“I have always believed that the Good Samaritan went across the road to the wounded man just because he wanted to.” Wilfred Grenfell

Abstract

Although the literature on organizational justice enactment is becoming richer, our understanding of the role of the deontic justice motive remains limited. In this article, we review and discuss theoretical approaches to and evidence of the deontic justice motive and deontic justice enactment. While the prevalent understanding of deontic justice enactment focuses on compliance, we argue that this conceptualization is insufficient to explain behaviors that go beyond the call of duty. We thus consider two further forms of deontic behavior: humanistic and supererogatory behavior. Drawing on the concepts of situation strength and person strength, we further argue that the reduced variance in behavior across morally challenging situations makes deontic justice enactment visible. We thus observe deontic justice enactment when an actor’s deontic justice motive collides with strong situational cues or constraints that guide the actor to behave differently. We formulate propositions and develop a theoretical model that links the deontic justice motive to moral maturation and deontic justice enactment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The literature on organizational justice has documented that moral virtues provide an important explanation of why people care about justice, referred to as the “deontic justice motive” (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Folger, 1998, 2001). However, two important aspects, defined as “managerial actions that act in accordance with the [justice rule] standards” (Scott et al., 2009, p. 758), have not been considered in the literature on justice enactment. First, although morality represents one of the key building blocks of justice, the deontic motive of organizational members who perform and enact justice (henceforth referred to as “managers”) has received limited attention compared to other justice motives (Diehl et al., 2021; Graso et al., 2019; Qin et al., 2018). Second, researchers have illustrated that managers are not always able to act upon their motives, leading to a growing stream of studies investigating why justice concerns are sometimes compromised (Sherf et al., 2019; Zwank et al., 2022). Although the reasons are often traced to strong situational constraints in organizations (Jennings et al., 2015; Treviño et al., 2006), recent research has pointed to internal struggles over moral issues relating to justice enactment (Camps et al., 2022; Zwank et al., 2022). Thus, the question of why some individuals break through the blinders imposed on them by organizational pressures, resist moral compromises, and still enact deontic justice—even if doing so means hazarding negative consequences for themselves—remains underresearched.

Interestingly, a plethora of studies examining unethical decision-making have concluded that misconduct often arises from “bad apples,” “dark” personality traits, or “bad barrels” (Kish-Gephart et al., 2010). Research adopting the “bad apple” perspective has shed light on individuals who lack or ignore human, fair, or moral concerns. Research has investigated the “dark” side of organizational life, even using the umbrella concept “corporate psychopaths,” a term referring to individuals, or even organizations, who “ruthlessly manipulate others, without conscience, to further their own aims and objectives” (Boddy, 2011, p. 256). This line of research has borne considerable fruit and yielded interesting results for a number of distinct but related concepts ranging from the “dark triad” of personality (Glenn & Sellbom, 2015; Paulhus & Williams, 2002), abusive or bad leadership (Babiak, 1995; Boddy, 2011; Kellerman, 2004; Tepper, 2007), or bad actors (Zhong & Robinson, 2021) to specific aversive behaviors and psychosocial outcomes, including aggression and violence (Dinić & Wertag, 2018; Pailing et al., 2014), workplace deviance (Giacalone & Greenberg, 1997), bullying (Parzefall & Salin, 2010), immorality (Seabright & Schminke, 2002), moral disengagement (Bandura, 1999), or counterproductive work behaviors (Forsyth et al., 2012; Spain et al., 2014).

Although some branches of the broader management literature have started to examine the good in organizations and managers using lenses such as responsible leadership (Doh & Stumpf, 2005; Pless et al., 2012) or conscious capitalism (e.g., Fyke & Buzzanell, 2013), the predominant focus on the dysfunctional has led to a lack of understanding and investigation of the functional aspects—the “bright” (instead of dark) side of managers. To understand, predict, and influence managerial justice enactment and to promote justice in workplaces, we need to define and conceptualize the term “deontic justice” as precisely as possible, differentiate it from other organizational behaviors, and locate it in a nomological net of antecedents/predictors (both dispositional and situational) and consequences. Hence, in this paper, we begin illuminating the personological and contextual interaction that influences deontic justice enactment, thereby advancing the understanding of the behavior of corporate samaritans as an antonym for corporate psychopaths (Boddy, 2011).

To date, the literature has predominantly considered deontic justice as requirement-based rule-following, as a duty (Cropanzano et al., 2003, p. 1020), or as a justice imperative (Lerner, 2015) built on so-called compliance behaviors (Dasborough et al., 2020). The earliest conceptualizations of deontic justice, however, offered a more faceted perspective and drew on supererogation as a category of behaviors that are praiseworthy yet at the same time not necessarily obligatory (e.g., Heyd, 2019). Even the ancient Greeks, Plato and Aristotle, regarded justice as a virtue tied to an internal state of the person rather than to (adherence to) social norms or to good consequences (Aristotle, 2009; Plato, 1992; Slote, 2010)—an important nuance that has largely been lost in the contemporary literature. Consequently, we start our examination by unpacking and broadening the term deontic justice enactment. Specifically, we argue that deontic justice enactment extends to two additional distinct behavioral categories that go beyond compliance, namely, humanistic and supererogatory behaviors (Dasborough et al., 2020; Ilies et al., 2013). Justice enactment is thus not only about fulfilling minimum duties but also about striving for ideals and inner rightness. By building on and extending the scientific discourse on the “morality of aspiration” vs. the “morality of obligation” (Van der Burg, 2009), we focus on prescriptive (acts of benevolence) rather than proscriptive (inhibition of harm) behaviors (Dasborough et al., 2020; Janoff-Bulman et al., 2009), which we argue are part of deontic justice enactment.

Stating that the (strength of the) deontic justice motive predicts deontic justice enactment would be a truism, a conceptual tautology, and lead to trivial, non-falsifiable claims (such as “Justice enactment should be called deontic only if it is rooted in a deontic justice motive”). This is not our intention in this paper. Rather, we aim to clarify what a deontic justice motive is and when and under what circumstances it leads to deontic justice enactment. To do so, we first introduce two further concepts, both adopted from the rich literature on person-situation interactionism (e.g., Fleeson, 2004; Funder, 2006; Kihlstrom, 2013; in the organizational behavior literature, see Treviño, 1986), namely, situation strength and person strength. In short, we propose that justice enactment is deontic to the extent that managers act in accordance with their level of moral maturation even though situational specifications incentivize them to behave differently. In other words, we argue that deontic justice enactment—in its richest form—is seen as the behavior of strong (i.e., morally mature) persons in strong situations that enforce morally questionable behavior.

Individuals’ thinking about right and wrong does not emerge in a vacuum; rather, it is strongly affected by context (e.g., Bamberger, 2008; Cappelli & Sherer, 1991; Mowday & Sutton, 1993). A valuable concept for our theorizing was introduced by Mischel (1973), who extended the simple assertion that context is important by proposing the concept of situation strength. Situation strength refers to the degree to which situational constraints that guide people’s behaviors are present (Caspi & Moffitt, 1993; Judge & Zapata, 2015; Schmitt et al., 2013). Specifically, “strong” situations trigger uniform behavior and diminish interindividual variability in behavior, thus reducing the predictive validity of personality traits. In contrast, a situation is “weak” when individual behavior is unconstrained by norms, conventions, or rituals to the point that interindividual variability is more strongly predicted by stable individual traits and characteristics. In fact, a multitude of studies have emphasized that the organizational context can be considered mostly “strong” (Mowday & Sutton, 1993). Rules, structures, expectations of others, social relationships, the nature of tasks, physical characteristics of the job, obvious norms, or rigid rules thereby provide clear guidance regarding the expected behavior (Johns, 2006; Judge & Zapata, 2015; Meyer et al., 2010a, 2010b; Schneider & Hough, 1995). Person strength is analogous to situation strength: when a person is “strong,” their behavior across a number of situations is more consistent than that of a “weak” person. The notion of person strength (and its conceptual relation to situation strength) was discussed in detail by Schmitt et al., (2013; see also Blum et al., 2018; Blum & Schmitt, 2017). In brief, we posit that it is exactly the reduced variance in behavior across morally challenging and intense situations that allows us to identify justice enactment as “deontic.”

Toward Understanding Managers’ Motives for Justice Enactment

An extensive body of studies has proven the strong impact of (in)justice on various attitudinal and behavioral outcomes in both favorable and unfavorable directions (Colquitt et al., 2001, 2005; Folger & Skarlicki, 2001; Koopman et al., 2019). Most of this research has investigated the consequences of fairness while treating organizational justice as an independent variable (Brockner et al., 2015). Research on the potential antecedents of fairness that focuses specifically on managers’ role as justice actors—in other words, on justice as a dependent variable—has only recently started to emerge (Diehl et al., 2021; Graso et al., 2019).

In 2009, Scott and colleagues presented a conceptual framework that focuses specifically on actors (i.e., managers) and their motives for enacting justice. Drawing on Simon (1964), the authors defined motive simply as a reason or cause for behaving in a particular way. According to the framework, both “cold” cognitive and “hot” affective motives drive managers’ adherence to justice rules. With “cold” cognitive motives, managers adhere to justice rules due to their desire to induce compliance in their subordinates (corresponding to the instrumental motive in the literature on employee motivation for caring about justice), to create and maintain desired identities (corresponding to the relational motivation among employees), and simply to establish fairness (corresponding to the deontic justice motivation). “Hot” affective motives, in turn, capture a positive and negative affective state that influences managers’ justice rule adherence, whereby positive (negative) affect tends to motivate individuals to engage in several actions that are prosocial (antisocial) in nature, even if exceptions exist (see Scott et al., 2014).

Taking stock of the small body of literature on justice enactment, Graso et al. (2019) observed a threefold structure that, similar to cognitive motives, corresponds to the established motives of justice recipients for caring about justice: instrumental motives that involve an understanding of justice as a means to an end (Homans, 1961), relational motives based on a consideration of justice as a means to manage relationships (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Rai & Fiske, 2011), and deontic motives based on an understanding of justice as an end in itself (Folger, 1998, 2001). In other words, individuals care about and enact justice not only because of its instrumental or relational implications but also because of a universal imperative that all individuals should be treated fairly (Folger & Skarlicki, 2001). A similar assertion was proposed by Qin et al. (2018), who, building on functional theories of attitudes (Katz, 1960), distinguished motives for justice according to whether they are purported to benefit oneself (i.e., instrumental) or intended to express core values and beliefs (i.e., value-expressive). Beyond this, people can also be interested in fair treatment to reduce perceived uncertainty (Diehl et al., 2018; Lind & Van den Bos, 2002), for example, in the context of organizational change (Diehl et al., 2013; Elovainio et al., 2005).

While the literature has thus identified several reasons that drive managers’ intentions to enact justice, most attention has thus far been given to the instrumental justice motive, reflecting a similar emphasis in the early work on employee justice motives (Graso et al., 2019). Other researchers have proposed the orthogonality of justice motives and considered them to operate concurrently, thereby influencing managers’ justice behavior in an interactive fashion (Qin et al., 2018). At the same time, Graso et al (2019) and Diehl et al. (2021) emphasized that our understanding of the role of the deontic motive in justice enactment remains underdeveloped compared to our knowledge of the other motives.

Justice Enactment as Deonance

The literature on moral judgment differentiates two broad categories of morality: the axiological (also called the evaluative) and the deontic. While most ethical theories attest to these two categories of morality, their emphases differ. Axiological, or evaluative, concepts (from the Latin valor or the Greek axios, both meaning “worthy”) are used to express states such as approval or disapproval, and deontic concepts (from the Greek deon, meaning that which is binding) are used to express what to do and not to do (Tappolet, 2013). At the intersection of the axiological and the deontic lies supererogation, a category of actions that are praiseworthy yet, strictly speaking, not obligatory (Heyd, 2019).

Supererogation defines a sphere of action that is meritorious but not ethically required. Acts that are supererogatory go “beyond the call of duty” (Heyd, 2019) and are typically other-regarding, such as altruistic or exceptionally beneficent deeds (Beauchamp, 2019). Specifically, traditional approaches to ethics have divided human action into three categories: acts that agents have an obligation to perform (duties), acts that they have an obligation to omit (wrongdoing), and acts that are morally neutral and deserve neither praise nor blame (indifferent; see Tencati et al., 2020). Modern ethics (e.g., Urmson, 1958) has expanded this three-part classification and made room for supererogation, that is, “acts which are morally praiseworthy but not obligatory to perform and whose omission is not blameworthy” (Mellema, 1991, p. 149). Urmson (1958, p. 215) regarded the traditional three-pronged classification as inadequate, with “many kinds of action that involve going beyond duty proper, saintly and heroic actions being conspicuous examples.” These kinds of actions stem from an inner imperative to live up to the highest ideals of behavior that the agent can imagine, regardless of whether these ideals are strictly obligatory. Such behaviors are captured by the notion of “genuine altruism” in social psychology research (Batson & Shaw, 1991).

Controversies arise regarding how supererogation can be ethically praiseworthy but not ethically obligatory (Tencati et al., 2020). Acts of supererogation are optional, but it seems that good ethics requires “that one ought not take a complacent or indifferent attitude toward performing them” (Mellema, 1991, p. 153). Interestingly, modern ethics argues for a “good-ought tie-up” (Heyd, 2019), proposing that if there are valid moral reasons for taking an action, then these reasons are conclusive, and we ought to act on them. The agents consider themselves morally “bound” to perform the act, although the action is not a duty. In other words, good is never optional (e.g., Feldman, 1986; Pybus, 1982). These are actions that are praiseworthy, and although omitting them is not blameworthy, it is plainly wrong (Cohen, 2013; Tencati et al., 2020). In addition, as such acts make the actor worthy of moral praise and are clearly not wrong, it is inadequate to call them permissible—yet they do not fall under the three traditional categories. Hence, another moral classification is needed that includes them (Pybus, 1982). It thus stands to reason that supererogation relates to the deontic sphere and may also grow out of moral virtues.

In the organizational justice literature, the deontic motive points to moral virtues that guide the treatment of others (Cropanzano et al., 2001, 2017; Folger, 2001). Deontic justice, viewed as a value for its own sake (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Graso et al., 2019) rather than as something enacted for personal or organizational benefits, then occurs as and results from a moral duty to uphold ethical principles (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Folger, 2001; Folger et al., 2005). While the term “deontic” is rooted in the Greek term “deon” (duty), the few previous studies focusing on deontic justice have referred to it in relation to requirement-based, moral rule-following reasons for action (Cropanzano et al., 2003). In this context, a rule is understood in terms of universal ethical principles rather than situational if–then contingencies (Rupp & Bell, 2010; Wood, 1999). Deontic principles as a type of moral judgment are not directly concerned with tangible benefits, such as reputation or control of outcomes; rather, they are independent of the potential consequences of one’s own behavior or of factors serving economic self-interest or group-based identity (Cropanzano et al., 2003). However, in contrast to altruism, which prioritizes others, the deontic justice motive includes both the self and others: it is about “neither me nor you only (…) sometimes you first, but sometimes me first (it depends on what’s fair)” (Folger, 2001, p. 10).

Research has documented that the deontic motive provides a critical account of why employees care about justice (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Folger, 1998, 2001). The deontic motive has also been argued to be the main driver of justice concerns for third parties who have observed others experiencing injustice (e.g., Cropanzano et al., 2003; Lin & Loi, 2021; Turillo et al., 2002; Umphress et al., 2013). In line with this notion, Folger (2001) showed that witnessing injustice creates a desire for offenders to be held accountable for their moral wrongdoing. Hence, justice and ethical behavior are naturally co-occurring phenomena independent of possible system controls or individual self-interest (Montada, 1996, 2002; Rupp & Bell, 2010).

While the examination of recipients’ and observers’ perspectives has borne considerable fruit, only a handful of studies have considered the deontic perspective of managers (for a review, see Graso et al., 2019). Previous research, however, has indicated that justice enactment can also be “a matter of moral imperative” (Qin et al., 2018; Zwank et al., 2022) and attributed managers’ interest in fair treatment to the character of the actor, such as caring for others or moral obligation (Brebels et al., 2011; Patient & Skarlicki, 2010). In their actor-focused model of justice enactment, Scott et al. (2009) recognized that actors may adhere to justice rules due to their cognitive compliance motive or positive affective motive, which promote prosocial behaviors, or may violate these rules to rectify what they perceive as employee wrongdoing. Importantly, researchers have also identified managerial Robin Hoodism strategies, referring to managers’ unsanctioned use of organizational resources to compensate for unfairness suffered by an employee (Cropanzano et al., 2011). Such strategies are largely understood to reflect a deontic justice motive.

Deontic Justice Enactment: Opening Up New Vistas

While we support this line of research, we argue that the classical “clear-cut distinction [that] differentiates deontic motives from those governed purely by self-interest” (Folger, 2001, p. 5) may limit our considerations of morality and justice. In fact, we observe that the justice literature has largely equated deontic with rule-following and so-called compliance behaviors that “comply with, and do not violate, basic [ethical] rules (…) [and thus] reflect an absence of deviance” (Dasborough et al., 2020, p. 9). In this sense, deontic justice is concerned with proscriptive behaviors reaching minimal moral standards (Treviño et al., 2006). Former conceptualizations of deontic justice have also referred to “requirement-based (moral rule-following) reasons for action” (Cropanzano et al., 2003, p. 1020). Several justice enactment studies have built upon this obligation reasoning (Kleshinski et al., 2021). For example, Brebels et al. (2010) pointed to the motivation of bringing oneself into alignment with one’s “ought” self, and Qin et al. (2018, p. 226) stated that “supervisors ought to treat their subordinates fairly.”

We argue that it is important to reconsider how we use the term “deontic.” If we equate deonance with only compliance, with “thou shalt not,” then we water it down; we might not be able to fully explain fairness enacted for the sake of fairness, fairness enacted to actualize personal convictions in striving towards “inner rightness,” even when the actors risk negative consequences for themselves. As discussed earlier, fair behavior does not stem from only an obligation-driven intention (“morality of obligation,” Fuller, 1969; Van der Burg, 1999); it can also be “beyond the call of duty” and rooted in desire or aspiration (“morality of aspiration,” Fuller, 1969; Van der Burg, 1999) or, in its richest form, in an internal (instead of external) ought. In other words, fairness may include humanistic behaviors and even supererogation.

Thus, deontic justice enactment can grow out of the power to refrain from behaving unethically (proscriptive) and the proactive power to behave ethically (prescriptive) (Dasborough et al., 2020; Janoff-Bulman et al., 2009). Consequently, we draw on two types of prescriptive behaviors—humanistic behaviors and supererogatory behaviors—that, as we argue, complement compliance behaviors to provide a richer and broader definition of deontic justice enactment that includes an aspirational and internal ought instead of only an external obligation (Dasborough et al., 2020). The earliest conceptualizations of justice support our assertions. Aristotle (2009) equated justice with virtue that cannot be surpassed and that is concerned with another’s good (Heyd, 1982). Plato (1992) in turn stated that justice (acting justly) as a virtue is tied “to an internal state [emphasis added] of the person rather than to (adherence to) social norms or to good consequences” (Slote, 2010).

Humanistic behaviors involve prosocial behaviors that enact goodwill towards others, such as supporting or helping acts—for example, helping a new colleague after finishing one’s own work (Dasborough et al., 2020). Humanistic behaviors do not, however, imply personal risk to or major sacrifices by the person engaging in them. Despite contributing to the effective functioning of an organization, these behaviors are neither explicitly required by employment contracts nor directly recognized by formal reward systems (Ilies et al., 2013). Humanistic behaviors involve more than mere compliance with duties, express what an individual “wants to do” or “wants to be,” and thus are discretionary (Dasborough et al., 2020). Supererogatory behaviors move beyond even humanistic behaviors and are understood as the personal freedom to voluntarily sacrifice one’s own personal good for the sake of someone else’s good with no obligation to do so (Heyd, 1982; Mazutis, 2014; Tencati et al., 2020; Urmson, 1958). An example of such behavior may be whistleblowing, as it is not required and involves a personal risk to one’s own career (Dasborough et al., 2020, see also Near & Miceli, 1996).

For our purposes, humanistic and supererogatory behaviors involve managerial behaviors aimed at assuming a proactive role in a specific context (i.e., one’s team, the organization, society at large); they can entail significant personal, emotional, physical, or financial sacrifice or risk. Thus, they can also be called meritorious (Heyd, 1982; Tencati et al., 2020) because they involve doing something “extra.” Doing one’s duty is not particularly praiseworthy; however, going beyond one’s duty as prescribed by the normative context is. Supererogatory behavior is rooted in classical conceptualizations of (nonmandatory) virtue (Dasborough et al., 2020; Pincoffs, 1986), often called “heroic,” and reflects significant extrarole behaviors that achieve moral excellence in seeking to “resist moral compromise” (Green, 1991, p. 78).

Interestingly, as previously mentioned, this type of managerial justice enactment has been recorded in the literature, predominantly under the label of Robin Hoodism, with the explanation that it is an expression of the deontic justice enactment motive (Cropanzano et al., 2011). Indeed, such an unauthorized use of organizational resources to restore justice cannot be explained through moral rule-following; rather, it involves a risk of potential negative consequences for oneself, an aspect that can be captured only through supererogatory behaviors. The choice of Robin Hoodism is made freely by the individual agent, and as it surpasses the requirements of justice in the legal sense, it has also been called “supererogatory justice” (Heyd, 1982, p. 44). Recently, the concept of supererogation has started to permeate research in other fields, such as corporate social responsibility (Tencati et al., 2020), where it has been used to describe voluntary responses to moral obligations, which is normally not the main focus of a business. While the role of supererogation remains undertheorized in the organizational justice literature, we propose that deontic justice enactment, in its richest form, includes the concept of supererogation. What distinguishes supererogatory from compliance and humanistic behaviors is the shift from doing what one “should (not) do” to doing what one “has to do,” reflecting an internal sense of duty and ought. Thus, supererogatory behavior grows not out of an external ought (compliance behavior) or a personal aspiration (humanistic behavior) but out of the individual’s willingness to act upon their moral compass, aimed at sticking to one’s own internal yardsticks. Interestingly, the term “supererogation” first appeared in the Latin version of the New Testament in the parable of the Good Samaritan: “Curam illius habe, et, quodcumque supererogaveris, ego, cum rediero, reddam tibi” (The Latin Vulgate New Testament Bible, 2012, Luke 10:35). This may express the distinction between what one has to do and what one ought to do, as it is one’s duty (such as helping an injured person on the side of the road) and what goes beyond this duty, that is, what is supererogatory (such as paying for that person’s further care).

Proposition 1:

Deontic justice enactment encompasses different types of behaviors: compliance with norms and rules, humanistic (prosocial) behaviors, and supererogatory behaviors.

Interindividual Differences in Deontic Justice Enactment

Justice is considered a fundamental human motive that is primary, “primordial, (…) not conceived of as a means to achieve other goals (…) [and] cannot be reduced or derived from any other motive” (Montada, 2002, p. 49). The more important justice principles are for an individual, the more readily they perceive situations as justice-related and the more often justice concerns are situationally activated and guide their behavior. Furthermore, the stronger an individual’s justice motive is, the more pronounced their emotions resulting from the perception of injustice and the greater their motivation to act in accordance with the motive (Montada & Maes, 2016).

The social justice literature has identified several personality dispositions to capture the “justice motive” and to explain individual differences in the strength of this motive. Prominent examples are the belief in a just world (i.e., the dispositional conviction that people deserve what they get and get what they deserve; e.g., Dalbert, 2009; Rubin & Peplau, 1975), justice sensitivity (Baumert et al., 2013; Schmitt, 1996), and moral identity (Aquino & Reed, 2002). However, more recent research has suggested that none of these trait concepts is a pure indicator of the justice motive: the belief in a just world, for instance, captures not only a concern for justice but also the extent to which the experience of randomness is perceived as aversive (e.g., Schmitt, 1998). A dispositional sensitivity to befallen injustice (i.e., justice sensitivity from a victim’s perspective) captures not only a concern for justice but also a latent fear of being exploited by others (Gollwitzer & Rothmund, 2009; Gollwitzer et al. 2013).

Here, we introduce the concept of moral maturation to the organizational justice literature. We argue that moral maturation is uniquely shaped and predicted by the justice motive because it includes not only the idiosyncratic value of justice for the self but also the ability to act upon the justice motive. In a similar vein, research has shown that Robin Hoodism, expressing the deontic justice motive, is enacted by “high moral identifiers” (Cropanzano et al., 2011, p. 106). It thus stands to reason that stable individual differences in the ability to act upon the deontic justice motive as captured by the concept of moral maturation may help us explain variance in deontic justice enactment.

Moral Maturation

Moral maturation represents the capacity to “elaborate and effectively attend to, store, retrieve, process, and make meaning of morally relevant information” (Hannah et al., 2011a, p. 667). The concept of moral maturation thus goes beyond the seminal but widely criticized moral development conceptualizations of Kohlberg (1981, 1984) and Rest (1986). It comprises three elements that we describe below: moral complexity (knowledge of concepts of morality), metacognitive ability (the “engine” used to process complex moral knowledge), and moral identity (individuals’ knowledge of themselves as moral actors).

Moral Complexity

First, individuals differ in the complexity of their mental representations of various domains of knowledge depending on their breadth of experience and learning across their lifespan (Hannah et al., 2011a; Schroder et al., 1967; Streufert & Nogami, 1989), including in the moral domain (Narvaez, 2010; Swanson & Hill, 1993). Greater complexity in a specific domain leads to more differentiated and richly connected mental representations, allowing a person to process information in greater depth and with more elaboration and to apprehend paradoxical or moral tensions (Hannah et al., 2011a; Rafaeli-Mor & Steinberg, 2002; Streufert & Nogami 1989; Voronov & Yorks, 2015). The distinctive dimensions that individuals use to organize and make meaning of their experiences strongly impact how they make decisions and behave and are thus of importance in the motive/enactment relationship.

For example, the higher an individual’s moral complexity is, the more able they are to discriminate information and develop various moral “realities” that can be compared and connected. As a result, the individual can thoroughly process information and achieve greater coherence when faced with moral conflicts (Hannah et al., 2005; Hannah et al., 2011a; Streufert & Nogami 1989; Werhane, 1999). Consequently, individuals with high moral complexity can draw upon richer “negative” expertise, helping them grasp what actions not to take when faced with morally tense situations.

Metacognitive Ability

However, an assessment of moral complexity alone is insufficient for explaining variance in individuals’ moral maturation (Hannah et al., 2011a; Narvaez, 2010). A high level of complexity is “like fuel without an engine to process that fuel” (Hannah et al., 2011a, p. 669); the individual also needs the capacity, the “engine,” to deeply process complex moral knowledge. Metacognitive ability, as a second dimension of moral maturation, is the mental capacity required to process moral issues in depth and encapsulates monitoring and regulatory cognitive processes (Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009; Hannah et al., 2011a), hence serving both the self-referential and executive control functions that are essential for moral cognition. Interdisciplinary studies indicate a clear distinction between general cognitive ability and metacognitive ability, with the former referring to the general capacity to reason and solve problems and the latter referring to the ability to regulate and control cognition as these reasoning processes unfold (Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009; Hannah et al., 2011a).

We suggest that higher levels of metacognitive ability—in conjunction with moral complexity and moral identity—strengthen deontic justice enactment because complex moral dilemmas require the capacity to select from, access, and modify moral knowledge and apply elaborative reasoning to a specific moral dilemma to achieve a sense of logical coherence (Hannah et al., 2011a). Metacognitive ability functions as executive control over these processes, determining what a person recalls and attends to (Metcalfe & Shimamura, 1994). In line with Hannah et al. (2011a), we suggest that the distinction between moral complexity and metacognitive ability allows us to understand how individuals process ethical issues that force them to address multiple competing values, what information is used in making judgments, how accurately information is assessed, what emotions are elicited or whether all possible aspects of a moral dilemma are considered when enacting—or not enacting—deontic justice. Both moral complexity and metacognitive ability are needed for moral maturation.

Moral Identity

In addition to moral complexity and metacognitive ability, moral maturation includes an individual’s knowledge of themself as a moral actor—their moral identity (Aquino et al., 2009; Blasi, 1983, 1984; Erikson, 1964). Self-identity determines the most accessible knowledge structures individuals have about themselves and strongly influences the ways in which they regulate their behaviors (Hannah et al., 2011a; Lord & Brown, 2004; Schwabe & Gollwitzer, 2020). In Erikson’s (1964) view, identity is rooted in the core of one’s being, encompasses being true to oneself in action, and is associated with respect for one’s own understanding of reality. Similarly, Blasi (1983) introduced his Self-Model of moral action based on the finding that moral judgment does not reliably predict moral action; rather, moral action is filtered through a set of calculations that implicate the very integrity of the self. Although moral structures serve to appraise the moral landscape, they do not directly generate action but depend on whether moral considerations are deemed essential and core to one’s personal identity. Moral identity is thus considered to function as a self-regulatory mechanism (Blasi, 1984) and as a cognitive schema that people hold about their moral character (Aquino et al., 2009). While moral complexity and metacognitive ability reflect the degree of elaboration of moral knowledge, moral identity guides these processes through an internal evaluation process (Bandura, 1999, 2002) and thereby contributes to moral maturation (Hannah et al., 2011a).

Highly complex individuals without a strong moral identity might, for example, justify moral disengagement when such processing is not guided by self-standards. Moral identity can thus be considered an interpretive structure that mediates significant intrapersonal processes such as information processing, affect, or motivation as well as various interpersonal processes such as social perception, behavior, or response to feedback (Hogg et al., 1995; Markus & Wurf, 1987) and is motivated by the consistency principle (Erikson, 1964). Taylor (1989) noted that individuals’ identity is rooted in things that are relevant to them and based on the formation of evaluations of what is right and wrong. Being connected to something seen as worthy is crucial to being a functional moral agent (Narvaez & Lapsley, 2010).

In organizational behavior research in general and in justice research specifically, moral character has been studied mostly through the lens of moral identity (Aquino & Reed, 2002). Many studies have treated moral identity as an isolated (Hannah et al., 2011a) and cross-situationally stable construct (Blasi, 1984; Hardy & Carlo, 2011). This approach, however, ignores dynamic structures such as roles, goals, motivation, affect, or autobiographical narratives (Hannah et al., 2011a; Hill & Roberts, 2010; Lord et al., 2011). While the view of moral identity as a singular identity structure still dominates much of the organizational behavior research, a multifaceted, cross-identity perspective is currently developing (Hannah et al., 2011a, 2020; Woolfolk et al., 2004). While this prevailing perspective understands moral identity as more or less central to an individual’s overall identity (Aquino et al., 2009), it does not allow us to explain the variance in people’s moral behavior across situations. We suggest that the multifaceted perspective that builds on self-complexity theory (Hannah et al., 2011a) helps us understand the variance in people’s fairness motives and in their ability to act upon them. This multifaceted lens also acknowledges that individuals have multiple selves, such as parent, team leader, colleague, or brother, rather than being a unified whole (Markus & Wurf, 1987). However, people with a high level of moral maturation do not possess separate moral identities for each of their “selves”; their moral compass is highly salient across situations and thus is less volatile across different “selves” (Hannah et al., 2011a)

Taken together, we consider that moral maturation consisting of moral complexity, metacognitive ability, and moral identity, is a particularly relevant yet underexplored framework for understanding individual differences in people’s, and in our case specifically in managers’, deontic justice enactment. Based on the above discussion, we argue that moral maturation is predicted by the deontic justice motive.

Proposition 2:

A manager’s deontic justice motive predicts their level of moral maturation, consisting of moral complexity, metacognitive ability, and moral identity

Bridging moral maturation and deontic justice enactment, we further propose that high levels of moral maturation lead to deontic justice enactment in its richest form, that is, supererogatory behavior.

Proposition 3:

Deontic justice enactment in its richest form (i.e., supererogatory behavior) requires a high level of moral maturation.

Situation Strength and Person Strength

People differ not only in their characteristic levels of behavior across situations but also in their characteristic levels of behavioral variability across situations (Dalal et al., 2015). Regarding morality, it is not only the manager’s singular behavior that matters but also the extent to which moral behavior is consistent across different contexts, situations, and interaction partners (Johnson et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2018). After all, individuals’ thinking about right and wrong and their subsequent actions are highly susceptible to contextual influences that govern judgments about what to do in complex, ambiguous, morally tense situations (Berti et al., 2021; Dasborough et al., 2020; de los Reyes et al., 2017).

We thus build on recent calls for research on the relevance of time and (in)variance in the justice domain (Hausknecht et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2018) and draw on Mischel’s (1973) seminal work on situation strength that asked under what conditions personality traits are more (vs. less) predictive of people’s actual behaviors. Ensuing research has suggested that inconsistency among people’s attitudes and behaviors in specific contexts occurs because social contexts can create considerable psychological pressure to conform (Cooper & Withey, 2009). In operationalizing situation strength, Meyer et al. () presented a four-faceted conceptualization comprising clarity (the extent to which cues regarding work-related responsibilities are available and understandable), consistency (the extent to which these cues are compatible with each other), constraints (the extent to which an individual’s freedom of decision and action is limited by external forces), and consequences (the extent to which decisions or actions have essential implications for any relevant party involved). Situation strength can thus be defined as “implicit or explicit cues provided by external entities regarding the desirability of potential behaviors” (Meyer et al., 2010a, 2010b, p. 122). An important, more complex perspective has the potential to enrich our understanding of deontic justice enactment, as it investigates not only whether individual factors predict justice enactment but also under what conditions they do so (Meyer et al., 2010a, 2010b; Mischel, 1973).

Situation strength can reduce individual variance in observable behaviors through strong local norms (e.g., high pressure to perform in an ambitious team), situational demands (e.g., time pressure to complete a work assignment), conventions or rituals, or extraordinary stressors (e.g., being provoked by an opponent; see Marshall & Brown, 2006; Schmitt et al., 2013). Organizational settings are widely recognized to be strong situations (Meyer et al., 2010a, 2010b). This strength manifests in the communication of work-related responsibilities, company policies, strategic priorities, behavioral monitoring systems, and performance-contingent rewards/punishments. Such norms—whether explicitly codified or implicitly transmitted—also guide the adjudication of what to do in complex, ambiguous, morally tense situations and restrict the expression of individual differences by conveying how one ought to act (Berti et al., 2021; de los Reyes et al., 2017).

Mischel (1973) explicitly focused on behavioral variability (Cooper & Withey, 2009; Keeler et al., 2019) instead of predicting attitudes, “except insofar as the affect or cognition is exemplified behavior” (Keeler et al., 2019, p. 1490). This is a noteworthy distinction even though a multitude of studies have investigated attitudinal (affective or cognitive) outcome variables (Keeler et al., 2019). External pressures may force people to comply behaviorally, but their attitudes are more resistant to change and are characterized by greater stability (Staw & Ross, 1985). While the behavioral expression of cognition or attitudes may appear to change at first glance (e.g., looking happy at your cousin’s wedding), internal attitudes may remain unchanged regardless of the situation (e.g., you dislike your cousin) (Keeler et al., 2019). To understand the relationship between the deontic justice motive and enactment, this focal point of behavioral variability is thus essential.

Intraindividual Variability and Consistency in Deontic Justice Enactment

The concept of “person strength” introduced above reflects the degree of intraindividual variability across situations; strong persons are those whose personality-congruent behavior varies less across time and situations (Schmitt et al., 2013). Person strength itself is a disposition, a “meta-trait” (Baumeister & Tice, 1988; Bem & Allen, 1974). Analogous to situation strength, person strength provides a new lens for understanding both within-person variability and within-person stability (Dalal et al., 2015). Research has suggested three approaches to quantifying person strength. First, person strength (or “consistency”) can be measured directly via self-reports (Bem & Allen, 1974), but this approach is psychometrically problematic because self-reports require that people have a clear (and interindividually consistent) mental representation of what “consistency” means and how it manifests. Second, person strength (“traitedness”) can be inferred from the degree of variability across situations or contexts (Baumeister & Tice, 1988; Britt, 1993), regardless of what is measured (e.g., attitudes, behavior), how it is measured (e.g., objectively/unobtrusively, subjectively/reactively), and whether the data source is the target person themself or a third party. Third, person strength can be inferred from the trait measure itself: strong persons tend to have more extreme trait measures on a scale than weak persons (Blum et al., 2018; Schmitt et al., 2013).

Adopting the latter of these three perspectives, we propose that persons with high levels of moral maturation can be considered “strong.” Supererogatory behavior, as the richest form of deontic justice enactment, might seem necessary in morally tense situations, but not everyone can engage in such behavior. It can be expected only from those who subjectively feel the commitment to engage in it and who are equipped with the necessary strength. Specifically, we posit that morally highly mature persons are those who display supererogatory behavior even in strong situations—that is, even in the presence of strong norms or incentives that would guide them to behave in a manner that is incongruent with their inner compass. In this sense, moral maturation is a concept that not only captures individual differences in the deontic justice motive but also helps explain individual differences in the extent to which individuals’ deontic justice enactment varies across situations (i.e., person strength).

Strong situations with inherent moral conflict typically present individuals with competing values and choices (Rhodes et al., 2010). The literature indicates that in areas where the self is less “invested” (Hannah et al., 2011a), individuals who are low in moral maturation—whom we may also call “weak persons”—are more susceptible to contextual influences. Especially in times of difficult organizational changes, when managers are forced to make and implement tough decisions—such as layoffs or contract terminations caused by cost-cutting plans or efficiency programs—the gap between an individual’s deontic justice motive and subsequent behavior is likely to widen, and strong situational pressures may easily override an actor’s fairness intentions (Camps et al., 2022; Jennings et al., 2015; Jordan et al., 2011; Zwank et al., 2022). In contrast, a “strong,” highly morally mature person—a more complex person with greater metacognitive ability and moral identity—can draw from a broader base of moral content and better tailor and consciously direct their active self across a broad range of situations (Hannah et al. 2009, 2011a; Lord et al., 2011). We therefore propose that persons high in moral maturation are “strong” persons who behave in accordance with their inner compass despite strong situational pressures to do otherwise. Thus, high moral maturation leads to consistent supererogatory behaviors; low moral maturation, by contrast, may also lead to deontic justice enactment, but this enactment more likely reflects rule compliance and/or humanistic behaviors.

Proposition 4:

When moral maturation is high, the deontic justice motive manifests in consistent supererogatory behavior across situations, even though situational norms or incentives would prescribe different behavior.

Proposition 5:

When moral maturation is low, the deontic justice motive manifests in compliance and humanistic behavior that may vary considerably based on situational norms or incentives prescribing certain behavior.

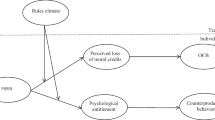

Our model (Fig. 1) depicts the theorized relationships between the deontic justice motive, moral maturation, situation strength, and deontic justice enactment.

In summary, we illustrate the interaction between person strength and situation strength in what we call the “deontic justice enactment continuum.” This illustration suggests that people who are high in moral maturation are more likely to enact deontic justice, including supererogatory behaviors, and that their actions are not affected by the strength of the situation, whereas those who are low in moral maturation are more strongly influenced by the strength of the situation.

Discussion

Contributing to an emerging yet fragmented body of research on organizational justice enactment and its antecedents, we have drawn on accounts of the deontic justice motive, supererogation, moral maturation, and person strength as well as situation strength to explain the nature of deontic justice enactment and why managers at times do—and at times do not—enact organizational justice for deontic reasons (see Fig. 1). In doing so, we make three contributions to the literature, provide avenues for future research, and offer practical implications for building good organizations by design and not by chance. We discuss these aspects in the following.

Theoretical Contributions

Our theorizing offers specific suggestions for broadening and strengthening the emerging literature on justice enactment. First, our research extends the current conceptualization of deontic justice enactment. To date, the few previous studies have conceptualized deontic justice enactment as compliance behaviors concerned with reaching minimal moral standards (Treviño et al., 2006) or “requirement-based (…) reasons for action” (Cropanzano et al., 2003, p. 1020). We consider that merely fulfilling requirement-based minimal moral standards is insufficient for fully understanding and explaining fairness enacted for its own sake. We posit that “deontic” justice enactment not only stems from an obligation-driven intention but also can go beyond the call of duty, as it is rooted in a personal (nonutilitarian) desire for or aspiration to morality (Fig. 2).

To provide a richer definition of deontic justice enactment, we draw on two focal behavioral categories, humanistic behaviors (prosocial behaviors enacting goodwill towards others) and supererogatory behaviors (personal freedom to voluntarily sacrifice one’s own personal good for the sake of someone else’s good, with no obligation to do so; see Dasborough et al., 2020), aimed at achieving moral excellence and seeking to “resist moral compromise” (Green, 1991, p. 78). We thus argue that the classical understanding of deontic justice enactment as an ought (Folger, 2001) or as requirement-based moral rule-following (Cropanzano et al., 2003) should be extended to cover humanistic (prosocial) and virtuous supererogatory behaviors. We therefore argue that deontic justice enactment, in its richest form, is captured by the concept of supererogation. Supererogatory behavior stems from the disposition to stick to one’s own internal yardstick, one’s own inner rightness, or one’s own inner compass instead of external oughts that guide compliance behaviors. Second, our study identifies a concept that can capture the deontic justice motive and individual differences in the strength of this motive: moral maturation. We argue that the deontic justice motive predicts moral maturation, consisting of moral complexity, metacognitive ability, and moral identity, and thus explains variance in deontic justice enactment above and beyond other traits. Consequently, deontic justice enactment in its richest form (i.e., supererogatory behavior) requires a high level of moral maturation that is derived from a strong deontic motive.

Third, scholars have only recently acknowledged that justice enactment does not emerge in a vacuum but is a highly contextualized phenomenon (Camps et al., 2022; Diehl et al., 2021; Sherf et al., 2019). Actors are exposed to contextual forces that foster or inhibit specific behaviors (un)authorized by the (often unwritten) norms of an organization (Camps et al., 2022). Building upon the notion that such strong situations reduce the predictive power of individual differences for behavior, we propose that persons who are particularly morally mature consistently act upon their motives regardless of the strength of the situation. Morally mature persons are therefore “strong” persons (Dalal et al., 2015; Schmitt et al., 2013). In that vein, we can conceptualize deontic justice enactment in its highest or “purest” form as consistent supererogatory behavior across situations. In other words, deontic justice enactment can be defined as the behavior of strong (i.e., morally mature) persons in strong situations, and the deontic justice motive manifests in consistent supererogatory justice behavior, even though situational norms or incentives would prescribe behaving differently.

Limitations and Future Research

Our theorizing offers a rich and promising future research agenda beyond empirical work to assess our propositions. First, we acknowledge that doing what is right in strong situations also requires overcoming social pressures (Bandura, 2002; Hannah et al., 2013) and thus moral courage; these aspects were explicitly excluded from our theorizing, which took a cognitive approach. Moral courage enables an individual to proactively take action that exceeds moral norms at personal risk or sacrifice (Hannah et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2009) and represents a self-regulatory capacity to engage in exemplary action or pursue actions even in the face of ethical challenges, such as strong situations (Bandura, 2002; Hannah et al., 2011a). While we recognize moral identity—one of the three key components of moral maturation—as unique in that it drives both moral cognition and one's motivation to act, the concept of moral courage warrants further research, especially with regard to humanistic and supererogatory behaviors.

Second, although we have referred to the role of emotions in justice enactment, a detailed consideration of affect and moral emotions has been beyond the scope of this study. However, in line with Scott et al. (2009) actor-focused model, we acknowledge the role of these emotions in deontic justice enactment. While it has been widely accepted that moral emotions such as anger, moral outrage, regret, shame, guilt, embarrassment, and schadenfreude (Dasborough & Harvey, 2017; Walker & Jackson, 2017) influence the link between moral motives and moral behavior (Lindenbaum et al., 2017), research has emphasized that individuals differ in the emergence and experience of these moral emotions (Haidt, 2003). Studies have further assumed that moral emotions are related to the capacity to self-regulate and to choose one’s own moral path, can punish or reinforce behaviors, and can function as an “emotional barometer” (Tangney et al., 2007). For instance, moral outrage arises when a person perceives an event as morally unacceptable and may show a tendency to rectify a moral wrong (Lindenbaum et al., 2017). Thus, moral emotions may either mediate or moderate the relationship between the deontic motive and deontic justice enactment. We thus recommend that future studies extend our research by adopting a moral emotions perspective.

Third, we deliberately decided against discussing a topic that was heatedly debated in the morality and social justice literature in the 1990s and 2000s: the distinction between two (gender-specific) types of ethics, an “ethics of justice” (focusing on equal or equitable treatment, impartiality, objectivity, etc.) and an “ethics of care” (focusing on maintaining harmony, adherence to the need principle, and compassion/empathy; see, e.g., Gilligan, 1982a). More specifically, Gilligan (1982b) proposed gender differences such that while both men and women use both orientations, women more strongly emphasize care when making moral decisions, whereas men tend to prioritize justice rules and the rational approach they allow for (Ford & Lowery, 1986; Gilligan & Attanucci, 1988). Other scholars, however, radically dismiss dilemmas between the ethics of care and the requirements of justice (e.g., Barry, 1995). Our arguments and extension of the scope of deontic justice give rise to the question of whether the commonly postulated hierarchy (e.g., Noddings’ portrayal of care as superior to justice from 1999) or juxtaposition (Botes, 2000) of the two concepts remains meaningful. Taking a “middle ground” between the two camps, we acknowledge that both justice and care have a place in decision-making (Gilligan, 1982b). While we do not consider the definition of gender-specific concepts of moral maturation or deontic justice to be the primary research gap, we encourage further studies to consider the intertwined relationship between care and justice, especially with reference to deontic justice.

Fourth, we call for a thorough investigation of contextual influences on justice enactment and an examination of how congruence between specific personological factors and environmental characteristics is linked to different justice motives, such as instrumental, relational, deontic, and uncertainty reduction interests. For example, a rich body of research has explored the impact of congruence between individual and organizational values, a concept called person-organization (P-O) fit (see, e.g., Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). We thus assume that congruence between an organization’s ethical climate—commonly classified into five types: instrumental, caring, independence, law and code, and rules (Victor & Cullen, 1988)—and an individual’s moral maturation is consistently related to enacting, or not enacting, justice and could be linked to various justice motives. For instance, adults who are low in moral maturation may find it easier to fit into strong climates, while individuals who are high in moral maturation, and thus have a strong deontic motive, might fit best in independence climates. Interestingly, P-O fit has been shown to influence various organizational outcomes, is negatively related to turnover intentions, and is significantly positively related to job satisfaction (Ambrose et al., 2008). It thus stands to reason that the current justice literature could benefit from conceptualizations and models that consider and integrate contextual factors to a greater extent than it is currently done.

Practical Implications

Justice is considered to be a primary, “primordial” motive (Montada, 2002), and just behavior benefits not only the recipients but also the actors. Studies have provided evidence that acting fairly for deontic reasons and displaying socially justified and morally sound behavior leads to positive effects, such as positive emotions (Johnson et al., 2014) or social recognition (Folger & Cropanzano, 2010). In contrast, research on the effects of injustice enactment points to high levels of interpersonal distress for actors, threats to themselves, and self-protective responses, such as exit or avoidance (Molinsky & Margolis, 2005). Injustice enactment thus appears harmful not only to the recipients but also to the actors.

Although we have argued that the deontic motive is a key antecedent to moral maturity, moral maturation is also malleable (Hannah et al., 2011a), intensifying the need for organizations to support its development. On the one hand, research on moral pedagogy emphasizes that organizations can cultivate managers’ moral maturation capacity and ability to deal with justice dilemmas in strong situations by exploiting experiential approaches to education (e.g., Berti et al., 2021) that integrate normative, behavioral, and social determinants. Specific moral discourses and development programs that expose individuals to moral conflicts and thereby build new associations between concepts held in their mental representations can systematically increase the level of complexity and therefore moral maturation (Hannah et al., 2011a). Similarly, moral courage, the concept for which we call for further research on the motive-enactment relationship to deontic justice, is viewed as malleable (Hannah et al., 2011b, 2013) and can be enhanced by training (Jonas et al., 2007) or social learning processes (Worline et al., 2002).

On the other hand, research has suggested that subtle contextual cues can influence individuals’ moral judgments and day-to-day decisions more than formalized codes of conduct (Leavitt et al., 2016; Reynolds, 2006). Research on multiple occupational identities (Leavitt et al., 2012) has shown that implicitly held knowledge structures can be triggered by contextual cues that activate moral obligations and influence actors’ “situated moral judgments” in a predictable and meaningful manner. Consequently, deontic justice enactment, and specifically supererogatory behavior, can be fostered or inhibited through certain subtle contextual cues in managers’ work environment and routine tasks.

Managers in organizations are often forced to cause harm to their employees in the service of achieving some perceived greater good, such as laying off subordinates to improve organizational performance (Molinsky & Margolis, 2005). This raises the paradoxical and important question of whether short-term orientation, which characterizes many organizations, indeed promotes individuals consistently enacting organizational justice for the sake of justice and displaying supererogatory behaviors and thereby allows for “corporate samaritans.” Such short-term orientation is probably more likely to promote the career development of “tough” managers, who ensure the effective functioning of the business regardless of justice considerations. Indeed, if a manager’s morality is too “idealistic,” the risk might be that they are seen as overlooking other managers’ duties and violating performance norms (see also Camps et al., 2022). The inescapable questions are thus as follows: When is it “bad” to be “good,” and further, when is it “good” to be “bad?”.

Conclusion

Behavior in organizations is often restricted by strong organizational norms (Mowday & Sutton, 1993; Treviño et al., 2006). Hence, people are not always able to act upon their deontic justice motive. While a plethora of research has investigated individuals who lack or ignore moral concerns, we are intrigued by those largely underresearched individuals who are able to break through the blinders imposed on them, resist moral compromise, and enact justice as a moral virtue. Moreover, they do not do this out of mere compliance or requirement-based moral rule-following; rather, they go beyond the call of duty and, in their richest form, express themselves through supererogatory behaviors. By shedding light on the etiology of these individuals, we have argued that an individual’s deontic justice motive predicts their level of moral maturation and that person strength (i.e., a high level of moral maturation) overrides situation strength and thus predicts supererogatory behavior—genuine deontic justice enactment—even in the face of situational constraints. Cui bono? For all and none—just because we believe in “corporate samaritans,” those who go across the road to the wounded man just because they want to.

Data Availability

This paper is theoretical and does not involve the use of any empirical data.

References

Ambrose, M. L., Arnaud, A., and Schminke, M. (2008). Individual moral development and ethical climate: The influence of person-organization fit on job attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(3), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9352-1

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A., Felps, W., & Lim, V. K. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 123–141.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1423–1440.

Aristotle. (2009). Nicomachean ethics. Translated by W.D. Ross, revised by J. Ackrill and J. Urmson. Oxford University Press.

Babiak, P. (1995). When psychopaths go to work: A case study of an industrial psychopath. Applied Psychology, 44(2), 171–188.

Bamberger, P. A. (2008). From the Editors. Beyond contextualization: Using context theories to narrow the micro-macro gap in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), 839–846.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 193–209.

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31, 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724022014322

Barry, B. (1995). Justice as impartiality. Clarendon Press.

Batson, C. D., & Shaw, L. L. (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2, 106–123.

Baumeister, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (1988). Metatraits. Journal of Personality, 56(3), 571–599.

Baumert, A., Rothmund, T., Thomas, N., Gollwitzer, M., & Schmitt, M. (2013). Justice as a moral motive. Belief in a just world and justice sensitivity as potential indicators of the justice motive. In K. Heinrichs, F. Oser, & T. Lovat (Eds.), Handbook of moral motivation. Theories, models, applications (pp. 159–180). Sense Publishers.

Beauchamp, T. (2019). The principle of beneficence in applied ethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://stanford.library.sydney.edu.au/archives/fall2021/entries/principle-beneficence/.

Bem, D. J., & Allen, A. (1974). On predicting some of the people some of the time: The search for cross-situational consistencies in behavior. Psychological Review, 81(6), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037130

Berti, M., Jarvis, W., Nikolova, N., & Pitsis, A. (2021). Embodied phronetic pedagogy: Cultivating ethical and moral capabilities in postgraduate business students. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 20(1), 6–29.

Blasi, A. (1983). Moral cognition and moral action: A theoretical perspective. Developmental Review, 3, 178–210.

Blasi, A. (1984). Moral identity: Its role in moral functioning. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (Eds.), Morality, moral behavior and moral development (pp. 128–139). Wiley.

Blum, G. S., Rauthmann, J. F., Göllner, R., Lischetzke, T., & Schmitt, M. (2018). The nonlinear interaction of ¨person and situation (NIPS) model: Theory and empirical evidence. European Journal of Personality, 32(3), 286–305. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2138

Blum, G., & Schmitt, M. (2017). The nonlinear interaction of person and situation (NIPS) model and its values for a psychology of situations. In J. F. Rauthmann, R. A. Sherman, & D. C. Funder (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of psychological situations (pp. 1–17). Oxford University Press.

Boddy, C. R. (2011). The corporate psychopaths theory of the global financial crisis. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 255–259.

Botes, A. (2000). A comparison between the ethics of justice and the ethics of care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(5), 1071–1075.

Brebels, L., De Cremer, D., Van Dijke, M., & Van Hiel, A. (2010). Fairness as social responsibility: A moral self-regulation account of procedural justice enactment. British Journal of Management, 22, 47–58.

Britt, T. W. (1993). Metatraits: Evidence relevant to the validity of the construct and its implications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(3), 554–562. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.3.554

Brockner, J., Wiesenfeld, B., Siegel, P., Bobocel, D. R., & Liu, Z. (2015). Riding the fifth wave: Organizational justice as dependent variable. Research in Organizational Behavior, 35, 103–121.

Camps, J., Graso, M., & Brebels, L. (2022). When organizational justice enactment is a zero sum game: A trade-off and self-concept maintenance perspective. Academy of Management Perspectives, 36(1), 30–49.

Cappelli, P., & Sherer, P. D. (1991). The missing role of context in OB: The need for a meso-level approach. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, 13 (pp. 55–110). JAI Press.

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (1993). When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence. Psychological Inquiry, 4, 247–271.

Cohen, S. (2013). Forced supererogation. European Journal of Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejop.12023

Colquitt, J. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386.

Colquitt, J., Conlon, D., Wesson, M., Porter, C., & Ng, K. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425–445.

Colquitt, J., Greenberg, J., & Zapata-Phelan, C. (2005). What is organizational justice? A historical overview. In J. Greenberg & J. Colquitt (Eds.), The handbook of organizational justice (pp. 3–56). Erlbaum.

Cooper, W. H., & Withey, M. J. (2009). The strong situation hypothesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 62–72.

Cropanzano, R., Goldman, B., & Folger, R. (2003). Deontic justice: The role of moral principles in workplace fairness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 1019–1024.

Cropanzano, R., Massaro, S., & Becker, W. J. (2017). Deontic justice and organizational neuroscience. Journal of Business Ethics, 144, 733–754.

Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D., Mohler, C., & Schminke, M. (2001). Three roads to organizational justice. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 20, 1–113.

Cropanzano, R., Stein, J. H., & Nadisic, T. (2011). Social justice and the experience of emotion. Routledge.

Dalal, R. S., Meyer, R. D., Bradshaw, R. P., Green, J. P., Kelly, E. D., & Zhu, M. (2015). Personality strength and situational influences on behavior: A conceptual review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 41(1), 261–287.

Dalbert, C. (2009). Belief in a just world. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 288–297). The Guilford Press.

Dasborough, M. T., Hannah, S. T., & Zhu, W. (2020). The generation and function of moral emotions in teams: An integrative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(5), 433–452.

Dasborough, M., & Harvey, P. (2017). Schadenfreude: The secret joy of another’s misfortune. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(4), 693–707.

De los Reyes, G., Kim, T. W., & Weaver, G. R. (2017). Teaching ethics in business schools: A conversation on disciplinary differences, academic provincialism, and the case for integrated pedagogy. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 314–336.

Diehl, M. R., Fortin, M., Bell, C., Gollwitzer, M., & Melkonian, T. (2021). Uncharted waters of justice enactment—Venturing into the social complexity of doing justice in organizations Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(6), 699–707.

Diehl, M.-R., Patient, P., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2013). Bearers of bad news: The manager’s perspective on direct involvement in layoffs. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2013, 14346.

Diehl, M.-R., Richter, A., & Sarnecki, A. (2018). Variations in employee performance in response to organizational justice: The sensitizing effect of socioeconomic conditions. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2375–2404.

Dinić, B. M., & Wertag, A. (2018). Effects of dark triad and HEXACO traits on reactive/proactive aggression: Exploring the gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 123, 44–49.

Doh, J. P., & Stumpf, S. A. (2005). Handbook on responsible leadership and governance in global business. Edward Elgar.

Dunlosky, J., & Metcalfe, J. (2009). Metacognition. Sage Publications.

Elovainio, M., van den Bos, K., Linna, A., Kivimäki, M., Ala-Mursula, L., Pentti, J., & Vahtera, J. (2005). Combined effects of uncertainty and organizational justice on employee health: Testing the uncertainty management model of fairness judgments among Finnish public sector employees. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 2501–2512.

Erikson, E. (1964). Insight and responsibility. Norton.

Feldman, F. (1986). Doing the best we can. Reidel.

Fleeson, W. (2004). Moving personality beyond the person-situation debate: The challenge and the opportunity of within-person variability. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00280.x

Folger, R. (1998). Fairness as a moral virtue. In M. Schminke (Ed.), Managerial ethics: Moral management of people and processes (pp. 13–34). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Folger, R. (2001). Fairness as deonance. In S. Gilliland, D. Steiner, & D. Skarlicki (Eds.), Research in social issues in management (pp. 3–33). Information Age.

Folger, R. and Cropanzano, R. (2010) Social hierarchies and the evolution of moral emotions. In: Schminke M (ed.) Managerial Ethics: Managing the Psychology of Morality (pp. 207–234) Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ.

Folger, R., Cropanzano, R., & Goldman, B. (2005). Justice, accountability, and moral sentiment: The deontic response to “foul play” at work. In J. Greenberg & J. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 215–245). Erlbaum.

Folger, R., & Skarlicki, D. (2001). Fairness as a dependent variable: Why tough times can lead to bad management. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: From theory to practice (pp. 97–118). Erlbaum.

Ford, M. R., & Lowery, C. R. (1986). Gender differences in moral reasoning: A comparison of the use of justice and care orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(4), 777.

Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., & McDaniel, M. A. (2012). A meta-analysis of the Dark Triad and work behavior: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 557–579.

Fuller, L. L. (1969). The morality of law. Book Crafters.

Funder, D. C. (2006). Towards a resolution of the personality triad: persons, situations and behaviors. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.003

Fyke, J. P., & Buzzanell, P. M. (2013). The ethics of conscious capitalism: Wicked problems in leading change and changing leaders. Human Relations, 66(12), 1619–1643.

Giacalone, R. A., & Greenberg, J. (1997). Antisocial behavior in organizations. Sage.

Gilligan, C. (1982a). New maps of development: New visions of maturity. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(2), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb02682.x

Gilligan, C. (1982b). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

Gilligan, C., & Attanucci, J. (1988). Two moral orientations: gender differences and similarities. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 34(3), 223–237.

Glenn, A. L., & Sellbom, M. (2015). Theoretical and empirical concerns regarding the dark triad as a construct. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29(3), 360–377.

Gollwitzer, M. and Rothmund, T. (2009). When the need to trust results in unethical behavior: The sensitivity to mean intentions (SeMI) model. Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making, 135–152

Gollwitzer M., Rothmund T., and Süssenbach P. (2013). The sensitivity to mean intentions model: Basic assumptions, recent findings, and potential avenues for future research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12041

Graso, M., Camps, J., Schulz, N., & Brebels, L. (2019). Organizational justice enactment: An agent-focused review and path forward. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 103296.

Green, R. M. (1991). When is “everyone’s doing it” a moral justification? Business Ethics Quarterly, 1(1), 75–93.

Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, and H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.),Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852-870). Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & May, D. R. (2011a). Moral maturation and moral conation: A capacity approach to explaining moral thought and action. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 663–685.

Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2011b). Relationships between authentic leadership, moral courage, and ethical and pro-social behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21, 555–578. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201121436

Hannah, S. T., Lester, P. B., and Vogelgesang, G. R. (2005). Moral leadership: Explicating the moral component of authentic leadership. Authentic leadership theory and practice: Origins, effects and development, 3, 43–81.

Hannah, S. T., Schaubroeck, J. M., Peng, A. C., Lord, R. G., Trevino, L. K., Kozlowski, S. W., & Doty, J. (2013). Joint influences of individual and work unit abusive supervision on ethical intentions and behaviors: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 579–592.

Hannah, S. T., Thompson, R. L., & Herbst, K. C. (2020). Moral identity complexity: Situated morality within and across work and social roles. Journal of Management, 46(5), 726–757.

Hannah, S. T., Woolfolk, R. L., and Lord, R. L. (2009). Leader self-structure: A framework for positive leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 269–290

Hart, D., Atkins, R., & Ford, D. (1998). Urban America as a context for the development of moral identity in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 54, 513–530.

Hausknecht, J. P., Sturman, M. C., & Roberson, Q. M. (2011). Justice as a dynamic construct: Effects of individual trajectories on distal work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 872–880.

Heyd, D. (1982). Supererogation: Its status in ethical theory. Cambridge University Press.

Heyd, D. (2019). Supererogation. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Online. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/supererogation/.

Hill, P. L., & Roberts, B. W. (2010). Propositions for the study of moral personality development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 380–383.

Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., and White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social psychology quarterly, 255–269.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. Harcourt.