Being good is easy, what is difficult is being just.

(Victor Hugo).

Abstract

Managers tasked with organizational change often face irreconcilable demands on how to enact justice—situations we call justice conundrums. Drawing on interviews held with managers before and after a planned large-scale change, we identify specific conundrums and illustrate how managers grapple with these through three prototypical paths. Among our participants, the paths increasingly diverged over time, culminating in distinct career decisions. Based on our findings, we develop an integrative process model that illustrates how managers grapple with justice conundrums. Our contributions are threefold. First, we elucidate three types of justice conundrums that managers may encounter when enacting justice in the context of planned organizational change (the justice intention-action gap, competing justice expectations, and the justice of care vs. managerial-strategic justice) and show how managers handle them differently. Second, drawing on the motivated cognition and moral disengagement literature, we illustrate how cognitive mechanisms coalesce to allow managers to soothe their moral (self-) concerns when grappling with these conundrums. Third, we show how motivated justice intentions ensuing from specific justice motives, moral emotions, and circles of moral regard predict the types of justice conundrums managers face and the paths they take to grapple with them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Middle and line managers are required to play multiple roles during the implementation of organizational change, from diagnosis and planning to the management of emotions and resistance (Bryant & Stensaker, 2011; Huy, 2001; Huy et al., 2014; Rosenbaum et al., 2018; Wooldridge et al., 2008). Planned change processes that imply restructuring or downsizing in particular require managers to juggle competing responsibilities and conflicting priorities (Huy, 2001). Moreover, the uncertainty inherent in organizational change is bound to heighten stakeholders’ attention to organizational justice (Lind and Van den Bos 2002). Only recently have researchers noted that maintaining fairness toward employees and other stakeholders while implementing change represents an important practical challenge that deserves further investigation (Camps et al., 2019; Sherf et al., 2019). To more fully understand (and prevent) unfair behavior in change contexts, a more nuanced perspective is necessary.

An important yet historically overlooked fact is that justice enactmentFootnote 1 implies adherence to multiple justice norms (Camps et al., 2019; Graso et al., 2019), whereby different stakeholders, especially in the context of organizational change, may have divergent expectations as to which norms should be central and how these norms are to be enacted. In the context of planned change involving many stakeholders, it is difficult—even impossible—to fulfill all of these (normative) expectations simultaneously, even when managers are highly motivated to act justly. Often, managers may believe that they are enacting fairness, while different stakeholders may perceive and judge the situation differently (Diehl et al., 2021). Fairness is also acknowledged to be a consuming task for managers (Johnson et al., 2014), and managers’ fairness evaluations are colored by their own self-concept (Camps et al., 2019). Moreover, fair behavior is not the only managerial task involved but competes for managers’ motivation and effort to pursue other duties inherent in the managerial role (Huy et al., 2014; Sherf et al., 2019).

In the present research, we investigate how managers tasked with organizational change grapple with irreconcilable demands on how to enact justice in situations we call justice conundrums,Footnote 2 which often involve ethical dilemmas. We specifically ask the following: “How do managers grapple with justice conundrums during organizational change?” We start from the premise that cognitive mechanisms play a key role in how managers grapple with justice conundrums. Specifically, our research is guided by the recent framework of motivated justice cognition (Barclay et al., 2017) and the literature on moral disengagement (Bandura, 1999). Motivated justice cognition (Barclay et al., 2017) refers to the role of motives in justice judgments, meaning that justice is the result of active and motivated information processing. Indeed, research has noted the motivated nature of justice enactment, suggesting that different justice motives and motivational processes (Barclay et al., 2017; Cropanzano et al., 2001; Graso et al., 2019) influence what managers define as fair and drive managers’ fairness enactment. In turn, moral disengagement refers to the cognitive mechanisms that can prevent individuals from perceiving moral cues in specific situations or serve as post hoc rationalizations that allow them to feel comfortable making difficult decisions (Ashforth & Vikas, 2003). These mechanisms may also influence how managers reason about justice conundrums.

To address our research question, we interviewed managers of a globally operating organization who were tasked with planned and large-scale organizational change that impacted structures, people, systems, and culture and ultimately required the managers to make and implement decisions concerning layoffs and replacements. Before the actual change began, all of the participating managers similarly highlighted the importance of justice enactment, although we observed subtle differences in their reasoning about justice. Only 12 months thereafter, they differed markedly in their thinking and reactions. Our analysis reveals three prototypical paths through which the managers grappled with justice conundrums during organizational change and explains how and why each path evolved as it did.

Our study contributes to the literature on justice enactment in the following ways. First, our findings elucidate three types of justice conundrums that managers may encounter when implementing change (the justice intention-action gap, competing justice expectations, and the justice of care vs. managerial-strategic justice), thereby advancing understanding of the complexities and challenges involved in justice enactment. Although researchers have recently acknowledged that justice enactment is far from a straightforward process (Camps et al., 2019; Diehl et al., 2021), our results provide a nuanced understanding of the justice conundrums that managers face. Second, by showing how cognitive mechanisms coalesce to allow managers to soothe their moral concerns, leading to concrete behavioral outcomes as illustrated by the prototypical path we identify, we provide a novel perspective on the motivated cognitive dynamics involved in justice enactment. Third, our study illustrates how and which root differences—specific constellations of justice motives, moral emotions, and circles of moral regard—intertwine to influence managers’ motivated cognitive dynamics. In so doing, we broaden the emerging scholarly discussion on the interplay of (moral) emotions and motivated cognition in justice enactment. We present our findings in an integrative model depicting how managers grapple with justice conundrums during organizational change.

Theoretical Background

The Challenge of Justice Enactment During Organizational Change

A plethora of research has acknowledged that perceptions of justice—of distributions and procedures (see, e.g., Lipponen et al., 2004; Meyer & Altenborg, 2007) or of communication and interpersonal relations (see, e.g., Ellis et al., 2009)—fundamentally impact people’s attitudes and behavior, even more so during organizational change (Meyer & Altenborg, 2007; Monin et al., 2013). A sense of justice thereby legitimates organizational change (Ellis et al., 2009; Monin et al., 2013) and helps people accept it and its implications, whereby injustice elicits the opposite (Meyer & Altenborg, 2007). It thus stands to reason that not only employees but also companies and their managers benefit from justice enactment in the context of organizational change. Justice enactment has been defined as the “extent to which agents (…) adhere to or violate justice rules” (Graso et al., 2019, p. 1). These rules can be classified into four categories (see Cropanzano et al., 2015): distributive justice (the degree to which appropriate allocation norms are followed), procedural justice (whether decisions are made free of bias, accurately, and consistently), informational justice (the perceived adequacy of explanations), and interpersonal justice (the perceived sensitivity of interpersonal interactions and communications).

Managers are typically motivated to enact justice (Graso et al., 2019). Mirroring the motives behind why employees care about organizational justice, Graso et al. (2019) present three managerial motives for justice enactment, namely, instrumental motives of understanding justice enactment as a means to an end, relational motives considering justice to be an important element in relationships, and deontic motives viewing justice as an end in itself. Additionally, managers can be motivated to enact justice to reduce uncertainty (Van den Bos & Lind, 2001). While research has thus acknowledged that managers can have different, potentially coexisting motives for wanting to act fairly, the effect of managers’ motives on how they consider and reason about fairness issues and subsequently implement fairness has received limited attention to date. The question gains importance considering recent work noting that justice may never be fully achieved, as any decision can be experienced as just by some and unjust by others (Camps et al., 2019), and that there can be conflicts between tasks requiring justice considerations versus tasks of a technical nature (Sherf et al., 2019). Especially during organizational change, justice concerns are likely to be heightened, and managers are likely to face numerous and sometimes irreconcilable demands as to what it means to be fair.

Addressing such justice conundrums can be daunting, especially when managers are required to implement choices made by higher management and that they do not support (Richter et al., 2016) and that pose ethical dilemmas. For example, the enactment of interactional justice in the context of “necessary evils” has been shown to be consuming to managers due to the nature of such tasks whereby an individual must knowingly and intentionally cause emotional or physical harm to others for the sake of a greater good (Margolis & Molinsky, 2008). The change management literature in turn shows that managers tasked with implementing change experience considerable stress and discomfort (Folger & Sarlicki, 1998), report higher turnover intentions and display cynicism and withdrawal behaviors (Grunberg et al., 2006). While existing research thus acknowledges the burdens of fairness and change management, the conundrums relating specifically to conflicting demands associated with justice enactment during planned organizational change remain under-examined.

Cognitive Mechanisms and Justice Conundrums During Organizational Change

Importantly, justice norms and judgments are socially constructed, and the selection of justice norms is motivated (Barclay et al., 2017). In other words, managers who wish to act fairly need to choose which fairness norms to prioritize. While previous studies have mainly stressed the additive and positive interaction effects of fulfilling several fairness dimensions at the same time (e.g., the fair process effect, see Van den Bos et al., 1997), the possibility that different justice-related demands can involve competing and even contradictory normative expectations has been largely overlooked until recently. For example, while official communication about a restructuring plan may propagate equity/merit according to performance as a fundamental fairness norm, employees may value equality and emphasize past service, tenure in the organization, and efforts made as a basis for defining what is fair. Thus, justice lies “in the eye of the beholder” (Greenberg et al., 1991), whereby each beholder’s justice conception is influenced by his or her own motive structure and the consequent reasoning about what is fair (Barclay et al., 2017).

Given the subjective and motivated basis of justice judgments, different stakeholders are thus likely to hold divergent, often incompatible views of the (fairness) responsibilities and requirements associated with managing change (e.g., Camps et al., 2019; Diehl et al., 2021) that compel managers to make choices. Consequently, justice enactment represents an effortful activity that entails juggling competing managerial tasks as well as potentially contradictory justice expectations from different stakeholders (Sherf et al., 2019). An investigation into how managers deal with such justice conundrums can broaden our understanding of the motivated reasoning underlying justice enactment involved in juggling various managerial tasks while trying to be fair. Such an understanding is important, as managers can be viewed as norm setters who, through their power advantage, can strongly influence what is considered just in a given context (Fortin & Fellenz, 2008) and propagate new fairness norms in, for example, organizational change contexts (Monin et al., 2013).

Recent theorizing on motivated justice cognition (Barclay et al., 2017) offers a helpful lens for investigating the cognitive processes that managers may experience when dealing with justice conundrums. The set of motives that influence managers’ justice judgments (and enactment intentions) can include making the most accurate assessment possible (the “accuracy motive”) but typically also entails “directional motives” such as a desire to feel good about oneself (Barclay et al., 2017). Managers are likely to be concerned about their reputation and may look for information that confirms their views of themselves as fair managers (Camps et al., 2019). For example, when laying off employees, managers can interpret the equity rule such that the employees in question deserved the outcome, allowing them to think of the layoff as “fair.” As a result of such motivated reasoning and unbeknownst to themselves, managers’ justice judgments are likely to be biased. A visible effect of such biases is that the managers’ justice evaluation differs from that of an independent observer. The degree of such a self-serving bias in motivated fairness reasoning is, however, limited by the so-called illusion of objectivity (Barclay et al., 2017; Kunda, 1990). Even though managers can adapt their fairness judgments according to their motives, this facility is bound to managers’ wish to perceive themselves as objective decision makers (Kunda, 1990). Thus, when the evidence to the contrary and the conflicting perspectives of other parties become overwhelming and can no longer be ignored, managers are likely to recognize the unfairness even if they would prefer not to.

While analyzing the change accounts of our participants, we came to see a related set of motivated reasoning mechanisms as central to understanding managerial fairness reasoning in the context of planned change: Bandura’s (1986) concept of moral disengagement explains how individuals can sidestep their internal moral standards without the distress that would otherwise be caused by such behavior. Although moral disengagement has received much attention in the behavioral ethics literature, it has rarely been considered in the justice enactment literature. Moral disengagement and justice reasoning are, however, closely interlinked, as managers’ moral reasoning is typically based on justice or care considerations (Derry, 1989). Interestingly, a few studies have started to illuminate the antecedents and outcomes of moral disengagement, conceptualizing moral disengagement as an individual’s response to organizational injustice (see Newman et al., 2020 for a review). In turn, the employment of moral disengagement mechanisms can allow individuals—in organizational change contexts, often managers—to reframe their actions such that they can perceive them as justified, if not just. Bandura (1986) differentiates three different categories of cognitive mechanisms that can help managers convince themselves that their actions are morally aligned, even when they represent an injustice to someone else. Specifically, these categories are 1) the cognitive reconstruction of behavior (moral justification, euphemistic labeling, and advantageous comparison), 2) the minimization of one’s role in harmful behavior (the displacement of responsibility, diffusion of responsibility, and disregard or distortion of consequences), and 3) a focus on the target’s unfavorable acts (dehumanization and attribution of blame). For example, managers may minimize their own role in terminating an employee by convincing themselves that they are doing only what is expected of them.

In summary, although the justice literature has noted the cognitive mechanisms involved in the experience and enactment of organizational justice and while injustice has been linked to moral disengagement, we do not yet fully understand how managers handle justice conundrums, especially in organizational change contexts that often harbor many conflicting demands. The literature on both motivated justice cognition and moral disengagement points to the kinds of internal reasoning processes that managers may engage in when confronted with justice conundrums. Therefore, in our research, we examine in depth how managers grapple with justice conundrums during planned organizational change through the lenses of motivated justice cognition and moral disengagement.

Methodology

To address our research question, we chose a person-centric and inductive design to capture “the actual production of meanings and concepts used by social actors in real settings” (Gephart, 2004, p. 457). Our study is based on the principles of grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) by iteratively and inductively constructing theory from data and merging new findings with extant theories (Murphy et al., 2017).

Research Context

The research was conducted in a German branch of a global institution operating in dozens of countries worldwide. Despite the outstanding financial success of the German subsidiary, its parent company introduced a new strategy in 2017 focusing on global alignment. Instead of managing independent country organizations, the company shifted toward a global, centralized management model with centrally designed but locally executed efficiency programs to realize scalability and full organizational alignment worldwide. The new strategy was communicated to employees in townhall meetings and strategy brochures approximately three months before the start of the change, but without yet specifying an exact timeline or explicit implications for the individual. With the stated goal to achieve maximum effectiveness and staff productivity, the strategy involved making fundamental changes in structure, personnel, work processes and systems, and culture. As a result, the number of employees and leadership positions decreased significantly and the remaining positions changed substantially in their tasks, remit, and scope, as did the allocation of authority and division of responsibility among personnel and groups. While the German subsidiary had previously been characterized by long tenure and a hierarchical yet family-like culture, the new strategy was widely perceived as imposed; the cost cuts seen were viewed as unjust; and the pursued market-driven, internally competitive culture was considered countercultural. The envisaged change was thus met with resistance, especially from frontline employees. Consequently, the planned change affected the four major organizational elements (see Huy, 2001): formal structures, work processes, belief systems, and social relations. Managing this change was therefore invariably tied to managing ethical dilemmas as well.

Our first round of interviews (T1) took place before the change process had started; the company had just announced the new strategy, and our interviewees as well as the employees had been informed of the upcoming changes, cost cuts, and planned downsizing. The changes were implemented in the following twelve months, and we conducted the second round of interviews after their implementation (T2).

Participants and Data Collection

In line with the principle of theoretical sampling (Murphy et al., 2017), we purposely selected our interviewees based on their relevant knowledge and experiences and included managers who were directly affected by the changes and tasked with making decisions on layoffs, contract terminations, or placements. We continued interviewing until no new properties of the patterns appeared according to the principle of theoretical saturation (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). During the first wave (T1), we conducted one-to-one semistructured interviews with 33 managers who held department head (8), general manager (4), or team leadership (21) positions. The managers of all levels had to execute strategically difficult decisions and select people to be laid off. Twenty interviewees were male, the average age was 43, and tenure in a managerial position ranged from 13 months to 20 years. The interviews lasted one hour on average and were transcribed. Strict confidentiality was ensured. Depending on the interviewee’s mother tongue, the interviews were held in either English or German. Interviews held in German were subsequently translated into English. For our second round (T2), we interviewed 32 of the managers again. One manager could not participate due to being on maternity leave. By T2, seven managers had left the company, 18 had changed their roles or intended to do so, and seven had stayed in their roles.

The interviews followed an interview guide based on the literature on justice and change management. The preselected themes included the decision contexts and types, justice enactment, and feeling and thinking processes regarding the change. Our pilot interview resulted in minor adjustments to the interview guide (for excepts of the interview guide, see Supplement 2). While the guide allowed for comparisons across interviews, the semistructured design enabled us to remain open to new developments based on the principle of emergence (Murphy et al., 2017). We considered the research process to involve a constant (re)construction of theory whereby data collection and analysis occurred concurrently (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Data Analysis

Following the principle of constant comparison, we switched between collecting data, analyzing the data, and studying the extant literature to ground the emerging constructs and identify possible contributions (Murphy et al., 2017; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). We thereby adopted the twist cone approach (Murphy et al., 2017): On the one hand, we drew on the Gioia, “tabula rasa”, methodology. After primary data collection, we used an open coding system and began our in-depth analysis by labeling the data with codes (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). To identify similarities and differences, we reduced the germane categories to a more manageable number and marked quotes as first-order codes (Gioia et al., 2013), which we then compared with the new findings. While coding, we created an emerging dictionary. Coding first rotated between the authors and was then jointly analyzed to demonstrate dependability (Kreiner, 2016). On the other hand, we complemented the Gioia methodology with a twin slate, “tabula gemini”, approach allowing for the integration of existing theories to meaningfully contribute to the literature in contrast to using grounded theorizing fully disconnected from prior work (Murphy et al., 2017).

Initially, our interviews were mainly guided by the concept of justice enactment, while moral disengagement emerged as a central concept early on in the analysis. After the first coding round, we revisited the literature and refined the codes using vocabulary from the literature (Kreiner, 2016) such as “cognitive reconstruction of behavior.” Throughout the continued data collection and analysis, we further sought expressions used by our interviewees and incorporated these “in vivo codes,” such as “peer reflection,” into our coding structure (Murphy et al., 2017). Furthermore, we conducted member checks and reviewed our results with our interviewees to ensure the trustworthiness of our coding and the credibility of our findings and their interpretation (Kreiner, 2016). While merging the first-order concepts, we developed second-order themes and further distilled these into aggregate dimensions (Gioia et al., 2013).

Findings

The initial analysis of our T1 data led us to conclude that the interviewees uniformly stressed the high importance on fairness, although we also noted differences in the ways in which the interviewees talked about justice. Such differences widened over time, as our later T2 analysis revealed. Based on the emerging patterns, we were able to differentiate between specific types of justice conundrums: the justice intention-action gap, competing justice expectations, and the justice of care vs. managerial-strategic justice. We describe these conundrums below.

Three Types of Justice Conundrums

The Justice Intention-Action Gap

Interestingly, several managers acknowledged at T1 that maintaining fairness would not be an easy task during the change. They described decisions they considered important for justice as being embedded in a wider system that they perceived to be contradictory and ambiguous, including hidden agendas, micropolitics, or conflictive alliances. The managers recognized the existence of justice conundrums that mainly arose from strategically required decisions such as layoffs or relocations, pointing to the contradiction between the company’s expectations of their managerial role versus their personal understanding of their role as moral caretakers of their teams. Thus, their central justice conundrum concerned their inability to enact what they personally regarded as fair.

Some of my colleagues just switched to execution mode and threw their values, their inner convictions, their souls away. I just could not do this. If I cannot act in line with what I think is right, or fair, then this is not the right place for me anymore. (I09).

Competing Justice Expectations

Another group of managers wrestled with the conundrum of different justice expectations and conceptualizations of stakeholders, such as employees, their own managers, the company’s top management, and customers, and the ensuing different demands stemming from these relationships—without picking a clear side themselves. Some also initially mentioned the inability to act on personal beliefs: “Somehow I feel I cannot stay true to myself, there is such a big difference between what I consider right and what others, be it our management, our clients, our employees, or whoever, want me to do (I33).” However, this concern was inextricably linked to the perceived impossibility of simultaneously fulfilling the expectations of different stakeholders: “Doing what our management requests is diametrically opposed to what my team expects, and the same goes the other way round. As a leader, I am horribly torn and caught in the middle (I33).” Consequently, these managers continuously shifted between the perspectives of team members, peers, managers, or organizational demands. Concerned with saving their own and their employees’ jobs, they tried to deal with uncertainty by continuously changing their own prioritization of justice norms depending on the counterpart and context: “You then always try to adjust your behavior, your story, your words depending on the person you are speaking with. Thinking about this…it sounds almost schizophrenic (I07).”

The Justice of Care vs. Managerial-Strategic Justice

The final group of managers primarily perceived justice conundrums with reference to what was demanded of them by the new strategy and what they considered central to the success of the project (e.g., creating economic efficiency) versus caring and almost paternalistic considerations for individual employees (on the ethics of care, see Gilligan, 1982). Even though they initially spoke about their wish to enact fairness toward their employees, this intention was overridden by defining justice from a managerial perspective, such as the efficient and effective implementation of the new strategy. These managers thus perceived a conflict between a managerial-utilitarian justice perspective and employee care concerns, although many also perceived caring as a justice concern. However, the managers in the third group detached justice implementation from the employee care concern. Rather, they aimed to contribute to the survival of the company—and hence to the “greater good”—and explained how their decisions would ultimately ensure the fairest solution for all stakeholders, even if the fairness expectations of individual employees would be sacrificed:

Sometimes you just have to buckle up and do what you’ve got to do. You can’t always meet everyone’s needs. You can’t always be fair toward everyone, and I think it is way cleverer to make sure a company that has been operating for decades will also survive in the future than considering everyone’s needs and fairness concerns (...) even if this means some of our people will probably suffer. (I05)

Prototypical Paths of Justice Enactment During Organizational Change

Interestingly, which of the three justice conundrums a manager focused on was indicative of a host of other differences we identified between managers’ emotions, cognitive strategies, and behaviors, and even indicative of different career decisions at T2. We therefore carefully examined the differences and identified three distinct prototypical paths of grappling with justice conundrums.

To reduce potential interpretative bias, we grouped managers according to the “objective” career decision they had made at T2: One group had decided to leave the organization, a second group decided to change roles within the organization, and the third group remained in their roles.

Managers in the first group primarily perceived justice conundrums based on their inability to act on their intentions. They ultimately upheld their own ideals and moral principles by subsequently leaving the company and thus deliberately maintaining their initial intentions of acting justly “at all costs”; a path we named the leaving path. The second group of managers, who wrestled with the conundrum of competing justice expectations and the ensuing contradictory demands of employees and management, had ended up changing or looking to change their roles within the company at the time of our second interview. We named this path the changing path. The third group of managers perceived conflicts between managerial justice in spearheading the company strategy versus justice of care concerns for individual employees. By focusing on organizational needs, they diverted their attention away from employee concerns, continued business as usual and stayed in their roles—a path we named the staying path.

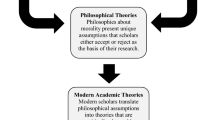

In our further analysis, we compared the participants on the three paths and noted that the initial between-group differences (T1) in justice motives and ways of handling the conundrums as well as the use of moral disengagement grew significantly as the change process unfolded (T2). Once we had developed the full structure for our analysis, we returned to the T1 results for a systematic post hoc analysis. Following grounded theory, we systematically analyzed our data again looking for concepts arising in the same way as the aggregate dimensions. In so doing, we revealed three root differences that appeared to play a key role in the growing divergence of the three paths: justice motives, moral emotions, and the circle of moral regard. These contributed to explaining how the managers conceptualized justice in the first place and what type of conundrum was central to their experiences. This final round of analysis also allowed for a nuanced understanding of how the different concepts and processes were interlinked and thereby enabled us to develop an integrative model describing the three paths in relation to two intertwined processes. In line with the Gioia methodology, we graphically present our data structure as a coding tree (for an excerpt, see Fig. 1; the full coding tree is included as Supplement 1).

Below, we present the three prototypical paths. First, we explain how and why each path evolved as it did. For each path, we structure our findings according to the aggregate concepts (predominant conundrum handling and typical moral disengagement mechanisms) that emerged in our data analysis. Second, we present our findings regarding the three root differences (predominant justice motives, moral emotions, and the circle of moral regard) for the divergence between the three paths identified post hoc.

The Leaving Path

The leaving path was taken by managers whose central justice conundrum was rooted in the gap between their justice intentions and actions.

Conundrum Handling

The managers on the leaving path typically defined their conundrum handling maxim as “acting upon my intentions.” To evaluate what would be fair in the specific situation, they invested in metacognition and reflection—“turning the mirror inwards” (I12). They examined their personal deep-seated beliefs and drivers to determine the right action to take and, consequently, how to enact principled justice under organizational pressures. These managers initially believed that they could “objectively” resolve the conundrums they expected to face by collecting the right information and reflecting carefully on how to comply with organizational expectations and their own principles simultaneously:

It is all about reflecting (…) and finding out who you are and what you stand for. It is like an inner dialog. If you want to be a good leader, you need this meta level. (I09)

Interestingly, at T2, after all the managers on the leaving path had already left the company, they still referred to their initial intentions to invest in such metacognition as a means to clarify what they should do. They recounted that their approach had allowed them to adhere to their internal views on what they regarded as moral. Concretely, these managers reported how they took action for their employees, such as by helping prepare job applications or offering personal support. They thus tried to enact justice in line with their principles and with what they believed was ethical to their subordinates: “You have to take care of your people; they are like your kids, and as a parent, you have to offer help and development opportunities” (I27). After perceiving that the dissonance between internal standards and external requirements could not be bridged, the managers on the leaving path prioritized their personal morals over organizational demands. To refrain from what they considered unfair, they decided to leave the company—their actual justice enactment thus followed the maxim of not compromising their justice beliefs:

You do not fire people only because others say so (…) [and] follow as a soldier. This is not my style. I want to do what I think is right. (I27)

Moral Disengagement

Managers on the leaving path only rarely engaged in moral disengagement mechanisms when determining what to do. Before the change, only one manager considered business reasons for the upcoming transformation when pondering fairness and change, hence engaging in what could be seen as moral justification. The situation was not considerably different in T2. Only two managers seemed to engage in the displacement of responsibility to minimize their own responsibility for their actions before they terminated their contracts. Both managers referred to the in-role obligations of a leader: “This was not me executing, this was a role executing through me.” (I16).

However, the managers on the leaving path described themselves as being embedded in a broader system. They monitored their conduct and its conditions, evaluated it in relation to their moral standards, and regulated their actions considering the anticipated consequences. To avoid self-condemnation, they refrained from behaving in ways that would have violated their moral standards. This process triggered the decision to leave the company, which they perceived as the only way to bring themselves back in line with their moral values:

This is so against my values; I am not here to execute blindly. I want to be here and be allowed to think, to act, in line with what is right. It was horrible to see how much they [my subordinates] suffered. (...) I am here as a human being and not as a worker, and we should treat people as human beings and not as resources. (I12)

In conclusion, the managers on the leaving path predominantly approached conundrums reflectively, driven by a combination of deontic and relational motives, and with an intention to act in line with these motives. They did not compromise but pursued justice as originally conceptualized. They rarely engaged in moral disengagement and felt that many of the difficult decisions required by their employer were unjustifiable. Ultimately, the managers on the leaving path left the company, as they felt they could not remain true to themselves.

The Changing Path

The changing path describes the path of the managers whose experience was focused on the conundrum between competing justice expectations.

Conundrum Handling

Considering their conundrum handling, managers on the changing path framed their maxim as “acting upon others’ justice expectations.” To evaluate what would be fair, they described two intentions: they planned peer reflection to validate their opinions and joint dialogs with subordinates to provide people concerned with the opportunity to express their opinions, corresponding to “giving voice” (see Leventhal, 1980). The following quote illustrates this view: “It is not only about my own perception. I would ask my colleagues for advice and consider different angles, kind of a team decision.” (I02).

However, our analysis of the T2 data suggests that during the actual implementation of the changes, most managers on the changing path—contrary to their plans at T1—did not engage in peer reflection or joint dialog. Instead, they typically followed a three-step process. First, they tried to either withdraw from or avoid making what they feared could be unfair decisions. They showed attempts to deny, hide from, or escape these situations, as one interviewee described:

We are somehow powerless because we are not willing or don’t dare to do something. This sounds like a contradiction; I know this. However, before I do something that is bad, (…) I would rather do nothing. Then, I can also say that it wasn’t me. (I32)

When absolutely needed, they executed the decisions, especially those made on a higher level, and showcased normative behavior to “survive,” which constituted the second step for them. They thereby saw themselves as passive executors who followed orders:

The things I am doing are those that I have to do (…) but this is also not me; this is just the well-behaving man inside of me, following orders. (I32)

As their final step, managers on the changing path typically engaged in morally corrective actions to make amends, including apologizing to, or compensating the victims for their managerial actions to make up for what was unfair from the victim’s perspective. Some of them even engaged in so-called “Robin Hoodism,” i.e., disguised attempts to compensate subordinates for unfair treatment caused by higher management decisions (Cropanzano et al., 2011):

Officially, I executed everything they wanted from me, but in the background, I did a few things differently without letting anyone know. For example, I found a way to honor a few of my employees monetarily. I think the company can pay for this crazy approach. (I14)

Later in the change process, the managers on this path decided to change their roles, with many of them moving to positions without managerial responsibilities. As one manager described,

There was absolutely no discretion in decision-making; this is not the role I want to have as a leader: being the pure executor. Then, I would rather not be in an official leadership role but have an impact on my people and the business—an impact I can shape myself. (I10)

Their actual enactment of justice thus followed an approach of “avoidance of decision-making or selectively fulfilling expectations of different stakeholders.”

Moral Disengagement

When preparing for the changes at T1, several managers on the changing path used moral disengagement mechanisms. Both planned peer reflection and planned dialogs were vehicles of diffusion of responsibility. By initiating dialogs, the managers intended not only to give voice to others but also to share the responsibility for potential harm:

I don’t want to decide myself; we are a strong leadership team. It is not only my business, but the decision made by the group. That is good actually; then, I will not be blamed alone if anything goes wrong. (I02).

As a second anticipatory mechanism to minimize their roles in harmful behavior, some managers engaged in the displacement of responsibility. The responsibility to make and execute difficult decisions on behalf of the company was thereby understood as an in-role duty. By consciously distinguishing between their private and professional roles, the managers framed their actions as stemming from the dictates of top management:

I learned that there are things that I need to do only because I am a leader here. As a private person, I would definitely do some things differently or would never do them. However, as a leader, (…) I have to look at it from both sides. (I33)

At the same time, several managers on the changing path developed moral justification at T1. They argued that the company, as a business enterprise, would be forced to take action to survive:

It is good that we prepare ourselves. Even if this means that we’ll have to think about layoffs, it is still the right thing to do. We need to reinvent ourselves and rethink our staff planning. That is part of a business lifecycle. (I20)

At T2, the managers on the changing path typically acknowledged that their actions had caused harm. In coming to terms with this perceived harm, they again engaged in moral disengagement. For example, they used both displacement and the diffusion of responsibility by referring to the roles and obligations linked to their positions. As stated by one manager (I07), “All decisions that I or others perceived as unfair were only based on the role I had to play.” In line with the T1 statements, the managers on the changing path also reported a diffusion of responsibility at T2 through, for example, the initiation of peer decision-making. The harm could thus be attributed to the decision of a group. They also showed a tendency to attribute the blame to the victim at T2: “We are not a welfare organization. They could have changed themselves deliberately. They had lots of opportunities.” (I04).

To conclude, the managers on the changing path tried to address their conundrums by juggling different justice expectations. To cope with the gaps between the different justice standards, they avoided decision-making or selectively fulfilled expectations while engaging in moral disengagement mechanisms. Despite their moral disengagement efforts, these managers never made peace with the situation and ultimately moved into other positions in the company—typically into ones without responsibility for personnel decisions.

The Staying Path

The managers who at T2 had remained in their role typically perceived a justice conundrum between the justice of care vs. managerial-strategic justice, whereby they prioritized the latter.

Conundrum Handling

Managers on the staying path framed their conundrum handling as “acting upon strategic change directives.” To evaluate what would be fair in the specific situation, they typically planned to engage in peer reflection before the change (T1), which they described as a participatory process through which they would analyze their situation together with peers and jointly select a solution. They sought reconfirmation of their own perceptions, hoping to rely on group decision-making. In doing so, they hoped to receive support from peers in cases of wrong assessment or unwanted reactions:

There is no universal fairness; when I decide for someone, I also decide against someone, at least in regard to distributions, and regardless of whether it was justified or not, the ‘loser’ will not like it. Hence, it is even more important that I double check beforehand to make sure that I loop everyone in (…) [and] that my peers support me. (I08)

Interestingly, our analysis of T2 data shows that the managers on the staying path had taken a proactive approach as the change evolved and even preponed some of their managerial decisions, such as placements. By doing so, they intended to prove their commitment to the company and regain a feeling of autonomy. They hoped that this approach would reduce their feelings of uncertainty and helplessness and establish themselves as actors in charge:

I built a working group to try to design the future. I had to do something and not wait anymore. Just be active, this is what gives me energy. (…) I just dared to make the decisions, with my team in the background. We went through this together; we dared, we conquered. This meant that I could decide myself, that I was not helpless. (I08)

During the T2 interviews, the managers on the staying path continued to describe peer reflection as their key strategy for handling the conundrums they perceived. Their typical motivation, however, was not primarily related to making good decisions but to rallying peer support. What stood out was the assertive style used to describe their behaviors and their focus on efficient change execution, which was recognizable in their patterns of speech:

It is great to work in a company that is ready for the future and can reinvent itself. I am very proud of what we’ve done and look forward to the upcoming years and challenges. I think we are now truly ready to conquer the market. (I23)

Their actual enactment of justice thus prioritized “actively driving, supporting, and engaging in strategic change together with like-minded individuals.”

Moral Disengagement

While focusing on strategy execution and instrumental justice enactment, managers on the staying path engaged in several moral disengagement mechanisms. At T1, many of them had already expressed their intention to diffuse responsibility for the potential consequences of their actions. The inclusion of others in decision-making was seen as protection from potential accusations of injustice: “It is not only my decision. We are one leadership team (…) I am not responsible for this on my own, and if we are supporting it together, I can’t be blamed” (I22). Furthermore, at T1, several managers suggested that employees might deserve negative outcomes, i.e., the allocation of blame to their employees started even before the change implementation:

What I want to emphasize is that it is not the first time that we’ve managed performance. We determined at the beginning of the year what needs to happen for you to do a good job. Hence, if you don’t perform, I will not be able to do anything for you. (I23)

At T2, managers on the staying path typically displayed various attempts to morally disengage from what had happened during the change. First, dehumanization occurred when they portrayed their employees as objects and no longer took into account their employees’ feelings or concerns: “As the saying goes, one rotten apple can spoil a whole box. Or something like that? I had to ensure that these “rotten apples” would not spoil the box” (I05). Managers on this path also frequently attributed blame to the victims of the change (I08): “They get paid for their work. If you don’t deliver, I will not be able to do anything. (…) You either join or leave.” Second, at T2, we observed cognitive reconstruction of behavior, including moral justification, euphemistic labeling, and advantageous comparison. Through moral justification, the managers portrayed their behavior as personally and socially acceptable and worthy:

The sad news is that a few have to, or had to, search for something new. The good news is, many people did not have to do this. Our company is just preparing for the future. Neither the company nor our bosses are guilty for the fact that the market is as it is. (I28)

Several managers also engaged in advantageous comparison by comparing the company’s behavior to the “even worse” behavior of competitors. Based on the contrast principle, harmful acts were made to seem righteous: “With such low performance, other companies would have laid them off way earlier. Maybe we waited too long—maybe it was overdue” (I23). Third, they continued to minimize their roles in harmful behavior in T2. They displaced or diffused responsibility for their actions and distorted the consequences of their actions. Displacement of responsibility occurred by separating private and professional roles whereby the stated professional role consisted of carrying out orders:

Of course, this wasn’t easy, but it is part of my role, and what I did, I did on behalf of the company. (…) Nobody cares about what I feel while doing it. They only care about if I do it, if I execute it, if I keep my promises. (I22)

Finally, through distortion of consequences, managers on the staying path were able to minimize or ignore the effects of their decisions made throughout the change. They denied potential consequences for the employees or reframed the harm as an opportunity. For instance, they claimed that laid-off employees would benefit from the experience:

[…] if you are willing to engage, are motivated, perform well, are a good person, you will find alternatives everywhere, and sometimes, it is also good to change jobs, to make sure you stay flexible. (I23).

In summary, the justice conundrum that managers on the staying path faced centered on conflicts between strategy implementation and individual employee justice concerns. However, these managers tended to quickly resolve this conundrum by prioritizing economic efficiency as a higher-order form of justice to ensure that the work was done. Business reasons validated by peers provided justification for their actions. The managers employed a range of moral disengagement mechanisms that helped them maintain distance from the affected employees and adapt to organizational demands—and stay in their roles.

Explaining the Root Differences in Grappling with Justice Conundrums

Following the above accounts, we were struck by how differently the managers presented their justice intentions and enactment at T2 and how divergently they grappled with the justice conundrums they encountered. We provide additional examples of statements illustrating justice intentions and justice enactment according to the three paths in Supplement 3.

As explained above and following grounded theory, we re-examined our data to search for root differences that could explain these divergent pathways. This second round of analysis revealed important between-group differences in justice motives, moral emotions, and the circle of moral regard already exhibited at T1. We present these findings below.

Justice Motives

Although all interviewees agreed that justice was important, we detected subtle differences in their justice motives at the beginning of the change process. These differences then increased during change implementation. Managers on the leaving path predominantly highlighted two motives. First, most emphasized deontic aspects, pointing to justice being an end: it was their duty to uphold morality and justice. Second, relational motives were stressed in terms of maintaining one’s own standing in the group.

I don't have to set any values for fairness. I mean, this is the deepest human value that we have, the most important, the one that is universally valid. (…) This is not just the task of the leader—this is the most important thing as a human being. (I25).

Among the managers on the changing path, we identified all four justice motives found in the literature. First, several of the managers raised uncertainty-related considerations, stating that fairness judgments constituted effective references for dealing with external uncertainties. Second, managers specifically referred to various stakeholder obligations and expectations that encouraged them to act justly and thus referred to relational motives. Third, they raised deontic concerns, particularly regarding the obligation to treat others justly. Finally, these managers emphasized instrumental motives such as potential economic implications for the company (not for themselves), pointing out the detrimental effects of injustice: “I think when there is no justice, there is no motivation. Working in an unfair environment will demotivate you directly. I have no doubts.” (I24).

Managers on the staying path were mainly driven by instrumental motives and regarded justice as fundamental for the implementation of the change. Most of them promoted organizational economic efficiency, which would ultimately serve personal goals. One manager began reasoning by referring to the deontic motive but continued by emphasizing the instrumental benefit of acting justly:

Being fair and expecting to be treated fairly is deeply human and should be present in any kind of social relationship, no matter the input or output. Especially in our private lives. For our business, however, it is first and foremost a means to ensure effective functioning, effective teamwork, and effective leader-employee relationships. Let's not kid ourselves: Being fair at work primarily serves our business results. (I23)

Unexpectedly, and like the managers on the changing path, they thereby framed justice as a “maintenance factor,” assuming that injustice would lead to performance losses but that justice as such would not lead to gains: “Because if there is justice, you will not notice it (…) but if it is missing, everybody will notice it.” (I22) Thus, the managers on the staying path were largely driven by an instrumental motive to avoid injustice to their organization. Justice toward employees was thus an instrumental duty insofar as it was necessary for effective change implementation.

Moral Emotions

Emotions are understood as adaptive responses to external demands that can propel action, and moral emotions are those “that go beyond the direct interests of the self” (Haidt, 2003, p. 853). Moral emotions can be classified into other-condemning (contempt, anger, and disgust), self-conscious (shame, guilt, pride, and embarrassment), other-suffering (compassion and sympathy), and other-praising (gratitude, awe, and elevation) emotions (Haidt, 2003). Moral emotions influence adherence to or the violation of moral standards and provide a motivational force for doing good and avoiding causing harm (Tangney et al., 2007). We found that managers on the leaving path initially reported other-condemning emotions. They appraised the ongoing events as personally relevant and inconsistent with their values and expressed righteous anger toward responsible others, especially other leaders:

I have not been here for long—but from all that I have heard about this company and the wonderful culture that it had, nothing seems to be there anymore. I am shocked. I am angry that no one listens to us. (I12)

At T2, participants on the leaving path particularly expressed disgust regarding how the organization handled social matters. Contempt was especially expressed in appraisals of others’ lack of values, which thus diminished interactions with individuals who were judged to be less competent in exhibiting the “right” behaviors:

They were trampling down our values. Those that made us unique, that made us great, that made us sustainable. I am not part of this—and I don’t want it to be ever in my life. Yes, we are a business, but we are also human beings, and this is not in line with my values at all. That is pretty much why I quit. (I25)

Managers on the changing path in turn predominantly emphasized self-conscious emotions and fears of demands that would lead to feelings of guilt, especially at T1, and they were afraid of making mistakes. As they saw themselves as responsible for navigating these dynamics, and they expressed feeling drained, exhausted, and nervous: “This is really emotionally draining, stressful, exhausting. (…) I am afraid of making mistakes, today and in the future. (…) I actually feel quite helpless.” (I02) At T2, these managers still expressed a combination of other-oriented sympathy and self-oriented distress. They felt responsible for their subordinates’ unpleasant emotional states and expressed self-conscious feelings of guilt and shame. Shame arose from perceived moral shortcomings; guilt followed the managers’ experiences of self-committed “sins” and promoted proactive pursuits such as the acts of Robin Hoodism illustrated above. The managers voiced self-oriented personal distress accompanied by feelings of powerlessness: “We have a social responsibility for these people. (…) I feel guilty that I could not protect them.” (I07).

Managers on the staying path hardly expressed moral emotions at T1 and only a few expressed them at T2. Some managers voiced fears of losing their job and expressed self-oriented negative emotions; however, there was little evidence of socially oriented fear. Thus, the experienced fear was not linked with moral concerns but rather made them question the competency of their peers, the shortcomings of whom they feared might have repercussions for themselves. At T2, these managers primarily articulated emotions relating to moral disengagement, such as pride about the process or indifference toward the victims. Instead of referring to moral values, the managers on the staying path pointed to new organizational norms and changed milestones as their benchmark for what was right and derived self-worth and pride from their commitment to these: “The whole thing only worked out because a few crazy, like-minded people who wanted to change the world rallied together and just took it on and made it happen.” (I22).

We also noted other-condemning emotions such as contempt for those who were negatively affected by the changes, i.e., the “victims.” Such contempt involved managers looking down on the victims and feeling morally superior and indifferent. Managers on the staying path expressed neither negative emotions in response to potentially being responsible for harm nor empathic feelings toward the targets of difficult decisions: “You have to remind yourself of your role as a paid worker, and if you don’t like your job, you will have to go. It is as easy as that.” (I08).

The Circle of Moral Regard

The circle of moral regard is defined as a group of others whose needs a person shows concern for; a manager’s circle of moral regard indicates how he or she views the system and its different parts (Reed II and Aquino 2003). It can be limited to a narrow set of others, such as one’s family, or it can be large enough to include outgroups. Our analyses suggest that the differences in moral regard among the three paths were already pronounced at T1, even before the changes had begun. As outlined above, managers on the leaving path expressed deontic and relational justice motives and drew on their own moral standards without reference to the company’s economic concerns. Their moral reasoning was characterized by a large, transcendent circle of regard, including considerations for interdependent complexity of the organizational system:

An organization is full of life and not like a big machine. You cannot simply replace one screw and expect that the others are working as before. (...) There are people, there are groups, there is a culture, and all of this is very complex. (I12)

In contrast, managers on the changing path switched between different circles of moral regard depending on the stakeholders they saw as central in a specific situation. The consideration of diverse, often contradictory, interests of different groups led to coexisting standards of behavior that were not always reconcilable. The managers came to accept such contradictions as normal and switched between serving either the company or their employees:

Leadership and the relationship between leader and employee is almost like a marriage. Yet, you are also somehow married to your company; you should share the same values with your employer, right? (I03)

As mentioned, we identified all four justice motives among the managers on the changing path. Our analysis suggests that these different motives go hand in hand with their stakeholder-oriented circle of moral regard. For example, when considering the perspective of the organization, these managers focused on instrumental justice motives. When taking the perspectives of the employees and their leadership roles into account, they applied relational justice motives.

Conversely, the managers on the staying path displayed a narrower circle of moral regard, mainly focusing on the fulfillment of their own needs and viewing the company as an economic entity. However, these managers did not necessarily make their decisions due to an absence of moral consideration but rather out of a strongly felt obligation to act on behalf of the company and thereby to save their own (and potentially others’) jobs. Such a narrow circle of moral regard also allowed them to largely disregard the potential needs of other stakeholders (especially of employees), where such consideration might have led to psychological discomfort.

Integrative Model of Grappling with Justice Conundrums

What emerges from our findings is an integrative model of grappling with justice conundrums (Fig. 2) depicting three prototypical paths (see Table 1).

Specifically, the model presents the grappling with justice conundrums as a process comprised of two distinct yet interlinked parts—justice intentions and justice enactment. It illustrates how justice conundrums take shape and how managers’ responses to them evolve along different paths. In so doing, the model sheds light on why managers working in the same context—who all believe in the importance of justice—can differ markedly in their reasoning about organizational justice and react differently over time.

Justice Intentions

Our model begins with justice intentions, which captures the interactive importance of three main differences (Fig. 2): justice motives, moral emotions, and the circle of moral regard. At first, managers may (consciously or not) consider questions such as who deserves consideration in terms of justice. Our results show how the answer to such questions is linked with specific moral emotional experiences that go hand in hand with different circles of moral regard and justice motives. Indeed, it seems that the three factors are not orthogonal but tend to mutually influence each other. Therefore, we present them graphically in a “loop.” This mutual influence results in typical constellations, which we discuss in the following.

First, the leaving path is characterized by a broad circle of moral regard and a dominant deontic justice motive—the desire to uphold justice in a transcendent way. Other-condemning emotions such as righteous anger are also typically common when the actions of others are seen as morally repulsive. The changing path stands out through a coexistence of all four justice motives with a predominance of the relational justice motive and a stakeholder-oriented circle of regard, which changes its focus depending on the situation, people involved, and context. Managers on this path tend to experience self-conscious moral emotions, such as guilt or shame, elicited when some aspect of the self is scrutinized and evaluated with respect to moral standards (Tangney et al., 2007) and can lead to corrective actions such as Robin Hoodism. The staying path, in turn, is marked by instrumental justice motives and a self-centered circle of regard in concert with a sense of duty primarily toward the organization and a lack of moral emotions. These conceptualizations then affect how justice enactment unfolds.

Justice Enactment

In the first loop, managers formed an intention for how to enact justice in the upcoming change. As both the recent literature (Barclay et al., 2017) and our findings suggest, such intentions are motivated. Table 1 illustrates how each constellation of factors thus forms what we call a motivated justice intention that represents the transition into the second process—justice enactment—and at the same time links both processes. This is when justice intentions meet organizational reality, and thus competing expectations, different norm conceptualizations, difficulties in acting upon the intentions, or various justice considerations that confront each other. Motivated justice intentions can be influenced by moral disengagement mechanisms (e.g., by allowing ex ante rationalizations of acts that would serve specific chosen motives), and such mechanisms play an important role when managers realize that they may not be able to enact justice in line with their initial intentions. Moral disengagement thus helps reduce the perceived dissonance between intentions to enact justice and organizational reality and cope with the conundrums faced. Importantly, while each constellation of justice motives, moral emotions, and circle of moral regard predisposed managers before the change to anticipate a specific justice conundrum, only in this second loop was the conundrum truly experienced.

The managers on the leaving path hardly engaged in moral disengagement mechanisms. Therefore, they could not reconcile the conundrum of experiencing a gap between their understanding of what justice means versus their room for maneuvers in justice enactment. They extricated themselves from the conflict-ridden justice enactment process by leaving the company. Conversely, the managers on the adapting path typically exhibited an “organizational reality compliant” justice intention, which was facilitated by the fact that, from the beginning, they had prioritized a managerial-strategic conceptualization of justice. To address the perceived conflicts between the managerial justice perspective and justice of care concerns, they prioritized the former and engaged in the most moral disengagement techniques, facilitating what they considered as justice enactment. Together, these mental strategies allowed them to stay relatively comfortably within their managerial roles from T1 onward.

Finally, the managers on the changing path seemed to continue to shift within and between the two loops. Confronted with the conundrum of competing justice expectations and conceptualizations of different stakeholders, they appeared to be torn between the different demands of these different perspectives, represented by changing circles of moral regard. Simultaneously, they held manifold and often contradictory justice motives. Consequently, they adjusted their conceptualization of justice depending on the stakeholder they were dealing with and disengaged morally from the situation, yet not to their full satisfaction. However, the prolonged shifting within and between the processes tended to exhaust them over time, and they withdrew from their roles, ultimately changing their jobs or intending to change their jobs.

Discussion

The challenges involved in knowing “what is fair” and “being fair” have recently been highlighted in the justice enactment literature (Barclay et al., 2017; Diehl et al., 2021; Sherf et al., 2019). Our research shows how managers involved in organizational change reasoned about justice differently, experienced different types of conundrums, and grappled with these conundrums with increasing divergence, culminating in distinct career decisions. Below we discuss our distinct contributions to the burgeoning justice enactment literature.

Theoretical Contributions

Justice Conundrums

Recent research has recognized that fair behavior often clashes with non-justice duties or more technical aspects of work (e.g., Sherf et al., 2019) and that different stakeholders hold different justice expectations that cannot be simultaneously pleased (Camps et al., 2019), especially during organizational change. Our study extends this line of research by elucidating three types of justice conundrums that illustrate how managers try to balance and prioritize multiple, oftentimes competing justice motives and the corresponding responsibilities they perceive for themselves.

First, there is a gap between justice intentions versus actions and the opportunity to act in line with initial intentions, a challenge emphasized by managers on the leaving path. The managers who highlighted this conundrum prioritized their deeply held justice principles over organizational justice enactment directives. Therefore, when they perceived that they were not able to act on their justice intentions, they left the company. The second type of justice conundrum arises from the competing justice expectations of different stakeholders, resulting in managers having to weigh the importance of each expectation and choose among them. This struggle was expressed most strongly by managers on the changing path, who could not prioritize among the different justice perceptions and finally decided to change their roles and give up their managerial responsibilities. The third type of conundrum stems from the difficulty in prioritizing one’s focus and resources between managerial justice required by a strategic change and employee-focused justice concerns of care. This conundrum was typically voiced by managers on the adapting path who stayed in their roles after the change was implemented. They mainly dealt with the conundrum by choosing the managerial-utilitarian conceptualization of justice over employee care concerns.

Revealing these distinct facets of the justice-related struggles and trade-offs managers face when tasked with change sheds light on justice enactment in the context of a puzzling organizational reality. As Burnes (2011) pointed out, the change management literature has brought forward many prescriptive models for how to manage change (e.g., Kanter et al., 1992; Pugh, 1993). It seems, however, that these models have paid little attention to the precise mechanisms of why different groups within an organization may have radically different reactions to the same organizational change, even when they seemingly share the same type of position and interest. The present study suggests that a more detailed understanding of the conundrums that change managers face, and focus on, when enacting justice can also elucidate theories of change management and may especially help shed more light on the crucial role of line managers and middle managers in change processes.

Motivated Cognitive Dynamics of Justice Enactment

Managers, as all individuals, are subjective, active, and motivated processors of information (Barclay et al., 2017; Kunda, 1990). As fairness lies “in the eye of the beholder” (Greenberg et al., 1991), justice enactment can—from the manager’s perspective—mean compliance with justice standards set and prioritized by oneself. These standards can be adapted as the situation (and one’s motivation) evolves—a largely overlooked angle in the literature. Furthermore, our study shows that in managers’ minds, justice enactment is not limited to deliberate actions or the planning of these actions but can also include an intentional effort to not act in specific ways. Such decisions and efforts are likely to remain unnoticed by justice recipients and other evaluators. Our study illustrates that even when managers wish to act justly during organizational change, they typically encounter justice conundrums and are confronted with their own limited latitude. While some cope with cognitive dissonance through moral disengagement mechanisms, the very presence of moral disengagement mechanisms even before the actual change happens renders support for the notion that these managers cannot be considered “amoral” but rather decide to prioritize differently when engaging with moral questions.

The integration of the moral disengagement and justice enactment literature extends the emerging motivated cognition perspective to justice (Barclay et al., 2017). Our findings suggest that when managers are confronted with the recognition that their decisions or acts are perceived as unfair by another stakeholder, two distinct cognitive effects coalesce: motivated cognition and moral disengagement. These cognitive mechanisms extend the current theorizing on justice enactment and help explain why actors who believe in the importance of justice may sometimes commit acts that are perceived as unjust by others, while feeling they are acting justly. Moral disengagement mechanisms typically come into play after managers have directly witnessed their employees experience unfairness and once the limits of the illusion of objectivity in their motivated reasoning are reached. Thus, motivated cognition, and when needed, moral disengagement, allow managers to justify their prioritization and interpretation of justice norms and to feel better about what may be seen as a violation of justice norms by other members of the organization. In this way, moral disengagement can even serve to alleviate managers’ concerns in cases where the “illusion of objectivity” does not allow them to perceive an action as fair.

Motivated Justice Intentions

Our study reveals that the foundation of the differences among managers’ justice conundrums and the accompanying paths of grappling with them may lie in a concept we call motivated justice intentions, ensuing from a specific combination of justice motives, moral emotions, and the circle of moral regard. Our study emphasizes that individuals differ in the emergence and experience of moral emotions (Haidt, 2003) and enriches the justice enactment literature by suggesting strong interconnections among justice motives, moral emotions, and the circle of moral regard. The managers’ circle of moral regard (or scope of justice, Opotow, 2005) sheds light on the following question: To whom are managers ultimately responsible? Such considerations go hand in hand with justice motives, such as whether justice is seen as a virtue in itself (deontic motive) or a means for improving outcomes (instrumental motive) and how they feel about their task at hand. The specific configuration of these three intertwined concepts then carries forward to influence how managers perceive their reality, and which conundrums they face and how to handle them.

Thus, justice enactment is not only a straightforward matter of converting motives into actions and following specific norms but also one of serving those who belong to one’s circle of moral regard, guided by emotions, adjusting via cognitive mechanisms and weighing different motives relevant to the managerial role. Our study thus offers the novel insight that the specific configuration of a manager’s motivated justice intentions alters subsequent behaviors and explains how managers grapple with justice conundrums.

Limitations and Future Research

While we recognize the limitations of our study, they allow us to offer promising themes for future research. First, the generalizability of our findings may be limited given that our research was conducted in one company and sector with their specific issues. Furthermore, while the prototypical paths identified capture the ways in which the different groups of managers dealt with the presented conundrums, we also acknowledge that not all managers neatly fit into the categories that emerged from our analysis. For example, not all managers who decided to stay in their roles engaged in all moral disengagement mechanisms identified by the literature. Future studies might thus build a richer typology of justice conundrums and paths by examining larger samples across different change contexts and across different industries and cultures. Second, our findings highlight the importance of understanding the short- and long-term temporal dynamics of justice enactment (Desjardins & Fortin, 2020). While we interviewed our participants on two occasions with a one-year gap between, future research conducted on shorter time intervals could tap into different cognitive and emotional processes to determine how the configurations of justice motives, moral emotions, and the circle of moral regard develop. When considering a longer timescale, the conundrums associated with justice enactment may impact managers’ long-term career trajectory. Thus, the conceptualization of justice between managers but also among individual managers over time merits further research.

Practical Implications