. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000081.

Ferguson, Heather J., A. Ian, Jumana Apperly, Markus Ahmad, Bindemann, and James Cane. 2015. Task constraints distinguish perspective inferences from perspective use during discourse interpretation in a false belief task. Cognition 139: 50–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.02.010.

Ferguson, Heather J., E. A. Victoria, Brunsdon, and E. F. Elisabeth, and Bradford. 2018. Age of avatar modulates the altercentric bias in a visual perspective-taking task: ERP and behavioral evidence. Cognitive Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience 18: 1298–1319. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-018-0641-1.

Fischer, Tobias, and Y. Demiris. 2020. Computational Modelling of Embodied Visual Perspective-Taking. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems 12: 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCDS.2019.2949861.

Flavell, John H., A. Barbara, Karen Croft Everett, and R. Eleanor, and Flavell. 1981. Young children’s knowledge about visual perception: Further evidence for the Level l – Level 2 distinction. Developmental Psychology 17: 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.17.1.99, https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.17.1.99.

Frick, Andrea, and Wenke, and Möhring. 2016. A matter of balance: Motor control is related to children’s spatial and proportional reasoning skills. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 2049. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02049.

Frick, Andrea, and Denise Baumeler. 2017. The relation between spatial perspective taking and inhibitory control in 6-year-old children. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung 81: 730–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-016-0785-y.

Furlanetto, Tiziano, Cristina Becchio, Dana Samson, and Ian A. Apperly. 2016. Altercentric interference in level 1 visual perspective taking reflects the ascription of mental states, not submentalizing. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance 42: 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000138.

Gallagher, Shaun. 2000. Philosophical conceptions of the self: Implications for cognitive science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4: 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01417-5.

Gallese, Vittorio. 2009. Mirror neurons, embodied simulation, and the neural basis of social identification. Psychoanalytic Dialogues 19: 519–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/10481880903231910.

Gardner, Mark R., Zainabb Hull, Donna Taylor, and Caroline J. Edmonds. 2018. ‘Spontaneous’ visual perspective-taking mediated by attention orienting that is voluntary and not reflexive. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 71: 1020–1029. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2017.1307868.

Grainger, Sarah A., D. Julie, Claire K. Henry, Marita S. Naughtin, Comino, and Paul E. Dux. 2018. Implicit false belief tracking is preserved in late adulthood. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 71: 1980–1987. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021817734690.

Grosse Wiesmann Charlotte, Angela D. Friederici, Tania Singer, and Nikolaus Steinbeis. 2020. Two systems for thinking about others’ thoughts in the developing brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117: 6928–6935. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916725117.

Happé, Francesca G. E., Ellen Winner, and Hiram Brownell. 1998. The getting of wisdom: Theory of mind in old age. Developmental Psychology 34: 358–362. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.358.

Hartmann, Ernest. 1991. Boundaries in the mind: A new psychology of personality. Basic Books.

Hasan, Khader M., S. Indika, Humaira Walimuni, Richard E. Abid, Linda Frye, Jerry S. Ewing-Cobbs, Wolinsky, and Ponnada A. Narayana. 2011. Multimodal quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of thalamic development and aging across the human lifespan: Implications to neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 31: 16826–16832. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4184-11.2011.

Heyes, Cecilia. 2014. Submentalizing: I am not really reading your mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 9: 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613518076.

Hirai, Masahiro, Yukako Muramatsu, and Miho Nakamura. 2020. Role of the embodied cognition process in perspective-taking ability during childhood. Child Development 91: 214–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13172.

Huttenlocher, Janellen, and Clark C. Presson. 1973. Mental rotation and the perspective problem. Cognitive Psychology 4: 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(73)90015-7.

Inoue-Nakamura, Noriko. 2001. Mirror self-recognition in primates: An ontogenetic and a phylogenetic approach. In Primate origins of human cognition and behavior, ed. Tetsuro. Matsuzawa, 297–312. Springer.

Kampis, Dora, Eugenio Parise, Gergely Csibra, and Ágnes, Melinda, and Kovács. 2015. Neural signatures for sustaining object representations attributed to others in preverbal human infants. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 282(1819): 20151683–20151683. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.1683.

Kessler, Klaus, and Lindsey Anne Thomson. 2010. The embodied nature of spatial perspective taking: Embodied transformation versus sensorimotor interference. Cognition 114: 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2009.08.015.

Király, Ildikó, Katalin Oláh, Gergely Csibra, and Kovács Ágnes Melinda. 2018. Retrospective attribution of false beliefs in 3-year-old children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115: 11477–11482. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1803505115.

Kobayashi, Chiyoko, and Gary H. Glover, and Elise Temple. 2007. Children’s and adults’ neural bases of verbal and nonverbal “theory of mind”. Neuropsychologia 45: 1522–1532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.11.017.

Kovács, Ágnes, Erno Melinda, Téglás, and Endress Ansgar Denis. 2010. The social sense: Susceptibility to others’ beliefs in human infants and adults. Science 330: 1830–1834. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1190792.

Krupenye, Christopher, Fumihiro Kano, Satoshi Hirata, Josep Call, and Michael Tomasello. 2016. Great apes anticipate that other individuals will act according to false beliefs. Science 354: 110–114. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8110. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8110.

Kuhn, Gustav, Ieva Vacaityte, Antonia D. C. D’Souza, Abbie C. Millett, and Geoff G. Cole. 2018. Mental states modulate gaze following, but not automatically. Cognition 180: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.05.020.

Kulke, Louisa, Mirjam Reiß, Horst Krist, and Hannes Rakoczy. 2018a. How robust are anticipatory looking measures of theory of mind? Replication attempts across the life span. Cognitive Development 46: 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2017.09.001.

Kulke, Louisa, Josefin Johannsen, and Hannes Rakoczy. 2019a. Why can some implicit theory of mind tasks be replicated and others cannot? A test of mentalizing versus submentalizing accounts. PLOS ONE 14: e0213772. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213772.

Kulke, Louisa, Britta von Duhn, Dana Schneider, and Hannes Rakoczy. 2018b. Is implicit theory of mind a real and robust phenomenon? Results from a systematic replication study. Psychological Science 29: 888–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617747090.

Kulke, Louisa, Marieke Wübker, and Hannes Rakoczy. 2019b. Is implicit theory of mind real but hard to detect? Testing adults with different stimulus materials. Royal Society Open Science 6: 190068. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190068.

Lettieri, Giada, Giacomo Handjaras, Emiliano Ricciardi, Andrea Leo, Paolo Papale, Monica Betta, Pietro Pietrini, and Luca Cecchetti. 2019. Emotionotopy in the human right temporo-parietal cortex. Nature Communications 10: 5568. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13599-z.

Lewkowicz, David J., and Andrew J. Bremner. 2020. The development of multisensory processes for perceiving the environment and the self. In Multisensory perception: From laboratory to clinic, eds. Krishnankutty Sathian, and Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, 89–112. Academic Press.

Long, Madeleine R., S. William, Hannah Horton, Rohde, and Antonella Sorace. 2018. Individual differences in switching and inhibition predict perspective-taking across the lifespan. Cognition 170: 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.09.004.

Low, Jason, Ian A. Apperly, and Stephen A. Butterfill, and Hannes Rakoczy. 2016. Cognitive architecture of belief reasoning in children and adults: A primer on the two-systems account. Child Development Perspectives 10: 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12183.

Luo, Yuyan, and Renée, and Baillargeon. 2007. Do 12.5-month-old infants consider what objects others can see when interpreting their actions? Cognition 105: 489–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.10.007.

Luo, Yuyan, and Susan C. Johnson. 2009. Recognizing the role of perception in action at 6 months. Developmental Science 12: 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00741.x.

Luyten, Patrick, Celine De Meulemeester, and Peter Fonagy. 2021. The self–other distinction in psychopathology: Recent developments from a mentalizing perspective. In The neural basis of mentalizing, eds. Michael Gilead, and N. Kevin, and Ochsner. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51890-5_34.

Maehara, Yukio, and Satoru Saito. 2011. I see into your mind too well: Working memory adjusts the probability judgment of others’ mental states. Acta Psychologica 138: 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.09.009.

Mattan, Bradley, Kimberly A. Quinn, Ian A. Apperly, Jie Sui, and Pia Rotshtein. 2015. Is it always me first? Effects of self-tagging on third-person perspective-taking. Journal of Experimental Psychology Learning Memory and Cognition 41: 1100–1117. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000078.

Meinhardt-Injac, Bozana, Moritz M., Daum, and G. ünter Meinhardt. 2020. Theory of mind development from adolescence to adulthood: Testing the two-component model. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 38: 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12320.

Meins, Elizabeth, Charles Fernyhough, Rachel Wainwright, Mani Das Gupta, Emma Fradley, and Michelle Tuckey. 2002. Maternal mind-mindedness and attachment security as predictors of theory of mind understanding. Child Development 73: 1715–1726. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00501.

Moll, Henrike, and Michael Tomasello. 2006. Level 1 perspective-taking at 24 months of age. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 24: 603–613. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X55370.

Montirosso, Rosario, and Francis McGlone. 2020. The body comes first. Embodied reparation and the co-creation of infant bodily-self. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 113: 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.03.003.

Nijhof, Annabel D., Lara Bardi, Marcel Brass, and Jan R. Wiersema. 2018. Brain activity for spontaneous and explicit mentalizing in adults with autism spectrum disorder: An fMRI study. NeuroImage Clinical 18: 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.02.016.

O’Grady, Cathleen, Thom Scott-Phillips, Suilin Lavelle, and Kenny Smith. 2020. Perspective-taking is spontaneous but not automatic. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 73: 1605–1628. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021820942479.

Onishi, Kristine H., and Renée, and Baillargeon. 2005. Do 15-month-old infants understand false beliefs? Science 308: 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1107621. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1107621.

Palmer, Clare E., and Manos Tsakiris. 2018. Going at the heart of social cognition: Is there a role for interoception in self-other distinction? Current Opinion in Psychology 24: 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.008.

Piaget, Jean. 1959. La formation du symbole chez l’enfant: Imitation, jeu et rêve, image et représentation (2ème éd). Delachaux et Niestlé.

Piaget, Jean, and Bärbel, and Inhelder. 1948. La représentation de l’espace chez l’enfant. Presses Universitaires de France.

Poulin-Dubois, Diane, Naomi Azar, Brandon Elkaim, and Kimberly Burnside. 2020. Testing the stability of theory of mind: A longitudinal approach. PLOS ONE 15: e0241721. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241721.

Proulx, Michael J., S. Orlin, T. Todorov, Amanda, Taylor Aiken, and Alexandra A. de Sousa. 2016. Where am I? Who am I? The Relation Between Spatial Cognition, Social Cognition and Individual Differences in the Built Environment. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 64. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00064.

Qureshi, Adam W., L. Rebecca, Dana Monk, Samson, and Ian A. Apperly. 2020. Does interference between self and other perspectives in theory of mind tasks reflect a common underlying process? Evidence from individual differences in theory of mind and inhibitory control. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 27: 178–190. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01656-z.

Riecke, Bernhard E., W. Douglas, Cunningham, and Heinrich H. Bülthoff. 2007. Spatial updating in virtual reality: The sufficiency of visual information. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung 71: 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-006-0085-z.

Ruffman, Ted. 2014. To belief or not belief: Children’s theory of mind. Developmental Review 34: 265–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.04.001.

Samson, Dana, Ian A. Apperly, Jason J. Braithwaite, Benjamin J. Andrews, and Sarah E. Bodley Scott. 2010. Seeing it their way: Evidence for rapid and involuntary computation of what other people see. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance 36: 1255–1266. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018729.

Santiesteban, Idalmis, Caroline Catmur, Senan Coughlan Hopkins, Geoffrey Bird, and Cecilia M. Heyes. 2014. Avatars and arrows: Implicit mentalizing or domain-general processing? Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance 40: 929–937. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035175.

Scholl, Brian J., and A. M. Leslie. 2001. Minds, modules, and meta-analysis. Child Development 72: 696–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00308.

Simpson, Austin J., and Andrew R. Todd. 2017. Intergroup visual perspective-taking: Shared group membership impairs self-perspective inhibition but may facilitate perspective calculation. Cognition 166: 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.06.003.

Sodian, Beate, and Claudia Thoermer, and Ulrike Metz. 2007. Now I see it but you don’t: 14-month-olds can represent another person’s visual perspective. Developmental Science 10: 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-7687.2007.00580.X.

Southgate, Victoria. 2020. Are infants altercentric? The other and the self in early social cognition. Psychological Review 127: 505–523. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000182.

Southgate, Victoria, and Angelina Vernetti. 2014. Belief-based action prediction in preverbal infants. Cognition 130: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2013.08.008.

Steinbeis, Nikolaus. 2016. The role of self-other distinction in understanding others’ mental and emotional states: Neurocognitive mechanisms in children and adults. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences 371: 20150074. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0074.

Surian, Luca, and Alessandra Geraci. 2012. Where will the triangle look for it? Attributing false beliefs to a geometric shape at 17 months. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 30: 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02046.x.

Symeonidou, Irene, Iroise Dumontheil, Wing-Yee Chow, and Richard Breheny. 2016. Development of online use of theory of mind during adolescence: An eye-tracking study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 149: 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2015.11.007.

Synofzik, Matthis, and Gottfried Vosgerau, and Albert Newen. 2008. Beyond the comparator model: A multifactorial two-step account of agency. Consciousness and Cognition 17: 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2007.03.010.

Thoermer, Claudia, Beate Sodian, Maria Vuori, Hannah Perst, and Susanne Kristen. 2012. Continuity from an implicit to an explicit understanding of false belief from 74 infancy to preschool age. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 30: 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02067.x.

Todd, Andrew R., and Austin J. Simpson. 2016. Anxiety impairs spontaneous perspective calculation: Evidence from a level-1 visual perspective-taking task. Cognition 156: 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2016.08.004.

Tomasello, Michael. 1993. The interpersonal origins of self concept. In The perceived self: Ecological and interpersonal sources of self-knowledge, ed. Ulric Neisser. Cambridge University Press.

Tomasello, Michael. 2018. How children come to understand false beliefs: A shared intentionality account. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115: 8491–8498. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804761115.

Tousignant, B., Fanny éatrice, Eugène, and Philip L. Jackson. 2017. A developmental perspective on the neural bases of human empathy. Infant Behavior and Development 48: 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.11.006.

Treitz, Friederike H., Katrin Heyder, and Irene Daum. 2007. Differential course of executive control changes during normal aging. Neuropsychology Development and Cognition Section B Aging Neuropsychology and Cognition 14: 370–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825580600678442.

von Salm-Hoogstraeten, Sophia, Katharina Bolzius, and Jochen, and Müsseler. 2020. Seeing the world through the eyes of an avatar? Comparing perspective taking and referential coding. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance 46: 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000711.

Wallon, Henri. 1934. Les origines du caractère chez l’enfant: Les préludes du sentiment de personnalité. Presses Universitaires de France.

Wang, Hongfang, Eleanor Callaghan, Gerard Gooding-Williams, Craig McAllister, and Klaus Kessler. 2016. Rhythm makes the world go round: An MEG-TMS study on the role of right TPJ theta oscillations in embodied perspective taking. Cortex; a Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior 75: 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2015.11.011.

Ward, Eleanor, Giorgio Ganis, and Patric Bach. 2019. Spontaneous vicarious perception of the content of another’s visual perspective. Current Biology: CB 29: 874–880.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.046.

Warnell, Katherine Rice, and Elizabeth Redcay. 2019. Minimal coherence among varied theory of mind measures in childhood and adulthood. Cognition 191: 103997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.06.009.

Watanabe, Masayuki. 2018. Does the controllability of the body schema predict equilibrium in elderly people? Characteristics of relationships from a lifelong development perspective. Journal of Aging Science 6: 1000191. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-8847.1000191.

Watanabe, Masayuki. 2011. Distinctive features of spatial perspective-taking in the elderly. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 72: 225–241. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.72.3.d.

Watanabe, Masayuki. 2016. Developmental changes in the embodied self of spatial perspective taking. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 34: 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12126.

Watanabe, Masayuki, and Midori Takamatsu. 2014. Spatial perspective taking is robust in later life. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 78: 277–297. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.78.3.d.

Xie, Jiushu, Him Cheung, Manqiong Shen, and Ruiming Wang. 2018. Mental rotation in false belief understanding. Cognitive Science 42: 1179–1206. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12594.

Zwickel, Jan, and Hermann J. Müller. 2010. Observing fearful faces leads to visuo-spatial perspective taking. Cognition 117: 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2010.07.004.

Funding

This work was supported by The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Number 19H01754.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, M. Are Mentalizing Systems Necessary? An Alternative Through Self–other Distinction. Rev.Phil.Psych. 15, 29–49 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-022-00656-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-022-00656-8