Abstract

Recent empirical research demonstrates that cross-holding engenders significant anti-competitive effect even though it confers no decisive influence on the target firm. This research has obtained wide attention, which leads to both calls for and actual changes in antitrust policy. However, the effects of cross-holding on competition are not well established. This paper examines the collusive effect of cross-holding with asymmetry in cost functions across firms in an infinitely repeated Cournot duopoly game. The two firms have a different share of capital that affects marginal costs. We find that cross-holding facilitates collusion when a small firm (i.e., a firm with a small capital capacity) increases its passive ownership in a big firm (i.e., a firm with a large capital capacity), and the size of initial ownership is relatively small. Unexpectedly, collusion becomes more difficult to be sustained when a big firm increases ownership in a small firm, or when a small firm increases ownership in a big firm but the initial ownership is relatively large. Our result that cross-holding may either facilitate or hinder collusion, under certain circumstances, generates important implications for antitrust policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Recent prominent examples include the following cases. In November 2006, the BSkyB acquired 17.9% of ITV. The UK Competition Commission concluded that the acquisition of 17.9% of shares in ITV would lessen competition considerably and ordered to reduce it to a level below 7.5%. In 2009, the Commission scrutinized the case IPIC/MAN Ferrostaal where MAN Ferrostaal held a minority stake in Eurotecnica, and requested MAN Ferrostaal to divest its shareholdings. In 2013, the Competition Commission investigated Ryanair’s acquisition in Aer Lingus and required Ryanair to sell its 29.8% stake down to 5%. More examples can be found in Fadiga (2019).

Cross-holdings raise two main antitrust concerns: concerns about unilateral effect in static games and concerns about coordinated effect in repeated games. See also in Gilo et al. (2006), and Annex to the Commission Staff Working Document, Towards more effective EU merger control, SWD (2013) 239 final. In this paper, we focus on the latter and examine the effect of cross-holding on the collusive stability of firms.

Empirically, Alley (1997) study the effect of cross-holdings on collusion with the data of automobile industry, and find that Japanese automobile manufacturers behave collusively in the domestic market. Parker and Röller (1997) use panel data collected in the United States during the period of 1984–1988, and conclude that cross-ownership and multimarket contact are two important factors that lead to non-competitive prices. Interestingly, Hu et al. (2014) conduct empirical studies with the data of the Chinese automobile industry to examine whether horizontal collusion in price exists, and find no clear evidence supports within-group collusion.

Depart from Malueg (1992), de Haas and Paha (2016) introduce asymmetric cross-holdings and a competition authority into a repeated Cournot duopoly. The authors conclude that cross-holdings would destabilize collusion under a greater variety of situations in the presence of an antitrust authority that pursues an effective anti-cartel policy.

European Commission, “Support Study for Impact Assessment Concerning the Review of Merger Regulation Regarding Minority Shareholdings.”

It is important to note that there are critical differences between cross-holdings and mergers. First, cross-holdings only involve partial non-controlling acquisitions and allow independent decisions by these engaged firms. But mergers refer to full controlling acquisitions which reduce the number of firms in the market. This is also the main argument why merger control rules cannot be extended to cover cross-holdings in most countries. Second, cross-holdings only alter firms’ incentives through financial interests but do not change the production possibility of firms. That is, there are no capital transfer between firms. However, mergers bring the individual capital of the merging firms under a single larger firm, and thus result in endogenous efficiency gains (Vasconcelos 2005).

Since our focus in this paper is to examine the collusive effect of cross-holding, we propose a very simple model with only one of the two firms owning a share of the rival. The assumption of unilateral cross-holding is widely used in the literature such as Farrell and Shapiro (1990), Gilo et al. (2013), Ghosh and Morita (2017), Liu et al. (2018), and Hsu et al. (2019), etc. As we see later, the acquiring firm can be either the one with a larger capacity or that with a smaller capacity.

In a repeated Bertrand oligopoly model with n identical firms, Gilo et al. (2006) use a similar approach to express the profit of each firm under collusion. Under partial cross ownership, if all firms charge the monopoly price, then each owns \(\Pi ^M/n\) in equilibrium. Thus, cross-holdings do not change the allocated share of monopoly profit for each firm. Similarly, Gong (2018) study the collusive effect of an asymmetric partial cross ownership un Cournot competition, and assume a uniform/proportional output distribution in the collusion phase, i.e., each firm produces \(Q^M/n\) under asymmetric cross-holdings. More discussions about the output/profit sharing rule can be found in Footnote 9 and Conclusion.

Such a sharing rule is also used in Vasconcelos (2005). Furthermore, Vasconcelos (2005, pp. 43–44) provides a significant amount of anecdotal evidence which suggests that output shares were allocated between colluding firms on the basis of production capacity. Examples include oil exploitation industry in the Unites States, cement industry in Norway, heavy industries in Japan, and a global lysine industry, etc.

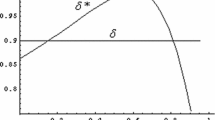

The explicit expressions for both \({\underline{k}}(\theta )\) and \({\overline{k}}(\theta )\) are complicated, and thus are not included in the text. With the help of numerical computing software, Mathematica, we plot \({\underline{k}}(\theta )\) and \({\overline{k}}(\theta )\) for any given \(\theta\) in Fig. 1. The analysis could become more complicated and difficult with an alternative output/profit sharing rule other than the proportional-subgame-perfect equilibria approach used in this paper.

It is usually believed that symmetry is a factor conducive to collusion, since the asymmetry between firms creates incentives to deviate both in the collusive phase and the punishment phase. The European Commission notes in its Guidelines that “firms may find it easier to reach a common understanding on the terms of coordination if they are relatively symmetric.” Similarly, the US Horizontal Merger Guidelines state that “reaching terms of coordination may be facilitated by product or firm homogeneity.”

Ganslandt et al. (2012) studied mergers (i.e., \(\theta =1\)) and collusion in a differentiated product Bertrand model and found that firms do collude only when asymmetries are moderate.

In Malueg (1992) which considers symmetric bilateral shareholdings in a Cournot duopoly, the common critical discount factor decreases with ownership acquisition under linear demand. Gilo et al. (2006) instead analyze the collusive effect of cross-holding in a Bertrand oligopoly model with n firms. The authors show that the critical discount factor for each firm i weakly decreases with ownership acquisition.

A working paper, Gong (2018), also finds out that increasing ownership in the target may hinder collusion. The analysis is conducted in the framework of an identical Cournot oligopoly. In this paper, increasing ownership always facilitates collusion for a linear or concave demand, which is exactly the same as that obtained by Malueg (1992). However, when demand is convex, the effects of increasing ownership are ambiguous.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out this direction.

References

Alley, W. A. (1997). Partial ownership arrangements and collusion in the automobile industry. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 45, 191–205.

Barcena-Ruiz, J. C., & Campo, M. L. (2012). Partial cross-ownership and strategic environmental policy. Resource and Energy Economics, 34, 198–210.

Barcena-Ruiz, J. C., & Olaizola, N. (2007). Cost-saving production technologies and partial ownership. Economics Bulletin, 15(6), 1–8.

Brito, D., Ribeiro, R., & Vasconcelos, H. (2019). Can partial horizontal ownership lessen competition more than a monopoly? Economics Letters, 176, 90–95.

Clayton, M. J., & Jorgensen, B. N. (2005). Optimal cross holding with externalities and strategic interactions. The Journal of Business, 78(4), 1505–1522.

de Haas, S., & Paha, J. (2016). Partial cross ownership and collusion. Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics 32-2016, Marburg.

Dietzenbacher, E., Smid, B., & Volkerink, B. (2000). Horizontal intergration in the Dutch financial sector. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 18, 1223–1242.

European Commission. (2014). White paper: Towards more effective EU merger control. Brussels, 9.7.2014. COM (2014) 449 final.

Fadiga, R. (2019). Horizontal shareholding within the European Competition Law Framework: Discussion of the proposed solutions. European Competition Law Review, 40(6), 157–65.

Fanti, L. (2016). Interlocking cross-ownership in a unionised duopoly: When social welfare benefits from ‘more collusion. Journal of Economics, 119(1), 47–63.

Farrell, J., & Shapiro, C. (1990). Asset ownership and market structure in oligopoly. The Rand Journal of Economics, 21(2), 275–292.

Ganslandt, G., Persson, L., & Vasconcelos, H. (2012). Endogenous mergers and collusion in asymmetric market structures. Economica, 79, 766–791.

Ghosh, A., & Morita, H. (2017). Knowledge transfer and partial equity ownership. The Rand Journal of Economics, 48(4), 1044–1067.

Gilo, D., Spiegel, Y., & Temurshoev, U. (2013). Partial cross ownership and tacit collusion under cost asymmetries. Working Paper, Tel-Aviv University.

Gilo, D., Moshe, Y., & Spiegel, Y. (2006). Partial cross ownership and tacit collusion. The Rand Journal of Economics, 37, 81–99.

Gong, Z. (2018). Tacit collusion of partial cross ownership under Cournot model. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3306203.

Hsu, J., Liu, L., Wang, X. H., & Zeng, C. H. (2019). Ad valorem versus per-unit royalty licensing in a Cournot duopoly model. The Manchester School, 87(6), 890–901.

Hu, W. M., Xiao, J., & Zhou, X. (2014). Collusion or competition? Interfirm relationships in the Chinese Auto Industry. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 62(1), 1–40.

Jain, R., & Pal, R. (2012). Mixed duopoly, cross-ownership and partial privatization. Journal of Economics, 107(1), 45–70.

Li, S. X., Ma, H. K., & Zeng, C. H. (2015). Passive cross holding as a strategic entry deterrence. Economics Letters, 134, 37–40.

Liu, L., Lin, J., & Qin, C. (2018). Cross-holdings with asymmetric information and technologies. Economics Letters, 166, 83–85.

López, Á. L., & Vives, X. (2019). Overlapping ownership, R&D spillovers, and antitrust policy. Journal of Political Economy, 127(5), 2394–2437.

Ma, H. K., Qin, C., & Zeng, C. H. (2019). Incentive and welfare implications of cross-holdings in oligopoly. Working paper.

Malueg, D. A. (1992). Collusive behavior and partial ownership of rivals. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 10, 27–34.

Mukhopadhyay, S., Kabiraj, T., & Mukherjee, A. (1999). Technology transfer in duopoly the role of cost asymmetry. International Review of Economics & Finance, 8(4), 363–374.

Nain, A., & Wang, Y. (2018). The product market impact of minority stake acquisitions. Management Science, 64(2), 825–844.

Parker, P. M., & Röller, L. H. (1997). Collusive conduct in duopolies: Multimarket contact and cross-ownership in the mobile telephone industry. The Rand Journal of Economics, 28(2), 304–322.

Reynolds, R., & Snapp, B. (1986). The competitive effects of partial equity interests and joint ventures. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 4, 141–153.

Shuai, J., Xia, M. Y., & Zeng, C. H. (2020). Upstream market structure and downstream cross holding. Working paper.

Trivieri, F. (2007). Does cross-ownership affect competition?: Evidence from the Italian Banking Industry. Journal of International Financial Markets Institutions and Money, 17(1), 79–101.

Vasconcelos, H. (2005). Tacit collusion, cost asymmetries, and mergers. The Rand Journal of Economics, 36(1), 39–62.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions that have helped to greatly improve the paper. We also thank Chengzhong Qin, X. Henry Wang, and Leonard F. S. Wang for their insightful comments. Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71773030), the Humanity and Social Science Planning Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 20YJA790001), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law (Grant No. 2722019JCT039), and Shanghai Pujiang Program (Grant No. 17PJC024) are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of Proposition 1

In the following, we show that \({\underline{k}}(\theta )<{\overline{k}}(\theta )\) holds for all \(\theta <0.5\). Denote by \(T(\theta , k)={(\pi _{1}^{M}/\pi _{1}^{N})}/{(\pi _{2}^{M}/\pi _{2}^{N})}\). Simple calculations yield that

We then obtain that \(\partial ^{2} T(\theta , k) /\partial k \partial \theta <1\), which implies that \({\underline{k}}(\theta )<{\overline{k}}(\theta )\) since both \({\underline{k}}(\theta )\) and \({\overline{k}} (\theta )\) decrease in \(\theta\).

1.2 Proof of Lemma 1

Based on (13) and (14), it can be shown that \(0< \widehat{\delta _1 }<1\) and \(0< \widehat{\delta _2 }<1\) when \({\underline{k}}(\theta )<k<{\overline{k}}(\theta )\). Furthermore, straightforward calculations lead to

where

\(Y=54-3 \theta (23+\theta (-7+(-3+\theta ) \theta ))-(-3+\theta )^2 (-1+\theta ) k \left( -3 (1+\theta )+(-1+\theta ) k\right)\).

Similarly, we obtain that \({\partial \widehat{\delta _2}}/{\partial \theta }>0\), where

1.3 Proof of Lemma 2

The justification of existence of \({\tilde{k}}(\theta )\) in \(\left( {\underline{k}}(\theta ),{\overline{k}}(\theta )\right)\) which solves \(\widehat{\delta _{1}}=\widehat{\delta _{2}}\) is based on the following facts: (i) \(0<\widehat{\delta _{1}}<1\) and \(0<\widehat{\delta _{2}}<1\) when \({\underline{k}} (\theta )<k<{\overline{k}}(\theta )\); (ii) \({\partial \widehat{\delta _{1}}}/{ \partial \theta }<0\) and \({\partial \widehat{\delta _{2}}}/{\partial \theta } >0\) by Lemma 1; and (iii) \(\widehat{\delta _{1}}=\widehat{\delta _{2}}\) when \(\theta =0\) and \({k=0.5}\), or equivalently, \({\tilde{k}}(0)=0.5\). Furthermore, simple calculations yield that \({\partial \widehat{\delta _{1}}}/{ \partial k}<0\) and \({\partial \widehat{\delta _{2}}}/{\partial k}>0\) based on (12) and (13). Consequently, \(\widehat{\delta _{1}}<\widehat{\delta _{2}}\) when \(k>{\tilde{k}}(\theta )\), while \(\widehat{\delta _{1}}>\widehat{\delta _{2}}\) otherwise. Implied by the two sets of partial derivatives: \({\partial \widehat{\delta _{i}}}/{\partial \theta }\) and \({\partial \widehat{\delta _{i}}}/{\partial k}\) for \(i=1,2\), we can obtain that \({\tilde{k}}(\theta )\) decreases in \(\theta\).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Zeng, C. Collusive stability of cross-holding with cost asymmetry. Theory Decis 91, 549–566 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-021-09822-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-021-09822-3